California Race War

Raymond Wolters, The Occidental Quarterly, Spring 2008

Driven Out: The Forgotten War against Chinese Americans, Jean Pfaelzer New York: Random House, 2007.

The United States has had a good deal of experience with what can be called “ethnic cleansing.” Native Indians were forced to give way to Caucasians. And, as Jean Pfaelzer reminds us in Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans, there were significant expulsions of Chinese from the states of the Pacific Coast.

Thanks to the work of other scholars, many informed Americans already have some familiarity with this subject. But Jean Pfaelzer, a Professor of English at the University of Delaware, has written the most detailed and comprehensive account of the expulsions of the Chinese. Thanks to her impressive research, we now have an encyclopedic catalogue of roundups and evictions. This essay will discuss the expulsions and the eventual restriction of Chinese immigration, and will also discuss Professor Pfaelzer’s explanations and those of some other historians. These explanations differ from the views of the editors and contributors at The Occidental Quarterly.

The Origins of Chinese Immigration

The earliest surge in Chinese immigration came in 1850, shortly after gold was discovered in California. At that time many peasants and workers in the vicinity of Hong Kong and Canton were living in desperate conditions. Shipmasters consequently had little difficulty persuading Chinese men to sail for “Gold Mountain,” as California came to be known. Chinese families sold fields or fishing boats to cover the expense of transportation and, according to Professor Pfaelzer, many young men embarked with dreams of becoming citizens of the United States. Professor Pfaelzer uses the phrase “Chinese Americans” in her subtitle, and she insists, “most Chinese who came to work in the mines, and, later, on the railroad or in the orchards, came voluntarily.” She acknowledges, however, that some of the Chinese immi-grants “bore a heavy debt to labor contractors [and] shipping companies.” To cover the cost of transportation, many of the Chinese immi-grants agreed to work as indentured servants.

Professor Pfaelzer’s emphasis on the Chinese desire to assimilate differs from a theme that Berkeley historian Gunther Barth developed in his book of 1964, Bitter Fruit. According to Professor Barth, most young Chinese emigrants wished to escape from the depredations of Chinese warlords and British imperialists, and also hoped to acquire wealth in a foreign land. But they were merely “sojourners” while liv-ing abroad. They dreamed of making money and then returning to China with their savings “for a life of ease, surrounded and honored by the families which their toil had sustained.” UCLA historian Alexander Saxton similarly maintained that most Chinese workers in America “viewed their journey as a round trip. [They] were birds of passage, ‘sojourners’ in America, whose conscious intent was to stay a little while, save a little money, and return to the nest.”Most of the Chinese immigrants came to the United States by way of what was called a “credit ticket” system. Under it, workers were advanced the cost of transportation in return for a short term of indentured service. The plan, as described by Professor Barth, was for the immigrant to stay in America . . .

until he was fifty or sixty, when he would return to his native village, a wealthy and respected man, to enjoy the rest of his life venerated by the large family which he had kept intact with his earnings and savings during the long years overseas. . . . During the long absence . . . he hoped to visit [China] several times, to marry the girl chosen by his family and to beget children. His wife would remain in the native village and bring up his offspring. . . . Overseas he would maintain a very low living standard and save the larger part of his income for his family which depended on his remittances. The long years in the strange world would not break the emigrant’s emotional ties with his family. The tablets of his ancestors in the clan hall and his children in the family home, the veneration of his parents, and the desire to live lei-surely in China would maintain his loyalty during his adventurous years [abroad].

Despite the desire to return to China, most Chinese workers remained in America. “For many Chinese migrants, America turned out to be not ‘Gold Mountain’ but a mountain of debt.” As six Chinese companies explained in an address to Congress, wages were so low that most Chinese workers were “compelled to labor and live in poverty, quite unable to return to their native land.” Although they had originally considered themselves sojourners, “from the very beginning . . . Chinese migrants showed signs of settlement.”

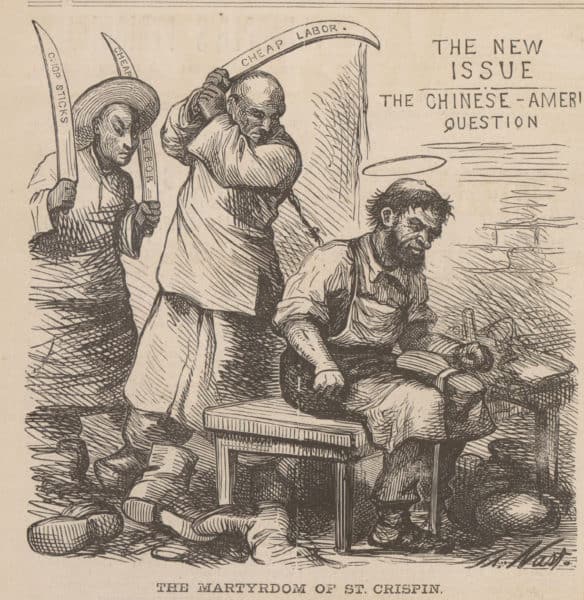

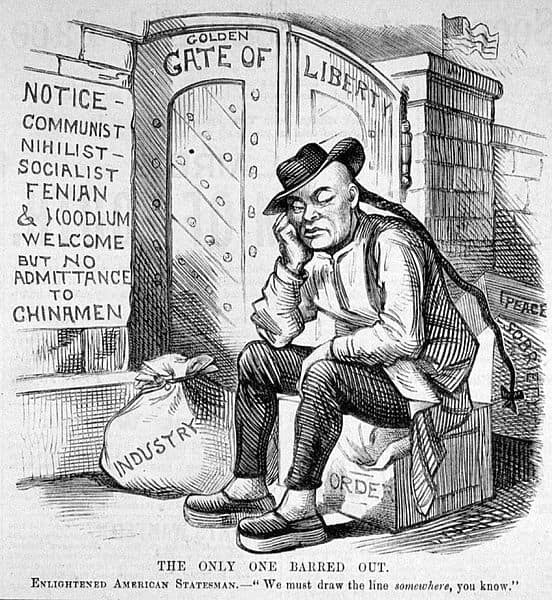

Martyrdom of St. Crispin by Thomas Nast. Harper’s Weekly 16 July, 1870. Source: UDel / Walfred

California’s Caucasian miners took a dim view of this. They regarded Chinese miners as unwelcome competitors, “coolies brought here by rich mandarins or merchants to work for little more than a bear [sic] subsistence.” At first the white miners tried to legislate the Chinese out of California — with one law of 1852 requiring each foreign miner to pay $3 a month for the right to mine, with the amount increased to $4 in 1853 and $6 in 1855, with a $2 increase each year thereafter. Nevertheless, Chinese miners continued to come, and the Daily Alta Californian complained that “every gulch and ravine” was filled with so many Chinese miners that “an American emigrant can hardly find room to pitch his tent.” According to Professor Pfaelzer, “the Foreign Miners’ Tax had cut the Chinese population by the thousands, but after a few years new arrivals equaled and quickly doubled the number of those who departed.” During the early 1850s, “thou-sands of Chinese remained in the mother lode and thousands more continued to find their way.”

