The Racial Revolution: Race and Racial Consciousness in American History

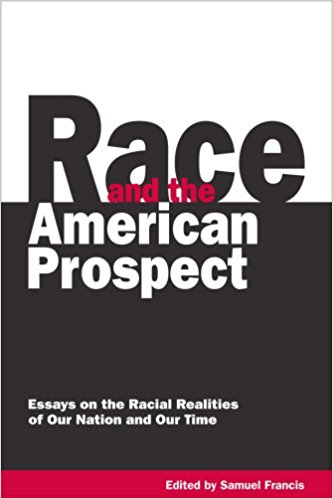

Jared Taylor, Race and the American Prospect, 2006

It is not often that societies go through changes in thinking so profound as to deserve the name “revolution.” Rarely are basic assumptions stood on their heads. Occasionally, as when Islam swept through North Africa, mass religious conversion brings about radical change. Even rarer are secular movements, like Marxism, that transform societies. Though most Americans are not conscious of it, the United States has undergone just such a radical change — and only in the last forty or fifty years. It is a change that is meant to touch every part of our lives and continues to transform the very population of our country. It is the revolution in how we think about race.

To the extent they consider the past at all, most Americans believe that racial equality, integration, and multiculturalism flow naturally from the republican, anti-monarchical principles of the American Revolution. They may be aware that Thomas Jefferson owned slaves, but they persuade themselves that the man who wrote “all men are created equal” had a distant vision of the egalitarian, heterogeneous society in which we live today. They are wrong. Current assumptions about race are a complete reversal of the views of not only the Founders but of the great majority of Americans up until the 1950s and 1960s. Our country has experienced a true revolution, one in which what was once a horror to be avoided at all costs is now proposed as the path to salvation. Change on this scale is rare in any society.

Because current views of race are so heavy with moral baggage, our country faces a strange dilemma: Practically every hero of American history was, by today’s standards, a moral inferior. Any man who would today profess the views of Thomas Jefferson or Abraham Lincoln would be considered not merely wrong but unfit to hold the most minor office of public trust. Americans generally ignore or sanitize the now embarrassing views of the very men who epitomize American greatness. To do otherwise, to encounter the frank opinions of earlier generations, is to find themselves morally at war with their own past.

Signing the Declaration of Independence.

In the pages that follow, many distinguished Americans will speak for themselves, but it is possible to summarize the views that prevailed in this country until a few decades ago. Americans believed that race was a fundamental aspect of individual and group identity. They believed people of different races differed in temperament and ability, and that whites built societies superior to those of non-whites. They took it for granted that America must be peopled with Europeans and that European civilization could not be maintained without Europeans. Many saw the presence of non-whites in the United States as a terrible affliction, and believed that if non-whites could not be removed from the country entirely they should be separated from whites socially and politically. Americans were unalterably opposed to miscegenation, which they called “amalgamation.” They considered it an unnatural, even disgusting dilution of the unique characteristics of whites.

Jefferson and His Contemporaries

Among the founders, Thomas Jefferson wrote about race at greatest length. He thought blacks were mentally inferior to whites, and though he hoped slavery would be abolished, he did not want free blacks to remain in America: “When freed, [the Negro] is to be removed from beyond the reach of mixture.” Jefferson was, therefore, one of the first and most influential advocates of “colonization,” or sending blacks back to Africa.

He also believed in the destiny of whites as a racially conscious people. In 1786 he wrote, “Our Confederacy [the United States] must be viewed as the nest from which all America, North and South, is to be peopled.” In 1801 he looked forward to the day “when our rapid multiplication will expand itself. . . over the whole northern, if not the southern continent, with a people speaking the same language, governed in similar forms, and by similar laws; nor can we contemplate with satisfaction either blot or mixture on that surface.”

Jefferson was deeply conscious of the western direction in which Anglo-Saxons had moved, first from the Germanic homeland to England, on to the colonies, and thence, he hoped, to people the Americas. He studied the origins of the Saxons and learned that they were said to have originated in the Cimbric Chersonesus of Jutland. When he proposed an ordinance to create new states in the Mississippi valley, he looked backward to his racial origins in proposing the name Chersonesus for the area between Lakes Huron and Michigan. This was not a new American name but one that harked back to Jefferson’s own Germanic origins.

Jefferson was himself far too liberal in the eyes of many, who were suspicious of the implications of the “all men are created equal” phrase of the Declaration, and the Federalists attacked him repeatedly for egalitarian leanings. Below is an excerpt from an 1802 poem by a fictional Jefferson slave named Quashee that appeared in a Federalist weekly called the Port Folio, published by Jefferson’s political enemies. It captures a contemporary view of Jefferson as a dangerous radical — a view that has almost completely disappeared from current thinking:

Our massa Jeffeson he say,

Dat all mans free alike are born:

Den tell me, why should Quashee stay,

To tend de cow and hoe de corn?

Huzza for massa Jeffeson.

And why should one hab de white wife,

And me hab only Quangeroo?

Me no see reason for me life!

No. Quashee hab de white wife too.

Huzza for massa Jeffeson.

Benjamin Franklin wrote little about race, but clearly had a sense of racial loyalty. “[T]he Number of purely white People in the World is proportionably very small,” he once observed. “I could wish their Numbers were increased.”

James Madison, like Jefferson, believed the only solution to the problem of racial friction was to free the slaves and send them away. He proposed that the federal government sell off public lands in order to raise the huge sums necessary to buy the entire black population and transport it overseas. He favored a constitutional amendment to establish a colonization society to be run by the president. After his two terms in office, Madison served as president of the American Colonization Society, to which he devoted much time and energy.

The objective of the society was to return blacks to Africa. As Henry Clay said, at the society’s inaugural meeting in 1816, it hoped to “rid our country of a useless and pernicious, if not dangerous portion of the population.” The following prominent Americans were not merely members but served as officers of the society: Andrew Jackson, Daniel Webster, Stephen Douglas, William Seward, Francis Scott Key, Gen. Winfield Scott, and two chief justices of the Supreme Court, John Marshall and Roger Taney. All believed that the presence of blacks was a menace and that expatriation was the only long-term solution. James Monroe was such an ardent champion of colonization that the capital of Liberia is named Monrovia in gratitude for his efforts.

As for Roger Taney, as chief justice he penned in the Dred Scott decision of 1857, what may be the harshest official federal government pronouncement on the status of blacks ever written: “Negroes are beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the White race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior that they have no rights which a White man is bound to respect.”

Abraham Lincoln considered blacks to be — in his words — “a troublesome presence” in the United States. During the Lincoln-Douglas debates he expressed himself unambiguously:

I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will for ever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be a position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.

His opponent, Stephen Douglas, was even more outspoken, and made his position clear in the very first debate:

For one, I am opposed to negro citizenship in any form. [Cheers — Times] I believe that this government was made on the white basis. [‘Good,’ — Times] I believe it was made by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity forever, and I am in favor of confining the citizenship to white men — men of European birth and European descent, instead of conferring it upon negroes and Indians, and other inferior races. [‘Good for you. Douglas forever.’ — Times]

It is worth noting that Douglas, who took the more firmly anti-black view, won the election.

