Race is Real

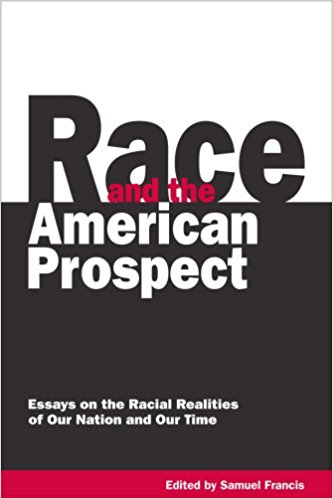

Kevin Lamb, Race and the American Prospect, 2006

It will, I think, be generally admitted that the ideal classification of the races of man is yet to be proposed. The existing ones are tentative, but they serve as cataloguing devices. Yet it does not follow that races are arbitrary and “mere” inventions of the classifiers; some authors have talked themselves into denying that the human species has any races at all! Let us make very clear what is and what is not arbitrary about races. Race differences are facts of nature which can, given sufficient study, be ascertained objectively: Mendelian populations of any kind, from small tribes to inhabitants of countries and continents, may differ in frequencies of genetic variants or they may not. If they do so, they are racially distinct. — Theodosius Dobzhansky

Undoubtedly there are racial characteristics. The longer two races have been separated, the greater will be their genetic differences. Populations within a race are more similar to one another than are races. No one would mistake a sub-Saharan African for a western European or an eastern Asian, based on such superficial physical aspects as skin color, eye color, hair, shape of nose and lips, shape of skull, and stature. Genetics and molecular biology have added many other average differences or diagnostic characters. But when it comes to the psychological characteristics that really count, the role of genes is largely undetermined. — Ernst Mayr

The claim is sometimes made on an assumed basis of science that all races of men are biologically equal, and that the differences of capacity which appear are due to opportunity and to education. But opportunity has come to no race as a gift. By effort it has created its own environment. Powerful strains make their own opportunity. The progress of each race has depended on its own inherent qualities. — David Starr Jordan

No other concept that spans the natural, social, and behavioral sciences has generated as much controversy, received as much scrutiny, provoked as much disputable rhetoric, or prompted as much deception as the idea of race. Eminent scientists, philosophers, statesmen, and distinguished scholars throughout history have recognized the concept of race (in general) and racial differences (in particular). In addition to the eminent biologists and educators quoted above, various men of exceptional accomplishment, such as Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, Benjamin Franklin, Francis Galton, Karl Pearson, Edward Lee Thorndike, Ellsworth Huntington, Edward M. East, Immanuel Kant, David Hume, Jean Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Thomas Carlyle, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, have recognized the fundamental racial divisions of mankind. Until quite recently, the notion of biological racial differences has been commonly accepted among educated elites in western societies.

In fact, one can attribute the emergence of “political correctness” to a modern strategy by which egalitarian elites seek to minimize the significance of race in explaining racial anomalies. By airbrushing racial differences out of racial disparities, society’s egalitarian gatekeepers have established perimeters of acceptability when confronting stubborn racial inequalities. The educated layman who depends upon mass-market publications (newspapers and news magazines) for information encounters a steady intellectual diet of proxy explanations for racial differences in socioeconomic and educational disparities — egalitarian explanations which view such disparities as resulting from “slavery,” “oppression,” “segregation,” “prejudice,” “discrimination,” and “cultural deprivation.”1 Political correctness serves as a filter for egalitarians to explain away persistent racial patterns in society — e.g., disparities between the races in test scores, academic performance, crime rates, personal income and wealth, rates of welfare use, sentencing and imprisonment, patterns in life expectancy, the prevalence of diseases (particularly HIV infection rates), and other quality of community life issues.

The ideological orthodoxy that forbids racial explanations for persistent racial trends can be viewed as a way for societal elites to manipulate rational perspectives on the subject of race — a filter for distinguishing “acceptable” from “unacceptable” truths — especially when such views are exchanged in public forums such as serial publications, monographs, think tank reports, and academic panel discussions. Racial taboos, in essence, deliberately dissuade informed public elites from candid discussions of racial differences. Given the magnitude of racial taboos, a subject that is routinely avoided in cordial discussions, the topic of race — when accepted as a “social construct” — continues to generate a vast trove of academic and popular literature. The bulk of this literature dwells on the supposed lingering ramifications (“racism”) of a supposedly nonexistent concept (race). For the independent-minded rationalist, the irony of racism’s toxic threat to civil society is the fact that a meaningless idea as trivial as “race” continues to generate volumes of critical analysis under various academic subfields, such as multicultural, ethnic, and “critical race studies.” Basically, a “societal” phenomenon known as “racism” continues to exert considerable negative consequences as a force that is allegedly based upon (a) misperceived “stereotypes” and (b) a “social construct” entirely devoid of any empirical biological realities. How can “racism” reflect, on the one hand, such an obvious widespread condition (group-based discrimination) when the physical basis for distinguishing such groups (races) is nonexistent? How can “racism” generate sustained intense interest when its antecedent, “race,” is so invalid a concept in the first place? Hence, the confusion and misunderstanding over the meaning and subsequent reality of race have never been greater.

Much of this distortion reflects the intellectual milieu of the modern era. Natural and social scientists during the early part of the twentieth century were unambiguous as to their understanding of the biological realities of race. While scholars may have differed over the degree of importance that race played in human affairs during the early 1900s, few would deny that race was a biological fact of life. (Even prominent sociologists such as Henry Pratt Fairchild, Franklin Henry Giddings, Frank Hamilton Hankins, L. T. Hobhouse, Gustave Le Bon, and Pitirim Sorokin recognized the biological concept of race.) Since the publication of the influential UNESCO document Statement on Race, written largely by the late social anthropologist Ashley Montagu, egalitarian social scientists have tried to nullify and redefine the concept of race. Some contemporary social scientists blatantly reject race as a biological division of Homo sapiens. Accordingly, these egalitarian scholars consider race strictly as a “social construct.” The purpose of this chapter is to examine the merits of this egalitarian critique, reassess the concept of race as a biological classification, and apply some much needed common sense to a rational understanding of the reality of race.

Throughout the post-UNESCO period, egalitarian critics of race have intensified their campaign to discredit the biological meaning of race. Since the 1950s the number of publications (monographs, popular magazines, and academic periodicals) that either reject the traditional view of race or avoid any discussion of heritable racial differences has eclipsed the number of publications that recognize the traditional concept of race and remain open to the study of racial differences. Consider a few examples of this egalitarian mindset. Jonathan Marks, professor of anthropology at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte, claims, “Race is largely a social category, not a biological category. The heredity of race correlates to some extent with genetics, but is principally derived from anon-scientific, or folk concept of heredity.” Alexander Alland, Jr., former chairman of the anthropology department at Columbia University and Guggenheim fellow, argues, “The most important fact about the concept of race, whether it is used in biology or common discourse, is the porous nature of the term.” Alland further refines his argument by noting, “The criteria used by the average person to categorize individuals as African Americans, or members of some other ‘race,’ are, more often than not, based on social rather than genetic identities.” In a cover story for American Outlook, Joseph L. Graves, professor of evolutionary biology at Arizona State University West and author of The Emperor’s New Clothes: Biological Theories of Race at the Millennium, struggles to clarify why race is not a biological concept:

If humans had biological races, there should be some nontrivial underlying hereditary features shared by a group of people and not present in other groups, or possibly average differences that could be made sense of in some statistical way. Biology has developed relatively precise tools with which to examine whether the hereditary characteristics of populations can be classified into geographical races. It is here that the Western socially defined concept of “race” and the biological concept of race diverge. When one attempts to examine any of the physical features that have been used to define human races in our history, the concept breaks down. Skin color, hair type, body stature, blood groups, disease prevalence: none of these unambiguously corresponds to the “racial” groups that we have socially constructed. Thus, the common person distinguishes what he or she perceives to be racial categories by observable physical traits. These physical traits do vary among geographical populations, although not in the ways most people believe. For example, Sri Lankans of the Indian subcontinent, Nigerians and Australoids share a dark skin tone, but differ in hair type and genetic predisposition to various diseases. Further difficulty results from the fact that people commonly link directly observable physical variation in such attributes as intelligence, motivation, and morality.

