Today’s Defeat Will Be Tomorrow’s Victory

Frank Borzellieri, American Renaissance, November 1997

Early on in 1997, in an attempt to give Eurocentrists a voice in the belly of the multicultural beast, I decided to run for a seat on the New York City Council. I risked an uphill battle against a powerful Republican incumbent because he had arranged a sweetheart deal with the Democrats to run unopposed in the general election. If I could win in the primary there would be no Democrat to fight in November.

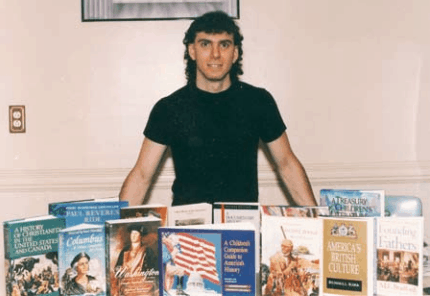

Frank Borzellieri with some of the books he advocated be used in schools.

In what turned out to be more than a symbolic gesture, my campaign authorized and paid for a solicitation from Jared Taylor to supporters of American Renaissance, asking for donations to our campaign. When the smoke finally cleared on Election Day, we had been outspent by a margin of seven to one in an election we lost by a vote of two to one. But the reverberations of our campaign will be felt for a long time to come.

We lost, all right, but not for the reasons most people would suspect. There are lessons to be drawn from every campaign, and I would like to offer my perspective on what happened and why.

The overwhelming majority of people have very little conception of how a political campaign works. Electoral politics — the specific endeavor of trying to get more votes than an opponent — is very hard-headed, brutal, exhausting business. Issues matter, but they matter only if all other things are equal. And more often than not — especially in local elections — things are not equal. What makes them unequal, of course, is financing. As the saying goes, “Money is the mother’s milk of politics.”

Many people believe that political campaigns are exciting, glamorous, Hollywood-type affairs, with teams of advisors huddled in back rooms devising strategy while the candidate is out shaking hands. This can be the case but it usually is not. In my case, as with most insurgents, the black cloud that hung over the campaign from day one was the constant need for money. Without it, you cannot run a serious campaign. I was, therefore, spending more time than I should have on the telephone asking for money or asking supporters to raise money.

Money is far more important in a local race than it is in one for President, governor, or mayor of a big city. While money is important in big races, it is not likely to be the crucial factor. First of all, in order even to reach the point of running for major office, a candidate must already have a lot of money. Also, major races get so much free media coverage that advertising is far less important.

For example, why did Bob Dole close the gap by about 12 points on President Clinton immediately following the Republican National Convention? Very simple. For four days the American people heard nothing but speeches about how great Bob Dole is. Within a few weeks, the Clinton campaign had its convention and the numbers changed again. But in a local election, where public opinion is not swayed by nightly reports on the television news, it is mainly a candidate’s ability to pay to get his message out that counts. “Issues” certainly matter, but they matter only if the voters hear about them.

Issues matter most when there is saturation coverage. That is why no one would ever claim New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and President Bill Clinton were re-elected because they outspent their opponents. They were simply perceived, rightly or wrongly, as having done a good job and as better alternatives to their opponents.

Contrary to what our detractors would love to claim, I did not lose because of the issues AR readers care about. I lost because we didn’t have the money to publicize them. In fact, my opponent saw so much merit in my views that he began sounding just like me.

Challenging an incumbent is a daunting task. The advantages of incumbency are enormous — usually insurmountable — and this is especially true in New York State. Just as with financing, incumbency is much more important on the local level than in a major, high-profile race. Campaigns for Senator or mayor of a big city are generally judged by the voters on the merits and incumbents often lose.

On the local level, incumbency is tantamount to lifetime tenure. The re-election rate for local office holders in New York State is 98 percent, a rate higher than the 90 percent rate for United States Congress. (Even in 1994, the year of the “Republican revolution,” in which a massive turnover supposedly took place, the most important advantage was not being a Republican, but an incumbent; incumbents were still re-elected at an 88 percent clip.)

There are many reasons why incumbency is so important on the local level, but the most important, again, is money. The ability to raise money, the power of the political machine that all incumbents enjoy, the reluctance of people to donate to a challenger for fear of repercussion, the free “name-recognition” that an incumbent receives — not only from the press but from “constituent” mailings paid for with tax money — all contribute to this built-in advantage.