After Lincoln became president he campaigned steadily for colonization, and even in the midst of war with the Confederacy found time to work on the problem, appointing Rev. James Mitchell as Commissioner of Emigration. He invited a group of blacks to the White House to try to persuade them to leave the country. In a meeting on August 14, 1862, he told them, “There is an unwillingness on the part of our people, harsh as it may be, for you free colored people to remain with us.” He explained that he had learned of a promising colonization site in Central America to which he urged them to take all of their race. It is ironic that the “Great Emancipator,” as he would later be called, was the first president to invite a delegation of blacks to the White House to discuss a policy matter — to ask them to leave the country. Later that year, in a message to Congress, he went even further and argued for the forcible removal of free blacks.

States that entered the union in the years leading up to the Civil War were determined to avoid the race problem entirely. The people of Oregon territory voted not to permit slavery, but voted in even greater numbers not to let blacks set foot in the state at all. In language that survived until 2002, Oregon’s 1857 constitution provided that “[n]o free negro, or mulatto, not residing in this state at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall come, reside, or be within this State, or hold any real estate.”

Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, shared anti-black sentiments: “This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men. . . ” Like Jefferson, he thought whites had a clear destiny: “This whole vast continent is destined to fall under the control of the Anglo-Saxon race — the governing and self-governing race.”

Before he became president, James Garfield wrote, “[I have] a strong feeling of repugnance when I think of the negro being made our political equal and I would be glad if they could be colonized, sent to heaven, or got rid of in any decent way. . . ”

What of twentieth century presidents? Theodore Roosevelt thought blacks were “a perfectly stupid race,’ and blamed Southerners for bringing them to America. In 1901 he wrote: “I have not been able to think out any solution to the terrible problem offered by the presence of the Negro on this continent. . . he is here and can neither be killed nor driven away. . . ” As for Indians, he once said, “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn’t inquire too closely into the health of the tenth.”

William Howard Taft once told a group of black college students, “Your race is adapted to be a race of farmers, first, last and for all times.”

Woodrow Wilson was a confirmed segregationist and as president of Princeton prevented blacks from enrolling. He enforced segregation in government offices and was supported in this by Charles Eliot, president of Harvard, who argued that “civilized white men” could not be expected to work with “barbarous black men.” During the presidential campaign of 1912, Wilson took a strong position in favor of excluding Asians: “I stand for the national policy of exclusion. . . We cannot make a homogeneous population of a people who do not blend with the Caucasian race. . . Oriental coolieism will give us another race problem to solve and surely we have had our lesson.”

Warren Harding’s views were little different: “Men of both races may well stand uncompromisingly against every suggestion of social equality. This is not a question of social equality, but a question of recognizing a fundamental, eternal, inescapable difference. Racial amalgamation there cannot be.”

Henry Cabot Lodge took the view that “there is a limit to the capacity of any race for assimilating and elevating an inferior race, and when you begin to pour in unlimited numbers of people of alien or lower races of less social efficiency and less moral force, you are running the most frightful risk that any people can run.”

Congressman William N. Vaile of Colorado was a prominent supporter of the 1924 immigration legislation that was designed to keep the country white. He explained his reasons for opposing immigration from non-European sources:

Nordics need not be vain about their own qualifications. It well behooves them to be humble. What we do claim is that the northern European, and particularly Anglo-Saxons made this country. Oh yes, the others helped. But that is the full statement of the case. They came to this country because it was already made as an Anglo-Saxon commonwealth. They added to it, they often enriched it, but they did not make it, and they have not yet greatly changed it. We are determined that they shall not. It is a good country. It suits us. And what we assert is that we are not going to surrender it to somebody else or allow other people, no matter what their merits, to make it something different. If there is any changing to be done, we will do it ourselves.

In 1921, Vice President-elect Calvin Coolidge wrote in Good Housekeeping about the basis for sound immigration policy: “There are racial considerations too grave to be brushed aside for any sentimental reasons. Biological laws tell us that certain divergent people will not mix or blend. . . Quality of mind and body suggests that observance of ethnic law is as great a necessity to a nation as immigration law.”

Harry Truman is remembered for having integrated the armed services by executive order. Yet, in his private correspondence he was as much a separatist as Jefferson: “I am strongly of the opinion Negroes ought to be in Africa, yellow men in Asia and white men in Europe and America.” In a letter to his daughter he described waiters at the White House as “an army of coons.”

As recent a president as Dwight Eisenhower argued that although it might be necessary to grant blacks certain political rights, this did not mean social equality “or that a Negro should court my daughter.” It is only with John Kennedy that we finally find a president whose public pronouncements on race begin to be acceptable by today’s standards.

Even socialists, labor leaders, and “progressives” had a firm consciousness of race. William Jennings Bryan, for example, was certainly no reactionary, but he believed blacks should be prevented from voting “on the ground that civilization has a right to preserve itself.” At the 1924 Democratic convention he spoke strongly against a motion to condemn the Ku Klux Klan, and helped defeat it. His Populist Party running mate in 1886, Tom Watson, went even further, calling blacks a “hideous, ominous, national menace.” In 1908 Watson ran for public office with a platform he described as “standing squarely for white supremacy.” “Lynch law is a good sign,” he wrote. “It shows that a sense of justice yet lives among the people.” When he died in 1924 the leader of the American Socialist Party, Eugene Debs wrote, “he was a great man, a heroic soul who fought for power over evil his whole life long in the interest of the common people, and they loved and honored him.”

Ordinary working people, certainly as represented by the Socialist Party, were not liberal about race. The Socialists reached the height of their power during the early part of the twentieth century and at one time could claim two thousand elected officials. The party was split on the Negro question, but the anti-black faction was the stronger. The party organ, Social Democratic Herald, wrote on September 14, 1901, that blacks were inferior, depraved degenerates who went “around raping women (and) children.” The socialist press dismissed any white woman who consorted with blacks as “depraved.”

In 1903, the (Marxist) Second International criticized American Socialists for not speaking out against lynching and other violence against blacks. The Socialist National Quorum explained that Americans were silent on the subject because only the abolition of capitalism and the triumph of socialism could prevent the further procreation of black “lynchable human degenerates.” At the 1910 Socialist Party Congress, the Committee on Immigration called for the “unconditional exclusion” of Chinese and Japanese on the grounds that America already had problems enough dealing with Negroes. There was a strong view within the party that it was capitalism that forced the races to live and work together and that under socialism the race problem would be solved for good by complete segregation.

Samuel Gompers is probably the most famous labor leader in American history. He fought tirelessly for improvements in the lives of working people, but he was not a liberal on race. In a 1921 letter to the president of Haverford College explaining the American Federation of Labor’s position on immigration, he wrote:

We make no pretense that the exclusion of Chinese can be defended upon a high ideal, ethical ground, but we insist that it is our essential duty to maintain and preserve our physical condition and standard of life and civilization, and thus to assure us the opportunity for the development of our intellectual and moral character. Self preservation has always been regarded as the first law of nature. It is a principle and a necessity from which we ought not and must not depart.

