Criminal Aliens

Roger McGrath, American Renaissance, October 2005

Kevin J. Mullen, Dangerous Strangers: Minority Newcomers and Criminal Violence in the Urban West, 1850-2000, Palgrave MacMillan, 2005, 224 pp.

Dangerous Strangers is a must read for anyone interested in crime, urban and immigrant studies, or San Francisco. Author Kevin Mullen was a San Francisco cop for nearly 30 years, retiring as deputy chief of the department. He knows the city intimately and has studied its history thoroughly. He was born in an Irish neighborhood in the Noe Valley section of San Francisco in 1935, and got on the force in 1959 after serving in the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division. Central casting could not have supplied a more stereotypical Irish cop. With a mug that has the Emerald Isle written all over it and a six-foot two-inch heavy-boned frame, the red-faced Mullen could be mistaken for nothing else.

With a sharp mind and a devotion to duty he rose rapidly through the ranks, all the time making mental notes on San Francisco, people, and crime. When he retired, he indulged his intellectual curiosity by researching crime in pioneer San Francisco, which resulted in his first book, Let Justice Be Done: Crime and Politics in Early San Francisco (1989). In it, Mr. Mullen clearly demonstrated that crime and violence in the city were not so much a consequence of the wild rush for gold but the conflict created by disparate groups with different values occupying the same space. His new book, which reflects more than a decade of research, develops a similar theme but over a century and a half. The breadth and depth of the study is spectacular and should firmly establish Kevin Mullen as the authority on crime and violence in San Francisco. At the same time, the book is full of interesting anecdotes and colorful descriptions that could hardly be surpassed by a detective novel.

Most importantly, especially in today’s politically-correct climate, Mr. Mullen tells the story of immigrant and minority crime without omissions, euphemisms, or convoluted rationalizations. Dangerous Strangers is simply the straight scoop. With a focus principally on homicide, Mr. Mullen concludes that high rates of criminal violence can be attributed more to the characteristics of a particular immigrant group than to its reception or treatment. As Mr. Mullen puts it, “It is also found that the violent behavior can often be traced to behaviors emerging from the newcomers’ culture — more than is generally conceded — than to discrimination on the part of the host society.” He further concludes that the way the police operate affects the level of violence: aggressive and rigorous policing does suppress violence.

Mr. Mullen plays no favorites. Australian, Irish, Chinese, Hispanic, and Italian immigrants, as well as black migrants from the South, are all scrutinized for their contributions to criminal violence in San Francisco. Mr. Mullen understands he will be attacked: “A book could be written on each group — and many have — extolling their various accomplishments and contributions to American society. But this is not that kind of book. This is a book about criminal violence involving minority newcomers and thus must focus on the negative contributions of a numerical minority of each group considered.”

One of San Francisco’s first criminal gangs was the Sydney Ducks, which operated in the 1850s. Criminal and Australian even became nearly synonymous, but Mr. Mullen reveals that the homicides attributed to Australians were wildly exaggerated. At the same time, though, they did commit a disproportionate number of robberies, and Robert McKenzie and “English Jim” Stuart, two of the most notorious of the Sydney Ducks, ended up at the end of a rope.

There have been many attempts to explain the high rate of robberies by Australians, including the extension of San Francisco wharves, which eliminated the need for boatmen to haul goods over the mud flats — work that was dominated by those from Down Under. The most important factor, says Mr. Mullen, is not unemployment or any of the many other reasons proffered, but a simple statistic: nearly 20 percent of all Australian men who arrived in San Francisco already had criminal records. They had been criminals in Britain and Australia, and now they were criminals in America. Although they were only six percent of early San Francisco’s population, they committed 50 percent of the robberies. “While the Australia from which the Gold Rush immigrants came might not have been particularly plagued with criminal violence,” concludes Mr. Mullen, “many of the Australians who answered the call to gold from California definitely brought criminal propensities with them.”