In rejecting the customary biological meaning of race, Richard Lewontin, Steven Rose, and Leon Kamin, as well as other leading Marxist critics, argue that the concept is too vague and obscure to have any credible validity as a scientific term. Hence, the differences that exist between “racial categories” are minor and relatively insignificant. However, the authors do not fully reject the concept of race, but merely minimize its degree of importance beyond biological categories based on skin color.

But it turns out not to matter much how the groups are assigned, because the differences between major “racial” categories, no matter how defined, turn out to be small. Human “racial” differentiation is, indeed, only skin deep. Any use of racial categories must take its justifications from some other source than biology. The remarkable feature of human evolution and history has been the very small degree of divergence between geographical populations as compared with the genetic variation among individuals.

Are racial differences (a) nonexistent or (b) existent but trivial? Contemporary radical egalitarian theorists of race have pushed the argument beyond the rhetoric of previous generations of Marxist skeptics, who, while disputing the significance of racial differences, at least admitted, as Lewontin, Rose, and Kamin argue above, that “no matter how defined, [racial differences] turn out to be small.” They concede that racial differences exist, no matter how one redefines the categories, but argue that these differences are (a) small and (b) in many instances nonbiological and (c) that genetic variation among individuals is greater than genetic differences between racial groups. Earlier Marxist scholars attempted to minimize the biological significance of racial differences by focusing on what were perceived as significant causal factors in minority group disparities, without completely dismissing the idea of race. The views expressed by Alan Templeton offer another perspective that minimizes the conventional taxonomic categories of race:

The word “race” is rarely used in the modern, nonhuman evolutionary literature because its meaning is so ambiguous. When it is used, it is generally used as a synonym for subspecies (Futuyma, 1986), but this concept also has no precise definition. The traditional meaning of a subspecies is that of a geographically circumscribed, sharply genetically differentiated population (Smith, Chiszar & Montanucci, 1997).

Contemporary criticisms of race, typical of those mentioned above, invariably place too great a threshold for any objective standard of evaluating the validity of race. If race is meaningless in biological terms, is the contemporary use of “variation” and “populations” likewise equally flawed in indicating of human diversity? Are human differences so trivial that the idea of racial variation is completely meaningless? Do racial differences encompass more than, say, physical features, such as skin color? What about differences in hair texture, facial features, bone structure, stature, cranial size and shape? What about behavioral as well as physical traits? Do human populations actually differ in terms of physical and mental attributes that correspond to traditional racial classifications? Are racial differences really that superficial? After all, wouldn’t the concept of diversity encompass differences in peoples as well as cultures? In other words, is there something inherently flawed about the word race — the idea that ancestral kinships are natural categories — despite the fact that the underlying biological realities of variation among populations remain essentially undeniable?

Philosopher Michael Levin argues that disputes over the meaning of race generally indicate quarrels over the word “race” rather than disputes over what the concept empirically signifies. Much of the criticism from egalitarians consists of verbal disputes over “politically correct” meanings of race. What is at issue in such disputes is the hairsplitting sophistry as to whether or not race is a valid taxonomic term regardless of whether the underlying claims about ancestral population differences are real. A good example of the ideological rhetoric of egalitarian semanticists, which appears throughout the “critical race studies” literature (a Marxist-oriented subfield of sociology), appears in a recent issue of ColorLines, a quarterly publication devoted to egalitarian perspectives on race, ethnicity, and multiculturalism. The rhetoric exposes the Orwellian doublespeak of “social justice” advocates who champion the interests of minority “populations” and the cause of “diversity” but likewise reject any biological or physical basis in characterizing population differences:

Race is real because societies have acted as if certain people are inferior based on innate characteristics. Human populations categorized by race have, ostensibly, been racialized. While health status varies among U.S. racialized populations, it’s essential that genetic and biological differences be studied directly, not through the distorting lens of a previous era’s racial thinking. . .

Although racial dividing lines are, ultimately, political, researchers who submit proposals to the NIH [National Institutes of Health] must demonstrate, using Census categories, that their participants will represent the diversity of the U.S. population. The original intent of this rule is to improve the health care for minority populations, but this laudable policy goal has the unintended effect of discouraging researchers from using more subtle distinctions. It conveys the idea that racial distinctions are scientifically meaningful, in spite of significant evidence to the contrary. . .

How we speak is a direct reflection of how we think; the language of race is a crucial policy issue. It’s not enough for researchers to substitute a more politically correct term — such as “ethnicity” or “culture” — and continue to make use of an archaic race concept. The evidence demonstrates that genetic variation does not neatly map onto socially meaningful groups. If we use the idea of “racialized” groups, we emphasize the concept that race is historically contingent. It is important that social justice advocates discourage research that conveys that biologically distinct human races exist, but we should publically [sic] encourage research into genetic variation and bear witness to the very worthwhile national effort to address health inequalities in racialized communities.

Simply substituting other identifying terms (subspecies, populations, ethnicity, culture, etc.) in place of “race” merely skirts the underlying empirical realities that the concept signifies. As Levin points out, in substituting another term for race nothing is lost but a word, yet the question remains unanswered: Are human subpopulations based on origin of ancestry (races) genetically and biologically different or genetically and biologically indistinguishable? Does mankind consist of divergent populations in which race represents a natural division of human lineage? If such racial categories are completely devoid of biological principles, such as differences in terms of gene frequencies, natural selection, or genetic drift — firmly established evolutionary concepts that apply to racial divisions of mankind — and such categorical divisions merely represent cultural and social artifacts, what criteria are used to corroborate such a claim? Where is the evidence that supports this hypothesis? In other words, what body of evidence substantiates the egalitarian view that race is biologically meaningless and that racial differences are mere “social constructs” devoid of any objective empirical or categorical value? What criteria and threshold of proof corroborate egalitarian claims for universal human equality — proof, in other words, that persistent racial inequalities are exclusively the result of “discrimination” or “unequal opportunities”? Such questions highlight the importance of scrutinizing racial realities.