Gompers concluded the letter with these words: “Those who believe in unrestricted immigration want this country Chinaized. But I firmly believe that there are too many right-thinking people in our country to permit such an evil.” He also wrote, “It must be clear to every thinking man and woman that while there is hardly a single reason for the admission of Asiatics, there are hundreds of good and strong reasons for their absolute exclusion.”

Literary figures reflected the thinking of their times. Ralph Waldo Emerson believed that “it is in the deep traits of race that the fortunes of nations are written.” Walt Whitman was a confirmed separatist: “Who believes that Whites and Blacks can ever amalgamate in America? Or who wishes it to happen? Nature has set an impassable seal against it. Besides, is not America for the Whites? And is it not better so?” Jack London was a well-known socialist, but he did not think socialism was universally applicable. It was, he wrote, “devised for the happiness of certain kindred races. It is devised so as to give more strength to these certain kindred favored races so that they may survive and inherit the earth to the extinction of the lesser, weaker races.” Mark Twain wrote of the American Indian that he was “a good, fair, desirable subject for extermination if ever there was one.” Henry Clay, likewise, during the time he was secretary of state, said there was never a “full-blooded Indian who took to civilization,” and that “their disappearance from the human family will be no great loss to the world.”

From its earliest days, laws established the racial basis of the republic. Indians were essentially outside the constitutional system: denied citizenship, untaxed, and not counted in the apportionment of representatives. As for blacks, Charles Pinckney of South Carolina, who was a member of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, stated that the Constitution was written for white men and that its protections were not intended for blacks, who he never expected would be recognized as citizens. The first naturalization law, passed in 1790, made citizenship available only to “free white persons.” Blacks were officially granted U.S. citizenship only in 1868 under the Fourteenth Amendment, but this did not apply to other races. In 1884, the Supreme Court officially determined that the Fourteenth Amendment did not confer citizenship on Indians associated with tribes.

State and federal laws explicitly excluded Asians from citizenship, and as late as 1914 the Supreme Court upheld the principle that citizenship could be denied to foreign-born Asians. The ban on immigration and naturalization of Chinese, established in 1882, continued until 1943. It was only when the United States found itself allied with China in the fight against Japan that Congress repealed the Chinese exclusion laws — but not by much. Congress set an annual Chinese immigration quota of 105 people. Needless to say, no immigration was permitted from Japan. American Indians did not receive blanket citizenship until an act of Congress in 1924.

The history of the franchise reflects a clear conception of the United States as a nation ruled by and for whites. Before the federal government took control of voting rights in the 1960s, the states determined who could and could not vote, and every state that entered the union between 1819 and the Civil War explicitly excluded blacks from the franchise. At an 1846 “people’s convention” in New York to consider the question, votes for blacks were voted down with the view that “nature revolted at the proposal.” In the Indiana constitutional convention of 1850 it was even proposed that any delegate who favored giving blacks the vote would himself be denied the franchise. In 1855, blacks could vote only in Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and Rhode Island, which states together accounted for only four percent of the nation’s black population. The federal government prohibited free Negroes from voting in the territories it controlled, and in the 1857 Dred Scott decision, the Supreme Court ruled that blacks, free or slave, could not be citizens of the United States, even though they might be citizens of a state.

The Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which prohibited withholding the franchise on racial grounds, was not an expression of egalitarianism so much as an attempt to punish the South — where most blacks lived — and a political calculation by Republicans that blacks would vote for their party. In the West, there was much opposition to the amendment for fear it would mean Asians could vote, and in Rhode Island ratification nearly failed for fear it would mean the Irish “race” would be allowed to vote.

Miscegenation

It is important to understand the deepest and most abiding reason for antipathy toward non-whites: revulsion for miscegenation. Since colonial times, the great fear of whites was that if blacks, in particular, were not held at a distance the result would be mixing that would debase the white race. It is only in this context that we can understand the abolitionist movement. Today the campaign to free the slaves is seen as a conscious step toward complete racial equality. In fact, many antebellum Americans favored abolition only if it were coupled with colonization to remove blacks “beyond the reach of mixture.” This was Jefferson’s and Lincoln’s view, and it was articulated by many abolitionists. A few of the more radical abolitionists promoted full social equality for blacks, including intermarriage, but most did not. During the antebellum period there is no record of even one marrying a black. William Lloyd Garrison called for the abolition of laws against intermarriage, but did not actually advocate it and appears to have believed it would become common only in the distant future. Archeologist Ephraim Squier (1821-1888) probably spoke for many when he wrote that he had “a precious poor opinion of niggers, or any of the darker races,” but he had “a still poorer opinion of slavery.” William Lloyd Garrison and Angelina and Sarah Grimke were unusual in favoring equal treatment for blacks in all respects.

A visceral repulsion for “amalgamation” has echoes to this day. Opposition to mixed marriage is the one “illiberal” view of race still publicly held by large numbers of whites. In 1991, at a time when huge majorities expressed approved views of racial integration and racial differences in IQ, 66 percent of whites were still prepared to tell a pollster they would disapprove if a close relative married a black.

Early Americans gave this disapproval the force of law. Between 1661 and 1725, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and all the southern colonies passed laws prohibiting interracial marriage and, in some cases, fornication. Of the fifty states, no fewer than forty had laws prohibiting interracial marriage at one time or another. It is well known that white slaveholders often had sexual relations with their female slaves — in the Caribbean this practice was called “nutmegging” — but this was thought vastly different from legal intermarriage or access by black men to white women. Many whites, especially in the North, found “nutmegging” itself sufficiently repulsive.

This was one reason why the charge, circulated by a disgruntled office seeker, that Thomas Jefferson had had children with his slave Sally Hemings was so potentially damaging. Jefferson had not only inveighed against intermarriage with blacks, but like many whites of the time, complained about their odor: “[They] secrete less by the kidnies [sic], and more by the glands of the skin, which gives them a strong and disagreeable odor.” Much of the satiric poetry that appeared in the press attacking Jefferson for his alleged amours in the slave quarters referred to this observation. “A Philosophic Love-Song, To Sally,” reads, in part:

When press’d by loads of state affairs

I seek to sport and dally,

The sweetest solace of my cares

Is in the lap of Sally. . .

She’s black you tell me — grant she be —

Must colour always tally?

Black is love’s proper hue for me

And white’s the hue for Sally. . .

What though she by the glands secretes; Must I stand shil-I shall-I?

Tuck’d up between a pair of sheets

There’s no perfume like Sally. . .You call her slave — and pray were slaves Made only for the galley?

Try for yourselves, ye witless knaves — Take each to bed your Sally. . .

Another poem excerpted here even describes Jefferson turning black in order:

Better to frolic with his Negro mistress: And straight, by transformation strange, From white to black his features change!

