Hispanic Consciousness

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, April 2007

Traditionally, when Americans thought of race, they thought of the often painful history of relations between blacks and whites. This view is out of date; the United States now has several racial fault lines rather than just one. The scarcely-noticed handful of Hispanics present in the 1950s has become the largest racial minority in the country.

Like blacks, many Hispanics have identities — racial, ethnic, or national — that prevent full or even primary identification as Americans. Immigrants from Mexico, who account for two thirds of all Hispanics, are especially ambivalent and often even hostile towards the United States. It is part of their national culture to see the United States as an imperialist power that humiliated and dismembered Mexico after the Mexican-American War of 1846 to 1848. Many openly preach reconquista or reconquest — at least culturally, and perhaps even politically — of those regions of the American Southwest that were once Mexican.

There are already parts of the United States in which people live in exclusively Spanish-speaking environments, where they have no need to be part of the larger culture. If Hispanic immigration, both legal and illegal, continues at its current pace, these areas will grow, and become increasingly isolated and alien. At the same time, through sheer force of numbers, Hispanics are imposing their language, politics, and cultural preferences on other Americans.

Blacks have been part of the United States for hundreds of years. Brought involuntarily, they have a historic and moral claim on America. Hispanics, whose presence in large numbers is recent and unplanned, do not have the same claims, but this has not prevented them from making similar demands. They have been quick to assume the mantle of victimhood, to attribute poverty or social failure to racism, and to take advantage of preference programs originally established for descendants of slaves. Even Hispanics who have just arrived in this country do not hesitate to accept advantages in the name of “diversity” or “equal opportunity” that are denied to whites.

Hispanics are therefore very much like blacks in their vivid sense of their own group interests, their tendency to see the world in starkly racial/ethnic terms, and their reluctance to adopt the broader American identity whites think necessary for integration and assimilation. This racial/ethnic identity is kept fresh by the continuous arrival of new immigrants. However, even if immigration were to stop tomorrow, there are now enough Hispanics — especially Mexicans — to maintain a particularist, parochial identity indefinitely. In the space of just a few decades our country has established a second group of Americans with many of the most disturbing characteristics of blacks: racially distinct, with an inward-looking identity, suffering disproportionately from poverty, crime, illegitimacy and school failure.

Who are the Hispanics?

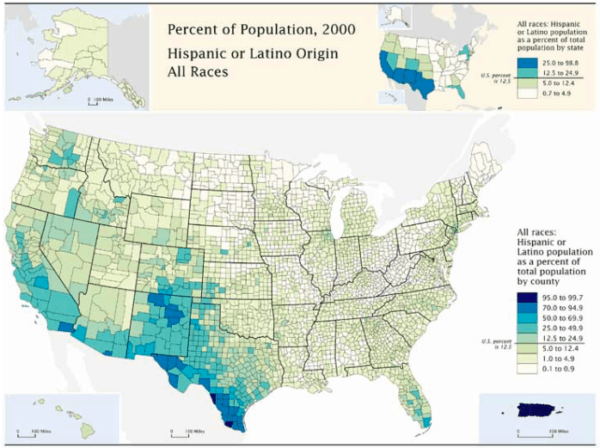

In 2005, there were 42.7 million Hispanics in the United States. They made up 14.4 percent of a population that was 66.9 percent white, 12.3 percent black, 4.2 percent Asian, 1.4 percent Pacific Islander, and 0.8 percent American Indian.

A large majority of Hispanics — 66 percent — are of Mexican origin. No less than 20 percent of the population of Mexico now lives in the United States, and one out of every seven Mexican workers has migrated here. Many more would like to come: According to a recent survey, almost half of all Mexicans said that they would move to the United States if they had the chance.

The 33 percent of Hispanics who are not from Mexico have mainly the following origins: 17 percent Latin American, nine percent Puerto Rican, and four percent Cuban. The characteristics of these populations are often quite different, with Cuban immigrants generally more economically successful than those from Mexico, Central America, or Puerto Rico.

Between 2000 and 2005, the Hispanic population increased at an annual rate of 3.7 percent, no less than 14 times the growth rate for whites, and more than three times the black rate. This increase was due both to high birthrates and to immigration of about 800,000 Hispanics every year. Much of this immigration was illegal. The best estimates are that Hispanics account for 78 percent — and Mexicans for 56 percent — of the roughly 11 million illegal immigrants in the United States.

When they become US citizens, Hispanics remain emotionally attached to their countries of origin. In a poll taken by the Pew Hispanic Center only a few months after the Sept. 11 attacks, at a time when most Americans were feeling deeply patriotic, only 33 percent of citizens of Hispanic origin considered themselves first or only American. Forty-four percent still described themselves as their original, pre-immigration nationality (Mexican, Salvadoran, etc.), and another 22 percent considered themselves first or only “Latino or Hispanic.” It is likely that U.S. citizens of Mexican origin have an even weaker American identity than other Hispanics because they are surrounded by compatriots and their country of origin is so close. When citizens and non-citizens of Mexican origin are taken together, 55 percent consider themselves Mexican, 25 percent Latino or Hispanic, and only 18 percent American. For non-Hispanics, it is unsettling to learn that that so many fellow Americans do not feel a primary loyalty to the United States.

Most Americans believe that a willingness to learn English is a prerequisite to assimilation and full participation in American life, but this does not appear to be a high priority for many Hispanics. According to a 2006 poll conducted by Investor’s Business Daily, only 19 percent of Hispanics spoke mostly or only English at home. Eighty-one percent spoke only or mostly Spanish. Even Hispanics who are comfortable in both languages maintain a strong preference for Spanish; according to a poll by P.C. Koch, nearly 90 percent of bilingual Hispanics get their news exclusively from Spanish-language sources.

A Yankelovich survey in 2000 found that 69 percent of Hispanics said Spanish was more important to them than it was five years ago. In 1997 that figure was 63 percent. During the same period the percentage of Hispanics who expressed a desire to fit into American society dropped from 72 to 64 percent.

In 2003, 44 percent of Hispanics did not speak and read English well enough to perform routine tasks, up from 35 percent in 1992. English illiteracy therefore increased for Hispanics during the decade, whereas it declined for every other major population group. Fifty-three percent of working-age residents in Los Angeles County have trouble reading street signs or filling out job applications in English.

Just how firmly rooted the Spanish language has become in parts of America was clear when 200 students demonstrated in front of Miami Senior High in Miami, Florida. They were protesting the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT), which is the official state test students must pass to get a high school diploma. Their complaint? They had to take the test in English. “We are a Hispanic-based society,” explained Gerrter Martin, who had failed the test twice. “My dreams are over,” said Jessica Duran, who had also failed. State Rep. Ralph Arza promised to introduce legislation to offer the FCAT in Spanish.