Egalitarian assumptions about human nature underscore the necessity for sorting out fact from fallacy in racial matters. The contemporary literature on race overwhelmingly consists of pseudoscientific books and magazine articles that adopt an egalitarian view toward race, such as Stephen Jay Gould’s Mismeasure of Man, which dismisses modern attempts to measure racial differences in IQ as an invalid scientific endeavor. Implicit in the analysis of race and contemporary social issues is the notion that racial disparities in society are exclusively the result of socioeconomic forces that adversely impact blacks and other racial minorities. This assumption-as-hypothesis — namely, that racial or population differences are entirely the result of social, economic, and cultural forces sans biological or genetic attributes — is an empirical issue that can be verified by applying a little common sense in determining the facts. Researchers generally accept the fact that heredity and environment shape differences in human behavior. The extent to which biological factors influence behavioral differences is a matter of degree, and may often work in tandem with cultural and social factors. Just as different environments can affect biological development (extreme geographical or climatic conditions) or stimulate different neurological and biochemical reactions (increased aggression with higher testosterone levels), genetic and biological differences can generate environmental variance (the influence of personality traits in shaping family life, divorce, adolescent peer relations, onset of delinquency, etc.). However marginal, the factor of race is just as likely to influence cultural norms and socioeconomic outcomes as contemporary assumptions that attribute racial inequalities to society. The former could foster or contribute to racially disparate social phenomena as much as society does. The words of the physical anthropologist A. L. Kroeber, who is generally known for racially egalitarian views, are worth sober reflection:

The drift of this discussion may seem to be an unavowed argument in favor of race equality. It is not that. As a matter of fact, the anatomical differences between races would appear to render it likely that at least some corresponding congenital differences of psychological quality exist. These differences might not be profound, compared with the sum total of common human faculties, much as the physical variations of mankind fall within the limits of a single species. Yet they would preclude identity. As for the vexed question of superiority, lack of identity would involve at least some degree of greater power in certain respects in some races. These pre-eminences might be rather evenly distributed so that no one race would notably excel the others in the sum total or average of its capacities; or they might show some minor tendency to cluster on one rather than on another race. In either event, however, race difference, moderate or minimal, qualitative or quantitative, would remain as something that could perhaps be ultimately determined.

Contemporary racial egalitarian views of intellectuals in the post-1990s era simply reject the concept of race altogether. While an earlier generation of social anthropologists, sociologists, and social psychologists attempted to minimize the importance of race and racial differences, raising skeptical questions over the methods of measuring behavioral differences (e.g., IQ testing) between racial groups for heritable traits, only ideologues of the radical Marxist fringe denied that races differed in physical and biological traits. Graves typifies this line of reasoning:

Race as most people understand it now was socially constructed, arising from the colonization of the New World and the importation of slaves, mainly from western Africa. The ramifications of this concept have persisted to this day. The twentieth century was also the period of the greatest increase in scientific knowledge the world has ever known. As the world struggled with issues resulting from its socially constructed views of race, the biological sciences grew at an unprecedented rate. Developments in biochemistry, molecular biology, and population and quantitative genetics created the preconditions for a rigorous examination of human biological diversity. The early studies, initiated in the 1940s, began to seriously discredit previously existing racial taxonomies. During the later decades of the century, data would accumulate opposing the existence of biological races until finally, in the early 1990s, the biological race concept was thoroughly dismantled.

If race, biologically speaking, is truly meaningless then how could it be determined that the alleged victim in the Kobe Bryant incident, according to Bryant’s lawyers, was said to have had the pubic hair of a Caucasian male in the underwear she was wearing when she submitted to a physical examination after her alleged rape? How could investigators possibly assess the race of her male sex partner based upon a pubic hair sample? If race is in essence biologically meaningless, then the alleged victim’s attorneys have some explaining to do for their client. However, if the concept is a firmly grounded biological reality — as reflected in the work of forensic scientists who analyze blood types, human anatomical measurements, skeletal remains, and DNA markers to identify crime victims and criminal suspects — egalitarian deniers of race have a great deal to explain away.

Egalitarian arguments that deny the reality of race typically rest on common logical fallacies. Any association between average differences in racial traits that corroborate a link between the physical and mental realms is rejected out of hand as stereotyping. Hence, racial disparities in conjunction with comparative social or economic conditions are considered to be the result, rather than the cause, of these disparities; hence, it is simply accepted that actual racial differences have no relationship to racial disparities in the economic, social, or cultural sphere. Another commonly encountered argument is that correlative evidence does not prove causality. Such a skeptical claim could easily be lodged against any research findings that are grounded on statistical methods of corroboration. The same degree of logical scrutiny could just as easily apply to methodological studies of socioeconomic explanations for urban crime or crime rate disparities. Since radical egalitarians consider race to be biologically meaningless, the focus herein is to reconsider the underlying biological reality of race and its importance in human endeavors. The skeptic who rejects reductionist explanations for causal relationships, and instead views cultural or societal disparities in a vacuum, would likewise fail to notice the importance of the active ingredients in various composites — whether the role of DNA in producing biochemical influences on behavior or the importance of eggs, flour, milk, and baking powder in making pancake batter. By avoiding the factor of racial variation, causal explanations for behavioral traits between populations remain not only incomplete, but most likely invalid as well.

The Concept of Race: Definitions and Meanings

One problem with the concept of race is that it has multiple definitions and meanings. The variable nature of the term has conferred a degree of elasticity over time. For example, race and ethnicity have become synonymous in common English usage. This is often used to illustrate the point that race is a dubious biological term. However, nouns frequently have multiple meanings. As a phenotypic trait, race encompasses overlapping realms — the biological, sociological, and cultural. It simultaneously represents a taxonomic classification of mankind — a natural, biological subdivision of Homo sapiens into subpopulations — as well as cultural and social expressions of this subdivision of mankind. Hence the concept of race not only signifies the biological subdivisions of mankind, differentiating human population groups on the basis of physical attributes that are genetically inherited, but also encompasses the nonphysical attributes (cultural, social, and behavioral) that one associates (on average) with different racial groups. As Gates once pointed out, “Race, like all things biological, is a variable term, equally applicable in a wider or narrower sense. Ethnic groups is a narrower term, usually applied to smaller groups than those which generally receive the designation race.” Just as a bridge may represent one thing to an architect and another to an engineer, the concept of race to a zoologist means one thing, to a forensic or physical anthropologist another, and to a population geneticist yet something else. Each one is studying variations on the same theme: Whether skeletal size, bone structure, pigmentation, testosterone levels, or gene frequencies in blood group types, such factors represent differences in human populations. In essence, one could say race signifies z (biology) plus x and y. By its very nature, a phenotypic trait such as race represents a composite of factors.

Over the years, egalitarians have seized on this multiplicity of meanings — the variability of the term — to argue that race is simply an invalid biological concept: Because the term also represents x and y in addition to z, therefore it cannot mean z. Since race has more than one meaning, it is often argued that the concept only represents one (acceptable) true definition — one that is purely subjective, reflects only cultural factors (synonymous with “ethnicity”), and has no biological properties. This smokescreen is used to justify the egalitarian view that race is a nonbiological entity since there are no absolute fixed racial categories. The answer to this is that racial categories — while arguably not fixed on an absolute scale — are nonetheless legitimate boundaries for dividing mankind into distinct population groups. This categorization of racial types is largely consistent with the statistical methods of population genetics that recognize distinct population groups based upon gene frequency ratios rather than fossil evidence. (The qualifier here is largely, because there are intermediate racial hybrids — crosses between racial populations given their interfertility — that often fall between two racial categories.) The conventional view among credible scientists recognizes the existence of three primary races: Caucasoid (white), Mongoloid (yellow), and Negroid (black). Some researchers have identified five primary groups, usually referred to as “geographical races.” Boyd identified genetic markers in blood types to show that frequencies of blood group types varied from race to race and pinpointed six racial variations in blood group distributions. One could describe the three primary stocks as the conventional classification of race, which authorities across multiple fields — from anthropology to zoology — have consistently accepted as the primary racial division of Homo sapiens. A sampling of the most reliable definitions illustrates how egalitarians have seized the issue of multiple definitions to undermine the biological meaning of race and why this contemporary perspective is fallacious.

