How the Turks Handle ‘Diversity’

George Rojas, American Thinker, November 14, 2019

Credit Image: CIA World Factbook / Wikimedia

The stateless nation of Kurdistan doesn’t have a lot to offer the United States, it’s true. But President Recip Tayyip Erdoğan’s ingenious bit of population engineering should offer this stark lesson to America’s open-borders ‘woke’ class: the fallout from ethnic diversity, no matter where in the world, is always pulverizing, intractable, and inevitable.

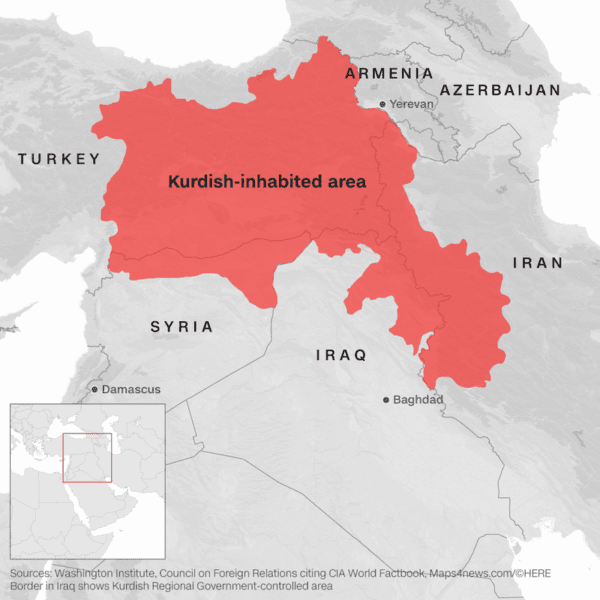

On October 5th, when Erdoğan announced his launch of Operation Peace Spring in northeast Syria, he stated that the plan sought to “neutralize terror threats against Turkey” and “prevent the creation of a terror corridor across our southern border, and to bring peace to the area.” He was out to neutralize the Syrian branch of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK): a terrorist group in Turkey, say authorities, and one that’s killed tens of thousands there in its multi-decades-long struggle to establish a greater Kurdistan ethno-state — 12 of the Middle East’s 30 million ethnic Kurds currently live in Turkey. Just like the Greek and Armenian minorities in Turkey in the early 19th century (before they were expelled and genocided, respectively), the Kurds are viewed as a constant source of distrust by the Turkish government and few forms of their ethnic expression are tolerated.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Credit Image: © Turkish Presidency Press Service/ Depo Photos via ZUMA Wire)

The October 9th military operations aimed at clearing out the Kurds from northeast Syria have since settled into a truce and Turkish troops now control a 75-mile strip of territory in the region with another section previously controlled by Syrian Kurds now being patrolled by Turkish and Russian soldiers together.

Operation Peace Spring also entails returning some of the 3.5 million Syrian occupants who have been bottled up in Turkey since 2015 when Erdoğan cut a deal with Angela Merkel and the EU to halt migrants travelling through the country en route to richer places like Germany, Sweden, and Italy. The Turkish government has announced plans to spend nearly $30 billion on Syrian resettlement efforts in the region, including the building of homes and agricultural infrastructure. Currently, Syrian migrants in Turkey live mostly in tent and container cities. One hundred thousand have been returned to the region so far.

This resettlement part of Erdoğan’s plan has been wildly popular among the Turkish people. From the outset of the Syrian influx, Turks have complained about strains on local labor markets, public services, and housing capacity. Due to these, as well as cultural problems, polls show nearly three-quarters of Turks want a return to the pre-influx status quo. And largely because of this promise to return, a massive 85 percent of the Turkish population is supportive of Erdoğan’s plan.

Yet another motivation behind Operation Peace Spring, says Turkish affairs expert Ryan Gingeras in the New York Times, is that a return of Syrians into Kurdish-held Syria would create “a living, breathing demographic barrier to Kurdish autonomy.” This motivation, which the International Crisis Group’s Dareen Khalifa has also noted, would further dent Kurdish aspirations in northeast Syria by diluting their numbers and creating ethnic factions in the region.

