September 2009

| American Renaissance magazine | |

|---|---|

| Vol. 20, No. 9 | September 2009 |

| CONTENTS |

|---|

The Rise of Asian Race Consciousness

Anatomy of a Calamity

Elegy for the White Man

Obama and the Afro-Professor

O Tempora, O Mores!

Letters

| COVER STORY |

|---|

The Rise of Asian Race Consciousness

The one group that tried to assimilate is giving up.

Asian-Americans have long been known as the “model minority.” This is for two reasons. First, only a few Asian groups suffer from the social problems associated with blacks and Hispanics. Second, Asians have not made forceful demands on American society in the name of race. They have stayed away from identity politics and generally tried to assimilate.

The first of these reasons for being a “model” shows no sign of changing. With the exception of a few small groups such as the Hmong and certain Pacific Islanders, Asians continue to be hardworking, successful, and law-abiding. However, the past few decades have seen a marked increase in the willingness of Asians to band together across ethnic lines and to make demands in the name of race. Rather than trying to melt into the majority society as they did during the post-war period, Asians are beginning to adopt the tactics that other groups have shown to be successful. They are not nearly so focused on racial identity as blacks or Hispanics, but a group that showed every sign of downplaying the significance of race — of genuinely trying to assimilate — is now moving in the opposite direction.

No doubt this is partly explained by the increase in the number of Asians. When minority communities grow they exert a powerful attraction on their members that fosters parochial loyalties. At the same time, when other minorities turn their backs on assimilation and carve out alternative identities for themselves — and gain clear advantages from doing so — the temptation to do likewise is strong.

“Our parents told us don’t make a fuss, stay out of the public, eye,” explains Frank Wu, an Asian-American activist and law professor at Howard University, “but that advice serves no purpose in a diverse democracy.” It serves no purpose when every other group is making a fuss and pushing clearly ethnic interests.

The term “model minority” has been under attack for some time, but not from the people you might expect. It would be logical for blacks and Hispanics to object to the term, since it implies that they are less desirable minorities, but they are not the critics. It is the younger generation of Asians who now spurn a label that made their elders proud.

Who are the Asians?

Asians are still a small minority — at 13.4 million they are 4.4 percent of the population, according to the Census Bureau estimate of 2007 — but their impact is vastly disproportionate to their numbers. Forty-four percent of Asian-American adults have a college degree or higher, as opposed to only 24 percent of the general population. Asian men have median earnings 10 percent higher than non-Asian men, and that of Asian women is 15 percent higher than non-Asian women. Forty-five percent of Asians are employed in professional or management jobs as opposed to 34 percent for the country as a whole, and the figure is no less than 60 percent for Asian Indians.

The Information Technology Association of America estimates that in the high-tech workforce Asians are represented at three times their proportion of the population. Asians are also more likely than the American average to own homes rather than be renters. These successes are especially remarkable because no fewer than 69 percent of Asians are foreign-born, and immigrant groups have traditionally taken several generations to reach full potential.

It is a mistake, however, to paint all Asians with the same brush. Chinese (24 percent of the total) and Indians (16 percent) are extremely successful, as are Japanese and Koreans. Filipinos (18 percent) are somewhat less so, and the Hmong significantly less so. Hmong earn 30 percent less than the national average, and 60 percent drop out of high school. In the Seattle public schools, 80 percent of Japanese-American students passed Washington state’s standardized math test for 10th-graders — the highest pass rate for any ethnic group. The group with the lowest pass rate — 14 percent — was another “Asian Pacific Islanders” category: Samoans.

Different Asian nationalities can therefore have very distinctive profiles. For example, 40 percent of the manicurists in the United States are of Vietnamese origin and half the motel rooms in the country are owned by Asian Indians. On the whole, however, Asians have a well-deserved reputation for high achievement.

Asians are vastly overrepresented at the best American universities. Although less than 5 percent of the population, they account for the following percentages of the student bodies of these universities: Harvard: 17 percent, Yale: 13 percent, Princeton: 12 percent, Columbia: 14 percent, Stanford: 25 percent. In California, the state with the largest number of Asians, they made up 14 percent of the 2005 high-school graduating class but 42 percent of the freshmen on the campuses of the University of California system. At Berkeley, the most selective of all the campuses, the 2005 freshman class was an astonishing 48 percent Asian.

Asians are also the least likely of any racial or ethnic group to commit crimes. In every category, whether violent crime, white-collar crime, alcohol, or sex offenses, they are arrested at about one-quarter to one-third the rate of whites, who are the next-most law-abiding group. (The New Century Foundation report, The Color of Crime, found that Asians are many times more likely than whites to be members of youth gangs, so Asian crime rates may start climbing.) There is one exception: gambling. Chinese, in particular, are heavy gamblers but so are Vietnamese, Filipinos, Cambodians, and Koreans. Asians as a group are three to four times more likely than whites to be arrested for gambling offenses and a 1999 poll in San Francisco’s Chinatown found that 70 percent of respondents said gambling was the community’s number-one problem.

Asians are, in fact, such an important factor in the gambling business that after the MGM Grand Hotel & Casino opened in Las Vegas in 1993, it spent millions of dollars redesigning its entrance. It had been built to look like the mouth of a lion, the company’s logo, but many Asians would not enter the building because they thought it was bad luck to walk into the jaws of a beast.

Pan-Asian Identity

Asian immigrants started coming to the United States in the 1850s, and Asians have a rich history in North America. Like many other immigrant communities, they established self-help and other associations along national lines. These organizations fought discrimination but were mainly vehicles for mutual assistance, not the cultivation of a racial identity or the pursuit of political power. Recently, however, there is a clear tendency to establish broadly Asian organizations that are essentially expressions of racial solidarity.

Don Nakanishi, director of the UCLA Asian American Studies Center, explains that this is a burgeoning trend, especially in politics. What he calls a “pan-Asian” perspective is increasingly common, with Asians funneling money and votes to candidates who are of the same race but may be of a different national origin.

“A lot of it has to do with maximizing their political clout,” explains demographer William Frey. “They want to identify themselves as a pan-Asian group rather than segment themselves . . . It makes sense for Asians to band together.” It makes sense because there is strength in numbers and because race is a common bond.

OCA is the name of an influential Asian-American organization that grants scholarships only to Asian students and makes awards to outstanding Asian-American business executives. It was founded in 1973 as the Organization of Chinese Americans, but as part of its current pan-Asian emphasis, it is now known almost exclusively by its initials. When C.C. Yin, a San Francisco businessman, recently started an organization to nurture future political leaders, he did not limit it to Chinese, but called it the Asian Pacific Islander American Political Association.

Typical of the recent trend is a glossy magazine called AsianAm that was scheduled for launch in 2009. According to its mission statement, it was to be “the One Voice for all Asian cultures.” Likewise, when the Asian Real Estate Association of America opened a chapter in Las Vegas in 2008, its president, John Fukuda, noted that although Las Vegas has a section called Chinatown, “it’s really Asiatown.” Asians of all nationalities feel comfortable there.

There is no doubt that Asians are drawn to other Asians. Irvine, California, which used to be a typical white, conservative suburb, was 37 percent Asian in 2006, and has become a place where one need never speak English. Chinese are the most numerous Asian group, but Irvine also attracts Koreans, Japanese, and Vietnamese. Asians continue to increase in numbers and many schools have become heavily Asian. The University of California at Irvine (UCI) was 40 percent Asian in 2007 and sometimes jokingly referred to as the University of Chinese Immigrants.

Businesses have followed Asian communities, offering services in Asian languages and providing the comfort that comes from dealing with fellow ethnics. In 2006, two Chinese-oriented banks, Cathay General Bancorp and East West Bancorp were the second- and third-largest banks in Los Angeles County. Both started in Chinatown and moved out with their customers. Both were pursuing Asian customers in other states as well.

