Can the South Survive?

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, August 2004

Michael Andrew Grissom, Can the South Survive?, The Rebel Press, 2001, 705 pp.

Although the title of this book is Can the South Survive? it could have had the subtitle Can America Survive? or Can Whites Survive? This is to say that although it is a book about the South, written by a proud and loyal Southerner, the questions it asks go far beyond sectional interests. Michael Grissom’s main concern is whether there is a realistic hope for a distinctly Southern nation, but he understands that the South’s decline into irreligious, miscegenist vulgarity is part of a sickness that afflicts whites everywhere. The great strength of this book is that although it ranges widely over history and culture, it never loses sight of the central question of race. Michael Grissom is that rare and refreshing Southerner who never apologizes.

The Old South

Mr. Grissom begins with an explanation of what makes the South southern. It is good as far as it goes, but deserves more than 34 of the book’s 705 pages. Mr. Grissom has covered this ground more thoroughly elsewhere, particularly in his 1988 book, Southern by the Grace of God, but readers less familiar with the South will want a better-rounded picture of what the author so passionately defends.

Mr. Grissom starts with four distinctively Southern traditions: a feudal theory of society, a code of chivalry, a firm concept of the gentleman, and a pervasive religiousness. Southerners thought seriously about what God, honor, and breeding required of them. Men avenged insults on the field of honor and, as Mr. Grissom writes, “falsehood, like an act of cowardice, was supposed to lose one his standing in society.” He adds that “every woman was a lady; ladies were to be protected; their virtue assured; their honor unquestioned.”

The total war Sherman and Sheridan waged against the South was an incomprehensible outrage against this deep sense of propriety. Mr. Grissom quotes Confederate Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin:

If they had behaved differently; if they had come against us observing strict discipline protecting women and children, respecting private property and proclaiming as their only object the putting down of armed resistance to the Federal Government, we should have found it perhaps more difficult to prevail against them. But they could not help showing their cruelty and rapacity, they could not dissemble their true nature, which is the real cause of this war. If they had been capable of acting otherwise, they would not have been Yankees, and we should never have quarreled with them.

Once their country was invaded, Southerners defended their way of life with a single-mindedness that commanded admiration. Colonel Arthur Freemantle of the British army, who marched for a time as an observer with the Southern armies, concluded his diary with this tribute:

The more I think of all that I have seen in the Confederate States of the devotion of the whole population, the more I feel inclined to say with General [Leonidas] Polk — ‘How can you subjugate such a people as this?’ and even supposing that their extermination were a feasible plan, as some Northerners have suggested, I never can believe that in the nineteenth century the civilized world will be condemned to witness the destruction of such a gallant race.

Of course, the “gallant race” was defeated, and if it was not entirely destroyed, it’s confidence was badly shaken. Mr. Grissom explains:

The bitter taste of defeat, the ensuing horror of Reconstruction, and the collapse of his [the Southerner’s] stable social order — reinforced by the pervasive Yankee textbooks from which his children formed their ideas — convinced him that he had been wrong, or at best had taken the wrong road and was, therefore, obligated to try things the Yankee way, to see it the Yankee way.

Already by the end of the 19th century, Henry W. Grady of Atlanta had popularized the phrase “New South,” by which he meant commerce and industrialization on the Northern model. The South was to make money-making life’s chief end; it was to “outyankee the Yankee” as one Southern editor put it.

Still, the South avoided some of the restlessness of the North. Mr. Girssom quotes John Crowe Ransom, writing in 1930 about Southern communities: “Their citizens are comparatively satisfied with the life they have inherited, and are careful to look backward quite as much as they look forward.”

John Crowe Ransom (Credit Image: Robie Macauley / Wikimedia)

Of course, what increasingly made this satisfied life intolerable to the rest of the country was the subordinate position of blacks. Blacks had been in the South in large numbers since the 18th and even the 17th centuries, and whites had established hierarchical relations that persisted long after slavery. Even in 1960, there were still 140 counties in the Old Confederacy in which blacks outnumbered whites, and equality was unthinkable. William Alexander Percy’s 1941 novel, Lanterns on the Levee, reflects one thoughtful Southerner’s observations about blacks:

Murder, thieving, lying, violence — I sometimes suspect the Negro doesn’t regard these as crimes or sins, or even as regrettable circumstances. He commits them casually, with no apparent feeling of guilt. White men similarly delinquent become soiled or embittered or brutalized. Negroes are as charming after as before a crime. Committing criminal acts, they seem never to be criminals. The gentle devoted creature who is your baby’s nurse can carve her boy-friend from ear to ear at midnight and by seven a.m. will be changing the baby’s diaper while she sings ‘Hear the Lambs a-calling.’” He goes on to ask: “Is the inner life of the Negro utterly different from ours? Has he never accepted our standard of ethics?