Contributing disproportionately to criminal homicide in Gold Rush San Francisco were Hispanics. Many were recent immigrants to America, giving the lie to the old argument that they were a conquered and oppressed people fighting the new and hated Anglo establishment. Says Mr. Mullen: “We are willing to accept criminal violence committed by Anglos in the old West — like that found in boomtown San Francisco or the wild mining camps like Bodie — as caused by some individual character flaw or because of some general societal condition — not enough law, alcohol, youth, and prevalence of firearms. Yet when ‘people of color’ are involved, we immediately start looking for some oppressive condition imposed on them by the majority to explain their criminal behavior.” Many of the Hispanic criminals were recent arrivals from either Mexico or Chile. The Chileans, says Old West historian Jay Monaghan, included rotos, whom he describes as “landless vagabonds who worked occasionally and robbed often, proving themselves dangerous highwaymen or excellent guerillas. . . . Reckless, vindictive fighters, these ragged gangsters cared little for their own lives and not at all for the lives of others.”

Many Mexican immigrants could be similarly described. Nonetheless, the myth of the peaceful old Californio turned avenger for his oppressed people persists as demonstrated by the legend of Joaquin Murrieta. Most of what California students are told today about Murrieta comes from a wildly fictional tale created by John Rollin Ridge, a part-Cherokee who published a book about the bandido in 1854. Ridge said Americans drove Murrieta from his claim, flogged him and raped his wife, and hanged his brother. Murrieta, according to Ridge’s tale, then set out on a course of revenge, killing all the gringos responsible. Actually, Murrieta was not a Californio but a Mexican from Sonora who did not arrive in California until 1849. He was not flogged, his wife was not raped, and his brother was not hanged. Murrieta led a gang that robbed and killed without compunction, attacking Americans, Mexicans, and Chinese. Murrieta and his bandidos killed nearly as many Chinese as whites, and Chinese were outnumbered by whites ten-to-one. One of Murrieta’s victims was black. Truth be told, criminal gangs like Murrieta’s were very much in operation in Sonora at this time — without any Anglo oppressors. Murrieta brought his criminality with him from Mexico.

Another popular notion concerns unequal punishment. In San Francisco, says Mr. Mullen, “from 1850 through 1859, 15.6 percent of those punished for homicide by hanging or imprisonment were Hispanic (five of 32) against their approximately six percent of the population.” It would seem that Latinos were suffering under the Anglo justice system until one learns that they committed 15.1 percent of the homicides during the same period — a near perfect match. Moreover, most of the Hispanic killings described by Mr. Mullen were Hispanic on Hispanic.

Mr. Mullen traces the Irish propensity for violence to classical antiquity. Posidonius, a Greek historian of the first century said, “These Celtic warriors were wont to be moved by chance remarks . . . to the point of fighting.” Dozens of other such descriptions are recorded. “We have no word for the man who is excessively fearless,” said Aristotle, “perhaps one may call such a man mad or bereft of feeling, who fears nothing, neither earthquakes nor waves, as they say of the Celts.” “The whole race,” noted Strabo, “is madly fond of war, high-spirited and quick to battle. . . . For at any time or place and on whatever pretext you stir them up, you will have them ready to face danger, even if they have nothing on their side but their own strength and courage.” This was 2,000 years before the Irish immigrated to America and faced prejudice. The Irish simply have a propensity for fighting. Sean McCann in The Fighting Irish describes an Irishman as “Quick-tempered and yet still a brooder on hidden angers, has never been short of a fight, right or wrong, through any stage of history.”

Mr. Mullen argues that Irishmen brought all this to San Francisco and that the propensity for fighting continued into subsequent generations. It’s in the blood. Not by accident, many of San Francisco’s cops and police chiefs were Irish, led by the city’s first chief, Malachi Fallon. In conversations with Mr. Mullen he told me that the toughest kids in San Francisco before and after his time on the force were Irish. He remembers in the late 1940s and early 1950s the older guys he grew up with would leave their Irish neighborhoods and head for the Fillmore district looking for blacks to fight.