Asian identity seldom takes on the hostile, anti-white tone common with blacks and Hispanics, but it is not entirely absent. In 1997, Vietnamese-born Peter Nguyen was president of the UCLA Law School student bar association. To a suggestion that California had taken in too many immigrants, he replied, “Be warned: There is a lot of diversity here, and if you don’t like it, there are 49 other states and plenty of islands” to move to.

At about the same time, there were reports of Asians in high schools in Santa Clara County, California, who had joined gang-like groups called “Asian Pride.” They took collective revenge against slights from whites, did not socialize with whites, and harassed other Asians who did. They had an explicitly Asian identity, with a mix of members: Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, and Filipinos. This tendency does not, however, appear to be nearly so widespread or hard-edged as the racial identification of school-aged blacks and Hispanics.

In 2000, a Chinese-American named Carrie Chang started an angry magazine for Asians called Monolid. In language that seemed borrowed from black racial consciousness, the magazine urged all Asians to “rise up and grasp their identity” so as to fight “that ugly racism which is accosting us at every moment.” One of Miss Chang’s favorite themes was the need for Asian women to stop dating white men. About three-fourths of white-Asian marriages involve white men and Asian women, and according to C.N. Le, a Vietnamese-American who teaches sociology at the University of Massachusetts, “Some of the men view the women marrying whites as sellouts.”

Monolid took a more militant view. One article quoted Samuel Lin, a student at University of California at Berkeley, who deeply resented white men who dated Asians. “I think we should f — in’ kill them all,” he said. “Stick to your own flavor.” More significant than the aggressive tone of Monolid is the fact that it could not find a market. It lasted only a year or two.

Another representative difference between Asian and black identity can be found in Congress. There has been a Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus since 1994, but unlike the black caucus, it admits non-Asians whose districts include large numbers of Asian-Pacific constituents. White representatives from Hawaii and Guam have been members.

The non-white mainstream

Asians are nevertheless joining the non-white mainstream when it comes to making demands in the name of race. In 2000, for example, Asian actors were complaining that they were underrepresented in casting decisions and that they were too often typecast as martial arts experts or seductresses. Counting right down to tenths of a percent, they argued that since they were 3.8 percent of the population, they deserved more than 2.2 percent of the television and movie roles. “We are depriving children of knowledge of the world we live in by not providing them with an accurate portrayal of the American scene,” said Chinese-American actor Jack Ong. Asian Week complained that in Hollywood movies “the heroic Caucasian protagonist saves the helpless people of color.”

Asians have also begun to act more like blacks and Hispanics on college campuses. In 2000, 100 Asian students demonstrated on the campus of the University of Illinois at Chicago, demanding establishment of an Asian-American studies program, an Asian cultural center, and a special academic support network for Asians. They were also furious because the university had put out a press release bragging it had received an award for supporting diversity — but had failed to mention Asians. “We will not tolerate being treated that way,” said Haley Nalik, president of the Coalition for Asian American Studies.

In California, which has by far the largest number of Asian university students, activists were frustrated by the assumption that Asians were doing well and did not need special assistance. They pointed out that Bangladeshis and Malaysians, as well as islanders from Guam and Tonga were underrepresented on campuses, and demanded that administrators stop pretending Asians as a group were successful. In what is becoming an increasingly typical pan-Asian approach, the overrepresented Asians, such as Chinese and Koreans, insisted that the smaller ethnicities be counted separately and be more aggressively recruited if they were underrepresented. In 2007, the University of California system agreed to start counting no fewer than 23 Asian and Pacific Islander categories to ensure than no one gets short shrift.

Increasingly, like “non-model” minorities, Asians keep a sharp eye out for perceived slights, as the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) discovered in 2008. Interviews, endorsements, socializing with sponsors, and professional-amateur rounds are important sources of revenue for the LPGA Tour, and organizers announced that players would not be allowed to compete if they did not speak English well enough to take part. Asian organizations immediately went on the offensive, and Asian-American state legislators in California threatened to pass a law that would ban such a policy in California. The LPGA quickly backed down. I’m pleased they have come to their senses,” said California assemblyman Ted Lieu.

In 2008, CNN commentator Jack Cafferty complained that China made “junk with lead paint” and exported “poisoned pet food,” and called Chinese leaders “basically the same bunch of goons and thugs they’ve been for the last 50 years.” This prompted throngs of Chinese to gather outside CNN offices in Hollywood to demand that he be fired. They sang the Chinese national anthem and waved Chinese and Taiwanese flags, in a demonstration that drew both mainland and Nationalist Chinese.

Joseph Groh, the owner of a popular Philadelphia restaurant, was proud of keeping things the way they were since the diner was founded in 1959 — the same soda fountain, ceiling fans, sparse menu, and wooden booths. Asians, however, were offended because he kept the restaurant’s original name — Chink’s — the nickname of the man who started it. For years, Asians pressured Mr. Groh to change the name, but he refused. In 2008, Asians succeeded in persuading a city agency to deny a lease for a second location. “We actually stopped it [the restaurant] from expanding,” said Tsiwen Law, general counsel of the Greater Philadelphia OCA. “Going outside of his neighborhood will be difficult, because we will respond,” he added.

In 2009, OCA also slammed the singer Miley Cyrus for what it claimed was gross insensitivity to Asians. A snapshot of the then-16-year-old taken with a group of friends showed her and several others pulling their eyes into a slanted position that is supposed to look Asian. A Los Angeles Asian-American, Lucie Kim, went even further, filing a civil rights claim for $4 billion in compensation for all Asian-Americans.

Actions of this kind, which have been staples of black and Hispanic activism, would have been unthinkable to Asian leaders of a generation ago.

Like the larger minorities, Asians are also beginning to push racial-ethnic interests in politics. Gautam Dutta is executive director of the Asian-American Action Fund. “Historically, they [Asians] are less focused on politics,” he says, “but they are an emerging bloc, suddenly in the last few years in both state and national elections.”

The California state legislature has had an Asian Pacific Islander Legislative Caucus since 2001, and it joined the black and Hispanic caucuses in threatening to cut off funding for the state judicial system if Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger did not appoint more non-white judges. Caucus member Ted Lieu argued that it was manifestly unfair that although Asian-Americans made up 12.6 percent of the state’s population, they represented only 4.6 percent of the governor’s 260 judicial appointments. (He was unconcerned by the fact that the state bar, from which all appointments must come, was 85 percent white.) He also introduced legislation that would require the state to keep track of 21 different Asian ethnicities to make sure less successful groups were getting the attention they need. “To the extent that I can help out on issues statewide affecting Asian Pacific Americans, I’m going to try and do that,” he explained.

Some more-recently-arrived Asian groups are not yet at the pan-Asian level of organization and make narrowly ethnic political appeals. In 2007, two independent Vietnamese candidates set off what was called a “political earthquake” by beating both the Republican and Democratic candidates — one white, the other Hispanic — for a place on the powerful Orange County, California, Board of Supervisors. As the Los Angeles Times explained, the Vietnamese upset the favorites by clever use of absentee ballots and by “shrewdly courting ethnic loyalties.” Vietnamese were pleased. “All candidates should know by now they can’t win an election around here without the support of the Vietnamese community,” said Lan Nguyen, president of the Garden Grove Unified School District Board of Trustees.

That same year, the Orange County town of Westminster became the first in the nation to have a city council that was majority Vietnamese. They were not a majority of voters — under 40 percent — but they voted overwhelmingly for fellow ethnics while non-Vietnamese split their votes among a number of candidates. The county’s white and Hispanic politicians began translating campaign literature into Vietnamese and posing for photos with the yellow and red flag of the former country of South Vietnam — a gesture that appeals to those who fled the Communists. “I don’t believe in central Orange County you can be a successful elected official without the Vietnamese vote,” said state senator Louis Correa of Santa Ana, who hired Vietnamese-American staffers and even took part in a hunger strike to protest human rights abuses in Vietnam.