Eventually, white miners resorted to direct action. One precipitating factor was a proposal that California state senator George B. Tingley introduced in 1852. This proposal would have allowed laborers who were desperate to leave China to sell their services to contractors at fixed wages for a period of up to ten years. In response, a miners’ convention condemned “the predisposition on the part of merchants, commercial men, etc. to flood the state with Asiatics [and] fasten a system of peonage on our social organization.” Going beyond rhetoric, white miners in Mariposa County, near the western entrance to Yosemite Valley, posted a notice that all Chinese should leave “within ten days” and that “any failing to comply shall be subjected to thirty-nine lashes, and moved by force of arms.” When some Chinese disregarded the notice, they were rounded up and beaten, and their cabins were torched. The same pattern was repeated in other counties. In 1853 three thousand Chinese men were mining the river beds and creeks in Shasta County alone. By the end of the decade, after several battles known collectively as “the Shasta wars,” only 160 remained. By 1860 the Chinese era of the gold rush had come to an end.

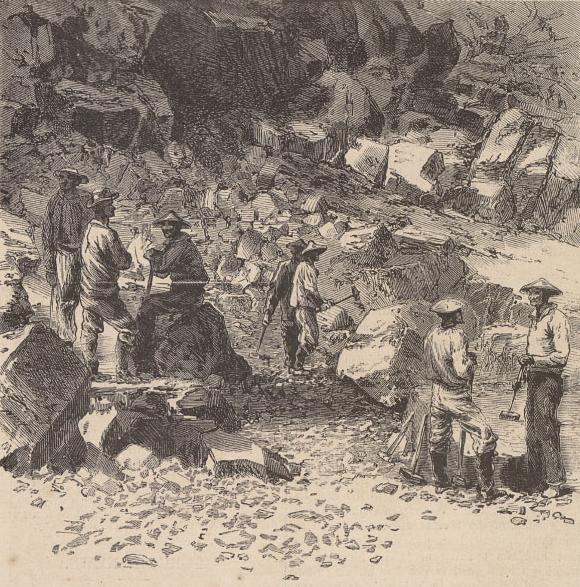

The displaced Chinese miners then moved into other occupations. Some made their way to lumber camps, others to farms, ranches, and orchards, and still others plied various trades in cities and towns along the Pacific Coast. When the construction of the transcontinental rail-road got underway in the 1860s, there was also a spike in the demand for railroad workers. Central Pacific Railroad magnate Charles Crocker then recruited thousands of workers from South China — enough to make up a 10,000 man industrial army that was called “The Army of Canton in the High Sierra.” Central Pacific president Leland Stanford said it would have been impossible to complete the western portion of the transcontinental railroad without these Chinese workers, and Professor Saxton calculated that “four men in every five hired by the Central Pacific were Chinese.” By the 1870s, about 25 percent of all male workers in California were Chinese.10 The Chinese workers saved the railroad a great deal of money since “the going rate for white unskilled labor had been thirty dollars a month plus board and lodging. Chinese received the same sum in cash, but fed and housed themselves.”

The employment of Chinese workers was arguably at odds with the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which declared that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude” should exist within the United States. Scholars have continued to debate whether the Chinese workers were “slaves,” “coolies,” or merely “indentured servants.” Professor Pfaelzer says that most Chinese workers chose their lot freely, but most labor historians have echoed Professor Saxton’s judgment that the system “was in fact very similar to slavery.” Most Chinese workers remained under bond for their passage and other debts they owed to Chinese merchants living in California. The shipping companies and merchants then provided the workers to the railroad in gangs.

“Central Pacific Railroad–Chinese Laborers at Work” from Harper’s Weekly, Vol. XI, No. 571, p. 772.

Most of the Chinese railroad workers dispersed after the transcontinental road was completed in 1869. Nevertheless, anger mounted against those who continued to work for the railroads. This was evident at an incident that occurred at Rock Springs, a Union Pacific facility in Wyoming. In 1885, 331 Chinese and 150 whites were em-ployed at Rock Springs. By then the wages apparently were identical, but there were hard feelings when the Chinese refused to join in a strike. White workers then marched on the Chinese quarters, armed with shotguns and chanting the slogan, “The Chinese Must Go.” “After firing a volley into the air, [the whites] ordered the Chinese to leave. The Chinese fled, pursued by white [workers], who now fired directly at them. The Chinese quarters were set ablaze . . .” “The next day when the bodies were picked out of the ashes and dragged in from the surrounding sagebrush, the official count came to twenty-eight Chinese killed, fifteen wounded.”

A Less-Than Model Minority

The incident at Rock Springs and other similar but less lethal events that Professor Pfaelzer recounts were not simply a product of industrial conflict and strained labor relations. Concerns over morality also made similar points, played a part. Whites said the Chinese miners were addicted to gam-bling and opium and lived in conditions that threatened the health of others nearby. According to the San Francisco Herald, groups of twenty or thirty Chinese miners lived together in “cabins so small that one . . . would not be of sufficient size to allow a couple of Americans to breathe in it. Chinamen, stools, tables, cooking utensils, bunks, etc., all huddled up together in indiscriminate confusion, and enwreathed with dense smoke, present a spectacle which is . . . suggestive of any-thing but health and comfort.”

Professor Ivan Light, a sociologist at UCLA, has noted that Chinese Americans eventually came to enjoy “the friendly popular image” of a model minority, “exemplars of cleanliness, sobriety, and peaceful-ness.” But it was not always so. Between 1865 and 1920, “whore-houses, gambling joints, and opium dens . . . flourished in major American Chinatowns.” According to Professor Light, this was not simply the distorted and exaggerated testimony of anti-Chinese bigots. The evidence was “overwhelming that social conditions [among the Chinese] were . . . deplorable.” In 1870 health inspectors in San Francisco reported that “rooms which would be considered close quarters for a single white man were occupied by shelves a foot and a half wide, placed one above another on all sides of the room, and on these from twenty to forty Chinamen are stowed away to sleep.” The health officials said they held their noses as they “groped their way with candle in hand” inspecting “the dark and dingy garrets and cel-lars, steaming with air breathed over and over, and filled with the fumes of opium.” According to one report, in 1885 there were 14,552 bunks for single men in one ten-block stretch of San Francisco’s Chinatown.

These conditions appalled many observers. One such was Samuel Gompers, the president of the American Federation of Labor. He never forgot the sights he had seen when some of his friends took him for a tour. “It was an awful experience. I had read Dante’s Inferno, but Chinatown seemed to me a greater horror with its reeking smells, the human wrecks, gambling, and mad licentiousness.” In his 1901 presidential address to the AFL, Gompers declared, “every incoming coolie means . . . so much more vice and immorality injected into our social life.”

Professor Light relates the conditions in the Chinese districts to the fact that the immigrants were overwhelmingly “men in the prime of life.” Most were either single sojourners or married men who had left their wives and families in China. Between 1850 and 1880, there were about twelve Chinese men in America for every Chinese woman, with the disproportion increasing to more than 20:1 in the 1880s and 1890s. In San Francisco one government report described the Chinese quarters as “the filthiest places that could be imagined . . . with hundreds of Chinamen . . . crowded to excess,” cooking on the floor, without stoves and chimneys, “in a manner similar to our savage Indians.” Another government report characterized Chinatown as “the rankest outgrowth of human degradation . . . upon this continent.” The investigators feared that the conditions would eventually lead to an epidemic of cholera, and ordinary Californians came to regard the filth and stench of Chinatown “as inseparable from the nature of its inhabitants.”

