Could Mexico Become Somalia?

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, October 9, 2015

Cameron Holmes, Organized Crime in Mexico: Assessing the Threat to North American Economies, Potomac Books, 2014, 200 pp., $24.95.

“When the history is written of the decade from 2006 to 2016 it will be recognized as the period during which the United States condemned its northern Mexican neighbors to a failed state and the Mexican economy to ruin.” So concludes Cameron Holmes, author of Organized Crime in Mexico. He believes that the Mexican drug combines have become so powerful they could push northern Mexico into complete lawlessness and destroy its economy. Holmes points out that Mexico is our third largest trade partner after Canada and China, and that if Mexico slides into chaos it will “threaten the economic well-being of North America.”

Cameron Holmes, who died in 2013, knew what he was talking about. He first worked as a ghetto policeman, then went to law school and spent the rest of his career as a prosecutor in Phoenix, Arizona’s, organized crime unit. After years of fighting Mexican crime syndicates, he came to believe that they are such a threat to our southern neighbor that, if only out of self-interest, we must do everything we can to shore up the Mexican authorities against destruction.

Not cartels

Holmes punctures several myths about Mexican crime networks. First, they are not “drug cartels.” A cartel is a group of producers who collude to set prices, whereas the Mexican syndicates are in brutally murderous competition. Holmes calls them CEs–“criminal enterprises”–which is the term used in American RICO statutes. Nor do they depend on drug income. Indeed, they threaten the state because their nature has changed:

Their power has increased for a number of reasons, including vertical integration of distribution networks in the United States, diversification into multi-crime enterprises, militarization of tactics and operations, the availability of mercenary gunmen, the availability of high-powered weapons, and international expansion. Corruption, the CEs’ diverse sources of criminal income, their intimidation through violence, and their active intelligence gathering have symbiotic effects. Together they create and maintain a web of power that is difficult to control, because each aspect makes addressing each of the others more difficult.

Holmes argues that it was diversification out of drug- and people-smuggling that made the CEs a direct threat to the state. When the only business was smuggling, criminals had a simple agreement with the authorities: We bribe you to look the other way. Mexicans thought getting drugs and people into the United States was a victimless crime. They like getting the remittances illegal immigrants send home, and they don’t care if Americans poison themselves taking Mexican drugs.

What finally drove the Mexican government to send the army against the CEs were crimes against Mexicans: kidnapping, mass extortion, truck hijacking, and even diversion of petroleum shipments–all combined with massive corruption of police and the judicial system. These are intolerable threats to any government. But once the authorities began to take action, the CEs made it clear they were beyond the reach of government.

That is the purpose of the horrible brutality we hear about so often: beheadings, video-taped chain-saw killings, bodies hung from bridges, heads pitched into night clubs like bowling balls. In 2011, one gang dumped 35 mutilated bodies, including 12 women, at a major underpass in the city of Veracruz–in rush hour, in broad daylight. Holmes says this sort of thing sends two messages: “[We] will show horrible cruelty to any who stand in their way,” and “government is powerless to do anything about it.”

Holmes adds that the most obvious and direct threat to the state is the increasingly common practice of “choosing local candidates by assassination.” This, along with the murder of police chiefs, creates zones of virtual impunity for CE operation, and killing journalists ensures a blackout on their activities. In 2010, for example, the daily in Juarez formally announced that it would no longer run any stories the CEs didn’t like.

The result is gang rule. CEs shake down civilians and legitimate businesses for regular protection payments known as “street taxes.” No one is spared. In Juarez, criminals burned down a kindergarten because the teachers weren’t paying enough protection money. “Street taxes” squeeze people to the point they can no longer pay legitimate taxes, which means government has less money for fighting crime.

Naturally, crime flourishes. There are an estimated 40,000 kidnappings and tens of thousands of truck hijackings in Mexico every year. Armed men also drive huge trucks up to grain elevators and spend the day stealing everything. They can take their time because they know the police won’t stop them. The police themselves practice their own extortion rackets, so people no longer even report crime.

Eventually, it becomes rational for citizens to turn to the CEs rather than to the authorities for “justice.” Holmes quotes a study according to which an astonishing 23 percent of middle-class Mexicans asked CEs to help them sort out disagreements; in regions where the CEs were most powerful, the figure was 40 percent. Crime syndicates become de facto governments.