Some Asian office-holders, however, are discovering the limits of single-ethnicity politics. In San Jose, California, Madison Nguyen became the standard bearer for the Vietnamese community when she was elected in 2006 to the city council on the strength of a massive ethnic vote. Three years later she was fighting for her political life after Vietnamese voters — 30 percent of the electorate — turned on her because she would not stick to a narrowly Vietnamese agenda. “I can’t say yes all the time,” she said. “I’m not just a daughter in the Vietnamese-American community alone.” Vietnamese voters felt betrayed. Her opponents put a recall petition on the ballot, but in March 2009, Miss Nguyen kept her seat with 55 percent of the vote.

Asian Indians are organizing politically as well. Approximately one-third of the population of the New York City suburb of Edison is Indian, and politicians take notice. Sikhs have won election to low-level offices in New York City, and the Sikh Coalition managed to get a bill pending in the city council to allow city employees to wear turbans. The American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin is now the biggest doctors’ group in the nation after the American Medical Association.

At the pan-Asian level, the most successful political force is probably the 80-20 initiative, established in 1998 with the aim of delivering a massive Asian vote — 80 percent of it — to candidates who agree to its demands. Its founders include S.R. Woo, former lieutenant governor of Delaware, and Chang-lin Tien, former chancellor of UC Berkeley, hardly people who failed to get a foothold in the mainstream.

National politicians take 80-20 seriously. During the 2004 presidential elections, nine of the 11 candidates, including John Kerry, John Edwards, Howard Dean, Joseph Lieberman, and Dennis Kucinich, signed an 80-20 statement saying that if elected they would order the Labor Department to hold public hearings on discrimination against Asians, and would meet with Asian leaders to discuss progress in combating such discrimination.

For the 2008 election, Chris Dodd, Joe Biden, and Mike Gravel agreed to the 2004 pledge but went further, promising to appoint enough Asian-American judges to triple their number on the bench and to consider appointing an Asian to the Supreme Court. John Edwards, Bill Richardson, and Hillary Clinton signed a statement agreeing to keep appointing Asians “until the current dismal situation is significantly remedied.” “What is the secret that 80-20 can get such perfect answers from presidential candidates?” asked the 80-20 website. “Its ability to deliver a bloc vote!” More and more politicians are finding that Asians are yet another pressure group whose demands must not be ignored.

Asians have many interests they want their representatives to push — celebration of Asian holidays, open immigration policies, foreign-policy considerations — but one of the most consistent is that Asians be included in minority set-asides for government contracting. The fact that most Asian groups are economically more successful than non-Asians does not reduce their enthusiasm for these programs.

Nguyen Ai Quoc is the pen name of a history instructor at a southern California community college. This article will continue in the next issue.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

Anatomy of a Calamity

Cincinnati and the wages of cowardice.

Peter Bronson, Behind the Lines: The Untold Story of the Cincinnati Riots, Chilidog Press, 2006, 152 pp., $14.95 (softcover).

The Cincinnati riots of 2001 were the worst racial violence the United States has seen since the Los Angeles riots of 1992. For three days, blacks burned, looted, and wrecked some 120 business, at an estimated cost of $14 million. The police made 600 arrests but, astonishingly, there were no deaths.

Peter Bronson, a veteran journalist with the Cincinnati Enquirer, has written what is probably the only book-length account of riots. He pulls no punches. This is a frank account of how Cincinnati capitulated to blacks, betrayed its police, and paid for its cowardice for years afterwards. Needless to say, this book has been largely ignored.

One of Cincinnati’s worst neighborhoods is known as Over-the-Rhine. In 1850, it was a bustling German immigrant community of 43,000 people. In 1990 it was 71 percent black and, like so many ghettos, its population had plummeted to about 10,000. By 2001 it was a hive of crime, drugs, welfare, and hatred of the police.

Mr. Bronson points out that Cincinnati’s white power structure had unwittingly stoked feelings of grievance and lawlessness. During the five years leading up to 2001, Mr. Bronson’s own paper, the Enquirer, had published at least a dozen major stories criticizing the police as potentially racist and violent.

Democratic politicians had pushed Cincinnati even further: They had let protesters crowd into city council meetings, where they shouted about “oppression” and “white devils.” The rowdies were black, so council members feared accusations of “racism” if they asked police to maintain order. These disruptions — the significance of which became clear later — were broadcast to astonished citizens over public-access television.

The conventional view, which Mr. Bronson considers simple-minded, is that the riots were touched off by a police shooting. It is certainly true that at 2:20 a.m. on Saturday morning, April 7, 2001, white officer Stephen Roach shot and killed 19-year-old Timothy Thomas in the worst part of Over-the-Rhine. Thomas had more than a dozen outstanding warrants — though none was for a violent crime — and was running from the police. He and Officer Roach came racing around a corner towards each other almost simultaneously, and the policeman fired. When, moments later, other officers ran up, the first words out of a pale and shaken Mr. Roach were, “It just went off.” Mr. Bronson thinks the man probably panicked. Shortly afterwards, however, Mr. Roach claimed Thomas reached down to hike up his trousers and he thought Thomas was going for a gun. Maybe Thomas did reach for his pants. In any case, he was unarmed.

Word of the shooting spread quickly, but as Mr. Bronson notes, there was no rioting on Saturday or Sunday, and none until late Monday. He argues that it was what happened in the interval that lit the fuse.

One key actor in the crucial early moments was the number-two man in the police department, Assistant Chief Ron Twitty. He was an affirmative-action black who had vaulted over the heads of white officers to the highest position ever held by a black in the department. It was an open secret that his work was poor and that others had to cover for him. He had banged up his police cruiser several times and tried to hide the fact (he was finally forced out of the department in 2002 for yet another wreck). He was more of a community liaison — and not a very good one — than a police commander.

The chief of the department, Tom Streicher, was out of town that weekend, so the assistant chief was in charge. When Chief Streicher returned on Monday after the Saturday shooting, he was astonished to learn that his deputy had not called a press conference to discuss the incident and deny rumors. Temperatures were rising, black radio was broadcasting accusations of cold-blooded murder, but the department had done nothing. Assistant Chief Twitty would stumble even more seriously later on.

Mr. Bronson notes that what did happen on Monday probably contributed as much as anything to the rioting. That morning there was a meeting of the city council’s Law and Public Safety Committee at city hall. The committee chairman, a young white liberal named John Cranley, realized that any meeting about police business would attract an even angrier crowd than usual, but specifically ordered that no officers be present for fear they might upset blacks.

A huge mob packed the room, spilling out of the spectators’ area and surrounding the committee members. One man in yellow-and-black African robes carried a huge sign that said, “Stop Killing Us or Else.” He brandished it so close to committee members they flinched and dodged to keep from being hit. The crowd set up such a din that Chairman Cranley could hardly be heard through his microphone. He tried to recess the meeting, but the crowd ignored him. He got up to leave but was jostled and intimidated, and returned to his seat. “I can’t deal with this,” he said, thinking his mike was off.

Instead of calling officers to clear the room, Chairman Crowley turned the mike over to the protesters! Most of the time, there was so much yelling that harangues about “all the brothers who have been shot and choked to death by the police” were inaudible.

Every American city has its equivalent of Al Sharpton, and Cincinnati’s was Rev. Damon Lynch III, leader of the Black United Front. Nearly three hours into a hopelessly chaotic meeting, Mr. Cranley offered Rev. Lynch the mike. What the preacher said was clearly audible and broadcast to the city on public-access television: “Nobody leaves these chambers until we get the answer. Members of the Black United Front are standing at the doors, because nobody leaves until we get an answer.” The Law and Public Safety Committee was hostage to a minister. The crowd whooped with delight, as shouts of “long, hot summer,” and “we’re gonna tear this city up” filled the air.

But the crowd had been howling for hours and was tired of just talking about action. It wanted the real thing. It soon had enough of Rev. Lynch and began pouring out of the hearing room. On the way out, blacks started breaking windows. Some came back to city hall later and broke some more, for an official count of 200 smashed windows.

Police Chief Tom Streicher believes this pitiful performance showed blacks they could ignore authority. “The antics in council, widely broadcast . . . fueled the riots more than anything,” he says. Mr. Bronson calls the council meeting one of “the great institutional failures” that led to chaos.