The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines race in two primary categories with multiple subcomponents:

Race I. A group of persons, animals, or plants, connected by common descent or origin. I. The offspring or posterity of a person; a set of children or descendants. Chiefly poet. Also trans. And fig. 1570. †b. Breeding, the production of offspring. †c. A generation (rare) — 1741.2. A limited group of persons descended from a common ancestor; a house, family, kindred 1581. b. A tribe, nation, or people, regarded as of common stock 1600. c. A group of several tribes or peoples, forming a distinct ethnical stock 1842. d. One of the great divisions of mankind, having certain physical peculiarities in common 1774. 3. A breed or stock of animals; a particular variety of a species 1580. †b. A stud or herd (of horses) 1667. c. A genus, species, kind of animals 1605. 4. A genus, species, or variety of plants 1596. 5. One of the great divisions of living creatures: a. Mankind. In early use always the human race, the race of men or mankind, etc. 1580. b. A class or kind of beings other than men or animals 1667. c. One of the chief classes of animals (as beasts, birds, fishes, etc.) 1726. 6.

Without article: a. Denoting the stock, family, class, etc. to which a person, animal, or plant belongs, chiefly in phr. of (noble, etc.) r. 1559. b. The fact or condition of belonging to a particular people or ethnical stock; the qualities etc. resulting from this 1849. †7. Natural or inherited disposition. . .

II A group or class of persons, animals, or things, having some common feature or features. I. A set or class of persons 1500. b. One of the sexes (poet.) 1590. 2. A set, class, or kind of animals, plants or things. Chiefly poet. 1590. †b. One of the three ‘kingdoms’ of nature (rare) 1707. 3. A particular class of wine, or the characteristic flavor of this, due to the soil. 1520. b. fig. Of speech, writing, etc.: A peculiar and characteristic style or manner, esp. liveliness, piquancy 1680.

Other definitions are less comprehensive than the above entry for race, but consider the similarities in terms of meaning. Here’s the Merriam-Webster entry for race:

Main Entry: 3race.

Function: noun.

Etymology: Middle French, generation, from Old Italian razza.

Date: 1580.

1 : a breeding stock of animals.

2 a : a family, tribe, people, or nation belonging to the same stock b : a class or kind of people unified by community of interests, habits, or characteristics <the English race>.

3 a : an actually or potentially interbreeding group within a species; also : a taxonomic category (as a subspecies) representing such a group. b : BREED c : a division of mankind possessing traits that are transmissible by descent and sufficient to characterize it as a distinct human type.

4 obsolete :inherited temperament or disposition.

5 : distinctive flavor, taste, or strength.

A similar definition of race can be found in Dorland’s Illustrated Medical Dictionary (twenty-sixth edition), which is a standard reference volume for doctors and medical professionals.

race (rās) 1. an ethnic stock or division of mankind; in a narrower sense, a national or tribal stock; in a still narrower sense, a genealogical line of descent; a class of persons of a common lineage. In genetics, races are considered as populations having different distributions of gene frequencies. 2. a class or breed of animals; a group of individuals having certain characteristics in common, owing to a common inheritance; a subspecies.

The Columbia Encyclopedia contains a similar but more detailed definition of race:

Race

[O]ne of the group of populations constituting humanity. The differences among races are essentially biological and are marked by the hereditary transmission of physical characteristics. Genetically a race may be defined as a group with gene frequencies differing from those of the other groups in the human species (see heredity; genetics; gene ). However, the genes responsible for the hereditary differences between humans are extremely few when compared with the vast number of genes common to all human beings regardless of the race to which they belong. Many physical anthropologists believe that, because there is as much genetic variation among the members of any given race as there is between different racial groups, the concept of race is ultimately unscientific and racial categories are arbitrary designations. The term race is inappropriate when applied to national, religious, geographic, linguistic, or ethnic groups, nor can the biological criteria of race be equated with mental characteristics, such as intelligence, personality, or character.

All human groups belong to the same species (Homo sapiens) and are mutually fertile.

Races arose as a result of mutation, selection, and adaptational changes in human populations. The nature of genetic variation in human beings indicates there has been a common evolution for all races and that racial differentiation occurred relatively late in the history of Homo sapiens. Theories postulating the very early emergence of racial differentiation have been advanced (e.g., C. S. Coon, The Origin of Races, 1962), but they are now scientifically discredited.

Attempts at Classification

To classify humans on the basis of physiological traits is difficult, for the coexistence of races through conquests, invasions, migrations, and mass deportations has produced a heterogeneous world population. Nevertheless, by limiting the criteria to such traits as skin pigmentation, color and form of hair, shape of head, stature, and form of nose, most anthropologists agree on the existence of three relatively distinct groups: the Caucasoid, the Mongoloid, and the Negroid.

The Caucasoid, found in Europe, N Africa, and the Middle East to N India, is characterized as pale reddish white to olive brown in skin color, of medium to tall stature, with a long or broad head form. The hair is light blond to dark brown in color, of a fine texture, and straight or wavy. The color of the eyes is light blue to dark brown and the nose bridge is usually high.

The Mongoloid race, including most peoples of E Asia and the indigenous peoples of the Americas, has been described as saffron to yellow or reddish brown in skin color, of medium stature, with a broad head form. The hair is dark, straight, and coarse; body hair is sparse. The eyes are black to dark brown. The epicanthic fold, imparting an almond shape to the eye, is common, and the nose bridge is usually low or medium.

The Negroid race is characterized by brown to brown-black skin, usually a long head form, varying stature, and thick, everted lips. The hair is dark and coarse, usually kinky. The eyes are dark, the nose bridge low, and the nostrils broad. To the Negroid race belong the peoples of Africa south of the Sahara, the Pygmy groups of Indonesia, and the inhabitants of New Guinea and Melanesia.

Each of these broad groups can be divided into subgroups. General agreement is lacking as to the classification of such people as the aborigines of Australia, the Dravidian people of S India, the Polynesians, and the Ainu of N Japan.

Another definition of race can be found in the Encyclopedia of Intelligence (ed. by Robert J. Sternberg). The authors, Edmund W. Gordon and Maitrayee Bhattacharyya, point out:

The Construct of Race. Many scholars have debated definitions of race; however, there has been some consensus as to what the construct refers to. Almost all contemporary definitions of race include some reference to the physical characteristics of the persons referenced. Webster’s New World Dictionary defines race as “any of the different varieties of mankind distinguished by form of hair, color of skin and eyes, stature, [and] bodily proportions.” Most modern anthropologists recognize three primary human groups: Caucasoid, Mongoloid and Negroid. Within each of these three major human divisions, various subdivisions (sometimes incorrectly called races) are recognized. Biologists are inclined to use race to refer to a population that differs from others in the relative frequency of some gene or gene pool patterns.

Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, professor emeritus of genetics at Stanford University, co-author of The History and Geography of Human Genes, and arguably the leading population geneticist in his research field, provides a basic definition of race in his book Genes, Peoples, and Languages:

A race is a group of individuals that we can recognize as biologically different from others. To be scientifically “recognized,” the differences between a population that we would like to call a race and neighboring populations must be statistically significant according to some defined criteria. The threshold of statistical significance for a given distance increases steadily with the number of individuals and genes tested.

Finally, bear in mind the definition from a standard genetics reference volume, A Dictionary of Genetics by Robert C. King and William D. Stansfield:

Race A phenotypically and/or geographically distinctive sub-specific group, composed of individuals inhabiting a defined geographical and/or ecological region, and possessing characteristic phenotypic and gene frequencies that distinguish it from other such groups. The number of racial groups that one wishes to recognize within a species is usually arbitrary but suitable for the purposes under investigation. See ecotype, subspecies.