If incumbency is an enormous advantage throughout America, in New York it is practically a coronation. It is the incumbents, of course, who write the laws, and they write them to favor themselves. Even becoming a candidate (getting your name placed on the ballot) is extremely difficult without the power of a political machine. Qualifications vary from state to state, but in New York we have what is called the “petition process,” in which supporters circulate petitions on behalf of a candidate and get the required number of signatures. The number of signatures is ridiculously high — so high that a federal judge had to step in in 1996 and order Pat Buchanan put on the ballot for the Republican Presidential Primary, stating that the qualification process violated New Yorkers’ rights to a democratic election.

For my City Council race, we needed a total of 800 signatures. Since signatures are subsequently open to “challenge” and disqualification, the rule of thumb is to try to get double the number needed, in order to withstand a challenge. In our case, we got over 1,700 signatures. Eight hundred or even 1,700 signatures may not seem like a lot, but these names usually have to be gotten house to house, and only registered Republicans can sign. It takes an inhuman amount of time and effort.

An incumbent can easily get signatures because of the power of his political machine, that is to say, the large number of people who are employees of the incumbent or are part of the official local political committee. They are always ready to work for or help an incumbent. An insurgent candidacy must devote all its time and energy to qualifying.

When our petitions were filed, they were immediately “challenged,” meaning the authenticity of the signatures was legally questioned. If a sufficient number of signatures can be shown to be invalid and “knocked off,” thereby reducing the number below the minimum, the candidate is disqualified. Signatures are invalid if they can be shown to be forgeries, duplicates, or of people not qualified to vote in the election.

New York incumbents routinely “challenge” opponents’ signatures, both at the Board of Elections and in the courts. This can be done on any pretext, merely to force the candidate to spend money on lawyers’ fees and paralyze his campaign. The law in New York does not punish frivolous legal challenges to petitions — there are no sanctions and the loser does not pay court costs — so any well-funded candidate has nothing to lose by taking his opponent’s petitions to court. But first they have to be challenged before the New York City Board of Elections, which is supposed to make an objective determination about the probable invalidity of the petitions before the case goes before a judge.

If you want to see a Kangaroo court in action, forget the old Soviet Union; just visit a hearing of the board. The Deputy Director of the board was my opponent’s wife (!) who sat on stage overseeing the group of trained seals that shamelessly violated its own rules by allowing the process to move forward to court without any justification. One independent panelist — ironically, a liberal Democrat from Manhattan — stood up in protest over this outrage, blasted the other nine members, and gave my opponent’s wife an icy stare. A more open-minded, fair decision could have been expected from the O.J. Simpson criminal trial jury.

On to court we went, where we were forced to spend thousands of dollars on attorneys’ fees. Of course, our petitions were perfect. The judge scolded my opponent’s lawyer, essentially accusing him of bringing a frivolous suit, declared my petitions valid, and ordered my name put on the ballot. But my opponent’s strategy worked. A lot of money that we had painstakingly raised could not go toward fliers, mailings, advertising or anything else for the campaign.

Not Entirely Alone

Nevertheless, the campaign began well enough. Although I was battling my opponent, his machine, the Board of Elections, the media and the entire political establishment, I was not entirely alone. Former New York State Republican candidate for governor Herbert London endorsed me, as did a former local assemblywoman. National Review said some kind words about me in an editorial, and Sam Francis wrote favorably about me in his syndicated column. But outside of that, the world was out to stop us at any cost.

In announcing my candidacy, I accused my opponent of selling out on all issues conservatives care about — official English, racial quotas, funding illegal immigrants, term limits, the right to bear arms — and declared myself the true Republican. The next night we debated on New York 1, a local cable station. The moderator, a black reporter, asked me, “Do you believe that someone who would refer to Dr. Martin Luther King as a “leftist hoodlum’ should sit on the City Council?” “Yes,” I replied, “that’s me.”

For most of the debate I slammed my opponent for ignoring crucial issues, while he bent over backwards trying to convince the audience he was a real conservative. By all accounts — even those of the adversary press — I pummeled him. After the debate, he appeared shaken. Needless to say, he did not agree to any more debates for the rest of the campaign.

