The Great Replacement in Belgium

Guillaume Durocher, Unz, December 14, 2019

The following is a translation of an article by the lawyer Paul Tormenen for the identitarian think-tank Polémia. The numerous sources cited are detailed in the original article. This piece provides a solid overview of the tremendous demographic transformation which Belgium is undergoing and of the striking differences between European and Islamic migrants, the latter being markedly socially conservative and prone to unemployment. Entire neighborhoods such as Molenbeek have become unrecognizable and begging Gypsies have become a familiar sight on street corners.

At the same time, the numbers show that, as of today, a majority of immigrants to Belgium are of European origin and can be expected to integrate smoothly. Even if we concede that the Europeans are likely less fertile than the Muslims and Africans, this is one reason why I do not believe “race war” is likely to happen any time soon, notwithstanding the reality of Afro-Islamic criminality and periodic murderous Islamist terrorist attacks.

If Belgium experienced waves of immigration in the 20th Century, the current wave is unique in its magnitude and the fact that it is “endured” by a part of the population. The ethnocentric demands and the radicalization of a fraction of the immigrant population has provoked differing reactions among the [French-speaking] Walloons and the [Dutch-speaking] Flemish. In Belgium, as in other European countries, the migratory and identitarian questions have become central to the country’s political life.

From the 20th Century to Today

A first wave of immigration was organized during the interwar years, due to the pressure of the Belgian leaders of heavy industry. Labor migration was started up again in the 1960s. These immigrants were notably called upon to work in the mines and were essentially of European origin (Italy, Spain, Greece). After 1964, bilateral agreements were concluded with Muslim countries (Morocco, Turkey, Algeria) in order to facilitate the hosting of foreign workers. Without regard for any cultural factors, familial immigration was also promoted in order, according to Belgium’s leaders, to tackle the country’s aging population.

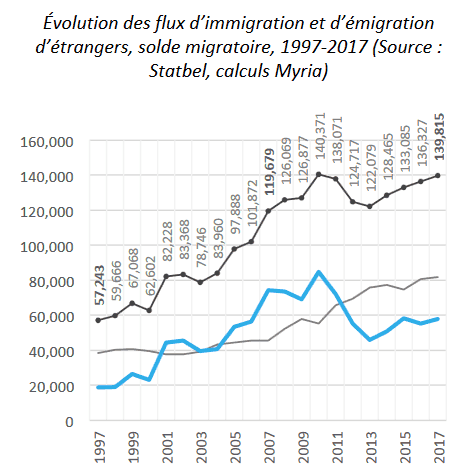

Since the end of the 1980s, Belgium has been experiencing a new migratory wave. Whereas the annual flow had been relatively stable between the 1950s and 1980s, with yearly arrivals of between 40,000 and 60,000, family reunification and asylum requests significantly increased the arrivals of foreigners. Over a million of them thus entered Belgium legally between 2000 and 2010.

Belgian migratory trends. Dotted line: immigration. Thin line: emigration. Solid light blue line: net migration.

Between 2009 and 2011 alone, family reunification, which accounts for about half of residence permits, enabled 121,000 foreigners to legally settle in Belgium. A Belgian senator, Alain Destexhe, speaks of family reunification’s “domino effect,” because of the different ways it gives for family members to come from abroad.

Since 2007, the annual number of foreigners arriving in Belgium has always been over 100,000. In 25 years, the immigrant population (of foreign or Belgian nationality) has doubled. Annual growth of the foreign-origin population is estimated at between 1% and 5%. As of 1 January 2018, of Belgium’s 11.3 million inhabitants, 16.7% were born abroad (1.9 million people). These figures do not take into account unidentified illegals, nor the asylum-seekers who are registered on the waiting lists.

The concentration of foreigners is especially visible in the big cities. For example, in Brussels, foreigners are almost as numerous as Belgian citizens. The city of Antwerp now has more immigrants than natives.

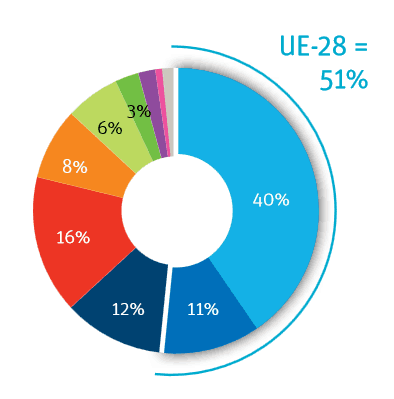

Origin of the foreign-born population in Belgium. Light blue: EU-15. Mid-blue: 13 new EU states (Eastern Europe). Dark blue: non-EU Europe (including Turkey). Red: North Africa. Orange: Sub-Saharan Africa. Light Green: West Asia. Dark Green: East Asia. Purple: Latin America. Pink: North America. Grey: Other.

Asylum-seekers: a secondary flow

In addition to illegal immigration, Belgium is, like France, experiencing the “secondary flows” of asylum-seekers. More and more asylum-seekers in Belgium are not fresh arrivals on the European continent. Their request for asylum was rejected in another country and they try their luck in Belgium. This phenomenon, which shows the bankruptcy of the European asylum “system,” is due to tougher migratory policies in the Scandinavian countries and Germany. It is estimated that one third of asylum-seekers practice this kind of “desk-hopping.” More broadly, between 1991 and 2015, some 517,000 asylum requests have been made in the country.