Samuel Gompers

The situation was even worse for female immigrants from China. According to Tomas Almaguer, a professor of ethnic studies at San Francisco State University, prostitutes made up 85 percent of the fe-male Chinese in San Francisco in 1860. Sucheng Chan, a professor of Asian American studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, has written that during the decade of the 1860s “fully one-third of the gainfully employed Chinese in [San Francisco] were engaged in providing recreational vice — an unfortunate fact which gave rise to strong negative images of the Chinese.” “Opium smoking was commonplace in Chinatowns,” Professor Light has written, and “white patronage was a significant part of Chinatown’s total opium business.” In addition, white men “apparently felt free to engage [Chinese] ‘sing-song’ girls in aberrant sexual practices which they would have blushed even to mention to the most jaded of white har-lots.”

To make things worse, many Chinese women were held against their will. “Despite the abolition of slavery,” Professor Pfaelzer has noted, “the sale of humans endured in the West.” Professor Pfaelzer’s account deserves to be quoted at length:

Most Chinese prostitutes in the American West had been in bondage since a young age, sometimes since infancy. Many were “go-away girls,” female babies who were abandoned [or] sold . . . A newborn baby girl could be disposed of — deposited in a bas-ket where anyone wishing to own a female child was at liberty to remove her and do with her as he liked. Most Chinese prostitutes came through San Francisco, imported by criminal societies that by 1860 had taken control of the trade. Brokers in China procured the girls, kidnapping them off the streets or purchasing them from destitute families and selling them at great profit in San Francisco. The enslaved children were brought to the United States by large syndicates that owned as many as eight hundred girls . . . Wealthy Chinese individuals, male and female, paid about eighty dollars to a broker for a girl in China, or between four hundred and a thousand dollars if they bought her in an organized slave sale in San Francisco, often in a designated cellar in Chinatown. . . . To get around the Thirteenth Amendment and laws banning indentured contracts, buyers often paid the purchase money to the girl, who then turned it over to her new owner as she marked or signed a contract indenturing herself. In a typical contract a girl promised to “prostitute my body for the term of ___ years. If, in that time, I am sick one day, two weeks shall be added to my time; and if more than one day, my term of prostitution shall continue an additional month. But if I run away from the custody of my keeper, then I am to be held as a slave for life.”

Resistance to Chinese Immigration

Beginning in the 1850s, white Californians enacted various policies, ordinances, and laws to dissuade the Chinese from coming. Mention has already been made of the foreign miners’ tax. Another law established eight hours as a standard workday, a policy that Professor Pfaelzer describes as “an attack on the Chinese, who worked long hours in laundries and in shoe and cigar factories.” Among other measures there were “sidewalk ordinances,” which banned the Chinese from carrying vegetables and laundry in baskets hanging from shoulder poles; and “cubic air ordinances” aimed at Chinese rooming houses where workers slept by turn in the same bunks. These ordinances required each adult to have at least five hundred cubic feet of living space or pay a fine ranging from ten to five hundred dollars.

Despite these and other ordinances, the Chinese kept coming to America, and conditions continued to fester. In these circumstances, only a spark was required to set off a conflagration. One of the worst instances of anti-Chinese violence occurred in Los Angeles on October 24, 1871. The precipitating incident had occurred two days earlier when brokers for rival Chinese syndicates were involved in a shoot-out over a runaway Chinese prostitute. When another Chinese shoot-out occurred on October 24, the police chief deputized a group of white men with orders to shoot any Chinese who left their houses. In the ensuing clashes, nineteen Chinese were killed while one white man also lost his life. Eventually, eight white men were convicted of manslaughter but later were released because of a legal technicality.

In response to the melee in Los Angeles, and other similar but not-so-deadly incidents, the California state senate established a committee to take testimony on the effects of Chinese immigration. The investigation led to the publication of a lengthy report in 1876, but, as California historian Hubert Howe Bancroft noted, “practically the subject remained where it had been.” The powers that ruled were not willing to restrict Chinese immigration. Industrialists and ranchers insisted that Chinese workers filled a real economic need in the state. They said that the Chinese were “doing the work which white men refused to do.” Some well-to-do white women also recognized that they owed their comfortable lifestyle — “their new leisure, their freedom to travel east to visit friends and family, and their time for church and artistic clubs” — to the availability of “inexpensive Chinese servants.”

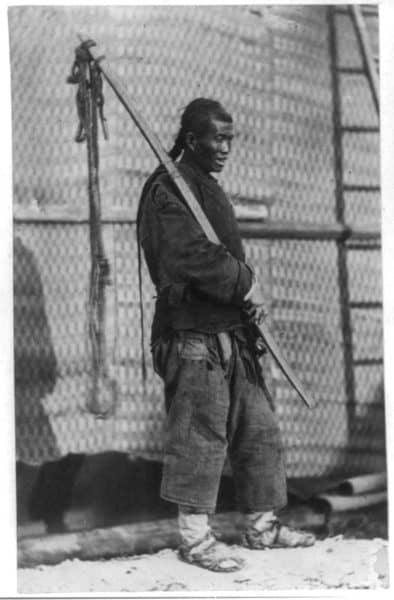

A Chinese “coolie.” (Credit Image: John Thomson / The Library of Congress)

Most employers regarded the Chinese workers favorably. The Chinese, after all, provided the cheap and efficient labor that was needed in agriculture, manufacturing, and large construction projects. Nevertheless, as Elmer Sandmeyer noted in his doctoral dissertation at the University of Illinois, Caucasian workers in California “were almost unanimous in the opinion that the Chinese were highly detrimental to the best interests of the state.” Economist Henry George spoke for these workers when he wrote that “coolieism” was as great a danger to free labor as slavery had once been. In a letter to the New York Tribune, George insisted that Chinese immigration was making “the rich richer and the poor poorer.” It was making “nabobs and princes of capitalists and crush[ing] our working classes into the dust.” It would “substitute (if it goes far enough) a population of serfs and their masters for that population of intelligent freemen who are our glory and strength.”

Before long, less refined men were making similar points. The most prominent was Denis Kearney, an Irish immigrant who had achieved middling prosperity as the owner of a trucking business in San Francisco. Henry George once described Kearney as “moderate in every-thing except speech.” In 1877 Kearney skyrocketed to fame with impassioned speeches that always ended with the words, “And whatever happens, the Chinese must go.” Kearney also condemned the magnates who employed the Chinese. He held meetings on vacant lots across from city hall and outside the Nob Hill mansions of such eminences as Charles Crocker, Leland Stanford, and Mark Hopkins. “When the Chinese question is settled,” Kearney declaimed, “we can discuss whether it would be better to shoot or cut the capitalists to pieces.” If the rail-road owners did not dismiss their Chinese employees, Kearney warned, they should “remember Judge Lynch.” “I will give the Central Pacific just three months to discharge their Chinamen, and if that is not done Stanford and his crowd will have to take the consequences.” “The dignity of labor must be sustained, even if we have to kill every wretch that opposes it.”