Hispanic resentment should not be surprising. “In Miami there is no pressure to be American,” explained Cuban-born Lisandra Perez, head of the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University. “Our parents had to hassle with Anglo society, but we don’t; this is our city,” explained one US-born Cuban. In Miami, this attitude is common. “They’re outsiders,” said one successful Hispanic of non-Hispanics. “Here we are members of the power structure,” boasted another. For people like this, a requirement that high school graduates be able to speak English is an alien and incomprehensible imposition.

The sentiment that Hispanics need no longer adjust to the United States — that the United States will adjust to them — is not limited to cities like Miami and Los Angeles where Hispanics have been present for decades. Salt Lake City, Utah, is hardly a traditional Hispanic stronghold, but it saw its Hispanic population increase 138 percent during the 1990s, from 84,597 to 201,559. Early immigrants tried to learn English and American ways but once there were enough Hispanics to create a parallel society, many gave up the effort. As Archie Archuleta, a city employee who works as an administrator for minority affairs explained, “Most of us don’t push for assimilation. We push for accommodation.”

Dan Pena, an American-born Hispanic who is a chef at a restaurant in Chaska, Minnesota, says it is silly to expect Hispanics to assimilate. “When Europeans came here, home was an ocean apart. For Mexicans, it’s a river, just 60 feet wide.” Jose Salinas, another Mexican immigrant to Minnesota agrees: “I maybe want to stay here. But even if I do, I can’t forget my country, my family, my traditions.”

Dominicans, one of the largest immigrant groups in New York City, feel equally ambivalent about assimilation. As Nelson Diaz who was active in Dominican politics in the city explained: “[W]e are always thinking about going back. The first thing everybody does as soon as they make some money here is to buy a house back home and then a car. Dominicans don’t buy houses here because they don’t think they live here.”

“Rich Latinos remain ambivalent toward America just as much as poor ones,” explains Roberto Suro, formerly of the Washington Post and now at the Pew Hispanic Trust. “In fact, wealth may make it even easier to avoid full engagement with the new land.” Mr. Suro explains the consequences of this sense of detachment. He notes that as many Hispanics as blacks rioted in Los Angeles in 1992 after the verdict in the Rodney King beating trial. Why? “To most [Hispanic] people here, this is still a foreign place that belongs to someone else.”

Some Hispanics insist there is really nothing in America to which immigrants could assimilate anyway. David E. Hayes-Bautista, a sociologist at UCLA, explains that the Hispanic experience shows that “being American simply mans buying a house with a mortgage and getting ahead — there is no agreement anymore on culture, only on economics.” Jorge Ramos, anchorman for the Spanish-language television network Univision explains the absence of anything genuinely American in slightly different terms: “I believe that this country’s two main characteristics are its acceptance of immigrants and its tolerance of diversity . . . That’s what it means to be American.” In other words, what Americans have in common is nothing more than a willingness to have nothing else in common.

This assertion that there is nothing to assimilate to is disingenuous; Hispanics scorn those among their people who assimilate too far. Just as blacks judge each other according to whether they are “black enough,” some Hispanics keep an eye on who is “brown enough.” At one time Linda Chavez was considered as a possible labor secretary in the George W. Bush administration, but came under sharp attack from Hispanics who mocked her as the “Hispanic who doesn’t speak Spanish.”

Nor can a conservative be truly Hispanic. “It’s kind of like if you are black and conservative, there is no way you are really black,” explained Rosemarie Avila, a trustee on the Santa Ana, California, school board. “If you are going to be Latina, you have to be a Democrat. Otherwise you are not truly Latina.” She should know. Other members of the all-Hispanic school board say she is a fake because of her conservative politics.

Hispanics show typical patterns of ethnic nepotism — living among, voting for, and hiring people like themselves. Three Arab employees successfully sued the Azteca chain of Mexican restaurants found in Oregon and Washington state. “The managers at these Azteca establishments made it very clear, by their verbal abuse and physical actions, that they did not want anyone other than those of Hispanic descent working in their restaurants,” explained lawyer Tony Shapiro after the chain settled for an undisclosed sum.

Likewise, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission filed a federal discrimination suit against a Hispanic grocer, Compare Foods, in Charlotte, North Carolina. The store carried a wide range of Hispanic foods, flew Central and South American flags, and greeted shoppers with Hispanic music. The EEOC accused the store of firing long-term workers simply because they were not Hispanic.

Hispanic groups routinely monitor employers, demanding proportionate hiring of fellow Hispanics. Entirely typical was a report by the National Hispanic Leadership Association, an umbrella organization that represents 40 different Hispanic groups, blasting the federal Office of Personnel Management for “failing to promote more government hiring and retention of Hispanic employees.” The report gave the agency a failing grade for its efforts.

As for racial solidarity in housing, a black woman named Aretha Jackson, who worked for the San Fernando Valley Fair Housing Council tracking racial discrimination in apartment rentals, quit her job in disgust, convinced that Hispanic discrimination against blacks was so widespread nothing could be done about it. Sharon Kinlaw, who is with the same organization, pointed out that Hispanic landlords not only kept out non-Hispanics, they often rented only to people from their own country. “You have the Guatemalans versus the Mexicans versus the Salvadorans,” she said. Chancela Al-Mansour, a lawyer with Neighborhood Legal Services of Los Angeles County reported, “I’ve heard people saying, ‘Well, he’s from another state [within] Mexico.’ And the apartment manager only rents to people from the same state in Mexico. Our fair housing laws haven’t even anticipated that.”

Congresswoman Loretta Sanchez of Orange County, California, quickly learned the importance of Hispanic solidarity. When she campaigned under her married name of Brixey, she lost a bid for a seat on the Anaheim City Council. She found that her maiden name of Sanchez has a much better resonance among the voters she needs to reach.

Like blacks, Hispanics have set up a number of organizations to advance specifically Hispanic interests. The oldest is the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), founded in 1929 in Corpus Christi, Texas. As the word “citizen” in its name suggests, it was originally open only to US citizens, and promoted assimilation and patriotism, stressing that Mexican-Americans were American, not Mexican. It supported President Eisenhower’s “Operation Wetback,” which deported one million illegal aliens back to Mexico. LULAC has since changed dramatically. Membership is now open to illegal aliens. It wants Hispanics to speak Spanish, and fights recognition of the central role of English. It supports preferences for Hispanics in hiring, contracting, and college-admissions, and its attitude toward immigration is summed up in the words of a former director Jose Velez: the Border Patrol is “the enemy of my people and always will be.” Needless to say, “his people,” are not the American people.

One of the reasons LULAC stopped pushing for assimilation is that it had to compete with more radical Hispanic organizations that were robbing it of support. The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), set up in 1968 by break-away LULAC members, was modeled on the NAACP-Legal Defense Fund. It has litigated in support of social benefits for illegal aliens, for affirmative action for Hispanics, and against border control, but it appears to have larger aspirations. One of its first executives was Mario Obledo, who has also served as California secretary of health and welfare. In an interview on radio station KIEV in Los Angeles on June 17, 1998, he warned listeners: “We’re going to take over all the political institutions of California. California is going to be a Hispanic state and anyone who doesn’t like it should leave. If they [whites] don’t like Mexicans, they ought to go back to Europe.” That same year, President Bill Clinton awarded Mr. Obledo the Medal of Freedom.