Instead, he pulled out the awesome machinery that only incumbents enjoy. For the next four weeks, he continuously mailed out expensive, glossy, sophisticated mailings emphasizing official English, immigration reform and all the other issues he was stealing from me. And he could do this at taxpayers’ expense.

Under the guise of “reports to constituents,” he spent roughly $75,000 of tax money promoting his campaign. Incumbents are allowed by law to make tax-payer-financed mailings of this kind (which must not mention the challenger’s name) up until ten days before the election! And why not? It is the incumbents who write the laws. Rather than run a fair election — man vs. man on the issues, on our records, and on the merits — my opponent realized in a hurry that his only road to victory would be to outspend us by a huge margin, and bury us under an avalanche of mailings and advertisements, as all incumbents do and only incumbents can.

There was such a difference in campaign volume that my opponent could actually give the impression that he was the only candidate. Since voters were getting swamped with his mail, many probably didn’t know they could vote for me unless they read about it in the newspaper. Much as I would love to blame my defeat on the liberal media, which demonized me, I cannot honestly do so. After all, sensible people see through absurd charges of racism. The problem was money.

A perfect example of the wonderful things money can accomplish in a campaign is “voter ID and pull.” The concept is simple, effective — and very expensive. It was actually first articulated by Lincoln, who said, “Identify who your voters are and get them to the polls on election day.” Simple though this is, it cannot be done on the cheap.

“Voter ID” entails sending out “preliminary” mailings touching on the candidate and his pet issues. A phone bank is then run to contact the entire eligible enrollment to “ID” the voters most likely to vote for your candidate. You now have a prime list of “favorables” whom you can target for “get-out-the-vote” mailings at the end, as well as the crucial “pull” telephone operation in the final days. You can ignore voters identified as favorable to your opponent or you can target them with negative mailings to diminish his support. In a primary, where turnout is always low, “voter ID and pull” — the ability to identify your supporters and get them to the polls — is crucial. Needless to say, my opponent had the money to do this and we did not.

I wanted to make race, immigration and multiculturalism the issues in this campaign, not only because these were the issues on which I was well known and had used so successfully in winning elections in the past, but because the voters are hungering for someone in high office to address these issues in a realistic manner. All politicians run for the tall grass on these issues but, much to the chagrin of the establishment, I had proven that, when articulated in a no-nonsense manner, these issues are winners. With our finances badly bled by the court challenge, we were unable to get the message out. We did manage to make several mailings near the end, but a very effective piece on immigration, for example, which got a good response, we could afford to send to only one section of the district.

My campaign consisted mainly of my going house to house for months — I lost 17 pounds in the process — and my volunteers working the phones, stuffing envelopes, and attaching labels. Our campaign was run by devoted, hard-working people (including an AR subscriber who flew in from Chicago and manned the phones for a day) but it lacked the resources to compete on a fair playing field.

Surprisingly, the press treated me decently for a time. They played up my complaints about my opponent spending tax dollars on his campaign and stealing my issues. They also mentioned the scandalous court challenge to my petitions, which bankrupted the campaign. However, things returned to form when a columnist for the New York Daily News wrote about me so unfairly that even other reporters were amazed.

An affirmative-action writer named Albor Ruiz entitled his column “Just Conservative — or a Plain Bigot?” “Frank Borzellieri,” he wrote, “who wants to be a City Council member, believes that slavery was a good thing.” Of course, my point was that blacks enjoy a higher standard of living in the United States than they do anywhere else in the world, so it is a fact that the act of bringing slaves to North America benefited today’s blacks. But my opponent played the Ruiz slander to the hilt, calling me “a dangerous man, looking to hurt people.” For the remainder of the campaign, he was constantly quoted as calling me as “a skinhead with curls.”

AR Becomes an Issue

After I had had lunch with him one day, a New York Times reporter called me late that night at home to ask about something he had found on the Internet: an appeal for assistance “from someone named Jared Taylor.” AR had become an issue in the campaign. Neither Mr. Taylor nor I had any idea that his appeal had been posted on the Internet, but when I was questioned about it, I impressed upon the reporter that I was proud to have AR’s support and that the appeal was, indeed, bringing in money. The press and my opponent went crazy.

My opponent, who had never heard of Jared Taylor, started referring to him as a “neo-Nazi,” and the appeal letter was quoted at length in the local press. Mr. Taylor and I both spoke to reporters about AR, emphasizing that conferences draw mainstream figures including professors, columnists, and clergymen.