Still, explicit commentary on racial differences was rare. Mr. Grissom quotes the “Yankee-born Carleton Putnam:”

The South, after generations of experience, had developed customs and a way of life with the Negro that took his limitations into consideration with a minimum of friction and a maximum of kindness. It was entirely against these customs, these adaptations, openly to analyze and publicize the reasons for them.

However, when outsiders began to interfere with race relations, delicacy became a disadvantage:

The truth is that responsible Southerners have deliberately weakened their own defense because of their unwillingness to raise the underlying problem. They talk of states’ rights when they should be talking anthropology, and they do so out of instinctive human kindness. There is a point at which kindness imposed upon ceases to be a virtue.

In 1951, the NAACP, which had until then considered the South impregnable, held its national convention in Atlanta. This marked a shift in emphasis and the beginning of a campaign against which the South was poorly prepared. The North proceeded to bully the South with a zeal born of ignorance, but Southerners never mounted a coherent defense.

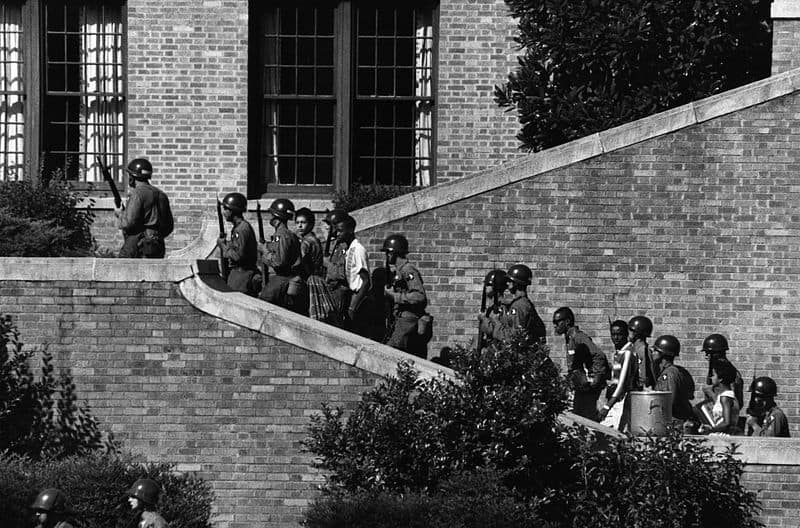

“The South,” writes Mr. Grissom, “was teeming with traveling troublemakers” who, together with the federal government, were behind the tumultuous events of the period. Mr. Grissom ably tells the stories of the integration of Little Rock Central High School in 1957, the “freedom riders” of 1961, the near-war at Ole Miss in 1962, the Birmingham church bombing of 1963, and the Selma-to-Montgomery march of 1965.

The integration of Little Rock Central High School.

Throughout this period, there was some white resistance, but little unity and bad leadership. Blacks, as Mr. Grissom points out, very quickly learned to stick together: “[B]loc voting works to the advantage of the negro in that his is the only special interest group which can be counted on to stay the course consistently, a decided advantage when it comes to extracting promises from weather-vane politicians.”

Among whites, “the moderate became the liberal’s best friend,” writes Mr. Grissom. “Always counseling moderation, inaction, passivity, the moderate never managed a stand on anything.” The South was also betrayed by its newspapers, many of which were owned by Northerners. Even those with roots still in the South had editors who played to a New York audience rather than to their own readers. Ministers, as well, were quick to capitulate, and whites became so demoralized that “the presence of a single black is enough to intimidate a whole room full of whites.”

Mr. Grissom describes some of the consequences of this loss of nerve. A visit to Central High School today finds that what was once the pride of Little Rock needs millions of dollars of repairs, sits in a blasted neighborhood — and hosts a museum that tells the integration story. “Not only do liberals do stupid things,” he writes; “they commemorate them.”