The third major national Hispanic organization, also founded in 1968, has the most explicit name: National Council of La Raza (NCLA). La raza means “the race” in Spanish. Hispanic activists often use this term for Hispanics as a group, just as blacks call other blacks “brothers.” Like the other groups, NCLA promotes official recognition of Spanish, increased immigration, preferences for Hispanics, and amnesty for illegal immigrants.

La Raza was delighted when Alberto Gonzalez was appointed the nation’s first Hispanic attorney general, and held a reception for him in 2005. Janet Murguia, former executive vice chancellor for university relations at the University of Kansas, and president and CEO of La Raza, chaired the event, during which she announced, “We are going to put our people [Hispanics] first.”

Hispanics feel the demographic wind in their sails, and routinely boast about their increasing power. They take it for granted that it is only a matter of time before they push aside the old “Anglo” power structure.

Professor José Angel Gutierrez of the University of Texas explained his views to a Hispanic audience in 1995: “We have an aging white America. They are not making babies. They are dying. It’s a matter of time. The explosion is in our population. You must believe that you are entitled to govern . . . Se estan cagando cabrones de miedo! (They [whites] are sh****** in their pants with fear.) I love it!” In 2004, at a Latino Civil Rights Summit, he added, “We are the future of America. Unlike any prior generation, we now have a critical mass. We’re going to Latinize this country.”

Mike Hernandez of the Los Angeles City Council, echoed the same sentiments in 1996: “Somos Mexicanos (we are Mexicans)! Mexico, some of us say, is the country this land used to belong to! . . . We are the future, we will lead the Western hemisphere!”

Armando Navarro, a professor at the University of California at Riverside, made a similar boast in1995: “[T]ime is on our side, as one people as one nation within a nation as the community that we are, the Chicano/Latino community of this nation. What that means is a transfer of power. It means control.”

“We are everywhere, and there is no occupation or activity in this country that escapes our influence,” says Univision anchorman Jorge Ramos. “This century is ours.” Aida Alvarez, who was head of the Small Business Administration for President Bill Clinton, campaigned for Al Gore against George Bush in 1999, proclaiming that “the 21st century will be a Latino century, no doubt about it.” “The long-anticipated Latino majority has arrived,” says David Hayes-Bautista, director of UCLA’s Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture. “They [Hispanics] will be defining the American dream.”

What do Hispanics means when they talk about transfer of power, of the century belonging to them? Gloria Molina, Los Angeles County Supervisor, explained: “[W]e are politicizing every single one of those new [Hispanic] citizens that are becoming citizens of this country . . . And our vote is going to be important. But I gotta tell you that a lot of people are saying, ‘I’m going to go out there and vote because I want to pay them back.’”

It is jarring for whites to learn that immigrant groups may want “payback” from America.

Hispanics in power are not likely to “celebrate diversity” the way whites are encouraged to do. John Fernandez is a teacher at Roosevelt High School in Los Angeles and spokesman for the Coalition for Chi-cano and Chicana Studies. He wants the staff and the curriculum to reflect the new Hispanic majority and nothing else: “Under the guise of diversity comes a disem-powerment of the Latino community. I don’t see how people unfamiliar with our language and culture and customs can deal with our problems.” His conclusion: “Educating for diversity is a crock.”

Behind this increasing talk of power and control is the indisputable fact that the Hispanic population is growing rapidly, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of the population. Hispanics see sustained mass immigration as the key to eventual dominance, and many therefore fight desperately against any measure to control even illegal immigration.

These sentiments were clearly on display in the spring of 2006. In response to immigration-control measures voted in the US House of Representatives but rejected in the Senate, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators thronged the streets of American cities, demanding amnesty for illegal immigrants, and an end to border controls. A massive, multi-city demonstration on May 1 was dubbed “A Day Without Immigrants,” in which illegal workers were to walk off their jobs, proving by their absence how vital they are. Despite appeals from organizers that they refrain from doing so, many demonstrators carried Mexican or other Latin American flags. Tens of thousands of demonstrators were, themselves, in the country illegally, leading some observers to wonder whether there had ever been a precedent for open, mass demonstration by law-breakers against the laws they have themselves broken.

Large numbers of Hispanics believe that the United States simply does not have the right to control its southern border, and that it is illegitimate even to try. Beginning in 2000, listeners to KROM, the leading Spanish-language radio station in San Antonio, Texas, began calling in to report where they had seen Border Patrol activity. The on-air hosts then broadcast the information so illegal immigrants and border-crossers could avoid those areas. They called agents limones verdes (green limes), because of their olive-green uniforms and the green stripe on their vehicles. Spanish-language stations in other cities have begun doing the same thing.

Even Hispanics whom one would expect to respect the law take the same position. Congressman Luis Gutierrez (D-Ill.), for example, does not like the word “amnesty” to describe legalization of illegal immigrants: “[T]here’s an implication that somehow you did something wrong and you need to be forgiven.” His seems to think that it is the border that is illegal, not crossing it without permission.

American cities with large Hispanic populations commonly refuse to cooperate with federal immigration authorities. In 2006, for example, the predominantly Hispanic Los Angeles suburb of Maywood passed a unanimous resolution to prohibit its police from working with immigration authorities, and rejecting in advance any future federal law that might require such cooperation.

What perhaps best reveals the racial element of Hispanic activism, however, is the reaction to grassroots efforts to stop illegal immigration. The Minuteman Project was founded in 2004 by Californian Jim Gilchrist to help stop illegal border-crossing. In 2005, it gained national attention with “citizens’ border patrols,” which camped out at the border to report illegals. The Minutemen, as they called themselves, did not oppose legal immigrants — who are overwhelmingly non-white — and denounced racism. Their sole aim was to enforce current immigration laws, but Hispanic opponents invariably called them “racist.” The League of United Latin American Citizens, for example, defined the Minutemen on their web site as “racists, cowards, un-Americans (sic), vigilantes, domestic terrorists.”

Juan Maldonado, the Democratic Party Chairman of Hidalgo County, Texas, speaks in equally intemperate terms: “[T]he Minutemen are the epitome of hate, fear and ignorance. We are unified to stop this racist movement from entering our region.”

In October 2006, demonstrators rushed the stage and prevented founder Jim Gilchrist from speaking at Columbia University. They shouted down a black spokesman for the movement, Marvin Stewart, calling him a “black white supremacist.” As police began escorting people out of the auditorium, indicating that the event had been canceled, they began chanting “Si, se pudo. Si, se pudo. (Yes, we could.)”

Hispanics see their interests in openly racial terms, and think of their growing numbers and influence as a triumph for their race. This is why they call a racially neutral group like the Minutemen “racists” and “white supremacists.” This language reveals their own racial/ethnic chauvinism, not that of people who oppose illegal immigration.