His tresses fall, and in their stead,

A fleece shoots curling from his head,

Flat sinks the bridge, that prop’d his nose,

Which round his nostril plumper grows:

His jaw protrudes, his lip expands,

Pah! He secrets by all the glands:

His legs inflect: his stature shrinks,

And from his skin all Congo stinks:

Behold him now, by Cupid sped,

In darkness sneak to Sally’s bed:

With philosophic nose inquire,

How rank the sable race perspire,

In foul pollution steep his life,

Insult the ashes of his wife:

All the paternal duties smother,

Give his white girls a yellow brother:

Mid loud hosannas of his knaves,

From his own loins raise a herd of slaves. . .

For many years thereafter, whites made much of the smell of blacks, which they considered a natural barrier to sexual relations. Satirical cartoons often referred to body odor, as did respectable newspapers. In a July 7, 1843, account of a mixed-race abolitionist meeting, the New York Times wrote, “There was a full and fragrant congregation. . .” An account of the same meeting in the Morning Courier and New-York Inquirer wrote that a hymn “was chaunted with great fervour as well as fragrancy by Mesdames of the ladies of colours.”

A satirical, anti-miscegenation novel published in 1835 by Jerome Holgate (1812-1893) called A Sojourn in the City of Amalgamation in the Year of Our Lord 19 — also made much of odor. It is set in the future in a time when whites think it their duty to marry blacks in order to combat race prejudice, but they still cannot abide their body odor. They carry machines that neutralize the smell; if the machines malfunction, whites vomit uncontrollably. Whites train themselves to endure the smell of blacks by sleeping with steaming platters of excrement next to their beds. The author was a Northerner, as were most of the book’s intended audience.

In 1837, shortly after this book appeared, a Pennsylvania constitutional convention voted to keep the vote in the hands only of white men. As we saw earlier, almost all states took similar measures, but the Pennsylvanians’ reasons are particularly interesting: “[T]o incorporate them [blacks] with ourselves in the exercise of the right of franchise, is a violation of the law of nature, and would lead to an amalgamation in the exercise thereof.” Giving blacks the right to vote was tantamount to miscegenation.

Anti-miscegenist feeling was so strong in the North that the easiest way to stir up opposition to abolitionists was to claim that what they really wanted was interracial sex and marriage. Many abolitionists repeatedly expressed strong disapproval of miscegenation, but to no avail. For opponents, the mere fact that speakers at abolitionist meetings addressed racially mixed audiences was sufficiently disgusting to make any charge believable. Only those abolitionists who firmly and publicly linked their proposals to colonization were safe from the charge of race mixing. There were 165 anti-abolition riots in the North during the 1820s alone, almost all of them prompted by the fear that abolition would lead to intermarriage.

The 1830s saw serious rioting as well. Beginning on July 4, 1834, New York City suffered eleven days of anti-abolitionist rioting, and levels of violence not to be seen again until the anti-draft riots of 1863. Independence Day had traditionally been celebrated with speeches and fund-raising by colonization societies, and there was considerable provocation in choosing it as the day for the American Anti-Slavery Society to read its Declaration of Sentiments to an audience that press accounts referred to as “obnoxiously mixed.” Rioters broke up the meeting and attacked stores and homes owned by known abolitionists. At first, not even the National Guard could control the mobs, and peace returned only after the American Anti-Slavery Society issued a “Disclaimer,” the first point of which was: “We entirely disclaim any desire to promote or encourage intermarriages between white and colored persons.”

Philadelphia suffered a serious riot in 1838. Abolitionists had had trouble renting space to hold their meetings, so in 1838 they built their own building. It was the biggest, most expensive structure in the city, and even before it was completed, one local paper called it the “Temple of Amalgamation,” and another “a stately edifice, sacred to the cause of amalgamation.”

Dedication ceremonies were to last three days and include leading abolitionists. On the evening of the second day, Angelina Grimke addressed the audience. People threw bricks through the windows and attacked several blacks as they left the building, but did not riot.

On the third day, May 17, several thousand angry Philadelphians — many of high social standing — gathered outside the hall. The mayor was summoned to the spot and is reported to have said: “We never call out the military here! We do not need such measures. Indeed, I would, fellow citizens, look upon you as my police! I look upon you as my police, and I trust you will abide by the laws and keep order. I now bid you farewell for the night.” After he left, the mob promptly burned the hall to the ground. Firemen arrived but only to make sure the fire did not spread to other buildings. After destroying the hall, the mob burned down the Friends Shelter for Colored Orphans and then attacked a black church.

A police commission that investigated the riot concluded:

It can be no surprise. . . that the mass of the community, without distinction of political or religious opinions, could ill brook the erection of an edifice in this city for the encouragement of practices believed by many to be subversive of the established orders of society, and even viewed by some as repugnant. . .

For many years, Americans used the term “amalgamation” to refer to the mixing of the races, but a new word appeared 1863. Two Democrats who opposed Lincoln’s reelection published a 72-page pamphlet called Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races, Applied to the American White Man and Negro. The authors, writing pseudonymously, were two New York City journalists pretending to be Republican supporters of the president. Lincoln had just issued the Emancipation Proclamation, and the two wanted to stir up opposition to Lincoln by driving home the idea that Republican and abolitionist policies would lead directly to race mixing — for which they proposed the term “miscegenation.” They argued that amalgamation was an inappropriate, metallurgical term, whereas a combination of the Latin (miscere [to mix], and genus [race]) “would express the idea with which we are dealing.”

The pamphlet had chapter titles like “The Blending of Diverse Bloods Essential to American Progress,” and it insisted that “[a]ll that is needed to make us the finest race on earth is to engraft upon our stock the negro element which providence has placed by our side on this continent.’ In a chapter called “Miscegenetic Ideal of Beauty in Women,” they wrote that ideals of beauty were arbitrary and that fair-minded whites should find blacks equally beautiful. In the final chapter they proclaimed boldly that a vote for Lincoln was a vote for miscegenation: “When the President proclaimed Emancipation he proclaimed also the mingling of the races. The one follows the other as surely as noonday follows sunrise.”

The pamphlet was wildly popular among Democrats, who trumpeted it as a revelation of what the dastardly Republicans really wanted. The new coinage caught on immediately, and Democrats were soon referring to Lincoln’s proclamation as the “Miscegenation Proclamation.” Abolitionists were taken in by the hoax too, and some of the wilder ones applauded it wholeheartedly. Angelina Grimke wrote the authors to say she and her sister Sarah were “wholly at one” with the arguments in the pamphlet. However, she raised a question of tactics: “[W]ill not the subject of amalgamation so detestable to many minds, if now so prominently advocated, have a tendency to retard the preparatory work of justice and equality which is so silently, but surely, opening the way for a full recognition of fraternity and miscegenation?” She was all for miscegenation but worried that talking about it openly would scare people.

It scared people for a long time. In 1967, when the Supreme Court finally ruled laws forbidding miscegenation unconstitutional in Loving v. Virginia, sixteen states still had such laws on their books. It is significant that even at that late date state legislatures were unwilling to tackle what was still a volatile issue. Nor would it be correct to assume that when states voluntarily abolished these laws, it meant legislators approved of mixed marriages.