Mr. Grissom always includes the parts of the story liberal cheerleaders leave out. He notes that years after the integration of Ole Miss, James Meredith didn’t have quite the view of the event he was supposed to: “They would have been crazy not to fight against me, because I went there to fight them,” he said. “I went there to take their good thing away from them.”

Despite the long string of racial defeats for the South, the region still retains some sense of race. The common joke in the South when Lisa Marie Presley married Michael Jackson was that this was proof Elvis was dead. If “the King” had had a spark of life in him he would have showed up to stop her marrying a black man.

Final Collapse

In Mr. Grissom’s view, the “civil rights uproar” was central to a generalized collapse of decency. It pre-dated drug-taking, the “free-speech” movement, and demonstrations against the war in Vietnam, but it merged with them, made use of them, and outlasted them. “There was not an issue in the Sixties that couldn’t be connected to a black cause,” he writes.

The 1960s saw not only the overthrow of the racial order but virtually every other order as well. “We are always only one generation away from apostasy, and one untaught, untrained, undisciplined generation is all it takes to break the chain of civilization’s perpetuity,” writes Mr. Grissom. “That generation was the one the Sixties gave us.”

He calls modern culture “a sea of pollution,” and has the greatest revulsion for the coarseness that now characterizes language, dress, manners, and behavior. He blames much of the decline on television, and wishes it had never been invented: “If Southerners don’t quit watching TV, I fear it will rob us of our very souls.” Mr. Grissom frankly favors censorship, and complains that too many people will betray their principles for fear of being called “prudes.”

Mr. Grissom takes his faith seriously, and writes angrily about “imitation churches” that apologize to blacks, ordain women, promote miscegenation, fawn over homosexuals and AIDS carriers, and join in attacks on Southern symbols. He argues that efforts to “change with the times” and to be “relevant” have left churches with smaller congregations than ever. How, he asks, can anyone be attracted to an institution that calls God the “father-mother” and evokes the “mighty hand” of God rather than His “right hand” for fear of offending southpaws? “If the religious institutions of the South do not function properly,” he asks, “what can the South expect in the way of order, morality, and stability?”

These are, of course, problems that concern the whole country and not just the South. Mr. Grissom also writes about the dangers of “an immigration policy based upon trying to avert charges of racism,” and his chapter on why the Republicans cannot save the South could have been entitled why they cannot save anything. They are, he notes “simply one branch of a single-party system,” and it is because of them that the word “conservative” “has become so perverted that it resists definition” and is “a term sadly in search of a meaning.”

Is there any hope for the South? Mr. Grissom is not sure. “One must eventually ask,” he writes, “if Southerners . . . can even be moved to a consideration of their plight.” Most, he fears, have become “a people who have forgotten who they are.” In this respect, Southerners are no different from their Northern — or European — cousins. The white man, Mr. Grissom writes, “doesn’t even realize he is in a war. He fails to comprehend the seriousness of his own situation and probably won’t until he is in the minority — and then it will be too late.”

This book’s final prescription for the South is not realistic. Swallowing his deep disapproval of the man, Mr. Grissom quotes Abraham Lincoln from 1848 — “Any people anywhere, being inclined and having the power, have the right to rise up, and shake off the existing government, and form a new one that suits them better” — and proposes secession. Secession appeals to Southerners nostalgic for the gallantry and bravery of their Confederate ancestors, and who believe that if the South were somehow free of Yankee domination it would return to the healthy ways of the past.

Secession would be wonderful. There was, at one time, a Southern nation, and it could perhaps be reborn. However, separatist sentiment among whites is more likely to follow racial than sectional lines. Many Southerners will look to Northern whites for racial allies before they look to blacks for regional allies (though Mr. Grissom does not consider blacks Southerners: “Historically, the term has never been applied to the negro . . .”). Mr. Grissom understands that the central problem for the South has been race, but for secession even to get a hearing, it would have to be offered as something that would appeal to blacks. That is no different from preaching states’ rights when the problem is anthropology, and that approach failed.

Mr. Grissom understands what is at stake. Immigration and low birthrates are quickly eroding the majority, and if the white man disappears, “he will take with him his sense of fair play, his unswerving commitment to the underdog, his belief in personal responsibility, his willingness to aid those in distress, his aversion to crime, his strong sense of family, and his ability to create and maintain stable governments.” Precious as the South may be, there are a few things that are even more important.