This love of a good fight continued during the 1980s and 90s with the sons of Irishmen who immigrated to San Francisco during the 1950s and early 60s. While many white kids had been sissified or drug addled during the late 1960s and 1970s, the sons of Irish immigrants were like the kids Mr. Mullen was reared with in the 1930s and 40s. They took no guff, especially not from blacks, and were more afraid of their own fathers than of cops or anybody else. Whites found in the Fillmore district during the 1970s, Mr. Mullen told me, were usually there to buy drugs. But by the 1980s and 90s the generation of Irish sons of immigrants had come of age and, like the toughs of a couple of generations earlier, were there to fight. That they and their pale-blue eyes were strikingly out of place did not go unnoticed by the SFPD. “What might you be doing in this neighborhood,” coppers would ask. The Irish kids would answer quite openly that they were looking for some blacks who had jumped a friend. The fact that they were in a neighborhood where they were greatly outnumbered seemed not to faze them. On the other hand, blacks avoided the Irish immigrant neighborhoods in the Sunset district.

Mr. Mullen said that Irish parents reacted very differently from others to reports that their sons had been fighting. Most were astounded to hear their boys were in jail just for fighting. “The lad was fighting, you say, and you’ve put him in jail for that? Bejaysus!”

Chinese violence was usually over women or involved secret societies and their competition for control of Chinatown’s gambling, prostitution, and opium dens. While the pugnacious Irish were fighting, the Chinese were killing, often with knives or meat cleavers — and women suffered disproportionately. The Chinese were effective killers, accounting for some 20 percent of San Francisco’s homicides from 1850 through 1969, while comprising only about six percent of the population. “Model” immigrants they were not.

Unlike whites, especially in the early years, the Chinese killings were not the result of a bad night of drinking in the saloon. Disputes often came from old animosities in China over political factions or Triad associations. At the same time, the Triads controlled prostitution, and Chinese women were in short supply. During the 1870s when the white sex ratio had equalized, Chinese men still outnumbered women 20-to-one. Typical was Ah Kow’s killing of Moon Ping. The murder, said the Alta California, the state’s leading newspaper at the time, “arose out of the late difficulties about imported Chinese women.” The fashionable claim is that American immigration policies caused the sex imbalance, but Mr. Mullen explains that a prohibition against emigration of women was deeply rooted in Chinese custom and law. A Chinese publication noted that it was “contrary to the custom and against the inclination of virtuous Chinese women to go so far from home . . .”

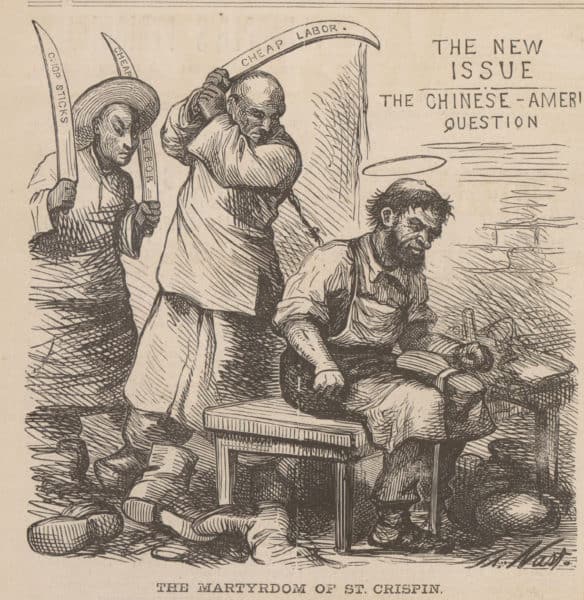

Martyrdom of St. Crispin by Thomas Nast. Harper’s Weekly 16 July, 1870. Source: UDel / Walfred

In China, protection money was the lifeblood of secret societies, and it was no different in San Francisco. Disputes that led to murder were often attributed to extortion. Tong wars most commonly resulted from battles over protection money for brothels, opium dens, and gambling halls. The first tong war in San Francisco erupted when the Suey Sing and Kwong Duck tongs had a dispute over a prostitute known only as the Golden Peach. There were Triad Society and tongs centuries before Chinese immigration to the United States, and these groups had nothing to do with the host nation.