Kearney was accused of incitement to riot, but he was not convicted, and the charges probably enhanced Kearney’s reputation with rank-and-file white workers. Building on that popularity, Kearney organized the Workingman’s Party of California. That party, in turn, persuaded Californians to hold a new state constitutional convention. The new constitution then provided that no state, county, municipality, or corporation could employ Chinese workers. The English Lord, James Bryce, who was in California at the time, observed that the “monied men” of the state “vehemently opposed” this Constitution of 1879, but the state’s voters approved the document by a vote of 78,959 to 67,134. Fortunately, Lord Bryce wrote, “no great harm was done” because the courts “pruned and trimmed” the document to conform to the requirements of equal protection and due process. “More mis-chief would have been done but for the existence of the Federal Constitution. It imposed a certain check on the Convention, who felt the absurdity of trying to legislate right in the teeth of an overruling instrument. [The US Constitution] has been the means of upsetting some of the clauses of the [California] Constitution of 1879.” Agitation against the Chinese continued despite the courts, as white Californians demanded that the national Congress restrict further immigration from China. In 1876 Congress established a Joint Special Committee that conducted eighteen days of hearings in San Francisco and Sacramento, heard 129 witnesses, and collected 1,200 pages of testimony and statistics. The final report of the investigating committee reiterated the case against the Chinese immigrants. The committee also warned of the possibility of an uprising of white workers if nothing was done to curb the immigration. “Is it not possible,” the report asked, “that free white labor, unable to compete with these foreign serfs, and perceiving its condition becoming slowly but inevitably more hopelessly abject, may unite in all the horrors of riot and insurrection, and . . . extirpate with fire and sword those who rob them of their bread?”

Dennis Kearney

Congress temporized for a while. Indiana’s Senator Oliver P. Morton dissented from the report of the Joint Special Committee, and Morton was not alone in opposing the demands of California’s white workers. Many churchmen feared that the Chinese government would suppress Christian missionary activities if the United States restricted immigration from China, while eastern merchants feared the loss of foreign markets and western employers continued to covet cheap la-bor. Another stumbling block in the way of Chinese exclusion was the Burlingame Treaty of 1868, which had granted the Chinese the right of unrestricted immigration.

Finally, in 1882, Congress closed the door to immigrants from China. At first the exclusion was temporary, with immigration suspended for only ten years. But the policy was later renewed, and it remained in force until 1943. In achieving this exclusion, white Californians benefited from the fact that national politics in the 1880s was in a state of equilibrium. It was a decade when the two major political parties were so evenly balanced that neither was able to win two consecutive presidential elections. In these circumstances, Republicans and Democrats alike sought the support of California, even if it meant departing from America’s past policy of unrestricted immigration.

The exclusion slowed but did not stop immigration from China, and anti-Chinese outbursts continued — with most modeled after one or the other of two approaches that Professor Pfaelzer calls “The Eureka Method” and “The Truckee Method.” In Eureka, a lumber town on California’s north coast, a purge occurred in 1885, after a white city councilman, David Kendall, was killed in a crossfire when two Chinese men shot at each other. Within a few hours several hundred indignant white men gathered at a city hall and commissioned a committee of fifteen to go to Chinatown and order the Chinese to leave Eureka. Two steamships were in port, and the whites insisted that every Chinese person should be at the docks the following day, ready to sail with the next tide. Whites then built a scaffold and affixed a warning, “ANY CHINESE SEEN ON THE STREET AFTER THREE O’CLOCK . . . WILL BE HUNG TO THIS GALLOWS.” Within 48 hours the 300 Chinese residents of Eureka had left for San Francisco.

Observing the scene, the Eureka Daily Times commented in language that reflected the racial tensions that had prevailed when the Chinese were driven out. Under the headline “WIPE OUT THE PLAGUE SPOTS,” the newspaper declared:

In the very heart of the city of Eureka is a community in which exist slums and festering dens. . . . Our readers will not stop to ask for the location of this leprous quarter. They know it too well. . . . It is the pestilential quarter where Chinese gambling dens, opium smoking hell-holes, and the lowest brothels abound. They know that this leper’s colony is a curse to the city and its future prosperity.

Later, in an effort to entice white people to settle in Humboldt County, where Eureka was located, the Chamber of Commerce boasted that “one fact makes Humboldt unique among the counties of California . . . we have no Chinese.” The Chamber went on to explain:

There was a time when the Chinese had quite a colony here, but in one of the “tong” wars a stray bullet from the pistol of a highbinder struck and killed a prominent citizen of Eureka, who was passing along the street. The community rose as a man and drove every Chinese out of the county. No violence was used. They were compelled to go. That was in 1885, and since then Humboldt has had no Chinese. Even in far-off China, the coolies know that they are not permitted to come here, and none ever attempt it.

Whites in Truckee used a different method to achieve a similar result. Located near the crest of the Sierra Nevada, Truckee was a logging town that had been inundated with young Chinese men after construction of the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. During the 1870s about one-third of the town’s population was Chinese, and in the 1880s Charles McGlashan, a local attorney and newspaperman, developed a strategy to drive the Chinese out of the mountain town. Rather than resort to vigilante activities, which others had employed from time to time, McGlashan called for “a strict and strangling economic boycott — one that would publicly shame white businessmen who em-ployed Chinese laborers.” At first the vigilante element ridiculed McGlashan’s approach, but McGlashan understood that white women who employed Chinese servants were opposed to racial violence, as were businessmen who hired Chinese workers. McGlashan therefore proposed to turn “attention away from the Chinese” and to focus in-stead on their employers. He would use his newspaper to persuade the local whites “that a boycott of Chinese workers was in the ‘interests not only of the laboring men but of the entire community.’” His goal was to persuade white employers as well as white workers. He wanted to persuade “not only the laboring man, but the entire community [to] demand that all individuals, companies and corporations should dis-charge any and all Chinamen in their employ . . .”

In 1885 and 1886, McGlashan and his supporters established “Committees of Five” that urged local businesses “to hire and buy white.” Similar groups persuaded local banks to call in loans they had previously given to Chinese businessmen. When some proprietors of hotels and boarding houses refused to fire their Chinese workers, McGlashan persuaded their white lodgers to move out — whereupon the proprietors recognized the wisdom of supporting the boycott. McGlashan’s most significant victory occurred in February, 1886, when Sisson, Crocker, and Co., perhaps the largest employer in the northwest, agreed to cancel its contracts with Chinese lumbermen and call in its loans.

McGlashan eventually became a statewide leader of Chinese expulsion — a Denis Kearney of the smaller towns — and he telegraphed an outline of his approach, “How to Boycott,” to newspapers across California. “Select the strongest, wealthiest firm and the one who is seemingly most impregnable. . . . Search out all his patrons, and boycott his productions, not only at home but abroad.” Every employer in the state could “be forced to discharge his Chinese” or “be ruined.” Then, McGlashan recommended, “receive the vanquished firm into the fold as soon as it surrenders. The fox whose tail is clipped will be eager to have the tails of other foxes clipped. The man who is compelled to dis-charge his Chinese will render valuable assistance in bringing his business rivals to terms.”