The same reflexive racialism was behind a 2006 confrontation at Washington State University between John Streamas, a Hispanic assistant professor of comparative ethnic studies, and a white student named Dan Ryder. The two argued about illegal immigration, and Prof. Steamas called Mr. Ryder a “white shit-bag.” Mr. Ryder complained that someone who teaches in a department that stresses tolerance and diversity should not use such language. Prof. Streams was unapologetic, saying “I don’t care about the hurt feelings of one white person. The feelings of one little hurt white boy who’s got all his white-skinned privilege are nothing . . .” Prof. Steamas clearly saw an argument about immigration in racial terms.

Some local authorities are desperate to do something about the overcrowding, loitering, and drain on social services often associated with an influx of illegal immigrants. Predictably, Hispanics attack such measures as “racism.” Hazleton, Pennsylvania, was among the first towns to pass an ordinance that would fine landlords or employers who rent to or hire illegal immigrants. Anna Arias, a Hispanic who served from 2003 to 2005 on the Pennsylvania Governor’s Advisory Commission on Latino Affairs, warned that the ordinance would make Hazleton “the first Nazi city in the country.” When other cities have debated similar ordinances, council meetings have been swamped with Hispanic activists making similar charges.

Many Hispanic voters, therefore, support candidates strictly on the basis of their position on Hispanic immigration. Many vote Democratic for other reasons as well, but some who would ordinarily support Republicans have threatened to abandon the party if it takes a stand against illegal immigration. Hispanic pastors have traditionally supported the GOP because of its position on abortion and same-sex marriage, but ethnic identity comes first. Rev. Danny de Leon is pastor of Templo Calvario in Santa Ana, considered the biggest bilingual Hispanic church in America. “A lot of people are saying, ‘Forget being a Republican. I want to go to the Democratic Party,’” he explained. “It’s a shame that one issue [immigration] has divided many of us that have been in the Republican Party for a long time.”

Pastor Luciano Padilla, Jr. of the Bay Ridge Christian Center in Brooklyn used to take the Republican position on social issues, but turned against Republicans when they began to oppose illegal immigration and amnesty. “We will have to look at where we put our allegiance in the future,” he explained. Rev. Luis Cortes, Jr. is a Republican who founded the annual National Hispanic Prayer Breakfast that featured President George Bush every year from 2002 to 2006. His Philadelphia-based Esperanza USA claimed a national affiliate network of more than 10,000 churches. He, too, reconsidered his support for Republicans: “If voting is about personal interest, how are Hispanics to vote? They will vote against those guys [who oppose illegal immigration],” he said. The Republicans may be right about everything else, but what matters most to these men is the racial interest they have in bringing more people like themselves into the country.

Mexico and American Hispanics

The 30 million American residents of Mexican origin show considerable ambiguity about the United States. It will be recalled that according to the Pew Hispanic Center, only 18 percent think of themselves first and foremost as American. The rest show in a variety of ways where their loyalties lie.

The most obvious and widespread way is by sending money outside the country. In 2005, American Hispanics sent an estimated $20 billion to Mexico, making immigrant remittances the second largest source of foreign exchange for Mexico, after oil imports and ahead of tourism. These remittances are so important to the economy that former Mexican president Vicente Fox called Mexicans living in the United States “national heroes.” In 2005, immigrants sent $12 billion to Central America and $22 billion to other South American countries, which means that immigrants sent approximately $55 billion out of the US economy.

A lot of this money goes straight to Mexican governments at various levels. In 2004, there were an estimated 500 Mexican federations or mutual aid societies in the United States that raised money for Mexican home towns or home states. That year, they helped fund 1,435 public works projects in 300 cities and towns. These included installing street lights, paving dirt roads, putting in sewers.

For states like Zacatecas that send a lot of workers to the United States, these citizen groups are a vital source of revenue. When the officers of the Federation of Zacatecas Clubs in North Texas were sworn in in 1997, Zacatecas Lt. Governor Jose Manual Maldonado Romero was on hand to encourage contributions. “You may be here, but your hearts, your blood, part of your spirit is over there with us,” he said.

Seventy-six percent of the population of Santa Ana, California, is Hispanic, and Mexican consul Luis Miguel Ortiz Haro encourages people from all parts of Mexico to form associations to send money home. In 2006, there were associations for at least the states of Michoacán, Sinaloa, and Nayarit. As Nayarit native Dely Delegado explained during a festival that attracted the state’s governor: “It was like Nayarit was here. We saw our people and our governor. They even had dancers doing the estampa, and you can’t find that in another state.”

Many Mexicans send more money home to Mexico than they spend in the United States. As John Herrara of the Latino Community Credit Union, which has five branches in North Carolina, explains, “[T]hese working-class folks are sending real money back home.”

These working-class Hispanics also happen to be the ethnic group least likely to have medical insurance, and to require treatment at public expense. Thirty-three percent of Hispanics are uninsured, vs. 11 percent of whites and 20 percent of blacks. The majority of immigrants from Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala lack medical insurance.

Many Americans question the priorities of people who regularly send money outside the United States rather than spend it here. They question the morals of people who then throw themselves on public charity when they go to the hospital. Curiously, the Federal Reserve Bank has established Directo a Mexico, a program in cooperation with the Mexican central bank, to make it easier and cheaper for Mexicans to send money home, regardless of their legal status.

Mexicans show their deepest loyalties in other ways. Immigrants from other countries naturalize after an average of seven years of eligibility, but until recently, Mexicans waited an average of 21 years before renouncing Mexico and becoming American. “For many Mexican natives, it was like you’re giving up your life, your heritage, if you apply to become an American,” said Leonel Castillo, a federal commissioner of immigration and naturalization under President Jimmy Carter.

In 1998, however, Mexico eased the pain, and permitted its citizens to retain Mexican nationality even if they naturalize. Under the new regulations, Mexicans who had already lost their citizenship by naturalizing even had the right to reclaim it by applying at a Mexican consulate. One who took immediate advantage of this offer was 59-year-old Magdalena Flores Gonzalez. She had come to America 33 years earlier, had four children in the United States, and became a citizen in 1992. “We were born in Mexico,” she said, gesturing to others who were in line at the consulate to get their citizenship back. “This is all about going back to a reality, the reality that we are Mexicans.” Ericka Abraham Rodriguez felt the same way. For her, naturalization in 1991 was a betrayal. “When I gave up Mexican nationality, I felt like a lost person. You lose part of your roots, part of your history.” She, too, was glad to become Mexican again in law as well as spirit.

By 2006 nearly 100,000 US citizens had reclaimed Mexican nationality, in a gesture many would think gives the lie to their oath of naturalization, in which they swore “absolutely and entirely [to] renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state or sovereignty.” Since 1998, the vast majority of Mexicans who naturalized also retained Mexican citizenship, which suggests that their first act as an American citizen was perjury.