Still the rumor about “neo-Nazis” went all the way to the top. New York Governor George Pataki, who ordered the Georgia state flag removed from the capital building in Albany because it represented “racism,” reportedly said at one of my opponent’s fundraisers, “I normally do not get involved in Republican primaries, but in this case I must take a stand because one candidate is getting money from hate-mongers.” My opponent circulated a letter to a local civic group, the Ridgewood Property Owners, an organization whose members had contributed to my campaign and that consists mostly of old Germans. The letter, written by a former member of their board of directors and a supporter of my opponent, stated, “Mr. Borzellieri fancies himself an advocate for white people and has adopted the point of view of American Renaissance, a neo-Nazi organization . . . God forbid Mr. Borzellieri were to be elected, he would cast a pall of bigotry on our community, and our community would become the battleground for racial violence from fringe extremist groups . . .”

At the public meeting of the Ridgewood Property Owners, at which both candidates spoke, this juvenile letter went over like a lead balloon. Ridgewood is my home neighborhood and the members know me well. Neither my opponent nor I mentioned the letter in our remarks. The important point is, once again, that if the election were actually decided on these things, with finances being relatively equal, I would have been the clear winner. I half-jokingly asked my opponent in a private moment to please send the letter throughout the district, as it would win the election for me.

As the campaign drew to a close, the newspapers weighed in with official endorsements. The Queens Tribune, in a hysterical editorial, wrote that my opponent is “a man of compassion who believes in simple things like equality for all. His opponent is a racist, reactionary embarrassment who does not. Frank Borzellieri, who calls himself “Euro-centric’ is a white supremacist cloaked in intellectual disguise. He is the most unacceptable candidate to run in this borough in our paper’s 27-year history of covering politics. He brings to the debate the most vile and ugly of human feelings. Voters must turn out to reject the racism he espouses.” Whew!

The Queens Gazette, always more sympathetic to me, also did a major article on the AR angle, stating I had some good ideas on education but needed “more maturity” (translation: become more liberal.) The major New York papers naturally, endorsed my opponent. It was in the same, final week of the campaign that the favorable National Review editorial appeared, noting my position that illegal immigrants should be “rounded up and deported.”

During this period I spoke by phone to Mr. Taylor nearly every night. Exhausted though I was, I assured him that we must hold firm and emphasize that the majority of citizens agree with the AR point of view. A candidate must publicly stand with American Renaissance, whatever the consequences, and I was proud to do this.

Temporary Setback

Despite this temporary setback, there are several points that I must emphasize. First, I have won every election that I have run (primaries and school board) in which my opponents did not enjoy an overwhelming financial advantage. In other words, when the campaigns were decided on issues (and I have always emphasized the kinds of issues discussed in AR) I was the winner. All these elections took place in the same general geographic boundaries. In 1994, I won two primaries against an even more powerful incumbent member of the New York state legislature, when the number of votes needed was small enough that I could afford the campaign. (I lost in the general election when I was outspent 12 to one.)

In 1996, I made history by obtaining more votes, relative to my opponents, than any school board candidate in New York City history. The point I stress is that we will win when we are not outspent seven to one, as we were in this election. We won on the issues, as even my opponent’s literature proves. Thanks to our campaign, he (at least temporarily) got religion.

I also want to emphasize that if I made one mistake, it was in not making an all-out, nationwide financial appeal to our ideological kindred. Excepting AR, I appealed for funds only in the conventional method — from politicians, community people, etc. AR readers are serious and dedicated — and I am deeply grateful for their generous support. Most people are not serious or dedicated. I generally found that local people, even those who wanted me to win, are basically cowards and bootlickers. Most were afraid of contributing for fear of retaliation. Had I made a more serious appeal to Eurocentrists and middle Americans, we would have been at even strength and we would have won.

I am a strong believer in the need for our people to enter the legislative and electoral process. It is not enough to complain about our problems; we must do something about them. And we must not compromise. There are now term limits on the New York City Council, so the next election will have no incumbent. We know that we are correct in our views, no matter how politically incorrect. I know the terrain well now. Success in New York City will always have national ramifications. If we can learn the lessons of this campaign — and I know we can — the next election will be a victory.