By the end of 1886, only a handful of Chinese remained in Truckee, and boycott clubs were springing up in cities and towns throughout California. With evident satisfaction, McGlashan declared that the Chinese had been “driven out of Truckee by peaceful means.” “Blows [that] struck at pocket-books and bank accounts” had “prove[n] more telling than violence or incendiarism.” Some of the departing Chinese moved to British Columbia. Others returned to China and still others accepted invitations to settle in Mexico. Most made their way to either San Francisco or Los Angeles, where they retreated into ethnic colonies known as “Chinatown.”

Historial Assessments

Historians have written conflicting assessments of the anti-Chinese movement. The upper-class white authors of the earliest scholarly works showed little sympathy for the movement. In his classic work of 1890, a seven-volume History of California, Hubert Howe Bancroft acknowledged that “the presence of the Chinese in California reduced the chances and earnings of citizen laborers, while it strengthened the power [of agro-business and industry] by adding to the wealth of capitalists.”Nevertheless, the WASP professor from Berkeley evinced distaste for the tactics of the white workers, and for their predominantly Irish ethnicity as well. Similarly, Lord James Bryce, writing in 1893, had few good words for the anti-Chinese movement. Lord Bryce described the white rank-and-file as “rabble” and “hoodlums.” Searching for something positive, he could say only that, thanks to interventions by the courts, “not much evil was wrought.” “The net result of the whole agitation was to give the monied classes in California a fright; to win for the State a bad name throughout America, and, by checking for a time the influx of capital, to retard her growth. . .” Writing in 1909, sociologist Mary Roberts Coolidge penned an especially severe indictment of the white workers. Most Californians were not anti-Asian, Coolidge insisted. Such views were “confined to a class of workingmen” and to “political aspirants of the lower grade.” Dr. Coolidge commented in particular on “the large proportion of Irish” workers who had shown “violent antipathy to the darker races, and have brought with them from Ireland the tradition of turbulency.” Dr. Coolidge noted that “the enforcement of anti-Chinese legislation before 1882 . . . and the administration of the exclusion laws since that time, [were] largely in the hands of men of Irish birth or parentage.”

Prominent labor historians also sympathized with the working whites of California. John R. Commons endorsed the statement of a workers’ convention of 1870: that “the present system of the immigration of . . . coolie labour in these United States is ruinous to the life principles of our Republic, destroying the system of free labour which is the basis of a republican form of government.” Philip Taft concluded that there was “no doubt” that the competition of Chinese workers in California “undercut native and other immigrant workers, and that their living standards and demands were lower than [those of] white workers.” According to Selig Perlman, “The anti-Chinese agitation in California, culminating as it did in the Exclusion Law passed by Congress in 1882, was doubtless the most important single factor in the history of American labor, for without it the entire country might have been overrun by Mongolian labor and the labor movement might have become a conflict of races instead of one of classes.”

For many years almost all discussions of the subject incorporated the California thesis. Yet opinions began to shift after Stuart Creighton Miller, a historian at San Francisco State University, published an influential book in 1969, The Unwelcome Immigrant: The American Image of the Chinese, 1785–1882. In this work Professor Miller demonstrated that a generation before the first Chinese immigrants arrived in California, white Americans in the East and Midwest had developed unfavorable impressions of China. He showed that many white traders, diplomats, and missionaries regarded the Chinese as depraved, filthy, diseased, and superstitious, and he noted that popular newspapers reiterated these views. Professor Miller also explained that the diffusion of negative views was facilitated by three larger developments. One was the new germ theory of diseases, which led medical authorities to fear that Asian epidemics might spread to other populations. Another was the vogue of Social Darwinism, which held that biology influenced culture, and thereby suggested that the Chinese by nature were unassimilable. The third was a free labor ideology that condemned not only American Negro slavery but other forms of unfree labor as well.

Professor Miller acknowledged that California’s white workers “unquestionably catalyzed the movement for [Chinese] exclusion.” But he insisted that the California thesis placed too much emphasis on developments in the American West.

Californians did not have to expend much effort in convincing their compatriots that the Chinese would make undesirable citizens. The existing image of the Chinese in America had already done it for them. For decades American traders, diplomats, and Protestant missionaries had developed and spread conceptions of Chinese deceit, cunning, idolatry, despotism, xenophobia, cruelty, infanticide, and intellectual and sexual perversity.

While emphasizing the importance of prevailing attitudes, Professor Miller did not try to determine whether the negative images were an accurate rendition of reality. Nevertheless, he implied that ethnocentric prejudice and ill will had distorted the judgment of most white people. He depicted American attitudes toward the Chinese as “not only largely negative, but also distinctly racist.”

At first, some authorities considered Professor Miller’s view “too harsh.” “Californians exaggerated the unsavory facts to buttress their . . . arguments,” Professor Light acknowledged. Nevertheless, “organized vice, filth, despotic government, and slavery did, indeed, characterize Chinese colonies in California, Southeast Asia, and even in South China cities. That is one reason the reports from California con-firmed what missionaries, traders, and diplomats had earlier relayed from China.”

As the civil rights movement spread across America, however, more and more historians insisted that the shortcomings of the Chinese were not sufficient to explain the movement to drive them out of so many places. Instead, historians who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s emphasized the importance of white racial prejudice, which they insisted had been prevalent throughout the course of American history. As attitudes toward race changed, historian Roger Daniels has written, scholars came to see the “mistreatment of Asian immigrants . . . as an integral . . . part of a larger whole, American racism.”

The Indispensable Enemy (1969), by Alexander Saxton, was one of most influential of the “new” histories. Saxton was born in 1919, joined the Communist Party in the early-1940s and, with the publication of Grand Crossing (1943), became one of the most successful authors of what was called “proletarian fiction.” Another novel followed in 1948, but after that the mood of the nation moved to the right, and Saxton found it difficult to make a living as a left-wing novelist. In the 1960s he enrolled in Berkeley’s graduate program in history, and he eventually became a professor at UCLA. Professor Saxton’s first scholarly book, The Indispensable Enemy, recounted the usual social and economic reasons for ousting the Chinese. But The Indispensable Enemy also offered an explanation that went beyond the familiar cheap-labor arguments. It situated the anti-Chinese movement in the context of larger intellectual trends, and especially in the context of white American racism.

Professor Saxton found that white racial consciousness was deeply rooted in the Anglo-American past and had come to the fore among ordinary workers during the age of Andrew Jackson. Rather than regard the anti-Chinese movement as a response to conditions in the West, Professor Saxton pointed to “patterns of thought which . . . stemmed from the Jacksonian era in the East.” It was in the East, and long before Chinese immigrants arrived in California, that white workers had developed a sense of racial identity and consciousness. Like most Marxist writers, Professor Saxton thought this racial identity was shortsighted, for it impeded the development of multiracial working-class solidarity. Instead of advancing the best interests of working people, white racial consciousness gave rise to a false consciousness. It led whites to think, mistakenly Saxton believed, that “every country owes its first duty to its own race and citizens.” Even the usually perceptive left-liberal economist and social philosopher Henry George made this mistake when he wrote, “we should have a care for those of our own race who will follow us.”