Spanish-language media encourage Hispanics to become US citizens — but not really become American. Early in 2007, newspapers and television joined church groups and Hispanic activists in a campaign called Ya Es Hora. ¡Ciuda-dania! (It’s time. Citizenship!) La Opinion, a Los Angeles newspaper, published full-page advertisements explaining how to apply for citizenship, and the Spanish-language network Univision’s KMEX television station in Los Angeles promoted citizenship workshops extensively on the air. A popular radio personality named Eddie Sotelo ran a call-in contest called “Who Wants to be a Citizen?” in which listeners could win prizes by answering questions from the citizenship exam: What are the three branches of the U.S. government? Who signs bills into law? What is the Fourth of July? Legal resident William Ramirez explained to a reporter why he wanted to become a citizen: “I can do better for my people. I can help with my vote.”

In January 2006, Mexican pop singer and actress Thalía (her real name is Ariadna Thalía Sodi) became a naturalized American but reassured her Mexican fans that she didn’t really mean it. Speaking in Spanish, she explained: “This morning I acquired United States citizenship. Nevertheless, under the laws of my country, Mexico, I can also have Mexican citizenship . . . Just like some of my Latino friends such as Salma Hayek, who is just as Mexican as I, and Gloria and Emilio Estefan, among others, I feel that this step will give me the opportunity to contribute to and support even more the Latin community in the United States. I am of Mexican nationality, and I will always be a proud Mexican in heart and soul.”

There are many like her, who remain Mexican in heart and soul, and some have surprising last names. George P. Bush, nephew of President George W. Bush is only half Mexican — his father, Florida governor Jeb Bush, married a Mexican-born woman — but when he campaigned for his uncle in 2000 he sounded altogether Hispanic. He appeared in a television ad in which he said, in fluent Spanish, “I’m a young Latino in the United States and very proud of my bloodline. I have an uncle that is running for president because he believes in the same thing: opportunity for everyone, for every Latino.”

At a Republican rally he again explained in Spanish that his mother had instilled in him the values of Cesar Chavez, who organized Mexican farm workers. “She told me we have to fight for our race, we have to find the leaders who represent us,” he said. About his uncle the candidate, he said, “This is a president who represents the diversity of our society, who we can count on to change the Republican Party to represent our views.” Needless to say, “our race” was la raza,and “our” views were those of Hispanics.

George P. Bush does not have dual citizenship — not yet, anyway — but some of those who do take what some might consider liberties. In 2003, four Americans living in the United States ran for at-large seats in the Mexican Congress. On July 6, Manuel de la Cruz of Norwalk, California, became the first American citizen to win a seat in the Congreso de la Union. The next year, 2004, he was elected to the legislature of the Mexican state of Zacatecas. When he was naturalized 33 years before that, the Los Angeles resident took the oath of allegiance. Each time he took his seat in a Mexican legislature, Mr. de la Cruz swore an oath of allegiance to Mexico.

In the 2003 elections Jose Jacques Medina of Maywood, California, lost by just a few votes. Mr. Medina, who fled to the US in the 1970s because of alleged “political crimes,” said that if he had won a seat he would keep his home in Maywood. “I am Mexican,” he explained, “but I will always live in California, fighting for the emigrant Mexicans who live here.” Both he and Mr. de la Cruz favored giving Mexicans in the United States formal representation in the Mexican congress. After all, they argued, 20 percent of the country lives in el norte, and they need official representatives.

Because so many Mexicans living in the United States can vote in Mexican elections, politicians routinely cross the border to campaign. There was considerable discussion about making the United States a formal voting district for the presidential election in 2006, but Mexican Foreign Relations Secretary Luis Ernesto Derbez opposed the idea. He was not worried that Americans would be insulted if their country were treated like a Mexican province. He was afraid American authorities might use Mexican election day to identify and catch illegal immigrants who turned out to vote.

Other Mexicans show their loyalties in more visceral ways. On Feb. 15, 1998, the US and Mexican national soccer teams met at the Los Angeles Coliseum. The largely Hispanic crowd was overwhelmingly pro-Mexican. There were boos and catcalls during the National Anthem, and Hispanics threw beer and trash at the American players before and after the match. Anyone in the stands who supported the American team was hooted at, and some were punched or spat on. Hispanics sprayed beer and soda on a Mexican-American man who held a small American flag. The game could have been played in any American city with a large Hispanic population; the Mexican team would have had the home-field advantage.

In another demonstration of loyalty, Hispanic legislators pushed through a bill in 2000 establishing Cesar Chavez Day as a state holiday in California. In 2001, the City Council of Dallas, Texas, nearly did away with Presidents Day to make room for Cesar Chavez Day, but in the end added the farm labor organi-zer’s name to Labor Day. Likewise in 2001, Hispanic legislators introduced a bill in the New Mexico legislature that would have officially changed the state’s name to Nuevo Mexico. When the bill was defeated in committee, sponsor Miguel Garcia said “covert racism” may explain the defeat. Congressman Joe Baca of California and other Hispanic congressmen have regularly introduced bills in the House that would make the Mexican holiday Cinco de Mayo an American national holiday. These bills have gone nowhere — so far.

Perhaps the quaintest sign of Mexican loyalty is the inextinguishable desire to go home some day, even if it’s in a box. When an illegal immigrant dies in the United States, their families nearly always manage to have the body shipped home, but even the majority of naturalized US citizens report that they want their final resting place to be Mexico. In 2002, more than 1,200 corpses left for Mexico from Los Angeles airport alone, despite the $1,500 fee funeral homes charged for shipping a body. As one Mexican farmer explained, emigrants “don’t want to lose their identity as a Mexican. What they want is to find a way back to be here, even if they come back dead.”

If some Mexican-Americans have their way, they will not have to go back to be buried; Mexico will come to them. What is called the Reconquista movement aims to break the Southwest off from the United States and reattach it to Mexico or even establish it as an independent, all-Hispanic nation. In historic terms, it would reverse the territorial consequences of the Mexican-American war. Reconquista is generally promoted by the best-educated Hispanics, many of whom were born in the United States.

Charles Truxillo, a professor of Chicano studies at the University of New Mexico, thinks Republica del NorteX would be a good name for a new Hispanic nation. The Republic of the North would contain all of California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas and the southern part of Colorado. Its capital would probably be Los Angeles. The Albuquerque-born Prof. Truxillo says the new nation is “an inevitability,” and should be created “by any means necessary.” He doubts violence will be necessary, however, because shifting demographics will make the transition a natural one. “I may not live to see the Hispanic homeland,” he says, “but by the end of the century my students’ kids will live in it, sovereign and free.”

Juan Jose Peña, Hispanic activist and vice chairman of the Hispanic Roundtable of New Mexico agrees with Prof. Truxillo, adding, “I’ve studied lots of civilizations. The United States is just like any other empire. It’s not going to live forever. Eventually it will break down because of stresses.”

Armando Navarro, Hispanic activist and professor at the University of California at Riverside is another Reconquista advocate, noting that if current social and demographic trends continue, secession is inevitable. “One could argue that while Mexico lost the war in 1848, it will probably win it in the 21st century, in terms of the numbers,” he explained. “A secessionist movement is not something that you can put away and say it is never going to happen in the United States,” he adds. “Time and history change.”