Consider the logical consistency and conceptual similarities associated with these definitions of race. The concept of race is identified in terms of variation, division of mankind, or population group that are related by ancestral heritage, common descent, or origin, which share a distinct set of physical traits or characteristics unique to each group or subdivision. Underlying this thread of similarities that connects these varying definitions of race is the idea of heredity. Simply put, reasonably definitive sources commonly identify the distinguishing factors of race as fundamentally biological in origin. Contemporary deniers of race claim that because there is so much variation within and across racial categories, therefore there are no racially homogeneous population groups. Races are invalid categories because humans are essentially heterogeneous by definition. Hence, classifying these various subdivisions is simply too arbitrary to maintain consistent accuracy from one classification to another. However, the existence of intermediates or racial hybrids as a result of interracial lineage is insufficient grounds for rejecting the standard biological concept of race. John R. Baker drives this point home in his definitive study of the subject:

It is sometimes claimed that the existence of intermediates makes races unreal. It scarcely needs to be pointed out, however, that in other matters no one questions the reality of categories between which intermediates exist. There is every gradation, for instance, between green and blue, but no one denies that these words should be used. In the same way the existence of youths and human hermaphrodites does not cause anyone to disallow the use of the words ‘boy,’ ‘man’ and ‘woman.’ It is particularly unjustifiable to cite intermediates as contradicting the reality of races, for the existence of intermediates is one of the distinguishing characters of the race: if there are no intermediates, there are no races.

Dwight Ingle, the distinguished professor of physiology at the University of Chicago and former editor of Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, once referred to such claims as the fallacy of obscurantism:

It is argued that because no race is homogeneous and because the word “race” cannot be clearly defined, the word should be dropped from our vocabulary. Therefore, problems relating to the biology of race do not exist and should not be debated or investigated. Those who oppose the study of biological differences among races do not hesitate to study environmental causes of racial problems, or to recommend social actions based on racial identity rather than individuality. It is argued that “race” is a social concept, but even if this conclusion is accepted, there is no logical reason why groups defined in social terms cannot be studied for biological correlates of social differences.

Credible research findings across the full spectrum of the behavioral and life sciences fail to corroborate the claim that race is biologically insignificant. (It should be noted that a great deal of this evidence has turned up in new genetic technologies in the wake of the human genome findings.) Typically, an egalitarian critic will erect a straw-man argument — claiming there are no “pure races” or “absolute racial types” — hence taking a flying leap in logic to assert that race is, therefore, invalid. The argument that racial intermediates or interracial hybrids, what physical anthropologist Carleton S. Coon referred to as “clines,” demonstrate that race is a meaningless category simply fails to hold up under sustained empirical and logical scrutiny. One could easily recognize differences between distinct European physical traits in Caucasians — native descendants of Nordic Scandinavian countries — and the physical characteristics of other geographical populations in Africa, Asia, or Australia, most notably the Australian aborigine, native Nigerian, or East Asian in the Pacific Rim. Even though interracial crossings can yield mixed-race hybrids that in subsequent generations can often transcend these more racially distinct groups, the argument that absolute definitive racial types are necessary to establish the reality of race is, by any reasonable measure, a straw-man fallacy. In terms of population comparisons, statistical averages and gene frequencies in measured traits — from blood type and stature to personality, temperament, and IQ — are reliable indicators of racial differences.

Biological Foundations of Race

In his textbook, Principles of Human Genetics, the eminent University of California geneticist Curt Stern explains in lucid detail the genetics of race: “A race, then, is a group of individuals whose corporate genic content, called the gene pool, differs from that of other groups.” Races are in essence gene pools or breeding populations. On one level, racial variation reflects differences in allelic frequencies in ancestral populations. One explicit example of this is the racial distribution of the ABO blood group types, which the geneticist William Boyd pinpointed in his influential 1950 study. A. E. Mourant notes, “The outstanding feature of the blood group distribution in Negroes is the extremely high frequency of the Rh chromosome cDe (R°), which is consistently about 60 per cent or more as compared with about z per cent in Europeans and seldom, if ever, above 15 per cent in any non-Negro population except the Negritos of Malaya.” Stanley M. Garn puts the racial distribution of blood groups into perspective:

For many centuries the possibility of transfusing blood has appealed to surgeons. Great numbers of men die from loss of blood following accidents or battle. Patients expired during and following operations, patients who could have been saved by blood transfusion. But until 1900 transfusions were impractical: too often they ended in shock and death. Somehow blood just didn’t mix.

Arthur Jensen provides a summary of the meaning of race, explaining the genetics of racial variation, in his detailed analysis of the causes of population differences in The g Factor.

Racial differences are a product of the evolutionary process working on the human genome, which consists of about 100,000 polymorphic genes (that is, genes that contribute to genetic variation among members of a species) located in the twenty-three pairs of chromosomes that exist in every cell of the human body. The genes, each with its own locus (position) on a particular chromosome, contain all of the chemical information needed to create an organism. In addition to the polymorphic genes, there are also a great many other genes that are not polymorphic (that is, are the same in all individuals in the species) and hence do not contribute to the normal range of human variation.

Likewise, Rushton and Baker offer meticulously thorough assessments of race as a viable biological construct, providing an array of quantitative and qualitative evidence from a variety of sources. Rushton, in particular, puts forth one of the most comprehensive reviews of racial differences in the scientific literature — an analysis which spans the full scope of anatomical as well as psychological differences. His relative ranking of races by diverse variables reveals a consistent three-way pattern between Mongoloid, Caucasoid, and Negroid averages in brain size, intelligence, maturation rate, personality, social organization, and reproduction strategy. Rushton’s life history and genetic similarity thesis puts a wealth of statistical data into context, which offers a comprehensive evolutionary explanation for racial differences.

Across time, country, and circumstance, African descended people show similarities that differentiate them from Caucasoids who, in turn, show similarities differentiating them from Orientals. Although variation occurs from country to country, consistency is found within racial groups with Chinese, Koreans, and Japanese being similar to each other and different from Israelis, Swedes, and American whites, who, in turn, are similar to each other but are different from Kenyans, Nigerians, and American blacks…. Mongoloids and Caucasoids have the largest brains, the slowest rate of dental development, and produce the fewest gametes. No environmental factor is known to cause an inverse relation between brain size and gamete production nor cause so many diverse variables to cohere in so comprehensive a fashion. There is, however, a genetic factor: evolution.

In a more recent study, Rushton found additional evidence for racial differences in brain size and IQ from musculoskeletal traits — some 37 morphological cranial and post-cranial traits. The authors show beyond reasonable evidentiary standards that brain size is correlated with average IQ scores and that a range of morphological traits — from cranial size, shape, and length to neck, pelvic, and lower limb traits — and physical measurements correspond to measurable racial patterns in brain size and IQ differences.

