The Disuniting of America

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, April 1992

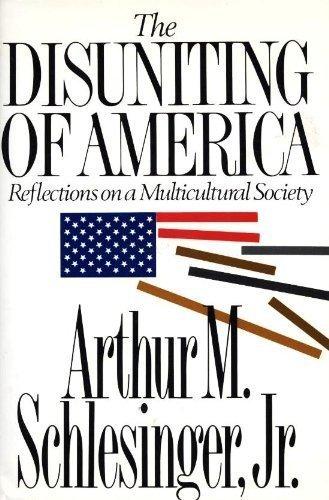

The Disuniting of America, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., W. W. Norton & Co, 160 pp.

Arthur Schlesinger is a distinguished historian best known for A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House. He is an unabashed liberal, and has seen much of what he hoped for come to pass: civil rights laws, affirmative action, non-white immigration, and “inclusion” of all kinds. But Professor Schlesinger is a thoughtful liberal, and he is genuinely worried. He sees that non-whites are repudiating the majority culture as never before, and he fears that if the current ethnic upsurge continues it could tear the nation apart.

The Disuniting of America may be a more important book than Prof. Schlesinger realizes, for it can be read as the first line of an epitaph — an epitaph to the disastrous policies that destroyed the United States of 40 years ago and that threaten the nation’s European character. Prof. Schlesinger still claims to believe in the magical capacity of the United States to transform Guatemalan refugees and Haitian boat people into admirers of Thomas Jefferson, but the scales are beginning to fall from his eyes. “[T]he mixing of peoples [will be] a major problem for the century that lies darkly ahead,” he warns. Even liberals are beginning to notice that something has gone seriously wrong with the great American experiment in multi-racialism.

Misuses of History

Because Prof. Schlesinger is a historian, it is natural that his book should be about the ways in which non-whites, especially blacks, are using invented histories as a way to carve out separatist identities. He fully recognizes the extent to which history is the basis of a nation’s understanding of itself, and quotes the Marxist historian Eric Foner: “A new future requires a new past.” Every non-white group in the country is peddling its own version of American history and hopes to use it as a weapon against the white man.

Blacks have taken the lead in this game, and Prof. Schlesinger neatly lays bare the lunacies and contradictions in what they say. The ostensible reason for Afrocentric history is that “Eurocentric” history is a pack of lies that insults and demeans blacks. Sermons about a glorious African past will transform ghetto punks into noble black men. Prof. Schlesinger despises this attempt to turn history into therapy.

In any case, there is no evidence that America’s admiration for ancient Greece ever gave Greek immigrants any intellectual or moral advantages. Jews and Asians have done very well in America without public schools to tell them how wonderful their ancestors were. Nor is there any evidence that “Eurocentric” education did any damage to W.E.B. DuBois, Ralph Ellison, or Martin King. Prof. Schlesinger suspects that Afrocentrists are driven as much by hatred of Western Civilization as by any real hope that new history books will keep young blacks from drugging themselves and shooting each other.

And yet, much as they claim to despise European culture, one of the Afrocentrists’ main aims is to prove that their ancestors created it. Black Egyptians are supposed to have invented everything from geometry to airplanes, only to have this wonderful knowledge stolen form them by Greeks. As Prof. Schlesinger points out, knowledge cannot be completely removed from its owner the way an object can; yet the Afrocentrist view requires us to believe that whatever the Greeks learned, the Egyptians thereupon ceased to know.

Ultimately, however, as even many blacks realize, it is folly to think that a knowledge of hieroglyphics or Egyptian cleansing rituals will do an American child the slightest good if he can’t read English. This doesn’t worry the Afrocentrists; they are educating Africans-in-exile, not Americans.

Another trend that Prof. Schlesinger laments is bilingual education. As he correctly points out, its effect — and perhaps its purpose — is not to teach immigrant children English but to keep them immersed in their mother tongues for as long as possible. The new waves of Hispanics are no more enchanted with the idea of adopting Anglo culture than are blacks. Prof. Schlesinger quotes one Hispanic who puts it this way: “The era that began with the dream of integration ended up with scorn for assimilation.”

What Will Hold the Center?