Xavier Hermosillo, a prominent businessman and leader of a Hispanic activist group in Los Angeles, explained that “we’re taking it [California] back, house by house, block by block.” He adds: “People ought to wake up and smell the refried beans.”

Probably the best known Reconquista organization is the Chicano Student Movement of Aztlan, better know by its Spanish acronym of MEChA. The word Aztlan in the organization’s name means “the bronze continent,” and is the name activists plan to give the new nation they carve out of the United States. One of its founding documents, El Plan de Aztlan, describes white people as “the brutal ‘gringo’,” and calls for Mexicans to reclaim “the land of their birth” and “declare the independence of our mestizo nation.” The group’s motto is Por la Raza todo. Fuera de La Raza nada: “For the race, everything. For those outside the race, nothing.” Founded in 1969 at the University of California at Santa Barbara, MEChA now has chapters on nearly every California college campus and in most high schools in the state. It has a considerable presence in other Western states as well. The official symbol of MEChA is an eagle holding an Incan battle axe and a lighted stick of dynamite. The slogan that goes with the symbol, Hasta la victoria, siempre! (Until victory, always!) was a favorite of Fidel Castro and the Cuban revolution.

On some campuses, conservatives have called attention to MEChA’s racially divisive message, and Stanford students voted by a narrow margin to withhold university funding from the group. At the University of California at Los Angeles, the campus Republicans tried at least to get the group to denounce the explicitly secessionist El Plan de Aztlan, but it refused. “We will stand by the ‘El Plan de Aztlan’ because it has guided us,” MEChA chairwoman Elizabeth Alamillo explained.

Many Mexican intellectuals eagerly anticipate Reconquista. According to one newspaper report:

The Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska affirmed today that Mexico is presently recovering the territories lost in the past to the United States, thanks to emigration: ‘The people of the poor, the lice-ridden and the cucarachas [cockroaches] are advancing in the United States, a country that wants to speak Spanish because 33.4 million Hispanics impose their culture.’ Ms. Poniatowska added that ‘this phenomenon . . . fills me with jubilation, because the Hispanics can have a growing force between Patagonia and Alaska.’

Even Mexican government spokesmen speak the language of irredentism. At a symposium in Los Angeles on the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which marked the end of the Mexican-American War, the Mexican consul general, Jose Angel Pescador Osuna observed, “Even though I am saying this part serious and part joking, I think we are practicing la Reconquista in California.”

In 2005, Reconquista sentiment got an unusual public airing when 75 billboards appeared in Los Angeles advertising Spanish-language KRCA-TV. The billboards showed two newscasters in front of the downtown skyline, with “Los Angeles, CA” written above them. The “CA” was crossed out, and “Mexico” was stamped over it in bright red letters. Below, it said in Spanish: Tu ciudad. Tu equipo. (Your city. Your team.) Even a few gringos got the message. “The joke here is, ‘We’re taking back California,’” explained Stuart Fischoff, who teaches media psychology at California State University at Los Angeles. “Underneath the joke is part of the truth.”

Part of the great appeal Fidel Castro has long enjoyed in Mexico is his unwavering support for Mexican irredentism. In a 1997 speech in Mexico City, he renewed his call for the United States to return Texas, California, Arizona, and New Mexico. He said Americans are “terrorized” when Mexicans cross into what is in fact their own territory.

The spirit of conquest need not be limited to the Southwest. Mass immigration, and the unwillingness of native-born Americans to insist on assimilation by newcomers leaves the impression the whole country is up for grabs. Riverside, New Jersey, is one of a handful of American cities that have tried to pass ordinances to discourage hiring or renting to illegal immigrants. Rev. Miguel Rivera, president of the National Coalition of Latino Clergy & Christian Leaders, noting that legal residency is not required to purchase property in the US, said illegal aliens would retaliate by buying rather than renting. New owners would welcome other illegals, who would eventually dominate through sheer force of numbers. “Riverside is going to be ours,” he said.

The Official Mexican View

It is official Mexican government policy to urge Mexicans living in the United States to remain loyal to Mexico. This policy applies broadly to all naturalized and even US-born citizens of Mexican origin, but government spokesmen direct their strongest efforts towards Mexican-Americans who hold elected office. In 1995, for example, then-president of Mexico Ernesto Zedillo himself told a group of Mexican-American politicians, “You’re Mexicans — Mexicans who live north of the border.” Two years later in Chicago, he took the same message to the Hispanic advocacy group, the National Council of La Raza. He “proudly affirmed that the Mexican nation extends beyond the territory enclosed by its borders and that Mexican migrants are an important — a very important — part of this.”

The administration of Vicente Fox continued the policy of ensuring that Mexican-Americans remained Mexican. In 2002, his government established the Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior (Institute for Mexicans Abroad) to promote “a more comprehensive approach” to promoting Mexican loyalty. A primary function was to invite American elected officials of Mexican origin to Mexico, to deepen their Mexican identity. In October 2003, for example, the Instituto invited 30 American state legislators and mayors for two days in Mexico City, where they met Mexican legislators, ministry officials, scholars, and advocates for immigrants. The institute had plans to bring 400 Mexican-American lawmakers and community leaders on similar trips in 2004.

The Instituto also sends representatives to the United States. Jacob Prado, counselor for Latino affairs at the Mexican Embassy, explained to the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials that it was in “Latino officials like yourselves that thousands of immigrants from Mexico find a political voice.” He went on to explain: “Mexico will be better able to achieve its full potential by calling on all members of the Mexican Nation, including those who live abroad, to contribute with their talents, skills and resources.” American elected officials are still “members of the Mexican Nation.”

One Instituto official, Juan Hernández, typifies its approach. Born in the United States, and therefore a US citizen, Mr. Hernández was at one time a professor at the University of Texas at Dallas, but makes no secret of where his real loyalties lie. On the web page of the President of Mexico he reported in 2002 that he had “been commissioned to bring a strong and clear message from the President to Mexicans abroad: Mexico is one nation of 123 million citizens — 100 million who live in Mexico and 23 million who live in the United States.” On ABC’s Nightline on June 7, 2001, he was candid about his goals: “I want the third generation, the seventh generation, I want them all to think ‘Mexico first.’” He has also explained that Mexican immigrants are unlike Europeans because they “are going to keep one foot in Mexico” and that they “are not going to assimilate in the sense of dissolving into not being Mexican.”

Adolfo Aguilar Zinser, who later became national security advisor to Vicente Fox, described the basic thinking of all Mexican administrations. In an article in the Mexican newspaper El Siglo de Torreon, he wrote that the Mexican government should work with the “20 million Mexicans” in the United States to advance Mexican “national interests.”