Chaos was not long in coming. The mob left city hall and made its way to police headquarters, picking up hundreds of bored, out-of-school black children. Soon there was a crowd of about 1,000 people in front of police headquarters, facing a line of two dozen men in blue. Blacks began throwing rocks and bottles and smashed a window in the police building. Officers were about to wade in and arrest the perp but were shocked to get the order to stand down. Police Chief Streicher was away at an emergency meeting and Assistant Chief Twitty was in charge. He ordered the police to do nothing, while the mob desecrated the monument to fallen officers just across the street from police headquarters. Blacks tore down the flag from the monument, spat and stomped on it, and ran it back up upside down. Rocks, bottles, and curses continued to rain down on the officers.

Then Assistant Chief Twitty actually did something. He went outside the building and called for a bullhorn. He put in new batteries to make sure it was working — and then turned it over to the rioters. Mr. Bronson writes that Cincinnati police are furious about this to this day. They were expecting him to try to disperse the mob; instead he gave a symbol of police authority to men who used it to call for violence. By the time Chief Streicher got to headquarters all the windows were smashed, the doors were broken, and a black was still shouting into the bullhorn with Assistant Chief Twitty by his side. The chief pushed out the rabble with mounted police and cleaned up stragglers with tear gas.

Many studies have concluded that an early show of overwhelming force usually stops riots. A SWAT team officer who was at headquarters that day is convinced the Twitty approach was the worst possible way to handle the demonstrators. “There were no consequences for their actions, and they could see that,” he told Mr. Bronson. “It just made it worse.” Twice that day, blacks had made a mockery of authority; it was a prelude to the real violence that followed.

Property and whites

For the next two days, the mob had two targets: property and whites. Egged on by black radio and even white media that spoke of “insurrection” and “uprising” rather than “mob violence,” blacks surged through downtown, looting and burning. Police fired beanbag rounds from shotguns and secured one block only to see looters move on to another. The police were dodging live fire, and one officer miraculously escaped injury when a bullet bounced off his belt buckle, but police did not fire a single lethal round in return.

Rioters attacked whites by blocking intersections to immobilize cars. They would then smash a windshield, drag out the terrified whites, and beat them. Police probably saved dozens of lives by speeding to the scene, clearing out rioters with beanbag rounds, collecting the victims, and getting out before the crowd could regroup and overwhelm the police.

Mr. Bronson writes that the media were virtually silent about the racial angle, which made things worse. Many victims were whites from out of the area who had driven in to “see what a riot is like.” Honest reporting would have kept them away. Instead, newspapers ran big photos of blacks showing bruises from beanbag rounds, and gave the impression the police were causing the violence by firing at random.

The cruelest insult came from the city. After the first day of riots, when officers staggered home after 16-hour shifts, they learned that Mayor Charles Luken had gone on CNN to say: “There’s a great deal of frustration within the community, which is understandable. We’ve had way too many deaths in our community at the hands of the Cincinnati police.” Even the mayor was saying police were responsible for the riots. Mr. Luken later acknowledged he had behaved stupidly: “I wish to hell I had never said that,” he admitted to Mr. Bronson.

The national media picked up the idea that Cincinnati police had a brutal record of killing blacks, and the myth of “15 black men” who had “died in police custody” swirled from coast to coast. Time magazine called Cincinnati “a model of racial unfairness.” As the police belatedly pointed out, hardly any of the 15 who died were “in police custody.” They were trying to kill policemen, and were shot by officers who feared for their lives. The national media did not care. America was witnessing an “uprising” over discrimination, poverty, and joblessness.

On Thursday, after two days of severe rioting, the mayor finally did what police had been recommending and ordered a curfew. Violence dropped sharply and Friday was peaceful. The next day, however, brought another nasty incident. Exactly one week after the shooting, there was a mass funeral for Timothy Thomas at Rev. Damon Lynch’s church in Over-the-Rhein. Kweisi Mfume, then head of the NAACP was there, along with one of Martin Luther King’s children and — to the shock and disgust of the police — Ohio governor Robert Taft and his wife, Hope. “He never once came to a police funeral,” says SWAT officer John Rose. “And here he was, going to this.”

Needless to say, all Governor Taft and his wife got was a humiliating earful about white wickedness from Rev. Lynch, but his presence in the middle of what had been a riot zone was a security nightmare. Despite their contempt for his gesture of solidarity with a black criminal, police had to be sure his limo was not stopped and attacked.

As the funeral broke up and people poured into the streets, a band of out-of-town blacks unfurled a banner, blocking an intersection. Six officers responded as they had during the riots, clearing the intersection with beanbag rounds to make sure the governor could get through if he had to come that way. Several of the demonstrators claimed they were injured by “excessive force” — the police believe the ringleader was cut by a bottle thrown by demonstrators — and the city handed over $235,000 in damages. The mayor himself called for a federal investigation of “the Beanbag Six,” which found — years later — that they had done nothing wrong.

Mr. Bronson notes that the city acted just as cravenly after the riots as before. Whites were yearning for “root causes” to put right and for “programs” that would make blacks happy and grateful, so Cincinnati went down a well-worn path: “appoint a commission, blame white society, then ignore the findings and argue about them, while waiting for someone who is honest and brave enough to point out that riots are caused by rioters.”

In the process, the city agreed to outside monitors and inspectors who would supervise the police and reform the city. It spent $10 million on “so-called solutions, lawsuits, court hearings and reports.” Mr. Bronson heaps scorn on the overpaid mooncalves who were supposed to teach old pros like Chief Streicher how to run the police department. It was like “trying to reform the Marine Corps with experts from the Salvation Army.” The politicians never turned the spotlight on themselves, or on the disastrous committee meeting at which blacks made a mockery of authority and broke out windows at city hall. The cowards blamed the people who showed real courage: the police.

Officers reacted as they usually do when they risk their lives for a city that turns on them. Many veterans left the force. Those who stayed stopped taking risks. Why collar and frisk a probable black criminal when there was a good chance Rev. Damon Lynch would screech about “racial profiling” and the city would side with the criminal? Police spent less time in Over-the Rhine, and just three months after the riots, arrests were down 30 percent; shootings were up 600 percent. Murders soared to new records. It was several years before Chief Streicher could get the men to put their hearts back into police work.

Another consequence of the riots could have dealt the city a blow from which it might not have recovered. Rev. Lynch, unsatisfied with the pandering, urged all black and black-sympathetic organizations to boycott Cincinnati. “Police are killing, raping, planting false evidence,” he explained, “and are destroying the general sense of self-respect for black citizens.” For months, the media handed him the biggest megaphone in the city, giving him more air and press time than the mayor. A host of performers, including Bill Cosby, Whoopi Goldberg, Wynton Marsalis, and Smoky Robinson canceled appearances. The city is thought to have lost at least $10 million from conventions and conferences that stayed away.

Loss of revenue came at a bad time. With downtown already jumpy because of riot scares and the police slowdown, some of Cincinnati’s landmark businesses closed. For a time, the city seemed to be headed towards the permanent desolation of Detroit and Akron. If the black population had been larger the city might have died, but Mr. Bronson says it has pulled out of its nosedive. He writes that the election, in 2006, of a city council that appreciates the police was a big step back from the brink.

It was of course the police, during three days of pitched battles, who saved the city, but all they got was blame. “Never, ever was there said a single word of gratitude to us for anything,” Chief Striecher explained afterwards. “Quite honestly, we never expected it. We knew we would be chastised and publicly humiliated by city council.”

What lessons does Mr. Bronson draw from the riots? One is the terrible damage done by his own profession. Time and again, the press blamed police and excused rioters, and never seemed to realize it was fanning the flames. “The media are playing a largely overlooked role as agitator and inciter,” he writes. Like the whites in city government, they could not set aside “the belief that all black grievances are legitimate and must be assuaged at all costs.”