Other writers have also emphasized the importance of white racial consciousness. Perhaps the most influential is the Berkeley historian Ronald Takaki who has noted that, although his grandfather came to America from Japan in the 1880s, many American whites do not regard him as “a fellow American.” “My eyes and complexion looked foreign.” And so it has been for other Asian Americans, for more than a century. They have also learned that, regardless of their citizen-ship or degree of assimilation, they are still regarded as “foreigners.” According to Professor Takaki, “whites generally perceived America as a racially homogeneous society and Americans as white. Long be-fore the Chinese arrived, they had already been predetermined for exclusion by this set of ideas.”

Professor Takaki has been especially influential because he can write with great clarity — eschewing the excessively abstract concepts and theoretical language that make some academic writing difficult for many readers. He has an especially good eye for compelling stories and apt quotations, and he makes good use of engaging first-person accounts that immigrants themselves penned. Writing in the London Economist, one reviewer recommended one of Professor Takaki’s books, A Different Mirror (1993)“to anybody wanting a swift introduction” to the history of American immigration. Another re-viewer, writing in the New York Times, adjudged another of Professor Takaki’s books, Strangers from a Different Shore (1989), as “the best volume yet published on the subject.”

Others of Professor Takaki’s books have been more theoretical. One reviewer described Iron Cages (1979) as “encumbered by jargon and difficult English.” But that may have increased its appeal to fellow academics. In this volume, Professor Takaki noted that nineteenth-century American whites praised the work ethic and disparaged people whose behavior seemed more instinctual. Translated into racial terms, whites lauded middle-class Caucasians and condemned Indians and Negroes as savage, barbarian, primitive, ignorant, sensual, or lazy. At the same time, Professor Takaki maintained, whites paid a price for repressing spontaneity in their own lives. While denigrating people of color for their alleged lack of self-control in their emotional and sexual lives, whites subjected themselves to excessive self-repression. In the process of defaming colored peoples, whites developed a cultural pathology. While expropriating Indians and enslaving blacks, whites placed themselves in an Iron Cage.

Iron Cages blazed a path for other academics who would write about Asian Americans. Professor Takaki pathologized racial identity among whites. He maintained that group consciousness among Caucasians was a form of psychiatric illness.

At first, some influential reviewers took exception. George M. Frederickson chided Professor Takaki for engaging in “some ethnic stereotyping of his own,” a sort of racism in reverse. Theodore Rosengarten concluded that Iron Cages was “a bad book. Bad because it fails to enlighten or entertain.” Meanwhile, John J. Miller said another of Professor Takaki’s works was “disgraceful” — because it allegedly depicted America’s non-white populations as victims of pervasive white racism, because it said “virtually nothing about [the minorities’] record of economic and cultural achievement,” because it portrayed America “as a bleak sinkhole of wasted efforts and futile hopes.” Ken Masugi made similar points, and C. Vann Woodward opined that “no per-son of reasonable sensibilities would willingly claim identity with a country justly found uniquely capable of policies ascribed to America . . .” Professor Woodward conceded that “works of this sort” were “find[ing] a place,” but he predicted that they would remain popular only “so long as the current mood of collective self-denigration and self-flagellation will prevail.”

Despite the unfavorable early reviews, Iron Cages presaged a new trend in American historiography, one that depicted white racial consciousness as not only deeply rooted in the American past but also as a pathological condition. Alexander Saxton elaborated on these themes in a book of 1990, The Rise and Fall of the White Republic. Other scholars chimed in, and before long “whiteness studies” became fashionable. Starting with the premise that race was an ideological or social construct rather than a biological fact, whiteness scholars depicted white racial consciousness as the key to understanding American history in general, and especially to understanding exploitation and injustice.

Going beyond left-leaning labor historians who had lamented that white racial identity made it harder to forge a working-class conscious-ness from which a mass socialist movement might emerge, whiteness scholars equated white racial identity with white racial bigotry. Whiteness writers also parted company with earlier intellectual historians who had depicted white racial consciousness as simply a justification for exploiting the labor and expropriating the land of other racial groups. The whiteness writers insisted that white racial consciousness was deeper, and more perverse, than that. The goal of whiteness writers was to expose the alleged pathology of white identity and to cultivate a sense of white racial guilt. According to David Roediger, one of the most influential of the whiteness writers, “It is not merely that whiteness is oppressive and false”; “it is that whiteness is nothing but oppressive and false.” One whiteness journal, Race Traitor, proclaimed that “treason” to white racial consciousness and white racial identity was “loyalty to humanity”

In some ways the civil rights era would seem to have created a hostile environment for writers who decried racial consciousness. It was a time, after all, when African Americans and Hispanics celebrated a sense of racial identity and pride, as was reflected in popular slogans like “black is beautiful” and in the very name of one influential Mexican-American organization, La Raza. It was a time when a popular slogan proclaimed, Por la raza, todo; fuera de la raza, nada. “We will do all we can for our race. For other races, we will do nothing.”

Nevertheless, whiteness writers enjoyed great influence, and eventually a double standard became fashionable at many universities and among the elite media. In 1995 the Washington Times fired editorial writer Samuel Francis for maintaining that European Americans also had a right to view themselves as a cohesive group with special interests. As the black writer Shelby Steele has noted, “[B]eyond an identity that apologizes for white supremacy, absolutely no white identity is permissible. In fact, if there is a white racial identity today it would have to be white guilt — a shared, even unifying, lack of racial and moral authority.”

By way of explanation, Dr. Steele resorted to sweeping generalizations about “the extraordinary human evil” that whites have exhibited at one time or another, while ignoring instances of slavery, conquest, genocide, and repression by non-whites — instances that persist to this day in parts of Africa and Asia. According to Dr. Steele:

No group in recent history has more aggressively seized power in the name of its racial superiority than Western whites. This race illustrated for all time — through colonialism, slavery, white racism, Nazism — the extraordinary human evil that follows when great power is joined to an atavistic sense of superiority and destiny. That is why today’s whites, the world over, cannot openly have a racial identity.

Several white writers have agreed. James Traub, a liberal writer, has asserted that accepting “collective [white] responsibility — guilt” — is an essential “precondition” for whites who wish to enter “the con-temporary discussion [about race].” Joe Klein, another liberal writer, has insisted that whites must begin a discussion of race with a confession: “It’s our fault; we’re racists.” Writing from a different perspective, Jared Taylor has lamented:

Every other race is thought to have good reason to speak of collective achievement, to have collective interests, and to have collective goals as a group. For whites all of this is washed away in an ocean of collective guilt for having oppressed non-whites. This . . . is the only way in which whites are allowed . . . to have a group consciousness. The meaning of whiteness . . . consists of affirming collective guilt. . . For almost all whites . . . the only occasion in which they speak as whites is to apologize.