The origin of the immigrants has changed

If Europeans still make up the majority of the foreign population, Turks (155,701 people as of 1 January 2016) and Moroccans (309,166) represent significant contingents. Among the foreigners who have recently acquired Belgian citizenship, these two nationalities are in the lead.

According to the Pew Research Center, the Muslim population represents 7.6% of the Belgian population, almost 796,000 inhabitants. Depending on the migratory policies that are chosen in the next years (whether zero migration or a controlled opening of borders), the American think-tank estimates that the Muslim population could make up between 11% and 18% of the population by 2050.

The cost of immigration

In 2018 alone, 23,400 people in Belgium asked for international protection [under asylum]. The annual cost of asylum-seekers into terms of basic welfare has risen from 120 million euros in 2014 to 200 million euros in 2018. One must add to these figures the cost of welcoming asylum-seekers, which more than doubled between 2014 and 2016, rising to 524 million euros.

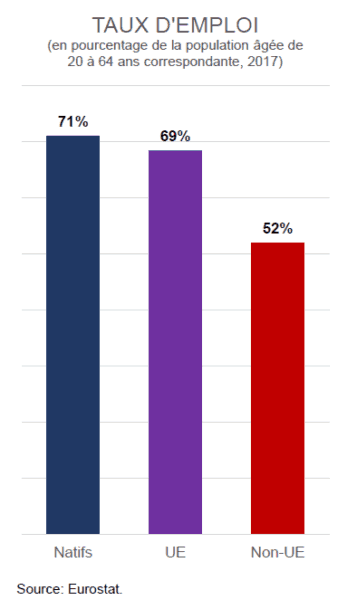

More generally, the employment rate of immigrants from outside the European Union is 20 points lower than that of natives. Whether as a cause or consequence of this, 80% of those receiving social assistance are of non-Belgian origin, according to a Belgian academic, Bea Cantillon.

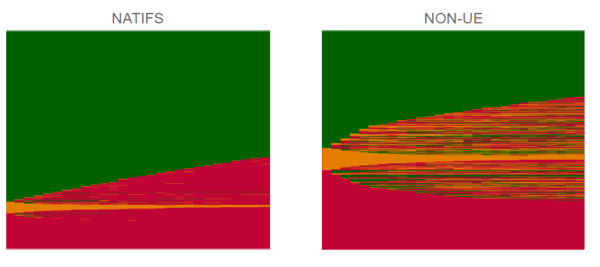

Employment patterns of representative samples of Belgian natives and non-EU migrants between 30 and 64 years of age between 2008 and 2014. Each line represents one individual. Green: working. In Orange: unemployed. Red: inactive (not seeking work). Source: Eurostat.

“Belgium will become Arab”

This prediction did not come from a dangerous conspiracy-theorist. It was expressed by a journalist, Fawzia Zouari, in the pages of the magazine Jeune Afrique [“Young Africa”] to sum up “the Islamization of minds,” in particular among of the young generation of Muslims. Though the Muslim population remains a minority, its importance is indeed growing and especially is becoming visible. Islamization is visible in several ways: in beliefs, behaviors, religious practice, and political life.

A Shiite political party named “ISLAM” was formed in 2012. It calls for the imposition of Islam’s strictest teachings: no shaking of hands between men and women, banning of mixed-sex schools and public transport, the wearing of the headscarf from the age of 12, etc, as well as the imposition of Sharia law. This political party’s [initial] electoral results are for now “anything but ridiculous,” as noted by a journalist in the magazine Le Vif [breaking the 4% threshold in the notorious Brussels neighborhood of Molenbeek, for instance] and the strict conception of Islam is progressing in Belgium.

According to a 2017 study by a Belgian foundation, 33% of Belgian Muslims do not like “the West’s culture, customs, and way of life” (women’s autonomy, alcohol, eroticism, etc), whereas 29% consider that “the laws of Islam are superior to Belgian laws.” A 2011 study highlighted the anti-Semitism of about half of the Muslim high-school students in Brussels who were polled.

The State Security Service (the Belgian international intelligence agency) observed recently an increase in groups and activities linked to Salafism, Islam’s most radical branch. One hundred Salafist organizations have been counted on Belgian soil. The mayor of Brussels for his part asserted in 2017 that “all of the mosques [in Brussels] are in the hands of Salafists.”

A shift in migration policy

Unlike France, which recently extended the right to asylum and to family reunification, Belgium has restricted these options since 2011. The Secretary of State for Asylum and Migration between 2014 and 2018, Theo Francken of the New Flemish Alliance [N-VA, a pseudo-nationalist conservative party], took a series of measures to reduce migratory flows: a strengthening of border checks and the expelling of illegal immigrants, a media campaign discouraging potential migrants from emigrating, measures to prevent asylum requests from being used to illegally settle in the country, etc.

The coalition government in power did not survive the signing by the Belgian authorities of the Marrakesh Pact on migration: at the end of 2018, the N-VA announced it was leaving the government and the country entered a new period of [political] instability. In contrast with the often politically-correct media, many voters took the opportunity of the recent European elections to vote for firmly anti-immigration party lists: the Flemish Movement [VB, a nationalist party] received 18.5% of the vote and the N-VA 27.2% [within Flanders].

Prospects

Whereas the Kingdom of Belgium has been rocked by secessionist tendencies over the past decades, dividing Flemings and Walloons, the country is now confronted with new challenges: mass immigration and the rise of political-religious demands from a part of the Muslim community. The country’s cohesion is more than ever being put to the test.