The unspoken message of this book is that authority figures must show backbone. They should never have let blacks turn city council meetings into shouting matches. They should never have appointed an incompetent assistant police chief just to placate blacks. They should have clamped down at the first sign of lawlessness rather than fret about provoking a reaction. The Cincinnati riots were just one chapter in the much larger story of the decades-long demoralization of the entire country.

This sobering book is not without redemption, however. Officer Stephen Roach went on trial in September 2001 for negligent homicide and, to the astonishment of Chief Striecher, was acquitted. (It was a bench trial; he probably could not have gotten a fair jury in Cincinnati.) He went on to take a police job in the neighboring town of Evandale, where he became an honored and even much-commended member of the force.

America is supposed to be the land of second chances. Will Cincinnati — and the nation — get a second chance?

| ARTICLE |

|---|

Elegy for the White Man

Clint Eastwood ponders white displacement.

Gran Torino, screenplay by Nick Schenk, produced and directed by and starring Clint Eastwood, Warner Brothers Pictures DVD, 2008, 116 minutes, Rated R.

Clint Eastwood has starred in many memorable films since the 1960s as the strong, silent, violent hero. He has also directed several movies, two of which, Unforgiven and Million Dollar Baby, won Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Director. He remains best known, however, for his role as “Dirty Harry” Callahan, the fearless, .44 magnum-wielding San Francisco police inspector. Gran Torino was rumored to be the final Dirty Harry film, with the Callahan character in retirement. It isn’t, but there are similarities between Dirty Harry and the hard-bitten character he plays here.

At its best, this movie convincingly portrays the dispossession of white, middle-class America, but it is ultimately dishonest: At the end we are to believe that although immigrants are alien to begin with, they will soon become good Americans — perhaps even better Americans than whites.

Mr. Eastwood plays Walt Kowalski, an aging, embittered blue-collar worker who spent most of his life working on an assembly line at a Ford plant. He is also a decorated combat veteran of the Korean War, and remains tormented by his wartime experiences. He lives in a close-in Detroit suburb, the only white man left in what was once a white, working-class neighborhood. His new neighbors are an extended family of Hmong refugees from Southeast Asia.

Mr. Eastwood is a skilled filmmaker, and he conveys Walt’s sense of isolation effectively. The Hmong are poor and strange. The parents do not speak English and do not maintain their houses. Walt’s house is by far the best kept in the neighborhood, and the only one that flies an American flag. He is clearly the alien here, a point reinforced by the matriarch of the next-door Hmong family, who wonders outloud why he is still hanging around after all the other Americans have moved away.

We learn all we need to know about Walt Kowalski and his own family in the first few minutes. The film opens with the funeral of his wife. He is stiff and uncomfortable, and shakes his head in disgust as his grandchildren file in, inappropriately dressed and disrespectful. His two adult sons and their families are vapid, materialistic yuppies, interested in Walt only if they can get something from him. Toward the end of the film, Walt clumsily tries to reach out to his eldest son, but is — predictably — rebuffed.

Walt’s racial views reinforce the stereotype of an elderly white, working-class man. Walt is a racist simply because, well, he is a white, working-class man, and that’s how Hollywood sees them all. He makes derogatory remarks about everyone, and has many colorful slurs for his Asian neighbors (gooks, slopes, zipperheads, Chinks, swamp rats, egg rolls), his Italian barber and friend (Doo-wop, Dago, Guinea), his Irish contractor friend (drunken Irishman and Mick) and of course, blacks (just spooks — apparently “nigger” is too naughty, even for Walt).

This is supposed to show Walt as a product of his times, a man stuck in racist 1950s America, but only in Hollywood do white working-class men speak that way. Walt Kowalski is an updated version of Archie Bunker, who was also an angry, racist white veteran (of the Second World War).

But just as Walt has trouble with his children, so do the Vang Lors, the family next door. The mother is a recent widow, and she worries that her son, Thao, will be caught up in a Hmong gang. Thao’s attempts to escape from its clutches are the main story line of Gran Torino.

As part of his initiation into the gang, Thao is supposed to steal Walt’s prized possession, the 1972 Gran Torino Sport Coupe that gives the film its name. Thao bungles the theft and wakes up Walt, who grabs his M1 Garand rifle but bungles the collar, and Thao gets away.

A few days later, the gang comes by the Vang Lors’ house to give Thao a second chance. His family refuses to let him go with them, and there is a fight. When it spills onto Walt’s yard, he storms out of his house with his M1 and orders the gangbangers off his property. Caught unarmed, they slink sullenly away.

His Hmong neighbors now see Walt as a hero and begin leaving food on his doorstep, much to his consternation. Walt just wants to be left in peace so he can spend his final days drinking beer on his porch, but the Hmong now feel indebted to him. Sue, the feisty and sassy Hmong teenage daughter, and her mother bring Thao over to make him apologize, telling Walt that the boy dishonored the family by trying to steal his car and must work off the debt.

Walt wants nothing to do with Thao, but in true Hollywood style, Thao is a hard worker who wins Walt’s grudging respect and affection. The transformation of Thao into an inter-racial surrogate son will come as no surprise to people who remember the plot of the 1970s television sitcom Chico and the Man, which starred Freddy Prinze and Jack Albertson in roles similar to those of Thao and Walt.

Walt’s relations with his own family continue to be rocky, but he draws closer to the Vang Lors. He rescues Sue from blacks who want to rape her, and is invited to Hmong family celebrations. He drinks foreign beer, learns to like Hmong food, and chats with a Hmong teen-aged girl who treats him respectfully, unlike his own granddaughter. His surrogate fatherhood deepens as he sets about “manning up” Thao. He gets him a job, lends him tools, and imparts to him the wisdom he would have liked to pass on to his sons and grandsons, if only he had had a relationship with them.

But the gang has not forgotten about Thao, and the violence ratchets up. Walt tries to protect his neighbors, but he is not Dirty Harry. His violence doesn’t solve problems; it makes things worse. The gang shoots up the Vang Lors’ house, kidnaps Sue, and beats and rapes her. Thao expects Walt, the tough, rifle-wielding ex-soldier, to deliver vengeance, and the stage is set for the final, predictable confrontation. Walt is heroic, but not in the predictable way.

There are two themes running through Gran Torino. The first is the corrosive effect of violence. Clint Eastwood has portrayed many violent men over the years, and in the Sergio Leone films, his character used violence casually, self-servingly, and not really in the name of justice, but effectively. Violence is how tough men on a lawless frontier survive. In the Dirty Harry films, violence serves justice. Harry Callahan confidently dispatches criminals who clearly deserve to die.

In Gran Torino, violence begets nothing but more violence. There is a message here that is missing from Mr. Eastwood’s earlier films: violence corrupts.

Walt is tormented by Korea. He won the Silver Star for wiping out a Chinese machine-gun nest, but he killed unarmed Chinese soldiers who were trying to surrender. At one point in the film, Sue calls Walt a good man, but he thinks of himself as a murderer. Walt sees the violence he unleashed with the gang spiral out of control, but he finally ends it through sacrifice, not violence. Gran Torino can almost be seen as an atonement for all the killing in Mr. Eastwood’s earlier films, and he must have been disappointed that it was snubbed at the Academy Awards.

Or perhaps Mr. Eastwood no longer has Harry Callahan’s moral confidence because Dirty Harry’s world no longer exists. The far more interesting theme of Gran Torino is white displacement. Walt Kowalski is part of Harry Callahan’s America — white America — but that America is gone.

The rules no longer apply. Walt Ko-walski played by those rules. He fought America’s wars, built its cars, kept his nose clean, raised a family, bought a house, maintained it, and for what? To give it away to aliens? His reward for trying to preserve order in his neighborhood is — at first — to be despised by the newcomers.

His trim house and his tidy lawn are an affront to the Vang Lors and the other Hmong. He shames them, because they cannot do what he can. He can fix his house, maintain his lawn, and impose order — with a rifle, if necessary. They can do none of these things, and are at the mercy of forces they cannot control: weeds, dry rot, peeling paint, gangs. Walt is the white man who builds things, keeps order. They are Third-Worlders, who get pushed around.