For example, Massachusetts prohibited miscegenation from 1705 to 1843, but the ban was repealed for strictly libertarian reasons, not out of affection for blacks. The chief lobbyist for the change, John P. Bigelow, even wrote of intermarriage as “the gratification of a depraved taste.” Repeal was successful only because so many people were convinced the law was unnecessary and that natural disinclination would keep the races apart. The text abolishing the law clearly disapproves of miscegenation, saying only, “It is cruel, unjust and improper to. . . punish that as a high crime, which is at most evidence of vicious feeling, bad taste, and personal degradation.”

A number of southern states wrote anti-miscegenation laws into their constitutions. Although Loving v. Virginia invalidated these provisions, they remained on the books until removed by amendment. Voters in South Carolina and Alabama expunged the bans from their constitutions only in 1998 and 2000, respectively.

It is worth noting that substantial minorities in both states voted to keep the (now unenforceable) miscegenation bans: 38 percent in South Carolina and 41 percent in Alabama. Five of 47 South Carolina counties voted to keep the ban, as did no fewer than 23 of 67 counties in Alabama. In the 2002 vote in Oregon to strike out the passage in the constitution that kept blacks from even visiting the state, nearly 29 percent — more than one in four citizens — voted to keep the prohibition. These results suggest that although racial orthodoxy is unchallenged in all American institutions, it is far from universally accepted.

The racial views of previous generations of Americans were shared by other whites. The British Empire, for example, was a consciously racial undertaking. As Cecil Rhodes explained, “We are the first race in the world, and the more of the world we inhabit, the better it is for the human race.” Alfred Milner, a colonial administrator and later a viscount, explained: “My patriotism knows no geographical but only racial limits. I am an imperialist and not a Little Englander because I am a British race Patriot. It is not the soil of England. . . which is essential to arouse my patriotism, but the speech, the traditions, the spiritual heritage, the principles, the aspirations, of the British race. . .”

Rudyard Kipling, often called the poet of empire, wrote passionately about race in such poems as “A Song of the White Man,” “The Stranger,” “The White Man’s Burden,” and “Two Races.” It is in “Recessional” that he wrote of “lesser breeds without the law,” and the highest compliment he paid Gunga Din was to say “An’ for all ‘is dirty ‘ide/’E was white, clear white, inside.”

Kipling expected children to grow up with a proud sense of a racial identity that was never to be defiled. Here are the opening stanzas of “The Children’s Song”:

Land of our Birth, we pledge to thee

Our love and toil in the years to be;

When we are grown and take our place,

As men and women with our race.

Father in Heaven who lovest all,

Oh help Thy children when they call;

That they may build from age to age,

An undefiled heritage.

Even recent printings of A Child’s Garden of Verses include “Foreign Children,” in which Robert Louis Stevenson puts these words into the mouth of an English child:

Little Indian, Sioux or Crow,

Little frosty Eskimo

Little Turk or Japanee,

O! don’t you wish that you were me?

Similar sentiments can be found in other European languages, with the result that otherwise revered figures are revealed to have had very retrograde views on race. For example, the great French Protestant missionary to Africa, Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965), was the Mother Theresa of his time, a Nobel peace prize winner admired for his saintly qualities. Not long before his death, he wrote:

I have given my life to alleviate the sufferings of Africa. There is something that all White men who have lived here like I have must learn and know: that these individuals are a sub-race.

They have neither the mental or emotional abilities to equate or share equally with White men in any functions of our civilization. I have given my life to try to bring unto them the advantages which our civilization must offer, but I have become well aware that we must retain this status: White the superior, and they the inferior.

For whenever a White man seeks to live among them as their equals, they will destroy and devour him, and they will destroy all his work. And so for any existing relationship or any benefit to this people, let White men, from anywhere in the world, who would come to help Africa, remember that you must maintain this status: you the master and they the inferior, like children whom you would help or teach.

Never fraternize with them as equals. Never accept them as your social equals or they will devour you. They will destroy you.

Revising the Past

The point, of course, is that there is essentially no limit to the “racism” from the past that even a little digging will unearth. Up until the 1950s or 1960s, virtually anything anyone said or did about race reflected views that are unacceptable by today’s standards.

For today’s Americans it is an embarrassment to discover that their heroes were “bigots.” Historians usually ignore this or gloss over it. Most Americans have no idea Jefferson and Lincoln were “white supremacists,” perhaps because there have been deliberate attempts to conceal their views. For example, the Jefferson Memorial falsifies the third president’s views of blacks. Inscribed on the marble interior are the words: “Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people [the Negroes] shall be free.” When Jefferson wrote these words, he did not end them with a period, but with a semicolon, after which he wrote: “nor is it less certain that the two races, equally free, cannot live under the same government.”

A more honest but equally misguided approach to Jefferson is to bring out all the facts and then attempt to repudiate him completely. This is what author Conor Cruise O’Brien tried to do in a 1996 cover story for the Atlantic Monthly. After detailing Jefferson’s views, he concluded:

It follows that there can be no room for a cult of Thomas Jefferson in the civil religion of an effectively multiracial America — that is, an America in which nonwhite Americans have a significant and increasing say. Once the facts are known, Jefferson is of necessity abhorrent to people who would not be in America at all if he could have had his way.

In the conservative Washington Times, columnist Richard Grenier likened Jefferson to Nazi Gestapo chief Heinrich Himmler and called for the demolition of the Jefferson Memorial “stone by stone.”

It is all very well to wax indignant over Jefferson’s views 170 years after his death, but this only reflects ignorance of what other Americans thought. If we kick Jefferson out of the American pantheon, where do we stop? Clearly Lincoln must go, so his Memorial must come down too. Washington owned slaves, so his Monument is next. If we repudiate Jefferson, we do not just change the skyline of the nation’s capital, we repudiate practically our entire history.

American history, certainly up until the 1960s, is hopelessly tarnished with “racism.” Until 1964, after all, any private employer could refuse to hire any non-white, no matter how well qualified, and any business could refuse to do business with non-whites. Until 1965, the United States had an immigration policy explicitly designed to keep the country white. Until just a few decades ago, therefore, white Americans had a clear conception of their nation as white and an equally clear conception of their own group interests as whites. These concepts, taken for granted since colonial times, have been rooted out in what is, in historical terms, a blink of an eye.

Changes in language indicate how our thinking has changed. For example, the word “racism” did not even exist until the 1930s and was not used in its current sense until the 1960s. Before that time there was no need for the word, because “racism” was simply the way everyone thought about race. Just as there is no special word to describe the days on which the sun rises — because it rises every day — there was no word to describe people who believed what Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson believed. Because all people were “racist” by today’s standards, there was no need for a word to describe them.

When the word did appear in the 1930s, it was a description not of typical American thinking but of Nazi ideology. As late as 1971 the Oxford English Dictionary did not have an entry for the word. The United States established slavery, abolished it, established Jim Crow, and abolished that too without recourse to a word that today’s Americans seem to consider indispensable. When earlier Americans wrote about race, they wrote of antagonism, kindness, hostility, admiration, hatred, and a host of other feelings, but never about “racism.” The word does not appear even in so late and influential a book as Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma, published in 1944. Only in the context of mid-twentieth century assumptions did the word come into use as a pejorative description for what most people had always taken for granted.