Races also differ in terms of genetic polymorphisms. Clusters of small DNA sequences, known as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), have been used to identify differences — with genetic markers — in at least five geographical races. The New York Times science reporter Nicholas Wade explains how geneticists refined SNP research: “As the human genome was decoded, geneticists started looking for single bases that differed from the usual base at that position on the chromosome. These single base changes, called SNPs or ‘snips,’ serve as markers to track variant genes, and can themselves be the cause of the variation.” In the post-human genome era, researchers have carved out specialized sub-fields at the molecular and cellular level known as genomics and proteomics. Microbiologists have been using this new approach for identifying the protein structure and chemical configuration that can trigger certain diseases, such as diabetes, colon cancer, high blood pressure, prostate cancer, and asthma. In particular, researchers have employed a specific new strategy, “mapping by admixture linkage disequilibrium” (MALD), for screening 2,000 genetic markers “instead of the 2,000,000 that must be used in traditional linkage analysis. . . What is needed to use this approach, however, is an exquisite map of very special genetic markers that exhibit substantial differences between two races.”

Major research initiatives are under way by pharmaceutical and private biotech firms to unravel the genetic mysteries behind the differential rates of infection for debilitating and life-threatening diseases, to which some racial and ethnic groups are more predisposed than other sub-populations. One example is the disclosure that some prescribed heart medications work poorly in blacks. Enalapril, or the ACE inhibitor Vasotec, “reduced the risk of hospitalization 44 percent among whites with damage to their ventricles. There was no significant reduction among similar black patients.” While rates of prostate cancer differ between Caucasian and African-American males, the conventional explanation that Caucasian men seek out and receive better and more timely treatment is being challenged by researchers who are investigating molecular differences to find out if the adhesion molecule E-cadherin and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP 2 and 9) molecules explain the rates of aggressive prostate cancer in African-American men. Scientists conducting the “world’s first large-scale trial of an AIDS vaccine” discovered some unlikely results: race differences in the reduction of AIDS infection rates in the use of AIDVAX, a new AIDS vaccine. Although the vaccine failed to reduce the overall AIDS infection rates during a three-year trial, “the vaccine appeared to reduce infection rates. . . among blacks and Asians and other non-Latino minorities. . . by two-thirds. Among a group of 314 black volunteers, the vaccine appeared to cut infections by 78 percent.” Researchers at the University of Cincinnati reported in the New England Journal of Medicine the results of a study that found a “combination of two pairs of genes rarely found in whites increases the risk of congestive heart failure in blacks and plays a role in one-quarter of cases of the disease diagnosed among blacks. . .” While researchers have tracked ethnically unique diseases, such as sickle-cell anemia in blacks and Tay-Sachs in Jews, and a greater range of information exists about the distinctive nature of these population-based diseases, a number of other debilitating diseases that disproportionately affect other ethnic groups at greater infection rates are being widely analyzed for their unique genetic structure.

One of the arguments used to contest the concept of race minimizes the degree to which genes or gene frequencies distinguish one race from another. This is one of the biggest shams used to support the view that races are genetically indistinguishable. Egalitarians often reiterate the claim that 99.9 percent of human genes are racially shared among Homo sapiens. These genes are in essence present in individuals across racial boundaries. Moreover, it is often argued that no race has genes that are racially unique. We are often told that, with the exception of a handful of genes that are directly tied to skin color, races are virtually identical genetically. However, it has been demonstrated that approximately 50 genes or genetic mutations separate humans from primates, and the recent decoding of the mouse genome “estimates that less than 2 percent of mice genes lack human counterparts.” The genetic similarities between mice and men are chemically nearly exact, but a few selected genetic switches that turn certain genes on within human and mouse genomes yield the difference between a Beethoven and a rodent. The argument that race differences are so genetically minor as to be nearly indistinguishable in microbiological terms is a non sequitur. Race differences by their very nature stem from minor biological distinctions. The threshold for establishing polygenic markers between racial groups is not dependent upon identifying sizable genetic race differences.

The degree of disingenuous claims about the so-called specious nature of racial classifications arguably reached its peak during the waning days of the Clinton administration. Dr. Francis Collins, J. Craig Venter, Clinton and, via satellite, British Prime Minister Tony Blair appeared at a joint press conference in late June 2000 to announce the first crudely completed map of the human genome. During the press conference, Venter, a pioneer in the field of genomic studies, alongside Collins, head of the Human Genome Project, claimed that the “concept of race has no genetic or scientific basis.” Venter claimed that the results of the Human Genome Project failed to distinguish populations along conventional racial classifications; races are simply nonexistent in genetic terms. He is on record stating that no serious scholar within the genomic field considers race to be a scientific concept. Three months after celebrating this unprecedented milestone in the history of human genetics, Celera Genomics, Venter’s biotech company, announced that it had “identified more than 2 million of the subtle genetic differences that underlie the diversity of the human race and compiled them into a database for use by its research customers.” The database of SNPs (genetic population markers), then the most comprehensive database available to researchers, was based upon the “sequencing of five ethnically diverse donors.” A Seattle Times article in February 2001, which identified the ethnic breakdown of the five Celera donors as being Hispanic, Asian, Caucasian and African American, quotes Venter as saying, presumably with a straight face, “in the five genomes, there is no way to tell one ethnicity from another. . . Society and medicine treat us all as members of populations, where as individuals we are all unique and population statistics do not apply.”

Questions abound: Why would the biotech firm of a pioneering researcher in human genomics seek to establish “2.4 million unique, proprietary” genetic population markers from DNA samples of five ethnically diverse donors if the president of the firm claims that race and ethnicity are genetically meaningless categories? If these ethnic donors are indistinguishable from one another, why sample their DNA as representatives of specific ethnic types? How could these DNA samples yield specific genetic markers that are unique to each ethnic group if conventional racial and ethnic classifications are genetically meaningless? If race and ethnicity are truly useless biological entities, why not solicit DNA samples randomly regardless of race or ethnicity? Why would a company like Celera seek out this sort of information and pursue this level or research if race and ethnicity were as irrelevant as Celera’s president claimed? If race and ethnicity are merely “social constructs” why would it matter to search for patterns of protein synthesis unique to the solicited donors from these specific ethnicities ? Why bother? In conducting this level of research, in which DNA “profiles” are compiled in a database for further biomedical analysis, why is population “diversity” an important aspect of DNA profiling? Or is there more to the story of race that lies behind this semantic charade?

One of the more interesting developments in the use of DNA technology to decipher racial differences is the turn of events that marked the manhunt for a serial killer in Louisiana. Police and FBI agents had used conventional profiling methods (non DNA) in their search for a criminal suspect. The profile was that of a 25- to 35-year-old white male. After samples of 1,000 white men were taken and tested, authorities were no closer to resolving the case after months of investing contradictory eyewitness leads. The break in the case occurred when a Sarasota, Florida, company, DNAPrint Genomics Inc., “indicated the man they sought in the murders of at least five women was 85 percent African and 15 percent American Indian.” The information provided a new lead in the case and the subsequent arrest of a suspect, Derrick Todd Lee, a few days later. Pennsylvania State University geneticist Mark Shriver developed the SNP-based forensic test that looks for “ancestry informative markers,” which the Sarasota-based lab used to identify the ethnic profile of the suspect. The 34-year-old suspect under arrest had a “highly unusual genetic marker” according to some media reports. It was reported to be the first instance in which DNA analysis was used to determine the physical characteristics and racial background of a criminal suspect.

Authorities in the case seemed to downplay the significance of this scientific breakthrough in narrowing the suspect’s physical appearance, but the use of emerging methods to isolate strands of DNA in sorting out population or racial traits by forensic lab technicians provided critical clues that shifted the focus of the investigation. How could this possibly occur if, as Venter and others claim, researchers are unable to distinguish racial or ethnic differences via genetic markers? Forensic anthropologists “can often determine a dead person’s sex, race, height, approximate age and time of death. . . from a single thigh bone. . .” and in some cases researchers can determine a suspect’s race by tooth structure, according to Dr. Bernard A. Levy, chief forensic dentist and an oral pathologist at the University of Maryland at Baltimore. “Generally, females have finer bone structure and smaller bones than males. . . the actual shape of the jaws varies from race to race, and some have different shapes of certain teeth.” How could a forensic anthropologist make this determination about race by comparing different skeletal and physical attributes if race is strictly a “social construct”?