But Walt, too, now faces a force he cannot control: demography. His house will pass from the white world to the non-white world. No white family will live in it after he’s gone. It is only a matter of time. The Hmong granny realizes this, which is why she calls him a stubborn white man and a dumb rooster. He’s trying to fight something he can’t control.

Walt loves his neighborhood, though, which is why he didn’t leave in the first place. He teaches Thao how to fix things and shows the Hmong they can take care of their houses. He tries, single-handedly, to get rid of the gang. Since he can’t make his neighborhood more white, he tries to make his neighbors more white, and that is what the film is really about: white America graciously giving way to its non-white future. This is clear at the beginning, as Walt buries his wife while the Vang Lors welcome a new baby into their home.

We shouldn’t be bothered by this, the film tells us, because the people replacing us will be just as good, if we only help them a little — a sort of cultural affirmative action. They may even be better. They would never play a video game at their grandmother’s funeral, as Walt’s grandson does. They value tradition and family more than we do. They would never try to push old folks off into a retirement home the way Walt’s son does. Their religion is not cold and formal, like the Catholic ceremony that opened the film, but warm, and people-centered.

This is the movie version of the standard Republican line on immigration: We should let the non-whites in because they are younger and more vibrant and have better family values. Walt’s — and the movie’s — true revelation is that he likes the Hmong family more than he likes his own children.

What is worst about this film is a vague undercurrent of dishonesty. The way Mr. Eastwood presents his characters and their post-industrial Detroit leaves the impression that he knows the score, that he knows what is replacing white America will not be better, but cannot say so. He would lose his post-Harry Callahan respectability. Instead we are left with stereotypes and clichés recycled from old television programs. Walt Kowalski isn’t Dirty Harry; he is Archie Bunker with an M1 Garand and a death wish. Even the ending is a cliché: Walt’s feckless granddaughter, who covets the Gran Torino, doesn’t get it. Thao rides off into the sunset in Walt’s one abiding love.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

Obama and the Afro-Professor

What the Gates affair says about US race relations.

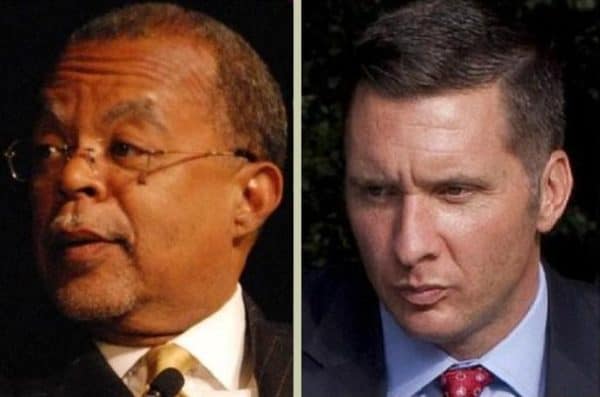

When I read the first report on the arrest of Henry Louis Gates, Jr., it was obvious that this storm in a teacup would be blown up into a racial hurricane. Not surprisingly, President Obama was not tardy in meddling in what was supposedly a local, Cambridge affair. The fact that Mr. Obama has since effected something of a volte face and even had a beer with the much-maligned Sgt. Jim Crowley and his histrionic victim does not detract from the incident as having demonstrated the precarious state of US race relations.

Crowley and Gates (Image Credit: Wikimedia)

If Prof. Gates is worried about racial justice he should consider the plight of a white man in South Africa, a game farmer by the name of Ettienne van Wyk. Mr. van Wyk was arrested by black policemen for transporting his animals without a permit. He and his farm manager, Zacharia Duvenhage, were tossed into a cell with 14 hardened black criminals: murderers, robbers, rapists. At around 3.00 a.m. Mr. Van Wyk was sodomized by some of the inmates, while the others sang songs to drown out his screams. The station commander was sound asleep during this impromptu a cappella performance.

Mr. Van Wyk later sued the South African minister of police for R1.2 million or $150,000 in damages. Mr. Duvenhage, who was not sodomized, sued for only R350,000 or $44,000 for suffering several minor injuries.

Why is this incident, so many thousands of miles away, relevant? Because the case of Mr. Van Wyk represents something like the mirror image of Henry Louis Gates’s minor spat with the law. He, “a black man in America,” was arrested and taken to the police station by a white policeman conscious of his duty to enforce the law. He suffered no injury, except to his zeppelin of an ego. Yet the global media lavished more attention on Prof. Gates, a self-confessed creation of affirmative action, than on the war in Afghanistan and a few other wars combined.

As for Ettienne van Wyk, a white man arrested for the minor offence of transporting his own animals and sexually assaulted by black criminals while under the authority of a black policeman, the liberal champions of racial justice will never spare a thought for him, let alone a minute of prime time,

Prof. Gates knew that he could rely on the universal belief that all blacks are victims. Perhaps that is what prompted his fit of rage in the first place. He was playing the agent provocateur, hoping to increase his standing as a victim, which is hard to do when you have a cushy Harvard job and a house in a high-toned neighborhood.

Of course, even when a black is in the wrong, to liberals he remains a victim. Something, or someone, “made him do it.” If Prof. Gates overreacted, it was only because of whites and white racism. The historical burden of racial pain is too much to bear, and no amount of material comfort will ever suffice to attenuate its effects, which may flare up at any moment.

In a normal world, of course, an alleged slight to the dignity of some affirmative-action academic would not be news. There would be no global theater for blacks to play out their sense of inadequacy in front of a sympathetic audience of guilty whites.

However, the so-called fight against racism is like the class struggle of Marxist lore. Affirmative action and diversity are to Harvard what dialectical materialism was to the Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University in the old Soviet Union. Recent jokes about the USSA — the United Socialist States of America — having taken over where the USSR left off may contain a grain of truth.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. lives in a world in which whites and blacks alike are indoctrinated in the official ideology. In the Ivy League, black is king. Academics live in the same mortal fear of being accused of “racism” (or “sexism”) as Catholics did in the days of the Spanish Inquisition, when an accusation of heresy could bring death at the stake. The professor is no doubt surprised that anyone, including Mr. Obama, should have listened to the white policeman’s version at all. In his rarefied world, no white would ever speak up to a black, let alone arrest one.

Sgt. James Crowley did the US and the world a favor. He pricked the bubble of Prof. Gates’s privileged existence. For once, diversity parasites all over America got the terrifying message that they might be treated equally with whites. If only for that, the man deserves some sort of police medal.

But incidents of this kind and the controversy they stir up have the even greater value of demonstrating that diversity is a burden and not a benefit. They shatter the usual polite silence on race that prevents rational discussion of the dilemma facing not only America, but the entire world.

Dr. Roodt is a prominent Afrikaner novelist and commentator.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

Postscript on the Gates Arrest

There is very little to add to what others have said and written about the arrest of “Skip” Gates. Most important, however, is that it is very hard to doubt Sgt. Crowley’s version of what happened. He is, according to all accounts, a by-the-book officer, and he wrote his arrest record before he became an unwitting media star. There is no reason to think he cooked it. Another officer who was with Sgt. Crowley at the time of the arrest also signed the report, which adds to its credibility. (It is curious, however, that although the Boston Globe had an Internet link to the arrest report when the paper first wrote about the Gates arrest, the link soon disappeared. The Globe must have decided the report was not to the professor’s credit.)

At the same time, a certain Sgt. Leon Lashley of the Cambridge police was present at the arrest, and says Sgt. Crowley was right to take Prof. Gates in for disorderly conduct. Sgt. Lashley, who is black, has been widely derided as an “Uncle Tom” for siding with his white colleague. It would have been much easier for him to join the anti-whites and call Sgt. Crowley a racist so, again, we can assume that Sgt. Crowley’s version of events is true.