Chinese convicted of murder were more likely than others to get the death sentence. At first glance this would seem a racial injustice. Mr. Mullen reveals that the disparity is accounted for by the murder being coupled with another crime, which usually brings a harsher penalty. Chinese criminal homicides were often a result of robberies or extortion attempts. “From a reading of the cases,” says Mr. Mullen, “Chinese homicides were almost never committed in the heat of passion, unlike those of the non-Chinese with whom the rates of severe punishment are compared.” Moreover, many of the Chinese sentenced to death had prior convictions, including convictions for murder.

Far from being marginalized by the host society, argues Mr. Mullen, the Chinese in the 19th century chose to run their own affairs by their own standards. They did not let the police and courts address their problems. Most of their conflict was internal and a good portion of it can be attributed to a decades-long battle between the See Yup and Sam Yup tongs, which helped keep the Chinese homicide rate high until the 1920s. With conditions changing in China — Sun Yat Sen had finally defeated the hated Manchus and established the Republic of China — conditions changed in San Francisco. No longer were large numbers of Chinese tong thugs arriving in California.

At the same time, San Francisco Chief of Police Daniel O’Brien decided Chinatown had to be reined in. He appointed Sgt. Jack Manion to lead the department’s Chinatown Squad and ordered him to do whatever it took to stop the killings. Manion specialized in profiling. Chinese who had the characteristics of tong killers and no visible means of support were constantly harassed and arrested. Many were deported. He also held a meeting with all the wealthy and powerful leaders of the tongs and told them that if they did not cap the killings he would have them deported. Manion had a no nonsense reputation and it brought results.

Italians had twice the homicide rate of non-Italian whites in the early decades of the twentieth century. Again, Mr. Mullen sees these rates as a product of the immigrants themselves rather than of treatment by the host society. Before 1890, Italians only trickled into San Francisco; by that year the Italian community numbered little more than 8,000. During the next several decades, however, the numbers increased dramatically until there were 57,000 Italians by 1930. Like the Chinese, says Mr. Mullen, the Italians generally came into the city as young, single, males and, like the tong gangsters, Italian Mafia or Black Hand gangsters came to extort and kill. Italians, especially southern Italians, came from a violent, vendetta-dominated society. “The propensity for violence of the southern Italians was not a symptom of social disorganization caused by emigration,” says Rudolph Vecoli in The Aliens, “but a characteristic of their Old World culture.”

Italian-Americans in the early 1900s. (Credit Image: Lewis Wickes Hine via Wikimedia)

Nonetheless, the Italian crime rates never reached the levels recorded for Italians in Eastern cities. The Italian neighborhoods, such as North Beach, were more easily policed in San Francisco and there was a greater willingness by San Francisco Italians to cooperate with the authorities. The gangsters simply did not have the cover they had in Eastern cities. Moreover, gang warfare over bootlegging did not come to San Francisco during the 1920s as it did to Chicago and other Midwestern and Eastern cities. Immigration reform contributed to reducing Italian violence as well. With drastic cuts in the number of Italians admitted to the US by new laws in 1924 and 1927, the source of fresh killers was blocked. By the 1950s Italian crime rates in San Francisco were beginning to resemble those of other whites.

Lou Calabro, who retired as a lieutenant from the SFPD and worked under Kevin Mullen, was relieved when he came on the force in the early 1960s to find his fellow Italians were close to the white norm. Mr. Calabro, with an inquisitive mind and attention to detail, studied the arrest log books that listed the name, charge, and nativity of everyone arrested and carefully noted all Italians. Even after his retirement from the force he, like his friend Mr. Mullen, continues to study crime in San Francisco and remains one of the experts in the field today.