Prior to the Louisiana case, police in Britain employed “DNA profiling” to determine the race of criminal suspects by analyzing blood, hair color, and other physical attributes from evidence collected at crime scenes. According to the Sunday Times of London, “In one test, police used the technique to predict the ethnic origin of 109 offenders and 105 were correct.” The technique is capable of determining “the five main ethnic groups suspects are likely to come from, including oriental, Afro-Caribbean, Caucasian, Indo-Pakistani or Middle Eastern.” Crude tests conducted in May 1998 by the London-based Forensic Science Service and South Yorkshire police, two years before the celebrated preliminary findings of the Human Genome study, using samples of DNA and saliva, made it “possible to predict race with about 98 percent accuracy.” Accordingly, the “prediction [is] based on the bar codes that make up a DNA profile. Some are common to all ethnic groups, but some are found almost exclusively in one race.” In fact as early as 1993, a British forensic scientist devised an early DNA test that was able to identify the ethnic background of suspects in unsolved crime cases. The test was able to “distinguish between ‘Caucasians’ and ‘Afro-Caribbeans’ in 85 percent of cases.”

For all the claims that a concept such as race is so biologically dubious, there are several interesting research developments, some of which have occurred in the past two years and some of which are ongoing projects. Here are but a few examples:

- Researchers are now capable of identifying patterns of genetic markers in order to detect an individual’s “geographical ancestry” (race) and tracing the ancestral lineage to the point of origin. Computer analysts are able to sift through genetic patterns of “160 places in human DNA” and pinpoint which DNA samples originated in Europe, East Asia, or Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Howard University has launched what is estimated to be the “largest repository of DNA from African Americans” for use in biomedical research. “The samples [are to] be used to find genes involved in diseases with particularly high rates among blacks like hypertension and diabetes.”

- A new experimental drug to treat blacks for heart failure called BiDil is in the developmental phase of research by a Bedford, Massachusetts, biomedical firm called NitroMed Inc. The company “has launched a study in 1,100 patients to follow up on prior research that indicated the drug works best in blacks.”

- African Ancestry, a Washington-based firm launched by Howard University microbiologist Rick Kittles, offers African Americans the chance to trace their ancestral roots. “Kittles. . . has compiled a database of DNA samples collected from 82 West and Central African populations, from Madagascar to Liberia.” Similar programs, such as Boston University’s African-American DNA Roots Project and Howard University’s African Burial Ground Project, assists blacks in tracing the origin of their African heritage by using genetic markers in genealogical research.

- Scientists at the University of Alabama are using a federally funded study to probe the genetic background of “1,300 black Americans with schizophrenia and 5,000 relatives to look for genes that predispose people to the disease.” According to Rodney Go, a leading University of Alabama researcher on the project, the study “focuses on American blacks because the unusually wide diversity in their DNA should make locating genes easier.”

- DeCODE, an Icelandic biomedical research firm, is under contract by the Icelandic government to analyze the health records and genetic data of Iceland’s 270,000 citizens for disease risks. “Already, the company says it has mapped or identified genes involved in arthritis, stroke, schizophrenia, and many other diseases and it is beginning to publish these findings.” Similar population studies are under way in the United Kingdom, Sweden, Latvia, and Estonia.

Neil Risch, a geneticist at Stanford University, has been an outspoken defender of using race and ethnic categories for biomedical and genetic research. In a major paper published in Genome Biology, Risch and a team of researchers outlined the case for race-based classifications:

A clearer picture of human evolution has emerged from numerous studies over the past decade using a variety of genetic markers and involving indigenous populations from around the world. In summary, populations outside Africa derive from one or more migration events out of Africa within the last 100,000 years. The greatest genetic variation occurs within Africans, with variation outside Africa representing either a subset of African diversity or newly arisen variants. Genetic differentiation between individuals depends on the degree and duration of separation of their ancestors. Geographic isolation and in-breeding (endogamy) due to social and/or cultural forces over extended time periods create and enhance genetic differentiation, while migration and intermating reduce it. . .

Most recently, Wilson et al. studied 354 individuals from eight populations deriving from Africa (Bantus, Afro-Caribbeans and Ethiopians), Europe/Mideast (Norwegians, Ashkenazi Jews and Armenians), Asia (Chinese) and Pacific Islands (Papua New Guineans). Their study was based on cluster analysis using 39 microsatellite loci. Consistent with previous studies, they obtained evidence of four clusters representing the major continental (racial) divisions described above as African, Caucasian, Asian, and Pacific Islander. . .

Are racial differences merely cosmetic?

Two arguments against racial categorization as defined above are firstly that race has no biological basis, and secondly that there are racial differences but they are merely cosmetic, reflecting superficial characteristics such as skin color and facial features that involve a very small number of genetic loci that were selected historically; these superficial differences do not reflect any additional genetic distinctiveness. A response to the first of these points depends on the definition of ‘biological.’ If biological is defined as genetic then, as detailed above, a decade or more of population genetics research has documented genetic, and therefore biological, differentiation among the races. This conclusion was most recently reinforced by the analysis of Wilson et al. If biological is defined by susceptibility to, and natural history of, a chronic disease, then again numerous studies over past decades have documented biological differences among the races. In this context, it is difficult to imagine that such differences are not meaningful. Indeed, it is difficult to conceive of a definition of ‘biological’ that does not lead to racial differentiation, except perhaps one as extreme as speciation.

The authors point out that “risk factors” that put some people at a greater risk for certain diseases often have a differential impact based upon race or ethnic ancestry. In an impressive display of data, the authors compare “genetic clusters” to “racial groups” by allele frequency differentiation of drug metabolizing enzymes. Another detailed study published in Science magazine analyzed “human population structure using genotypes at 377 autosomal microsatellite loci in 1056 individuals from 52 populations.” Most of the genetic variation (93-95 percent) among individuals accounted for within-population differences, and differences among major groups constitute only 3 to 5 percent of the genetic variation. “Nevertheless, without using prior information about the origins of individuals, we identified six main genetic clusters, five of which correspond to major geographic regions, and subclusters that often correspond to individual populations.” This particular study, one of the most comprehensive in scope and size, showed again that “[t]he structure of human populations is relevant in various epidemiological contexts. As a result of variation in frequencies of both genetic and non-genetic risk factors, rates of disease and of such phenotypes as adverse drug response vary across populations.” A recent cover story in Scientific American, a publication not widely known to be sympathetic to behavior genetic research or one that has a history of pointing to the validity of race differences, raised the question: “Does Race Exist?” The authors of the article, Michael J. Bamshad and Steve E. Olson, reach similar conclusions to the findings above: “Some groups do differ genetically from others, but how groups are divided depends on which genes are examined. . . In other words, individuals from different populations are, on average, just slightly more different from one another than are individuals from the same population. Human populations are very similar, but they often can be distinguished.”