Prof. Schlesinger seems genuinely wounded that non-whites are turning up their noses at his culture just when he has been at such pains to make it “inclusive.” He also sees it as a betrayal of one of America’s most central doctrines: “the unifying vision of individuals from all nations melted into a new race.” He concludes with the uncertain hope that by reasserting Western values, an increasingly disparate America can be forged, once more, into a new unity.

Prof. Schlesinger’s disappointment and confusion stem from his own version of an invented American past, in which multi-racialism was, somehow, always the ultimate goal. Although it is perfectly clear that the Constitution was written for whites and not for blacks or Indians or anyone else, Prof. Schlesinger shares the near-universal view that multi-racialism was a predestined consequence of American democracy. To point out that this was nothing of the sort is to point out the obvious; racial equality, integration, and non-white immigration were radical departures from everything that Washington, Lincoln and even Wilson believed in. The “tolerance” and “inclusion” that are supposed always to have characterized America are entirely new doctrines.

Prof. Schlesinger sees the present as no different from the past; just as European ethnics blended together to become a new people, so will the new non-white immigrants. He concedes that race is a greater barrier to blending than was European nationality, but says he believes that “the historic forces driving toward ‘one people’ have not lost their power.” Of course, there have never been any historic forces driving blacks, whites, Indians, and Hispanics toward “one people.” They may have lived within the same national boundaries, but they have always remained distinct.

An obvious first step to counter the ethnic divisiveness that Prof. Schlesinger fears, would be to stop immigration, or to limit it to the European stocks that did become “one people.” This idea must be rejected, we are told, because it “offends something in the American soul.” Even if this were true — repeated polls show that Americans think the country has enough immigrants — Prof. Schlesinger surely understands that the forces of divisiveness could extinguish America’s soul.

Prof. Schlesinger is still a prisoner of the view that America is uniquely exempted from the lessons of history. Although he writes fearfully of renewed ethnic conflicts abroad, he believes that America can dispense with the ancient ingredients of nationhood: common religion, common tongue, common heritage, common ancestry. What, then, makes Americans American?

Democracy to the Rescue

Prof. Schlesinger, like so many others, falls back upon a national identity so threadbare, so improbable, that only the most credulous could believe in it. The “American democratic faith,” he says, is “what binds all Americans together.” Ours is a democracy in which most citizens cannot name their congressmen, in which not one in 500 can name his state legislator, in which Presidents are elected with the votes of less than a quarter of the electorate. Ours is a democracy in which voters despise politicians; one in which men of wisdom and integrity do not even enter, much less win, elections. Democracy will bind us together?

There are European countries in which democracy actually presents voters with real choices, where a far higher number of citizens vote, where men of some stature are voted into office. But no, democracy is America’s unique gift and treasure.

And are we to assume that Mexican peasant-women have their babies in American hospitals so that their children will benefit from the Bill of Rights and the separation of powers? Will democracy bind Cambodian tribesmen to the bosom of America any more successfully than it has Hopis and Navajos? Non-whites come to this country because they want jobs, money, and welfare, not because they want to join the PTA and become registered Democrats.

Not even the people who invented American democracy feel about it as Prof. Schlesinger thinks complete strangers will. It was not an appeal to representational government that sent Pickett’s men up the rise at Gettysburg, but the cry, “For Virginia; for your wives and sweethearts!” The marines didn’t land on the beaches of Guadalcanal, full of devotion to the Constitution, but of hatred for the people who bombed Pearl Harbor.

The unifying power of democracy is nothing compared to that of blood and soil. Non-whites will not give up their racial birthright in exchange for the ballot. For blacks and Hispanics, democracy is a racial head-count, a chance to push out the white man and replace him with one of their own. Increasingly, in America, the very democracy that Prof. Schlesinger thinks will bind us is numerical proof of how divided we are.

On the last page of his book, Prof. Schlesinger writes: “Our task is to combine due appreciation of the splendid diversity of the nation with due emphasis on the great unifying Western ideas of individual freedom, political democracy, and human rights.” What does this fine-sounding sentence even mean? It is precisely in the name of freedom and human rights that non-whites insist on going their own ways.

Nor will history save Prof. Schlesinger’s “splendidly diverse” America. As he writes on the next-to-last page, “People with a different history will have differing values. But we believe that our own are better for us. They work for us; and for that reason, we live and die by them.” This is the very thing an Afrocentrist might say! These are the very words on which Prof. Schlesinger’s unity in diversity will founder.