Yet the whiteness ideology rests on a shaky foundation. It starts with the premise that race is an ideological or social construct rather than a biological reality, but this concept is not widely accepted either by generally educated Americans or by scientists familiar with recent research on population genetics. By the turn of the twenty-first century, most educated people recognized that DNA is real stuff, and as the results of the Human Genome Project were disseminated it became harder to believe that “race” is merely “a social construct.” Whiteness writers would have been on firmer ground had they insisted that racial bigotry, not race, was a social construct. Nevertheless, many whiteness writers have soldiered on. Writing in The American Historical Review in 2007, Professor Michelle Brattain insisted that historians should persist with their “consensus that race is a social construction” even though “the racial identification of genomic types”and other “current fad[s]” in science had led “many people outside the humanities and social sciences” to conclude that race is a biological reality.

The controversy had been roiling for decades. An early indication occurred in 1950, when UNESCO published a statement that claimed that race was merely a “social myth.” So many physical anthropologists and geneticists took exception that UNESCO felt compelled to supplement this report in 1951 with a second statement that did not endorse a social-constructivist view. More recently, medical re-searchers have recognized that, because there are racial differences in the way people respond to medical treatments, sick people will be harmed if medical science endorses the idea that race is purely a social construct. The full extent of the nature and significance of racial difference is not yet a settled question. But there is little doubt about which way the wind is blowing. Richard A. Schweder, a professor at the University of Chicago and the president of the Society for Psycho-logical Anthropology, put it this way in the New York Times: “Anyone who has lived long enough in the social sciences has seen the nature-nurture pendulum swing from nature in the first decades of the [twentieth] century, to nurture in the 1930’s, 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s, once again in the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s.”

Some scholars concede that racial differences are biological realities but nevertheless say that dissimilarities are limited to superficial features such as skin color, hair texture, and other matters of physical morphology. Others insist that racial differences also affect behavior, culture, and intelligence. Thus Samuel Francis, the longtime book editor at The Occidental Quarterly, has written, “we now know enough about the biologically grounded cognitive and behavioral differences between the races to be able to say with confidence that race deeply affects and shapes cultural life.” Erstwhile TOQ editor Kevin Lamb has also maintained that racial differences are neither minor nor in-significant, while TOQ contributor J. Philippe Rushton has done more than perhaps anyone to document the nature and significance of these differences.

In Driven Out, Professor Pfaelzer endorses both the “cheap labor” argument and the “whiteness” thesis. Professor Pfaelzer shows that the expulsions were “spurred on by Irish and German immigrants fearful of job competition and by destitute, unemployed white migrants from the East Coast . . .” She recognizes that white people were divided along class lines, and that white workers condemned “the capitalists, ship owners, and merchants who profited by transporting or hiring Chinese laborers.” But Professor Pfaelzer knows it is hard to determine “whether race trumps class or class trumps race.” Knowing this, she persuasively states, “Racial issues and economic pressure together provided a platform for the Chinese roundups.”

Jean Pfaelzer

Driven Out is not as theoretical as the works of most whiteness scholars, but Professor Pfaelzer plumps primarily for a racialist explanation. She points out that “ideas of racial inferiority and white purity” had a long history in the United States. She notes that “before it rolled through northern California” a racial ideology had been used to justify the taking of land from the Indians and the destruction of Black Reconstruction in the South. She quotes a Chinese immigrant who initially thought “that all opposition . . . came from the Irish,” but later learned that “the whole white people . . . are earnest in their desire not only to restrict [us] coming into the country, but to expel those already here.” She takes notice of the popular slogans of the time, “California for Americans” and “No Place for a Chinaman.” She includes a statement from the private correspondence of an especially prominent Californian, US Supreme Court Justice Stephen Field: “I belong to the class who repudiates the doctrine that this country was made for people of all races. On the contrary, I think it is for our race — the Caucasian race.”

Professor Pfaelzer decries this white racialism. She says, “the purges of the Chinese in the American West bring to my mind Kristallnacht, the night in 1938 when Nazi Germany violently exposed its intention to remove the Jews.” She identifies herself as a Jewish scholar, and she characterizes the Chinese migrants in terms that have commonly been applied to Jews: “a transnational people” whose relationships “spanned borders.” “Even as they sent hundreds of thou-sands of dollars back to China, made frequent visits home, [and] at times maintained families on both continents . . . the Chinese simultaneously fought at every turn for their rights to property and permanence in the new communities of the West.” Because of their struggle against discrimination and their insistence on equal rights, Professor Pfaelzer ranks the Chinese among the pioneers of the modern civil rights movement.

Another Point of View

Readers of The Occidental Quarterly will understand that some of Professor Pfaelzer’s normative judgments differ from those of several editors and contributors to TOQ. These writers would agree with Professor Pfaelzer on one point: that white racial identity and conscious-ness have been pervasive in the United States and are deeply rooted in American history. Instead of decrying white racialism, however, most TOQ writers have celebrated the phenomenon. Thus the long-time associate editor of TOQ, Samuel Francis, approvingly maintained that John Jay expressed the conventional wisdom of America’s Founding Fathers when Jay wrote, in The Federalist Papers:

Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country to one united people — a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs.

Jared Taylor, who once served on TOQ’s editorial board, has expanded on this point. With citations to Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, and many other prominent Americans, Taylor showed that:

The great majority of Americans up until the 1950s and 1960s . . . believed that race was a fundamental aspect of individual and group identity. They believed people of different races differed in temperament and ability, and that whites built societies superior to those of non-whites. They took it for granted that America must be peopled with Europeans and that European civilization could not be maintained without Europeans. Many saw the presence of non-whites in the United States as a terrible affliction, and believed that if non-whites could not be removed from the country entirely they should be separated from whites socially and politically.

Taylor has further maintained that human beings (and other groups of animals as well) have an instinct for homogeneity. Noting that people everywhere make sacrifices for their families and close relatives, and that they seem to do so instinctively, Taylor (quoting the Belgian scholar Pierre L. van den Berghe) has written: “The degree of cooperation between organisms can be expected to be a direct function of the proportion of the genes they share; conversely, the degree of conflict between them is an inverse function of the proportion of shared genes.” According to Taylor, “consciousness of kind” exists throughout the animal kingdom. Thus, chimpanzees, “our nearest liv-ing relatives,” live in bands, “drive off intruders from other bands,” and generally “show a ferocious in-group and out-group consciousness.” “Even bees know who their relatives are. In one experiment, bees were bred for 14 different degrees of relatedness — sisters, cousins, second cousins, etc. — to bees in a particular hive. When these bees were released near the hive, guard bees had to decide whom to let in. They distinguished between degrees of kinship with almost perfect accuracy, letting in the closest relatives and chasing away the more distant kin.”

Consciousness of kind is widespread. In his Guide to the Panorama of North American Mammals, University of Kansas biology professor Raymond Hall summarized a law of nature: “Two subspecies of the same species do not occur in the same geographic area.” One will inevitably eliminate or displace the other. And Professor Hall included humans in this rule: “To imagine one subspecies of man living together on equal terms for long with another subspecies is but wishful thinking and leads only to disaster and oblivion for one or the other.”