Violence

The willingness to use mass violence against the state–and against each other–is the hallmark of the modern Mexican CE. Violence is cheap because thousands of young Mexicans are eager to work as full-time kidnappers, extortionists, and assassins. Many are cocaine users who think they are invincible and who need money to support their habit. At $500 to $650 a month, their pay is much better than that of a soldier or policeman, so any corrupt policeman who is fired or let out of jail has an obvious second career. Holmes writes that a glut of gunmen has brought the price of a contract killing down from several thousand dollars to under a hundred. He points out that Mexico now has a generation of totally brutalized young men who can probably never be properly socialized.

Private armies mean new options for CEs:

With so many inexpensive young strangers available as gunmen, CE leaders are not as constrained as they had been about violent confrontations with rival gangs or with government authorities. When conflict meant that a king-pin’s own brothers, uncles, sons, nephews, cousins, and in-laws might die or be injured, naked aggression was not as attractive as a negotiated resolution or some other alternative.

The result: “Attacks that did not make strategic sense five years ago are much more attractive.” Also, high murder rates make it easy to camouflage an ordinary killing. If you want someone’s girlfriend you can get rid of him by chopping him in pieces and leaving him by the roadside. Everyone will think it was a drug-war killing.

In Mexico it is legal for private citizens to own guns, but ownership is carefully regulated. Illegal ownership is increasingly common. One survey found that in high-violence areas half of poor Mexicans owned a firearm.

The organization of crime

Mexican CEs all operate on the same general pattern. At the center is a leader who has established himself because of several qualities: a reputation for violence, a knack for criminal organizing, and a broad set of corruptible contacts in government and business. He must have a small group of insiders who are completely loyal to him, and he ensures loyalty two ways: By making sure they make a lot of money, and by torturing and mutilating waverers. The network is full of psychopaths who must be exterminated at the first sign of insubordination.

Anyone who knows enough about the inner workings of the CE to be useful is bound to the CE for life. His knowledge must stay within the syndicate. If he tries to leave, he will be killed and his family will be killed.

The different crime operations of the CE are grouped into “cells” that are isolated from each other as much as possible. The people running prostitutes don’t even know the kidnappers or hijackers.

Holmes notes that the large population of Mexican immigrants makes it easy for CEs to operate in the US. One of the most profitable changes that resulted from extending operations across the border has been vertical integration of drug distribution. Most of the profits in drug dealing are made close to street level. Holmes calculates the profits in the Colombian cocaine trade as follows: Andean growers: 1.5 percent; Colombian and Mexican transporters: 13 percent; Mexican and American wholesalers: 15 percent; Mexican and mid-level to final retailers: 70 percent. The CEs have gained billions in extra profits by controlling the trade right down to the barrio.

At the same time, Mexican-American street criminals are a useful minor league for CE recruitment. Many are American citizens, which makes it easy for them to cross the border or infiltrate American customs and police.

CEs use the Internet to sell genuine but bootlegged opioid pain killers to Americans. Once users are hooked they switch to CE-provided heroine, which is cheaper than legal drugs. The CEs are also expanding their drug trade around the world: Central and South America, China and Australia, and Europe.

Since the United States is the biggest drug market in the world, the CEs have had to figure out how to get their profits back to Mexico. Suitcases full of dollars are still smuggled across the border, but they are subject to confiscation at customs, and the smuggler might decide to disappear, along with the suitcase.

The latest trick, according to Holmes, is called “trade-based money laundering,” and it involves actual trade in Chinese goods. The US-based trader for the CE sends $400,000 in drug profits to China as a down payment on goods that wholesale for $500,000. The Chinese ship the goods to Mexico, and invoice the CE’s Mexican front company for the remaining $100,000. This means the CE now owns $500,000 worth of goods, for which the Mexican branch paid only $100,000. This means $400,000 has been cleverly laundered into Mexico from the United States via China.

The most common–and profitable–Chinese products used for money laundering are counterfeit software, drugs, videos, Gucci handbags, etc. The Chinese make 80 percent of the world’s fake goods and don’t care who their customers are. The stuff sells for a very high markup, which adds to CE profits and cuts into legitimate businesses. Holmes reports that the Zetas and La Familia have gone into the fake-goods business in such a big way that they put their own logos on products, and do not permit the sale of competing goods.

Another way to send drug profits back to Mexico is to over-invoice products exported to the United States. A $200,000 shipment of electronics from a Mexican assembly plant to the US is invoiced at $500,000. The extra $300,000 is repatriated drug profits.