Even the word’s precursor, “racial prejudice,” is a recent construction (and is the term used by Myrdal). Whatever James Monroe or Warren Harding thought about race, they would have been surprised to be told it was prejudice, that is to say, unreasonable preconceived judgment. “Racial prejudice” was an effective coinage because it implied that racial attitudes were a form of ignorance to be cured through education.

The very recentness of such terms as “racism” and “racial prejudice” is an indication of how quickly our thinking has changed. To make a serious moral failing out of concepts that did not even exist in the time of our grandparents is a sign of dizzyingly rapid change.

In terms of language, America’s experience has been like that of communist revolutions. In the Soviet Union, traditional assumptions were suddenly declared reactionary and criminal. Private enterprise and private gain, which had always been the driving forces of the economy, were outlawed, and new words had to be invented for what were now crimes. People who still believed in private gain had a “petty bourgeois mentality,” and those who wanted to keep the fruits of their labor were “stealing from the state.” Anyone who defended the free market was a “stooge of imperialism.” After the fall of communism, private gain was once more recognized as a normal and even necessary economic motivation, and the words that had been invented to criminalize it fell into disuse.

Traditional thinking about race has, of course, been criminalized. All manner of things whites used to say and do are now “racist,” and the grounds for the dreaded charge of “racism” always seem to be shifting in treacherous ways. However, it is possible to distill a few unifying principles that define the bounds of what whites must believe about race. The most important is that at least for whites, race is an insignificant matter. Race means nothing, explains nothing, and stands for nothing. Any generalizations about race are deeply offensive even if true, because all differences are irrelevant accidents of environment. The races are precisely, mathematically, geometrically equal in all but the most gross and meaningless outward characteristics. Races are, in effect, interchangeable. It should therefore make no difference if the neighborhood turns Mexican or the nation turns non-white or if white children marry Africans. This, then, is the central proposition about race as whites are to understand it — that race is not a valid criterion for any purpose. Any decision whites may make on the basis of race is immoral. There is, of course, one important exception: Whites may and sometimes must consider race as a category when working for the explicit benefit of people of other races.

This obliteration of group interests for whites is part of a complete reversal of how whites must now regard themselves. American colonists and Victorian Englishmen saw the steady expansion of their race as an inspiring triumph. Now it is cause for shame. “The white race is the cancer of human history,” writes Susan Sontag. Even “anti-racists” may be put off by the brutality of the metaphor, but they have absorbed enough similar ideas to know exactly what she means. An equally powerful sentiment is expressed by Noel Ignatiev of Harvard in a publication called Race Traitor. His slogan is “Treason to whiteness is loyalty to humanity,” and the lead article of the first issue of Race Traitor was called “Abolish the White Race — by Any Means Necessary.” By this he did not mean that whites should be physically eliminated, only that they should “dissolve the club” of white superiority whose purpose is to exploit non-whites. Christine Sleeter, writing for Mr. Ignatiev’s magazine, is specific about the defects of whites: “Whiteness, on the other hand, has come to mean ravenous materialism, competitive individualism, and a way of living characterized by putting acquisition of possessions above humanity.”

Whites now speak contemptuously about their own race as frequently as they used to take pride in it. The U.S. government sponsors a publication called Managing Diversity, which is supposed to help federal employees work better in an increasingly mixed-race workplace. One of its 1997 issues published a front-page story called “What Are the Values of White People?” The author, identified as Harris Sussman, Ph.D., first pointed out that most whites have been Christian and then wrote:

In the name of Christian values, they had the Inquisition. They called native peoples “savages” who did not qualify as human beings. They set up definitions of pagans, heathens, primitives, undeveloped people, which left Christians superior and dominant. They killed Jews and gypsies in the Holocaust.

In our post-modern vocabulary, “whites” or “the white man” is all we need to say to invoke this history and experience of injustice and cruelty. When we say “white people,” we mean the people of greed who value things over people, who value money over people.

Sweeping condemnations of this kind go unchallenged, even though many whites would find them excessive and distasteful. However, they differ only in degree from sentiments that are widely accepted. As James Traub of the New Yorker writes, when it comes to any discussion about race, whites must acknowledge that they are the offending party: “One’s hand is stayed by the knowledge of innumerable past hurts and misdeeds. The recognition of those wrongs, along with the acceptance of the sense of collective responsibility — guilt — that comes with recognition is a precondition to entering the discussion [about race].” Joe Klein, in New York Magazine, says any conversation about race must begin with a confession: “It’s our fault; we’re racists.” “Black anger and white surrender have become a staple of contemporary racial discourse,” writes another commentator. Needless to say, this is the view of race relations that blacks generally endorse. James Baldwin wrote that any real dialogue between the races requires a confession from whites that is nothing less than “a cry for help and healing.”

It is therefore almost conventional for columnist Maggie Gallagher to write that she thinks of herself as an American, a Catholic, and sometimes an Irish-American, but then to add, “I hate the idea of being white. . . I never think of myself as belonging to the ‘white race.’ Those who do, in my experience, are invariably second-raters seeking solace for their own failures. I can think of few things more degrading than being proud to be white.”

Presumably it is degrading for whites to feel pride in their race because there is nothing of which to be proud and much for which to be ashamed.

Every other race is thought to have good reason to speak of collective achievement, to have collective interests, and to have collective goals as a group. For whites all of this is washed away in an ocean of collective guilt for having oppressed non-whites. This, therefore, is the one way in which whites are allowed, even encouraged, to have a group consciousness. The meaning of whiteness — if it has any meaning at all — consists in affirming collective guilt and attempting to repudiate illegitimate privilege.

The most “anti-racist” whites speak of something called “white skin privilege,” or the undeserved advantages that come automatically with being white. Emily Hiestand, writing in the Atlantic Monthly, makes a common argument when she bemoans “the myriad built-in affirmative-action programs for white America, all those privileges so nearly invisible to many Americans.” Among “progressive” whites, it is common to work very hard to forgo those privileges, whatever they are, and to track down and eliminate every trace of personal racism, conscious or otherwise.

In his book, Long Way to Go, Jonathan Coleman writes about attending therapy sessions of a group called “Beyond Racism.” Whites sat in a circle and unpacked “an invisible weightless knapsack” that contains no fewer than forty-four “unearned assets” from which whites unconsciously benefit. Many of these alleged benefits are either trivial (whites “can choose blemish cover or bandages in ‘flesh’ color”) or simply the result of living in a country with a white majority (“I can turn on the television or open to the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely represented”). Similar exercises are common at the “diversity seminars” conducted in American corporations, in which whites are reminded of their sins and privileges. Whites suffer from a kind of racial original sin with which they are infected at birth. This is why they must approach the subject of race only as supplicants, seeking forgiveness.