Other writers have weighed in with similar observations. Patrick J. Buchanan has noted that several European wars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries occurred when ethno-national groups tried either to join together or to secede from the multi-ethnic empires of the Ottomans, the Russians, and the Austro-Hungarians. More recently, tribal warfare has rent much of Africa. A preference for one’s own kind has also been evident in myriad other ways. Harvard sociologist Robert Putnam, the author of the celebrated book, Bowling Alone, has reported that more people withdraw from community activities when ethnic diversity increases in neighborhoods and towns. Heterogeneity apparently reduces civic engagement. Other researchers have noted what is sometimes called “the Florida effect” — the reluctance of white taxpayers to fund public schools for children of a different race. Still others have suggested that European states have more welfare pro-grams than the United States because the populations of the European nations are more homogeneous than the population of the United States. Many people apparently believe that charity begins at home, with one’s own people.

The history of school integration provides more evidence that human beings have deep-rooted tribal instincts. As the sociologist James S. Coleman has demonstrated, since the 1970s white parents have thwarted the designs of federal judges and liberal school administrators. When federal judges ordered busing for racial balance, and when school administrators pushed for proportional mixing within schools, many white families fled to predominantly white schools and to predominantly white neighborhoods and suburbs. After carefully examining the relevant statistics, Professor Coleman arrived at a rule of thumb: an increase of 5 percent in a white child’s black classmates would cause an additional 10 percent of white families to leave. Thus the United States faced an “insoluble dilemma.” There would be no racially balanced integration without court-ordered busing, but such busing had the overall effect of defeating integration. The official push for school integration was offset by the actions of white families who moved from areas where there was a large enrollment of black students to areas where there was less racial mixing.

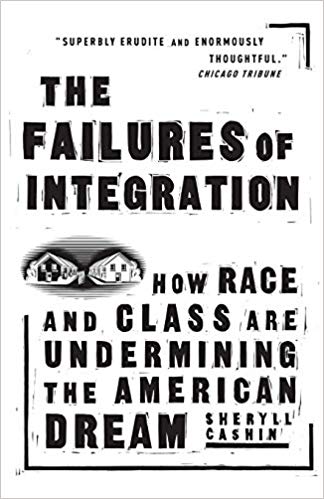

A similar pattern is apparent in housing. When offered the choice of neighborhoods that are racially mixed or racially homogeneous, most Americans choose to live in areas where their own race pre-dominates. Some scholars attribute this to “redlining” and other “nefarious practices.” Douglas S. Massey and Nancy A. Denton, for example, decry the pattern of settlement as American Apartheid. But Harry Edwards, a black sociology professor at the University of California at Berkeley, rejects the contention that residential concentration is primarily a result of malign forces that restrict non-whites to colored enclaves. According to Professor Edwards, residential integration “has not been approached or achieved because nobody wants it.” Many minorities simply feel more comfortable living among other members of their race. In The Failures of Integration, Sheryl Cashin, a black professor at Georgetown University, also noted that many well-to-do African Americans consciously choose to live in upscale suburbs that are mostly black. Well-to-do whites also choose to live among “their own kind,” although they recognize that it is politically incorrect to express a desire to live apart from non-whites. Nevertheless, money talks, and Professor Cashin calculated that “the white tax” — the extra expense that whites pay for a comparable home in a white neighbor-hood — is 13 percent nationwide. In some areas, it is much more.

Large demographic studies provide still more evidence on this point. After studying 240 metropolitan areas during the 20-year period from 1980 to 2000, one group of researchers emphasized the persistence of racial concentrations in the neighborhoods. Although the gap between black and white incomes narrowed in some places, “we saw no [neighborhood integration] effect from the growing convergence of black and white incomes.” Similarly, a statewide survey in California found that a majority of all groups — whites, blacks, Hispanics, and Asians — agreed with the statement, “people are happier when segregated.”

Through much of history white leaders were considered heroes be-cause of their racial or ethnic loyalties. One thinks of King Leonidas and the Spartans, who stood at Thermopylae to defend Greece against an invasion from Persia; of Charles Martel and Jan Sobeiski, who de-fended Europe against the Muslims; of William Wallace and Robert Bruce who battled for the Scots against the English. For thousands of years, white ethnic groups have honored leaders who defended the interests of their people.

White racial consciousness and identity have been “delegitimized” in the years since World War II. Nevertheless, vestigial remnants have persisted and continue to influence the behavior of many people. The power of ancient attitudes has been suppressed by the cultural programming of modern multiculturalism, but evolution apparently has equipped whites with an unconscious disposition to band together. That, at least, is the opinion of psychologist Kevin MacDonald — another of TOQ’s authors and editors. Professor MacDonald has noted that rank-and-file whites have rejected the exhortations of their modern elite and are “gradually coalescing into . . . communities that reflect their ethnocentrism.” Many of these whites do not openly challenge the conventional wisdom about the value of diversity, but they stick together when it comes to choosing friends, schools, and neighborhoods. “There is a profound gap between the implicit attitudes and . . . behavior [of whites] (which show ingroup racial preference) . . . and the explicit attitudes (which express the official racial ideology of egalitarianism).”

Michael W. Masters, yet another writer for TOQ, has offered an evolutionary explanation for what he calls “a dual code of morality.” Drawing on evolutionary psychology, Mr. Masters maintained that altruism initially developed within small bands of people. These bands (and later, larger groups, tribes, and nations) would not have survived without developing a consciousness of kind, a willingness to act on behalf of the group, a readiness to make sacrifices for the group.

Yet it was a mistake, Mr. Masters insisted, to think that altruism could be extended “beyond its evolutionary origin . . . to the whole of humanity.” Any tribe, group, or nation would be headed for extinction if it practiced “universalism” — that is, “altruism without discrimination of kinship, acquaintanceship, shared values, or propinquity in time and space.” “Any idealistic group that unilaterally dismantles its own tribal sense will be swept away by groups that have retained theirs.” “Groups that practice unlimited altruism, unfettered by thoughts of self-preservation, will be disadvantaged in life’s competition and thus eliminated over time in favor of those that limit their altruistic behavior to a smaller subset of humanity.”

Mr. Masters insists that it is “moral for ethnic groups as well as individuals to seek survival.” Therefore, he has urged Caucasians to maintain a “dual code of morality, an altruistic code for one’s genetic kin and a non-altruistic code for everyone else.” This is necessary for survival, and it is a “normal and natural . . . extension of the biologically necessary fact that parents love their children more than the children of strangers.”

The “whiteness” writers, and also Professor Pfaelzer, do not share these Occidental views. Instead, they regard Caucasian racial loyalty as despicable “white racism.” However, most of the nineteenth century Americans who sought to exclude the Chinese embraced Occidental views long before TOQ was established. As erstwhile TOQ book editor Wayne Lutton has noted, many of the restrictionists of yesteryear were motivated more by loyalty to their own race than by bigotry against others. The best of the restrictionists cast no aspersions on the Chinese or on others from Asia. But they insisted that the United States should limit and control immigration, “as a simple matter of self-preservation . . . because the future of the white race, American institutions, and western civilization are . . . in peril.” Believing that they owed a debt to their ancestors and had a responsibility to pro-vide for their progeny, the racially conscious whites of yesteryear felt an obligation to “preserve the soil for the Caucasian race.”