In sum, Erdoğan’s three-pronged plan is essentially about softening inter-ethnic tension in his own country (i.e. removing Syrian occupants, dulling the Kurdish autonomy movement), while creating it where it would benefit his own power base (i.e. building up tensions in northeast Syria). Each are facets of the same age-old, cross-cultural problem of how to deal with interethnic conflict. But, while no doubt extreme, Erdoğan’s plan is not at all without precedent. Nor, on a fundamental level, is it completely far-flung from America’s own efforts in maintaining multicultural stability; efforts which, by the way, will likely increase in the future. Probably dramatically so.

Turkish soldiers on the Syrian border.

Conflict between ethnic groups, of course, is as old as the dirt they fight over. From the ancient story of Arminius, a German citizen of Rome who led his fellow tribesmen against the Roman army, to the ethnic breakup of the Russian, Hapsburg, and, of course, Ottoman empires, to today’s paralyzing distrust between Afghanistan’s Pashtun, Hazara, Tajiks and Uzbeks; concern over dual loyalties and ethnic civil war appear cross-culturally and across time.

So does divorce between groups locked in shotgun marriages. Just taking examples your average boomer might have watched on TV, there’s the Singaporean Chinese leaving the Malaya federation, the Czechs splitting from the Slovaks, the breakup of the Balkans, and the partitioning of Sudan. While some were bloody and some weren’t, all were predictable and for the best. Putting it in academic terms, UC Berkley sociologist Donald Horowitz once noted, “[t]he desire to extirpate diversity seems greatest in states that are among the most heterogeneous.”

Also frightfully common is the kind of ‘demographic engineering’ Erdoğan’s engaged in. Whole books have been written about the subject, covering examples of blunt population restructuring, such as China and the Soviets’ respective funneling of Han Chinese and ethnic Russians into Tibet and Estonia; to more subtle endeavors, like the UK Labor Party’s late nineties immigration increases aimed at diluting the Tory vote. If building up ethnic tensions can somehow benefit a government’s power base, it seems, ethnic tensions will be built up.

Take the Ottoman “Millet” system (roughly meaning ethnicity or nationality) that reigned up until the founding of modern Turkey. In it, minorities in the sprawling heterogeneous state were granted a limited level of autonomy and tolerance, but with an overarching Sunni establishment always keeping a firm grip on things. As part of a divide-and-conquer strategy, the Ottomans would often settle violently opposed nationalities next to each other and allow them to work only in livelihoods that depended on their hated neighbors.

Although a passing grade in junior high history and an issue or two of Foreign Policy should suffice in making the average person cognizant of the pitfalls of ethnic diversity, there’s also the area of evolutionary biology which, although some of us refuse to agree with it, we should probably defer to for safety’s sake.

Evolutionary biologists and their forerunners have long found that our differentiation and skepticism of outgroups is an ingrained tendency that inhabits us all. Building on the work of people like J.B.S. Haldane and W.D. Hamilton, Yale’s William James McGuire concluded way back in the late 1960s that “…it appears possible for specific attitudes of hostility to be transmitted genetically in such a way that hostility is directed towards strangers of one’s own species to a greater extent than toward familiars of one’s own species or toward members of other species.” In the 1970s, Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson noted that this same transmission takes place in the animal kingdom as well. In other words, as its inherent, outgroup suspicion may have to be dealt with, not through platitudes and public service announcements, but by way of cold, hard acceptance and sober policy prescriptions.

As of late, the West in general is doing a pretty poor job at this. Take our utter lack of circumspection when it comes to our rapid move from having relatively homogenous states to quarreling heterogeneous ones. Perhaps, identity-based strife is now so commonplace in Western daily life, we’re too anaesthetized, tired, or cowed to contemplate what an acceleration of tensions could really look like. How far will conflict management in the U.S. have to go as ethnic heterogeneity barrels ahead? Thankfully, the other side’s beginning to show us.

Both the New York Times and the Washington Post recently published op-eds that, while focused solely on the extreme ends of white identity politics, essentially argued that policing tribal impulses in the U.S. and keeping a lid on intergroup provocations means we will have to narrow what’s considered acceptable public discourse and speech freedoms generally. By way of more de facto and even legal censorship, all things which spark multicultural disharmony (racial satire, “derogatory” jokes, etc.) will have to go.

Surely, this will also mean ramping up what we already do to keep the expanding non-white populace at bay i.e. revising our shared national history and heroes; multiculturalizing the workplace and social sphere; allocating jobs, school admissions, and government contracts for non-whites, etc. How far will these and other existing measures have to be increased? Will brand new, more drastic measures become necessary? Will an Erdoğanesque reorientation of things have to appear in West? We shall see.