Obviously, this kind of fiddle requires connections with semi-legitimate and even legitimate manufacturers, freight forwarders, insurers, etc. It may also require paying customs agents not to examine shipments with suspiciously high or low invoices. Mr. Holmes notes that as the CEs get acquainted with executives in legitimate companies, they learn whose families can pay the highest ransoms, and pass this information along to the kidnapping unit.

All aspects of CE power reinforce each other. Wealth from drugs and hijacking brings in enough money to corrupt the police. When the police look the other way, CEs can run city-side extortion rackets, and kill politicians and journalists who do not toe the line. Unchecked power–except when CEs compete for the same business–means yet more diversification into yet more criminal enterprises.

The result, as Holmes explains, is that honest citizens “are surrounded and immobilized by the illicit power web.” Instead of being suspicious when neighbors have unexplained wealth and reporting them to the police, Mexicans see such people as powerful potential allies. Ambitious parents want their daughters to marry crime bosses.

Once local governments are discredited they may never regain authority. Holmes believes that, at least in the northern states of Mexico, CEs could “strangle legitimate US-Mexico commerce” and establish vast areas of warlord rule, from which they could extend their influence ever deeper into the United States. He writes that American political leaders are “studiously ignoring the coming crisis in Mexico” for fear of offending Mexicans on both sides of the border.

Fighting back

Some outsiders think the CEs realize they could eventually destroy the Mexican economy and will be careful not to kill the host. Holmes says no. A CE always wants more revenue. The boss can satisfy the inner circle only by making more money for them, and they might strike out on their own or even depose him if he turned his back on potential profits. In any case, if one CE shows restraint, another will simply move in and scoop up the profits. If a CE could divert all of Mexico’s oil revenue it would–even though oil pays for 40 percent of the national budget and stealing it would wreck the economy.

CEs and corruption have scared away tourists–and revenue–from even the most famous resorts. The Wikitravel tourism site that is supposed to promote travel warns:

[D]rug-related violence has been increasing in Acapulco. Although this violence is not targeted at foreign residents or tourists, U.S. citizens in these areas should be vigilant in their personal safety. For the average tourist, the most frequent danger comes from local police. Bribery and extortion is at every corner.

Many people think that a quick way to defeat the CEs is to legalize drugs. Again, Holmes says no. Imagine an American company trying to get into the newly legalized cocaine market. It would have to buy its coca leaves from Andean producers, all of whom are controlled by CEs. It would have to use FDA-inspected plants, pay its workers health benefits, insure against overdose-related lawsuits, advertise, and pay excise taxes. It would be impossible for a legal provider to compete with CEs that don’t have to worry about any of that.

“No legal product can come within a multiple of ten of matching the real-world price of smuggled hard drugs,” Holmes writes. Even if a legal supplier miraculously managed to be competitive, addicts would rob and steal to support a legal habit just as they do to support an illegal one. Legalization would probably increase the numbers of users, so there would be even more street crime.

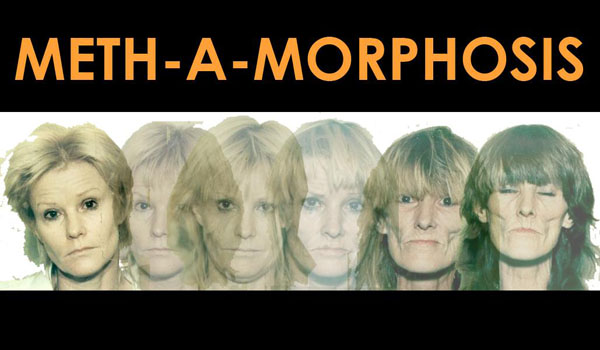

Some drugs, Holmes writes, are too horrible to legalize: “The doctrinaire position on universal legalization will always be confronted with sales of substances that are so horrible that no civil society could stand by while its members make money by selling these substances to other human beings.” He says methamphetamines cause such terrible damage to the body that they will never be legalized, thus leaving the field to the CEs.

Marijuana is a somewhat different story: It can be grown anywhere, is less destructive, and is so cheap you don’t have to be a criminal to support a habit. But here, too, the regulatory and other costs of legal production combined with high excise taxes would probably price legal suppliers out of the market. Even if they managed to get a piece of the high-end trade, legalization would probably expand the market so much that CE profits would grow.