In light of these recent developments that substantiate the biological reality of race, the Public Broadcasting System in April 2003 broadcast a three-part series on race produced by California Newsreel titled “Race: The Power of an Illusion.” The program offered viewers a thoroughly distorted and dishonest perspective of race that showed on-camera interviews with Marxist-oriented scholars in various academic fields. The only academics that were consulted as authorities on race are well known for their extreme egalitarian biases, such as Richard Lewontin, Joseph Graves, Stephen Jay Gould, Alan Goodman, and Audrey Smedley. No attempt was made to offer a counter-viewpoint from leading researchers in any relevant field of study that could have provided an alternate perspective on the biology of race. The producer’s website describes the “documentary” in the following terms:

What is this thing we call ‘race’? Can race be found in biology or did we make the whole thing up ? And if so, why? “Race — The Power of an Illusion” is a provocative new series broadcast by PBS that challenges one of our most fundamental beliefs: that human beings come bundled into three or four distinct groups. It scrutinizes the implications of looking at race as a biological fallacy but a social reality.

The New York Times found the series offered “viewers a racially diverse selection of like-minded experts” and noted, “There is no discussion, let alone lively debate, about the issues confronting our society, from college affirmative-action admissions policies to racial profiling. Instead, it is a history lesson about economic and social injustice that PBS has told well, many times, and with much of the same source material.” The executive producer of the series and co-director of California Newsreel, Larry Adelman, appeared on Tavis Smiley’s National Public Radio program on April 29, 2003, and when asked about the “provocative way” of creating a program around the question, “What is race?” Adelman responded,

Well, you know, if you go out and ask 10 people in the street, ‘What is race?’ I bet you will find 10 different answers. We all think we’re experts on race, but the fact of the matter is, when you start talking about it, our assumptions start quickly falling apart. How many races would there be? Who decides? What are the criteria between them? Are there three, four, five, 55? I mean, we all assume that race, just like rain falls down and the chair has four legs, that the world’s peoples come divided somehow biologically into three or four or five different groups.

Amazingly enough, Adelman managed to find more than one academic “authority” who could tell him what he wanted to hear: there are no such things as biological races. One of the major arguments the show emphasized in attempting to show how race is an “illusion” is that “there isn’t a single characteristic, trait — or even one gene — that can be used to distinguish all members of one race from all members of another” race. Again, this is simply a straightforward fallacy: the expression of genes, particularly among polygenic traits, is typically not the exclusive domain of any singular gene. Racial differences can occur between gene frequencies on loci of allelic markers for different DNA sequences. In fact, the very nature of allelic frequencies is defined as “the percentage of all alleles at a given locus in a population gene pool represented by a particular allele.” As Michael Rienzi pointed out in a review of the program, “the idea that a race must be characterized by specific genes found only in that race and never in another race is a straw man put up by experts, so they can knock it down and make politically-motivated claims. . . Real scientists understand that racial differences are a result of many patterns of differences in gene frequencies, as well as specific differences in forms of various genes that code for racially-relevant physical traits.”

Another fallacy and disingenuous claim on the part of the program’s producers begins with a statement made by Alan Goodman, a biological anthropologist: “Human biological variation is so complex. There is [sic] so many aspects of human variation. So there are many, many ways to begin to explain them.” The presumption in this remark is that human variation is too biologically complex for race to be a valid biological category. Hence, there are many ways to unravel the intricately complex mysteries of “human biological variation,” but race isn’t one of them. Here the narrator magnifies what is a major logical inconsistency in the program’s lynchpin argument: genetically based racial traits.

NARRATOR: Variation in some traits, like eye shape, hair texture, whether or not your tongue curls, involves very few genes. And even those genes haven’t all been identified…. Variation in traits we regard as socially important is much more complicated. Differences in how our brains work, how we make art, how gracefully we move. . . Genes may contribute to variation in these traits, but to the extent they do, there would be a cascade of genes at work, interacting with each other and the environment, in relationships so intricate and complex, that science has hardly begun to decipher them.

This is simply an attempt to reason backwards from a foregone conclusion: When it comes to race and racial differences, no single gene is unique to any single race even though for other comparable variations in physical traits (e.g. hair color, eye shape, hair texture, etc.) “those genes haven’t all been identified.” If some genes haven’t been identified for these physical traits, which correlate with conventional taxonomic classifications of race, then why are the producers so certain that no single gene differentiates one race from another race? Baker once addressed this very fallacy of racial denial:

The principal characters that distinguish typical members of different races of man from one another are mostly controlled by “polygenes”; that is to say, by the combined action of many genes having small but cumulative effects. An enormous number of examples could be given. For instance, the length of the forearm in relation to that of the upper arm is considerably greater in Negrids than in Europids; and the breadth of the skull in relation to its length is much less in Australids (Australian aborigines) than in Mongolids. Such features as these are controlled by polygenes. It is very difficult to analyze polygenes genetically, because the effect of each is too small to be observed separately. . . It is an unfortunate fact that the concentration of attention on genes that can be analyzed genetically has resulted in loss of interest in those characters, controlled by polygenes, that make it possible to distinguish a particular person of one race from particular persons of other races. The proper course is to use these primary distinguishing characters in the classification of mankind; only then, after the races and subraces have been recognized, is one in a position to study effectively the frequencies of those single genes that can be traced separately from generation to generation, and which occur in all or most races but more abundantly in some than in others.

Another fallacy in this line of reasoning is that genes that could be plausibly identified with racial variation would be easy to decipher and would represent simple Mendelian structures, whereas genes involved in other trait variations would involve a “cascade” of genes and genetic patterns in a complex level of interaction. The political motivations and ideological agenda of the producers of “Race — The Power of an Illusion” are transparent: The advancement of an egalitarian racial agenda that rejects the idea of race and racial biological differences. In fact the California Newsreel website contains pervasive references to “social justice” advocacy, including a hagiographic tribute to Ousmane Sembene, an African cinematographer and author who joined the French Communist Party in 1950 and supported the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN).

Biosociology of Race: The Question of Racial Character

Generally, disputes over the significance of race in the behavioral, social, and biomedical sciences stem from a failure to conceptualize the contribution of racial differences among a constellation of biosocial variables, especially when assessing the relative input of genetic and environmental (nonbiological) attributes for any given trait that is distributed across populations. As noted earlier, the assumption that egalitarians repeatedly make is that racial disparities are explained exclusively by environmental forces. Differences in average income levels, IQ scores, educational attainment, national levels of wealth and GDP, poverty, out-of-wedlock births, rates of HIV infection, violent crime, and incarceration rates are viewed by egalitarians as having no known biological origin or racial correlation. Typically, disparities in educational outcomes, violent crime, or competitive executive-level corporate positions are considered to be the result of unequal opportunities or a disadvantaged background instead of measurable biosocial traits such as intelligence, temperament, personality, anxiety, or aggression levels.

The reality of race becomes apparent in the daily experiences of community life — neighborhoods that differ substantially in terms of racial demographics. From a comparative vantage point, behavioral and social norms are more easily recognized between predominantly black and Hispanic communities within urban areas and the largely white suburban neighborhoods and towns in more rural districts. Consider the annual Morgan Quinto rankings for America’s “safest” and “most dangerous” cities: One of the single most distinguishing factors between the top ten safest and most dangerous cities (overall rankings) is the racial demographic composition of the city. The safest cities have largely non-Hispanic white populations that are well above the national average (80 percent or higher) and the most dangerous cities have majority black populations (50 percent or higher). These findings fit what the late Glayde Whitney, a behavior geneticist and professor of psychology at Florida State University, found in a scatter-plot diagram of the correlation between murder rate and percentage of the population that is black. The correlation is S = +0.77.