The black community in San Francisco was also the product of immigration, not from overseas but from the Deep South. Moreover, meaningful statistical data for blacks cannot be developed until the 1940s. Before then there were so few blacks in San Francisco — less than one percent of the population — that extrapolations can lead to wildly erroneous conclusions. Mr. Mullen notes the first murder by a black in San Francisco was committed by Obadiah Paylin in 1853. He was treated rather leniently, sentenced to two years in San Quentin. His victim seems to have been black, although details of the crime are lacking. Interracial killings were soon occurring, though. During the 19th century in San Francisco, there were seven cases in which blacks killed whites and five cases in which whites killed blacks.

Blacks certainly were not treated harshly by the justice system. Case after case described by Mr. Mullen reveals surprisingly lenient treatment, even when the victim was white. A black named Lloyd Bell had some kind of dispute with John Ryan, an Irish bartender at the Drumm Street boarding house for seamen. One night in October 1873, Bell crept into the boarding house and, finding a man asleep, swung an ax into the man’s neck, nearly severing the head. As it turned out, the man was not Ryan but a customer sleeping off a drunk. Bell got seven years in San Quentin, but on appeal his sentence was reduced to one year. He was out of prison only for a couple of years before he murdered again, this time his landlady in a dispute over rent. Again, he was sentenced to San Quentin.

Members of the LAPD Gang Enforcement arrive on the scene of a double shooting from assault rifles. (Credit Image: Mark Allen Johnson / ZUMAPRESS.com)

Black murders in San Francisco increased dramatically during the early 20th century. Mr. Mullen suggests that much of this was the result of a culture of violence moving north with blacks from the Deep South. The host society does not seem to have been responsible. From 1900 through 1943 there were only two blacks killed by whites. During the same time blacks killed eight whites (and many more blacks).

The black population of San Francisco began growing dramatically during the last two years of the Second World War and had doubled by 1950. It doubled again and again until, by 1970, there were nearly 100,000 blacks in the city, comprising almost 15 percent of the population. Black criminal homicide, wildly disproportionate to population numbers, made San Francisco’s murder rate soar. By the 1960s, black murder victims were often white. By the end of the decade it was more common for a white to be killed by a black than by another white. Things got worse for whites in the 1970s. Part of this was a consequence of the infamous Zebra murders, perpetrated by blacks from a religious cult who were intent on destroying the white race. During the 1970s, 80s, and 90s the black homicide rate ebbed and flowed but always remained at least double the black proportion in the population and often triple or quadruple.

The SFPD has tried a number of different tactics to suppress black homicide but all have been discontinued after protests. The most effective tactic harkened back to earlier times when police were given greater latitude in dealing with gangsters. A unit called CRUSH (Crime Response Unit to Stop Homicide) was organized in 1995 and, over the next two years, made 700 felony arrests and seized more than 200 weapons. While murders dropped precipitously in Hunters Point and other black neighborhoods, complaints against the unit began to accumulate. “This was the cowboy unit of the Police Department,” said public defender Jeff Brown. Public defender Shelia O’Gara said that “it appeared to us that they were transferring the most volatile cops to the unit.” In May 1997 the unit was quietly disbanded. In his apartment in the Sunset district Dirty Harry Callahan consoled himself with another Jameson.

Black crime seems almost intractable. San Francisco was about as welcoming as any host society could be, but instead of the violence lessening with each succeeding generation, as it had with other groups, it got worse. Whenever the cops cracked down — a theme that runs throughout Mr. Mullen’s chapter on blacks — crime receded. Whenever the cops backed off, it surged. One cannot help but think of New Orleans and the orgy of looting that occurred as a consequence of passive or absent (or sometimes participating) police.