For almost all whites, therefore, the only occasion on which they speak as whites is to apologize. There is only one kind of expression of white group consciousness our society permits: apology and self-abasement. Apology is one of the ways whites say “I’m not a racist.” President Bill Clinton was typical. In May 1997, he apologized for the Tuskeegee medical experiment that left black men untreated for syphilis. He has apologized to Africans for slavery. During a second-term visit to Africa, he apologized to Rwandans for failing to keep them from killing each other. In February 1998, he granted a posthumous pardon to Henry Flipper, who was the army’s first black commissioned officer but was given a dishonorable discharge. In December 1999, he pardoned Freddie Meeks, a black sailor who was convicted of mutiny in 1944. After a 1994 order from Congress to investigate the Meeks case, the Navy concluded that “the convictions were not tainted by racial prejudice” and refused to expunge them — but President Clinton pardoned Mr. Meeks anyway. Racial apology was a prominent theme in President Clinton’s otherwise sparing use of his pardon authority. Various church denominations have officially apologized for slavery.

One of our national holidays is essentially an apology. Martin Luther King, Jr. spent his life telling whites they were wrong and demanding that they change. Like most blacks, his goal was to advance the interests of blacks. Our country now celebrates only two individual birthdays: his and Jesus’. King is also to join Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Franklin D. Roosevelt as only the fifth American to be honored with an individual memorial on the Mall in Washington. Monsignor George Higgins writes that King’s life was “a sacrament, a sign of mediating grace,” and therefore it is appropriate to think of him as a saint. The United States government duly appropriates money every year to be spent in proper observance of King’s birthday. The great respect with which he is held reflects the widely proclaimed need among whites to apologize, and the more intensely they celebrate King, the more intensely they acknowledge their racial guilt.

The same sentiments prompted the decision to award the “Little Rock Nine” the Congressional Gold Medal. This is the highest honor the United States can bestow on a civilian and was first established by Congress to recognize the heroic achievements of George Washington. The “Little Rock Nine” are, of course, the nine black students who first integrated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957 after President Dwight Eisenhower called in federal troops to enforce an integration order. It was no doubt terrifying for them to brave the taunts of segregationists, but does their participation in a changing racial policy merit the highest possible national recognition? Senator Dale Bumpers of Arkansas has gone so far as to secure $150,000 from Congress to study whether Central High School should be designated a national historic site in the National Park System.

In 1995, the National Park Service urged that national historic landmarks be established for the “underground railroad,” the escape route by which some border state slaves escaped slavery. There is virtually nothing left of the “railroad,” which was mainly a network of guides and hiding places, and the country would be memorializing an idea more than any physical landmarks. The effect, once again, is to remind whites of the wrongs they have done and of the continuing need to apologize. Future generations are being to taught to continue the apology. According to Nathan Glazer of Harvard, more American seventeen-year-olds can correctly identify Harriet Tubman of the “railroad” than either Winston Churchill or Joseph Stalin.

To celebrate the civil rights movement, to celebrate the underground railroad, to reflect guiltily on slavery and Jim Crow — all these serve as constant reminders of the very things whites are told were most abominable about their nation’s history. No other country is so obsessed with condemning the actions of its own past, or celebrates its own evil with such enthusiasm.

Whites apologize to all non-whites, not just to blacks. In 1988 Congress voted to pay $20,000 to every Japanese who had been in a relocation camp during the Second World War. The $20,000, given to U.S. citizens and non-citizens alike, came with an official apology that is part of the larger apology about race.

American Indians get the same treatment. In 1991, what had been called the Custer National Battlefield Monument was renamed Little Bighorn National Battlefield Monument. The Indians who killed and mutilated Custer’s men now get equal billing with the U.S. Cavalry. This is part of the view that American history is a chronicle of brutality and barbarism rather than the spread of civilization.

In 1992, during the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of the New World, it was common to treat the event as the tragic first step in a chronicle of despoliation and rapine. To this end, both the state of South Dakota and the city of Berkeley, California, have replaced Columbus Day with a day to honor American Indians. Needless to say, the 400th anniversary of the discovery, one hundred years earlier, was marked with rather different sentiments. Today, the tone of apology is evident in a University of Oklahoma book, American Indian Holocaust and Survival. A similar book called American Holocaust: Columbus and the Conquest o f the New World argues that the pioneers were the moral equivalents of Nazi mass murderers.

American whites are not unique in their penchant for apology. A body of British clergymen called Churches Together in England, which is composed of the highest representatives of Catholics, the Church of England, and the Quaker and Orthodox churches, prepared guidelines more than two years in advance for bringing in the new millennium with appropriate apologies for past sins. The most prominent of these are sins of racism: the Crusades, slavery, and colonialism. A representative of the group explains, “We want to say we are sorry for the hurt that was caused long ago and is happening now.” On December 29, 1999, in the midst of the Christmas season, the group — which represents nearly every Christian in Britain — duly issued its apology for racism.112

In 1999, it was something of a fashion for whites to go to the Middle East and apologize for the Crusades — events that took place almost a thousand years ago. Nearly five hundred Christians from Europe, Australia, and the United States walked from Cologne, Germany, to Jerusalem, apologizing along the way. Once they arrived in Jerusalem they wandered the streets handing out apologies written in Hebrew and Arabic. On every trip to Africa, Pope John Paul II made a point of apologizing for the slave trade.

The Ultimate Solution

To recapitulate: For whites today, race is not a legitimate criterion either for personal decisions or public policy. Whites have no legitimate group interests or aspirations as whites. Whites are a flawed and guilty group. Racial diversity is a good thing.

It is not difficult to see that this leads to more than apologies. If whites are indeed guilty, racial preferences for non-whites in employment and college admissions are appropriate compensation. If race is not a legitimate criterion for white decisions, it means any preference they may have for other whites — whether as neighbors, business associates, fellow citizens, or spouses — is immoral. If diversity is a good thing, any majority-white neighborhood or institution is defective and must recruit nonwhites. Most fundamentally, it means whites have no possible grounds to object to non-white immigration, even if it will reduce them to a minority. Non-whites can rejoice in their increasing numbers because racial loyalty is legitimate for them, but whites must not resist dispossession because racial loyalty is wrong for them. Since racial diversity is good for whites, they should applaud any process that thins their numbers.

Again, President Clinton took the lead in publicizing demographic trends and in urging us to welcome them. After the Revolution and the Civil War, he described the reduction of whites to a minority as “the third great revolution of America.” He looked forward to the challenge of seeing “if we can prove that we literally can live without having a dominant European culture. Like many whites who claim to welcome minority status, his acts do not match his words. In 1999, before leaving the White House, he bought a home in Chappaqua, New York, in a zip code that was 93.69 percent white, 0.72 percent black, and 1.64 percent Hispanic. Mr. Clinton also had a chance to send his daughter Chelsea to racially mixed public schools in Washington, D.C. Instead, he sent her to the private Sidwell Friends School, which is probably no more integrated than Chappaqua.

Although very few whites like the idea of their children becoming racial minorities, they will not say so publicly. Former congressman Robert Dornan of California professes the required sentiments. In 1996, while he was still in the House of Representatives, an interviewer asked him about the changing demographics of his Orange County district. “I want to see America stay a nation of immigrants,” he said. “And if we lose our Northern European stock — your coloring and mine, blue eyes and fair hair — tough!” In his next election, he lost to a woman named Loretta Sanchez. This is exactly what Mr. Dornan’s cheerfulness about immigration should have prepared him for, but apparently it did not. He refused to concede defeat and charged Miss Sanchez’ supporters with vote fraud. He has not publicly changed his position on the advisability of whites becoming a minority.