All political factions in Mexico are united in the view that the US-Mexican border is illegitimate, and that Mexicans have the right to cross it any time. Former president Vicente Fox’s official view was that any measures the United States took to catch or deport illegal immigrants were a violation of human rights. Felipe Calderon, who succeeded him in 2006, shared that view, adding, “like many . . . I have cousins, uncles, in-laws who are undocumented and live in the United States.” Mexican Interior Secretary Santiago Creel once complained, “It’s absurd that (the United States) is spending as much as it’s spending to stop immigration flows that can’t be stopped . . .” When he took over in 2004 as the man in charge of border relations with the United States, Arturo Gonzalez Cruz explained that his ultimate goal was to see the border disappear entirely.

At the time of the “A Day Without Immigrants” demonstration in May, 2006, Mexicans showed their solidarity by organizing what was to be a massive boycott of American products. Mexican unions, political and community groups, newspaper columnists and a number of government officials issued the call. “Remember, nothing gringo on May 1,” said a typical e-mail message, urging people not to patronize McDonald’s, Burger King, Starbucks, Sears, Krispy Kreme or Wal-Mart. The goal was to pressure Congress into looser border control and amnesty for illegal immigrants.

In 2004, the government distributed millions of free copies of The Guide for the Mexican Migrant, a comic-book-format set of instructions on how to sneak into the United States. It explained what to pack for a desert or river crossing, techniques for surviving extremes of heat or cold, and how to avoid the Border Patrol. Once in the United States, it advised Mexicans to keep their heads down and not attract attention.

Grupo Beta is a government-funded organization set up in the early 1990s to help illegal border-crossers. It maintains hundreds of staging areas just south of the border, marked with blue pennants to indicate that drinking water is available. Mexicans planning a run for the border can flag down its bright orange trucks any time for help. Grupo Beta frequently gives lectures on safety and concealment, typically ending them with the words, “Have a safe trip, and God bless you!”

The Mexican state of Peubla has gone even further. In late 2006, it announced an innovative program to keep emigrants from getting lost when they cross the border illegally. Jaime Obregon, the coordinator for the Commission for Migrants, said the state would give handheld satellite navigation devices to anyone who registered as a border-crosser. “Our intention is to save lives,” he explained, saying he expected the state to hand out 200,000 devices during the following year.

The view that Mexicans have a natural right to enter the United States explains the vitriol that met American discussions in 2006 about ways to stop illegal crossings, and an eventual Congressional vote to build a wall along certain parts of the Mexican border. President Vicente Fox called the plan for a wall “disgraceful and shameful,” and promised that if it were ever built it would come down like the Berlin Wall. Interior Ministor Santiago Creel boasted that “there is no wall that can stop” Mexicans from crossing into the US. Foreign Secretary Luis Ernesto Derbez warned that “Mexico is not going to bear, it is not going to permit, and it will not allow a stupid thing like this wall.” He even said he would ask the United Nations to look into the American plan and declare it illegal.

Ordinary Mexicans were just as outraged. “It’s against what we see as part of our life, our culture, our territory,” exclaimed Fernando Robledo of the state of Zacatecas. “Our president should oppose that wall and make them stop it, at all costs,” said 26-year-old Martin Vazquez of Mexico City. Jose Luis Soberanes, head of the Mexican National Human Rights Commission, didn’t think the government was being forceful enough. “I would expect more energetic reactions from our authorities,” he said. “It’s preferable to have a more demanding government, more confrontation with the United States.”

Other Latin American countries were equally outraged. Guatemalan Vice President Eduardo Stein said a wall would be “absolutely intolerable and inhuman.” The foreign ministers of Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama and the Dominican Republic all gathered in Mexico City to denounce the American measures and to coordinate strategy to make sure the border remained open to illegal immigrants.

Latin American countries, themselves, carefully control their borders, but their governments insist that the United States remain open. In an act of unusual candor, Mexican President Felipe Calderon acknowledged in 2006 that in light of the harsh measures Mexico takes against illegal immigrants from Central America it was inconsistent to complain about American border controls. In 2005, Mexican authorities caught nearly a quarter million illegals, mostly from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

Mexico probably takes a more forceful and even high-handed interest in domestic American policies than does any other country in the world. Mexican consular officers work closely with Hispanic organizations in the United States to press for amnesty, free medical treatment, welfare benefits, driver’s licenses, and in-state university tuition for illegal aliens. The Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Exterior keeps databases of Mexican activists who can be counted on to pack the galleries of state legislatures and city councils whenever there is a vote that might affect immigrants. Such a crowd was on hand during the California legislature’s debates in 2003 over whether to grant driver’s licenses to illegals. When an assemblyman complained, “This bill paves the way to Aztlan!” everyone in the gallery stood up and applauded. When the city council of Holland, Michigan, debated whether to accept Mexican consular identification cards issued to illegal immigrants, a Mexican official brought a crowd of compatriots. They caused such a disturbance the city council was unable even to deliberate.

As noted above, in May 2006, Hispanics in America mounted massive demonstrations against proposed measures to control immigration. The Mexican legislature issued a declaration of support for the demonstrators, and voted to send a delegation to Los Angeles to show solidarity. These gestures received the overwhelming support of every political party.

Likewise, when California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger denounced a plan to grant temporary driver’s permits to illegal immigrants the assembly of Baja California promptly voted him “persona non grata,” theoretically barring Gov. Schwarzenegger from visiting the neighboring Mexican state.

The Mexican government is careful to see that Mexicans living in America receive every possible benefit available to them. A few welfare programs are closed to illegal immigrants but Food Stamps are not. Some illegal immigrants hesitate to apply for them for fear their status will be discovered and they will be deported. Mexican consul Luis Miguel Ortiz Haro of Santa Ana in Orange County, California, went on Spanish-language television to tell Mexicans it was safe to apply. “This program is not welfare,” he said. “It won’t affect your immigration status.” More than 1,200 people applied for Food Stamps the next day.

No other country so frequently intervenes in the interests of its citizens. In 2000, for example, the Mexican consul in Atlanta urged Hispanics to start a national boycott of any company that does not offer services in Spanish. In San Diego, the Mexican consul officially urged Mexicans who work as janitors to join a class-action lawsuit against California’s supermarket chains. “This lawsuit is important because it involves large numbers of our nationals, and because it insists that their rights be respected regardless of their legal status,” said Luis Cabrera Cuaron. Most Americans have no idea of the extent to which Mexico criticizes and tries to influence American affairs.

Every Mexican institution nurtures unfavorable views of the United States, and immigrants bring with them the sentiments they learned as children. As one American observed:

“I was visiting the Museum of National History in Mexico City where I observed a class of perhaps 40 10-year-old school kids sitting on the ground in front of a huge mosaic map that was labeled ‘Mexico Integral,’ or ‘Greater Mexico.’ Their teacher expounded on how the Norteamericanos stole half of Mexico in 1847 in what the Mexicans refer to as the North American Intervention. The map showed Mexico to include Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, California, most of Idaho, and Oregon and Washington up to the Alaska panhandle.”

According to one poll, 58 percent of Mexicans believe the southwestern United States rightfully belongs to them, and 57 percent believe they have the right to cross the border without US permission. Mexicans also assume that America is not serious about border control or citizenship. As Jesus Cervantes, director of statistics for Mexico’s Central Bank explained, “There have been amnesties and reforms before, and they will continue to occur periodically.”