What, therefore, are we to conclude? As Dr. Roodt notes above, in a sane world, Prof. Gates would have got derision rather than sympathy. We can be certain that if a white celebrity had behaved arrogantly towards a policeman, insulted the officer’s mother, and caused a disturbance — and then got a free ride downtown — everyone would think he got exactly what he deserved. People love to see the high and mighty brought low through their own vanity.

Even if the arrest itself had been unjustified, it should be clear to anyone that Prof. Gates’s yelping about “racial profiling” is as transparent a case of the pot criticizing the kettle as we are ever likely to see. It was he who immediately saw race in the encounter, not Sgt. Crowley. Virtually the first words out of his mouth were about being “a black man in America,” and he repeatedly called Sgt. Crowley a “racist.” Barack Obama, who is reported to be a pal of Prof. Gates, also saw no further than race. He admitted he did not know the facts but still said the Cambridge police behaved “stupidly.” All he needed to know was that the officer was white and the man in cuffs was black.

In the short run, this incident has been a huge benefit to Henry Louis Gates. He has been an overrated academic for years, but hardly a household name. For a few days in July, though, he was the most talked-about man in America, and within his pampered circle he was no doubt petted and feted. In the real America, however, few whites were fooled. After the president’s “stupidly” remark, his ratings among whites dropped 7 percent. (Among blacks and Hispanics, the same remark netted him a 9 point gain in ratings. Blacks and whites continue to live in different worlds.)

But let me make a prediction about Prof. Gates: He will not make his promised documentary on “racial profiling.” Despite the liberal bias in the media, the facts in this case are too clear and too easy to dig up. Prof. Gates would do well to let this story die as quickly as possible. The longer he holds it before the public, the longer he lets us examine it, the clearer it becomes: Prof. Gates behaved like an ass. Maybe he even behaved stupidly.

| IN THE NEWS |

|---|

O Tempora, O Mores!

Discovering the Truth

In the May issue of American Renaissance, we reviewed The 10,000 Year Explosion by Gregory Cochran and Henry Harpending. It is a remarkable account of why evolution has speeded up over the last 10,000 years, and why different human populations are therefore diverging more rapidly than ever.

Remarkably, the cover story of the March issue of Discovery magazine took up the same subject. It quoted Professor Harpending as saying, “It is likely that human races are evolving away from each other. We are getting less alike, not merging into a single, mixed humanity.” The article did not shirk from the implications this research has for racial differences in intelligence. Of course, it quoted hand-wringers, such as Francis Collins of the National Institutes of Health: “When it comes to brain functioning, let’s be honest: That is a tinderbox of possible explosive reactions based on a very unpretty history . . .”

On the whole, however, the article gave the impression people like him are afraid of the truth. It quoted Steven Pinker of Harvard making a concession that sounds like wishful thinking: “People, including me, would rather believe that significant human biological evolution stopped between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago, before the races diverged, which would ensure that racial and ethnic groups are biologically equivalent.” Gregory Cochran is quoted as mocking “the extraordinary claim . . . that evolution somehow stopped once we developed culture. You’re allowed to change, but only below the neck.”

The article notes that geneticist Robert Moyzis of UC Irvine puts a “sunny spin” on recent findings: “It would be boring if all the races were fundamentally the same. It’s exciting to think that they bring different strengths and talents to the table.” Of course, to mention differences of any kind is to ask just what those differences are and what they mean for society. [Kathleen McAuliffe, Are We Still Evolving? Discover, March 2009, pp. 51-58.]

Remarkably, only one or two subsequent letters to the editor expressed shock at this matter-of-fact reporting on evidence for racial differences in intelligence. More and more people seem to be waking up to the evidence of their senses.

It’s Official

After the presidential election last year, Prime Minister Baldwin Spencer of the tiny Caribbean twin-island nation of Antigua and Barbuda said he would rename Antigua’s highest mountain, 1,319-foot Boggy Peak, after Barack Obama. On Tuesday, August 4, Mr. Obama’s birthday, it became official. Mr. Spencer presided over the re-christening ceremony at the base of the mountain, unveiling a stone sculpture and plaque honoring the president. “This great political achievement by Barack Obama resonated with me in a way that I felt compelled to do something symbolic and inspiring,” he told a crowd of about 300 people. “As an emancipated people linked to our common ancestral heritage and a history of dehumanizing enslavement, we need to at all times celebrate our heroes and leaders who through their actions inspire us to do great and noble things.”

The plaque reads, “Mount Obama, named in honor of the historical election on Nov. 4, 2008, of Barack Hussein Obama, the first black president of the United States of America, as a symbol of excellence, triumph, hope and dignity for all people.” In the audience were the charge d’affaires for the US Embassy for the eastern Caribbean, a black American congresswoman who was born in Jamaica, and actress Angela Bassett, who wept during a performance of a calypso song inspired by Mr. Obama called “For You Barack.” “It wasn’t only about Barack Obama,” she said. “It was about the history of black people around the world and the struggle and sacrifices that have been done so that he could rise to the position that he is in today.”

Although Mr. Obama remains wildly popular on the islands, not everybody was excited by the name change. Lester Bird, leader of the opposition Antigua Labor Party, called the change “silly” and said the country might as well “name it for Michael Jackson.” [Anika Kentish, Antigua’s Highest Peak Renamed ‘Mount Obama,’ AP, Aug. 4, 2009.]

Sabor Latino

Hispanics spend about $30 billion a year on groceries in the US, and Food Lion, a grocery chain based in Salisbury, North Carolina, which operates about 1,300 stores in the Southeastern and mid-Atlantic states, wants that money. Last August, Food Lion began gearing five stores in the Raleigh-Durham area to Hispanics: more dry goods, such as beans, tortillas and spices, and meat and produce Hispanics like. Food Lion also gave employees lessons in Spanish and Hispanic culture, and ran advertisements boasting about “Sabor Latino,” or “Latin Flavor.”

The company says the program went so well that it has converted 10 more stores in Raleigh-Durham to the Hispanic-friendly format, along with 13 other stores in central North Carolina. By summer’s end, it plans to make over 19 stores in Charlotte. Its goal is to turn 59 of its 503 North Carolina outlets into temples of Sabor Latino.

Bill Greer, spokesman for the Food Marketing Institute, says Food Lion is just one of several American grocery chains hopping to the salsa beat. “Food is a very important part of the Hispanic culture,” he explains. “We’ve had several mainstream chains develop whole formats around Hispanic food.” [Sue Stock, Food Lion Caters to Latinos, News & Observer (Raleigh), July 11, 2009.]

How It Happened

After last November’s election, most commentators claimed Barack Obama’s victory was made possible by a multi-racial coalition of blacks, Hispanics, and other non-whites, along with liberal whites and young people. The Republicans, they said, could no longer rely on their white base alone to win national elections because there are fewer white voters. Critics of this view countered that Sen. McCain lost precisely because he did not appeal to whites, and that many whites who could have supported the Republicans stayed home.

Recent data from the US Census Bureau bears out this analysis. For all the talk of a “historic” election, the percentage of eligible voters who cast ballots in November declined for the first time since 1996 to 63.6 percent. In 2004, the figure was 63.8 percent. The big drop — down 1.5 percent to just under 72 percent — was in whites, of age 45 and over, who usually vote Republican. This had an impact in key battleground states, such as Ohio and Pennsylvania. This also brought the overall white voting rate down to 66 percent from 67 percent in 2004.

Black turnout increased by 5 percent to 65 percent, nearly matching the white rate. Hispanics improved turnout by 3 percent, and Asians by 3.5 percent, to bring each group to nearly 50 percent. In all, non-whites made up nearly 1 in 4 voters in 2008, the most ever. When asked why they didn’t go to the polls, 46 percent of non-voting whites said they didn’t like the candidates, weren’t interested, or had better things to do — up from 41 percent in 2004. [Hope Yen, Voting Rates Dip in 2008 as Older Whites Stay Home, AP, July 20, 2009.]

A significant number of whites were indifferent to a choice between a black liberal and white who did not even hint at positions that favored whites.