Some users would grow their own, but Holmes points out that even though it’s easy and legal to grow your own tomatoes, hardly anyone does. Instead, they buy inexpensive, mass produced tomatoes that are available year ’round. Finally, underage users would probably be barred from buying legal marijuana, so the CEs would have that important market to themselves. In any case, marijuana accounts for only about 16 percent of the American illegal-drug market, so even if CEs were completely shut out of it, it would only dent their income.

Holmes writes that if it were possible actually to seal the border, that would cut CE profits significantly but not eliminate them. Mexicans grow a lot of marijuana in American national parks, and could move meth production north. There was a time when snuffing out US-bound smuggling might have throttled the CEs, but that wouldn’t work today. They have diversified into Mexico-based crime, and sell drugs all over the world. Whatever one thinks of legalization, Holmes reminds us that the Mafia had no trouble surviving the end of Prohibition.

So, how to fight the CEs? Holmes first points out that this is not a “war on drugs” that can be won by seizing more contraband. He sees it as a multi-faceted, international effort to keep a major economy from falling into the hands of pirates. Mexico needs better laws against organized crime, modeled on American RICO, wiretapping, and asset-forfeiture laws. It needs a better judicial system with better judges, but in the meantime it should simply send more criminals to the US for prosecution and prison. (Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman’s escape from a high-security Mexican prison in July underscores the weakness of the entire system. The Americans had offered to jail him, but the Mexicans insisted they could handle him.)

But Mexico doesn’t have the capacity to act alone. Holmes urges a “close partnership with the Mexican government,” though the UN might supervise joint US-Mexican raids so as to ease Mexican sensitivities about US “intervention.” He wants clear goals and a commitment of billions of dollars to achieve them.

Holmes points out that in any network, if you immobilize one essential part, the rest will stop functioning. Arresting street dealers is a never ending struggle because they are easily replaced. But if it were possible, for example, to keep the precursor chemicals for meth out of CE hands, the illicit trade would stop, even if manufacturing, smuggling, distribution, and money laundering were all running perfectly.

Holmes, who was an expert on financial crime, writes that the CEs’ weakest point is money transfer. He says the authorities catch an estimated 20 to 40 percent of the illegal drugs that cross borders but stop only about 0.2 percent of the payments. Mexico does not have good laws against illicit money transfer, and does not realize this could be a choke point.

He also notes that the people who handle such things as trade-based money laundering–shippers, insurers, brokers–are good targets for police action. First, they have special skills and cannot be easily replaced if they are jailed. Second, they are white-collar people with families. This means that if they are arrested, they are desperate to cooperate with the police if that means a shorter sentence. Third, they make credible witnesses at trial, unlike snarling, brutish people who sell drugs and kill people.

Holmes argues that a coordinated attack on money transfers would strangle the CEs. He writes that many have few cash reserves, and that if armies of killers suddenly stopped getting paid, they could turn on their bosses. A campaign like this would have to target all the CEs at the same time; otherwise, the strong would simply wipe out the weak.

It is hard for a non-expert to know if CEs could be put down that way, but another of Holmes’s ideas probably would not work. He thinks people could be made to understand that “Americans who choose involvement with Mexico-sourced illegal drugs are, quite simply, choosing to contribute to economic devastation for North America.” And he thinks drug users could be persuaded to care.

Holmes thinks Americans of drug-taking age are greenies who worry about carbon footprint, genetically modified crops, and “blood diamonds.” He thinks a graphically illustrated campaign with the slogan, “You get high, people die,” would shock users into at least switching to home-grown marijuana. A campaign like that would not work on blacks, or on degenerate white meth users, but college students might pay attention.

What future for Mexico?

Holmes’s predictions are sobering–but are they accurate? Could we really end up with a Mestizo Somalia? Holmes says Mexican politicians won’t admit the truth because it only underscores their incompetence, and American politicians are terrified of offending Mexicans. If Mexico blew up, Central America and Colombia would follow.

Even if there is a good chance of collapse, Congress won’t send billions of dollars south of the border. Americans already think Mexico is a huge financial drain, and most would probably want to build a nice wall and shut the place out. That would have consequences. Two-way trade with Mexico runs to about $500 billion a year, and American companies have further billions in Mexican assets. For strictly defensive reasons, if Mexico really is on the verge of collapse, and an expensive campaign against the CEs would prevent that, it’s probably a sensible economic bargain. If Mexico did become Somalia, boatloads of Mexicans would come swarming ashore just as Africans are in Europe.

Whatever happens, it is clear that Mexico has huge problems, and that immigrants–legal and illegal–bring Mexico’s problems here. The more Mexicans we send home and the fewer we let in the better.