The illegal crossing into America is so much a part of the Mexican psyche that in Ixmiquilpan, in the central state of Hidalgo, there is a theme park devoted to reproducing the experience. At $15.00 a head, Mexicans can spend an evening crossing a fake Rio Grande, squishing through mud while a fake people-smuggler in a ski mask shouts “Hurry up! The Border Patrol is coming!” Advertisements for the theme park offer the chance to “Make fun of the Border Patrol!” and to “Cross the Border as an Extreme Sport!”

Many Mexicans believe the United States cannot function without them. In a 2004 Mexican film called A Day Without a Mexican: The Gringos Are Going to Weep, all the Hispanics in California suddenly disappear. In just 24 hours, pompous, helpless whites find that schools have closed, grocery shelves are empty, and piles of garbage clog the streets. Martial law is declared. The Hispanics miraculously reappear the next day, and are greeted with hugs and kisses — even by the Border Patrol.

The Mexican view of the United States is a mixture of historic resentment, envy, and contempt for a nation that submits to insult and cannot control its borders. These sentiments start at the top. Near the end of his term, former president Vicente Fox, who frequently boasted of his close friendship with President George W. Bush, explained to Mexicans why they should be thankful for their heritage. “We are already a step ahead, having been born in Mexico,” he said. “Imagine being born in the United States; oof!”

When Mexicans in the United States get in trouble with the law, the usual explanation is that they were corrupted by America. As Jesse Diaz of the League of United Latin American Citizens explained, “They’re picking up those bad habits of cheating, of drinking, and drugs” after they arrive, adding that US popular culture undermines the “conservative Catholic values” they brought with them from Mexico.

This is essentially the average Mexican view. A 2006 Zogby poll gave the following results: 84 percent of Americans said they had a positive view of Mexicans, but only 36 percent of Mexicans had a positive view of Americans. Eighteen percent of Americans thought Mexicans were racist, while 73 percent of Mexicans thought Americans were racist. Forty-two percent of Americans thought Mexicans were honest, but only 16 percent of Mexicans thought Americans were honest.

Mexicans are devoted soccer fans, and sports seem to bring out their true feelings. On February 11, 2004, the American Olympic soccer team played a qualifying match against Mexico in the Mexican town of Guadalahara. The crowd drowned out “The Star Spangled Banner” with their boos, and shouted “Osama! Osama! Osama!” as the US players left the field. This only repeated the treatment the Americans got just a few days earlier when they played a match in Zapopan: hooting down the national anthem, booing when the Americans scored, and shouting “Osama! Osama!” However, that game was not even against Mexico. The Americans were playing Canada.

Why Are We Passive?

With the possible recent exceptions of Iran and North Korea, no other country treats us with such contempt. Government officials openly subvert our policies, ordinary people insult us, and many Mexicans even appear to have designs on part of our territory. Why are we so passive? Why do American universities say nothing when Hispanic faculty and students openly advocate breaking up the United States? Why do no politicians complain when many Hispanics send home hundreds of dollars every month — and then seek medical treatment at taxpayer expense? Why are we silent when Mexicans take US citizenship while openly proclaiming their loyalty to Mexico? Why do most journalists and politicians tacitly agree with the Hispanic view that immigration control is “racist”?

Much of the answer lies in the fact that Hispanics are not white, and that most whites are so fearful of being called “racist” they dare not take a stand against any non-white group. Let us imagine that France were sending us millions of poor, uneducated Frenchmen who made no effort to learn English, who celebrated French holidays rather than American holidays, who sent money out of country but demanded free services, who expected ballot papers and school instruction in French, who ignored our immigration laws, who insisted on hiring and college admissions preferences because they offered us “diversity?” What if some of them talked openly about taking over parts of the United States and kicking out the rest of us? Would our press and politicians remain silent?

What if the French government openly encouraged all this? What if it offered French-American elected officials free, loyalty-boosting trips back to France, and encouraged French-Americans everywhere to work and vote for French rather than American interests? What if the French jeered at our national anthem and chanted “Osama, Osama” when our athletes took the field?

Americans would be furious. We would recall our ambassador. We would deport every French illegal, and severely limit further immigration from France. There would be calls to strip naturalized Frenchmen of US citizenship — particularly if they had shown their true loyalties by maintaining French citizenship.

Let us not forget how angry Americans were when France opposed the invasion of Iraq. That affront to our pride was nothing compared to what we have suffered every day for decades at the hands of Mexicans and their government. If the French were to treat us as Mexicans do, there would be universal outrage and immediate countermeasures because we would not be paralyzed by the fear of being called racists.

With Hispanics, however, not only does race make us powerless to resist, race is part of what drives their refusal to assimilate and fuels their contempt for our culture and our interests. Demands, insults and loyalties are ultimately in the name of la raza, and that is what makes them so durable and so dangerous — and makes it impossible for us to respond as any normal, healthy nation would respond to similar provocations.

Another reason for our passivity is the fact that Hispanics are now nearly 15 percent of the population, and their numbers are growing rapidly. Politicians from both parties say they cannot afford to alienate Hispanics because of their increasing power at the ballot box. They do not seem to recognize the danger of currying favor with a voting bloc whose loyalties may not even lie with our own country. American citizens who place foreign interests over those of the United States do not deserve the same political consideration as loyal Americans. What if there were a sharp crisis with Mexico? Is there any doubt which side Mexican-Americans — citizens or not — would take?

It is already nearly impossible to discuss immigration rationally, or even enforce laws that are on the books. If we are already afraid to take measures that would antagonize 15 percent of the population, how likely are we to be able to act in our own interests if Hispanics become 20, 30, or even 40 percent of the population?

The number-one political goal of Hispanics is amnesty for illegal immigrants and yet more Hispanic immigration. If American politicians refuse to set policy according to national needs, if they sacrifice the longer-term interests of America for the short-term political gain of placating Hispanic voters, they will eventually find themselves pushed aside by sheer force of numbers.

Like those of blacks, Hispanic group interests are narrowly defined and do not leave much room for broader, national interests. There is no sign that as Hispanics increase in numbers they are expanding their horizons to include these broader interests.

After decades of accepting sole responsibility for the failure of blacks to become full-fledged Americans, whites should have learned that multiracialism is an endless Calvary of accusations, resentments, demands, failures, and conflicts. It was the worst of folly needlessly to have established yet another minority to tread this bitter and all-too-familiar ground.

More and more Americans recognize that we are, in effect, giving our country away to foreigners who care nothing for us or for our traditions. It is this largely inchoate realization that drives ordinary Americans and even a few in Congress to see that we face a choice that is nothing short of a civilizational crisis: Will we remain part of the West or will we leave to our grandchildren a shapeless, Third-World jumble in which the men and culture of Europe are on their way to oblivion? We still have a choice if only we have the will.

[Editors Note: A version of this essay appears in Jared Taylor’s book White Identity, available for purchase at the American Renaissance online store.]