Freedom Comes to Texas

Jose Merced, 46, is a native Puerto Rican who now lives in Euless, Texas, a suburb of Fort Worth. He is also a Santero, or Santeria priest. As part of his religious duties he slaughters animals; sometimes as many as nine lambs or goats, sometimes as many as 20 chickens or other birds. His Euless neighbors called the police, who enforced a long-standing city ordinance banning animal sacrifice.

Mr. Merced tried to get a permit to slaughter animals in his house, but the city refused. He then sued the city for violating his religious freedom. Mr. Merced lost his first round in federal court, but on July 31, the Fifth US Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans ruled that the Euless ordinance placed a “substantial burden” on Mr. Merced’s “free exercise of religion,” and that he has the right to kill animals in his backyard.

“Now Santeros can practice their religion at home without being afraid of being fined, arrested or taken to court,” says a happy Mr. Merced. His lawyer agrees: “It’s a great day for religious freedom in Texas.” Euless city attorney William McKamie says he plans to file a motion for a rehearing. The Catholic charity, the Beckett Fund for Religious Liberty, helped pay Mr. Merced’s legal fees, and he got help from Douglas Laycock, who is a law professor at the University of Michigan. [Linda Stewart Ball, Court Gives Santeria Priest OK to Sacrifice Goats, AP, July 31, 2009.]

Panthergate Update

As we reported in the July issue, the Justice Department raised eyebrows in May when it suddenly dropped charges against three members of the New Black Panther Party who were accused of voter intimidation. Minister King Samir Shabazz and his pals had appeared in battle gear at a Philadelphia polling station last November, waving billy clubs. The men failed to appear in court to answer charges, and the judge was set to issue a default judgment against them, when Justice did an about face. When department officials could not come up with a good explanation for the reversal, speculation centered on the role Obama political appointees played in the decision.

It appears to have been a significant role. Justice Department lawyers were apparently in the final stages of seeking sanctions against the Panthers when acting Assistant Attorney General Loretta King of the department’s Civil Rights Division ordered a delay. She then met with Associate Attorney General Thomas J. Perrelli, the department’s number-three political appointee, who approved the decision to drop charges. Only anonymous sources within the department have been willing to talk about this.

The US Commission on Civil Rights now wants the full story, saying the department has so far offered only “weak justifications.” On June 16, the commission sent a letter to the Justice Department stating that the turnaround caused the commission “great confusion” because the Panthers were “caught on video blocking access to the polls, and physically threatening and verbally harassing voters.” Commission Chairman Gerald A. Reynolds pointed out that other groups would not have been treated so leniently. “If you swap out the New Black Panther Party in this case for neo-Nazi groups or the Ku Klux Klan, you likely would have had a different outcome,” he says.

When asked to comment on the commission’s letter and the chairman’s remarks, a Justice spokesman said only that the department is “committed to vigorous enforcement of the laws protecting anyone exercising his or her right to vote.” [Jerry Seper, Panel Blasts Panther Case Dismissal, Washington Times, Aug. 4, 2009.]

No ‘Hate’ Here

Barbara Frische is a white woman who has lived in her East Austin, Texas, neighborhood for 10 years. Miss Frische is a minority in East Austin, which has been full of blacks and Hispanics since the late 1920s. Recently, however, more whites have moved in, buying and renovating houses. Property taxes are beginning to price out the older residents. On July 24, Miss Frische awoke to the sound of glass shattering in her four-year-old son’s bedroom. She called police, who discovered that someone had thrown a brick through the window. Attached to the brick was a note reading, “Keep Eastside Black. Keep Eastside Strong.”

Austin police say whoever threw the brick faces criminal mischief and deadly conduct charges, but without “hate” enhancements. According to police spokesman Sgt. Richard Stresing, the note didn’t include “hate speech.” The president of the Austin chapter of the NAACP thinks the police have it right. “Throwing a brick into somebody’s home, that’s a crime,” says Nelson Linder. “It’s a criminal act, and that’s how it should be addressed.” [Juana Summers, Police: Brick Thrown Through Window Not Hate Crime, Austin American-Statesman, July 25, 2009.]

What would they think of a brick that went through the window of a black or Hispanic family with a note reading, “Keep Austin White. Keep Austin Strong”?

| LETTERS FROM READERS |

|---|

Sir — It was with great sympathy that I read Christopher Jackson’s piece, “A White Teacher Speaks Out,” in the July issue.

Thirty years ago I taught in a London school, whose enrollment included many pupils who had recently migrated to the UK from the West Indies. I can corroborate Mr. Jackson’s experiences and his conclusions. Most whites do not know what blacks are like in large numbers and their first encounter is, indeed, a shock. Blacks certainly are violent and the whites caught up in it are very much to be pitied. Just as Mr. Jackson did, I attended parent-teacher conferences at which children begged their parents to take them out of school while the parents insisted there was nothing to fear.

Your readers might be interested in an article I wrote for the late John Tyndall’s magazine Spearhead (No. 85, July 1975), entitled “Anarchy at Tulse Hill.” Of his first few days as a teacher, your author writes, “Suddenly I was in darkest Africa; except I wasn’t in Africa, I was in America.” So it was for me and all the other whites, pupils and teachers — native Britons, of course — at the Tulse Hill School in London. We, too, were in darkest Africa, except we were in England. And like your author, I found, and find it still, incomprehensible that white parents and white society can permit such conditions to exist.

The school was closed and demolished in 1990.

Richard Edmonds, Sutton, England

Sir — John Ingram’s suggestion in the August issue that we should replace “race realism” with “white advocacy” confuses science with policy. Race realism is not an esoteric body of knowledge meant only for the advocates of white interests.

William Shockley, a pioneer in modern race realism (see Roger Pearson’s Shockley on Eugenics and Race), understood its nuances. After he concluded that genetic inheritance has a major impact on racial differences in intelligence, he speculated that the black-white gap could be bridged by preferential education. Genes are predominant, but environment also counts. Therefore, if blacks got markedly superior educations while whites were shortchanged, their levels of intelligence might converge. This is a black-advocacy position Al Sharpton could support, but it is one based on race realism.

A different consequence of race realism for blacks might be that some would become less demanding. One can always hope.

Let’s keep “race realism,” with its connotation of objectivity. What whites and blacks do with race realism’s conclusions is another matter.

Chris Woltermann, Fort Recovery, Ohio

Sir — Attorney John Ingram does a great job reviewing the terminology used to describe white folks who take justifiable pride in being white and ask only to be named fairly and accurately. Mr. Ingram suggests “white advocate” as a benign alternative to the left’s insulting terms. Sorry, counselor, but at least to me, the suggestion carries unintentional overtones of white supremacy and, by extension, bigotry. Also, doesn’t “white advocate” sound just a little bookish and stiff-necked?

Taking my cue from Mr. Ingram’s point that nearly all white Americans “from George Washington to Dwight Eisenhower” never had to label their traditional views on race, I’m happy to stick my (white) neck out and suggest we call ourselves simply “traditionalists.”

O. M. Ostlund, Jr., Altoona, Pa.

Sir — I just can’t see the problem you fret over in your August issue. Surely, the blacks have given us an acceptable model. Collectively they are blacks; individually each is a black. (Imaginary) problem solved, no?

Anthony Young, London, England

Sir — Readers of American Renaissance who are interested in self-protection, but are unable or unwilling to carry a concealed firearm may want to look into defensive canes from Cane Masters (www.canemasters.com). They make top-quality canes and walking sticks out of hickory and oak. I have a hickory cane with a “triple grip,” and I can assure you that I would prefer it over mace or any tactical folding knife.

The great thing about defensive canes is that you can legally carry them practically anywhere, even in airports and government offices. Try that with a baseball bat! Also, unlike a knife, a cane is always in your hand, ready for use. There are several places online where you can buy cane-fighting videos. When choosing a cane or stick, however, be sure to choose hickory (my recommendation) or oak. Walnut and cherry are not combat grade.

Name Withheld, Va.

You must enable Javascript in your browser.