If whites are to express any sentiment about it at all, they are supposed to be pleased at the thought of becoming a minority. A typical cover story of the travel section in the Washington Post had the following cheerful headline and sub-headline: “Forget the Alamo! Today’s San Antonio has little to do with that symbol of doomed Anglo imperialism. It’s a thriving capital of Hispanic culture, and a magnet for multicultural tourism.” Indeed, Mexican activists in San Antonio demand that the memorial to the defenders of the Alamo — David Crockett, Jim Bowie, William Travis — be torn down because it is an affront to Mexicans. According to the 1990 census, 51 percent of San Antonio’s 936,000 people were already of Mexican origin. If immigration from Mexico continues, a memorial to men who fought against Mexican domination will seem increasingly offensive and even absurd.

A largely white population is now an embarrassment and may even be considered an economic burden. Maine has been losing population for some time, and James Tierney, along-serving state’s attorney, believes ambitious young people go elsewhere because Maine is just too white. Of racial diversity he says, “This is not a burden. This is essential. This is an opportunity. In fact, maybe it’s more than just an opportunity.”

Other whites also promote diversity. Gwynne Dyer, a London-based Canadian journalist, takes for granted that “ethnic diversification” is a good thing for white countries, but notes that Canada and Australia, which have thrown open their borders to non-white immigration, have had to “do good by stealth.” Politicians understand the superior morality of diversity but think they must not let ordinary whites know what is happening: (Let the magic do its work, but don’t talk about it in front of the children. They’ll just get cross and spoil it all.) Being reduced to a minority will be good for whites, but the prospect must be kept secret from them for fear they will not see the wisdom of it. Dyer looks forward to the day when politicians can be more open about their goals.

Pauline Hanson is an Australian politician who opposes immigration policies that will reduce whites to a minority in her country. She has spoken of whites being “swamped” by Asians, who make up nearly half of current immigrants to that country. Such a view is naturally denounced as racist, and an Australian writing in the Washington Post described the people for whom Miss Hanson speaks as “the beast,” which is “alive and well, slimily squirming.” Needless to say, no one doubts that these reactionary forces will be crushed. The Chicago Tribune gave an article about Miss Hanson the sub-headline: “A new, anti-immigrant party appeals to some Australians who still harbor notions of remaining a Caucasian society [emphasis added].” Both in Australia and the United States, non-white immigration and the displacement of whites are thought to be both good and inevitable.

Becoming a minority, however, may be only the first step; with enough interracial marriage, whites might be made to disappear completely. It has become common to propose miscegenation as the final solution to the race problem. After all, if all races were melted into one, “racism” might disappear. “It would be a lot easier if each of us were related to someone of another color and if, eventually, we were all one color,” writes Morton Kondracke in the New Republic. “In America, this can happen.” “I think intermarriage may be the only way out [of our racial problems],” writes Jon Carroll of the San Francisco Examiner. Ben Wattenberg, noting the increase in interracial marriages, writes happily, “Does all this mean that as we move into the next century race will be much less of an issue? That we will all end up bland and blended? That (as I believe) we will fulfill our difficult destiny as the first universal nation?”

Even “conservatives” see intermarriage as the final solution. Douglas Besharov of the American Enterprise Institute says it may be “the best hope for the future of American race relations.” In a recent book, Stephen and Abigail Thernstrom wrote that the “crumbling of the taboo on sexual relations between the two races [black and white]” is “good news,” in that it will make it impossible to draw racial distinctions. Michael Barone, conservative pundit for U.S. News and World Report, agrees. “My great wish,” he says, “is that 50 years from now we will be so mixed there will be no more racial categories.”

John Miller is a reporter for National Review, which is thought to be the foremost “conservative” magazine in America. He thinks miscegenation is inevitable and will end group conflict. “Perhaps the best way to undermine the ideology of group rights is to permit this natural process of assimilation to work its way down the generations as people of mixed background marry and have children.” “In the future,” he adds confidently, “everyone will have a Korean grandmother.”

Andrew Sullivan, former editor of the New Republic, writes: “If the rate of inter-racial marriage increases, the next generation may well not identify as ‘black’ or ‘white’ at all. That’s a real fillip. Miscegenation has always been the ultimate solution to America’s racial divisions.” Mr. Sullivan is, of course, wrong. Miscegenation has always been the ultimate nightmare for whites. Unlike the people who coined the term, these authors are not satirically praising across-the-board miscegenation in order to stir up revulsion against it. They appear to be entirely in earnest. Here we find the final fruits of the racial revolution. What was always thought to be the worst imaginable outcome has now become the happy ending. Even as immigration reduces them to a minority, whites will dissolve into a glorious, universalist cafe au lait.

Of course, even if this were to be our future, it would not end racial conflict. Among blacks, differences in skin tone give rise to much friction. There is even conflict between Caribbean and native-American blacks who look no different from each other.

Needless to say, to have arrived at this final solution is to recognize the spectacular failure of the policies that have sprung from our revolution in racial thought. Civil rights laws were supposed to usher in a new Camelot of racial understanding and harmony, and liberal immigration laws were not supposed to change the demographic makeup of the country. Both assumptions were dead wrong: The percentage of whites is shrinking rapidly, and scarcely anyone pretends racial harmony is around the corner. But is anyone prepared to question the basic assumptions that underlie the racial revolution? Does anyone wonder whether we have miscalculated? Apparently not. Racial diversity has turned out to be a source of tension and conflict, and race is still a stubborn problem. The solution, therefore, is to toss the whole country into a blender and do away with race. We are to deal with the consequences of staggeringly misguided policies by embracing precisely what every preceding generation most feared and reviled.

Of course, no one points out that widespread miscegenation would not eliminate race; it would eliminate whites. Whites are no more than 15 percent of the world’s population and are having perhaps 7 percent of the world’s babies. No one is proposing the blender treatment for Africa or Asia. Not for a single non-white country is massive miscegenation proposed as a solution to ethnic tension.

And yet, given what whites are supposed to think about race — first, that it is a forbidden criterion for their purposes, and second, that whites are a shameful group anyway — what objection can they make to a “solution” that would do away with them as a distinct people? Whites may have a sentimental attachment to the notion of a white America, but if races are interchangeable this kind of sentimentality is selfish and irrational. Besides, if the only legitimate collective sentiment of whites is guilt, perhaps it is only right that whites fade away before the advance of the peoples they have wronged.

There has indeed been a revolution in racial thinking, but it has not brought the racial harmony for which so many hoped. Whites have come full circle. No longer do they talk about peopling the Americas from north to south. Instead, they now calmly consider disappearing as a distinct people if that is the price America must pay for the racial diversity with which our rulers have so unwisely saddled us.

Though long out of print, a limited number of copies of Race and the American Prospect are available for purchase from Noontide Press.