A Land of Their Own

James P. Lubinskas, American Renaissance, April 1999

The founding fathers, like many other great men in American history, recognized the problems of multi-racialism and wanted to avoid them. Some of this country’s most prominent 19th-century leaders supported the efforts of the American Colonization Society to help blacks return to Africa. Throughout American history whites have distanced themselves from blacks, sometimes by custom, sometimes by law.

It is less well known that blacks also have a long history of separatist and “back-to-Africa” movements. Some of these were attempts to escape slavery or second-class citizenship, but others were expressions of black pride and racial nationalism. What they all had in common was the understanding that multi-racialism does not work, and that the best hope for blacks was that they be free to shape their own destiny.

Although Marcus Garvey (1887–1940) was the best known and most influential of the black separatists, several lesser-known men were actually more successful — sometimes remarkably so — in helping American blacks move to Africa or establish black communities in the United States. Today, most blacks see the advantages of remaining within the larger white society — from which, unlike whites, they can withdraw into self-consciously racial groups and organizations whenever they like — but there are still many who would prefer complete separation.

Early Efforts

Paul Cuffee (1759–1817), a free, half-black, half-American Indian Quaker from Massachusetts, started the first black separatist movement in 1816. He concluded it was best for American blacks to leave the country rather than try to change it, and managed to get the financial backing from the British government to transport 38 free blacks to Sierra Leone. This West African nation had been established by the British as a haven for free and escaped slaves. Originally a private preserve of abolitionists and philanthropists, the government took it over in 1807 after banning slavery throughout the empire.

These movements recognized that multi-racialism does not work, and that the best hope for blacks was that they be free to shape their own destiny.

Cuffee died a year after this first voyage, unable to carry out his plans to resettle more blacks. It would be almost 40 years before another serious movement arose to continue his work, but two specific events revived separatist sentiment among the leading blacks of the mid-19th century: Liberian independence and the Fugitive Slave Act.

In 1847 Liberia declared independence. The country’s leaders were free American blacks who had been transported to Africa by the American Colonization Society. Thanks to the help and financial support of the ACS, the colony had been a success. Blacks were able to go to Africa without fear of starving or being killed by hostile natives and, what is more, Liberia was governed by blacks. “Back to Africa” was no longer just a dream.

Just three years later, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which allowed owners of runaway slaves to reclaim them even if they escaped to free states. This was a great setback even for northern blacks, since there were cases of free blacks being taken into slavery either mistakenly or deliberately for the reward money offered for escaped slaves. The act symbolized the precarious status of blacks, and had the effect of increasing black emigration to Canada.

Spurred by this legislation, a national black emigration convention in Cleveland in 1854 drew the leading separatists of the period. Describing their situation as one of “disappointment, discouragement, and degradation,” because of the continuation of slavery, they discussed emigration — though they decided against leaving the Western Hemisphere. Other black emigration conventions were held in 1856 and 1858 though no relocations ever resulted from them.

One person at the initial convention was a physician named Martin R. Delany (1812–1885). He had originally proposed a “Caribbean Negro Empire,” but by 1859 was the chief commissioner of a party exploring the Niger Valley in West Africa. Delany came up with a plan to transport blacks to Africa and grow cotton. The profits would not only sustain the African economy but would cut into the profits of slaveholders in America. He succeeded in signing land treaties with African chiefs but his project was stalled by the start of the Civil War and was later abandoned. Many blacks expected the war to bring about a radical change in the status of blacks, and this dampened colonization and separatist sentiment.

With the end of Reconstruction, blacks realized that although they were free, most whites did not want them. Abraham Lincoln himself had called blacks “a troublesome presence,” and urged them to resettle in Latin America. By that time the ACS had lost its momentum but several black leaders were still calling for colonization in Africa. Richard H. Cain, an influential black minister and newspaper editor from South Carolina, claimed in 1876 that “thousands” of blacks in the state would leave for Liberia if transportation were furnished them. Martin Delany, by that time a judge in Charleston, lent his support, and the result was the Liberian Exodus Joint Stock Steamship Company. It acquired a ship named the Azor and set sail for Liberia with 206 blacks on board. Twenty-three died of disease during the “middle passage,” and this disastrous first voyage sent the poorly-managed company into bankruptcy. The deaths reminded blacks of the dangers of relocating to Africa and cooled the ardor of would-be emigrants.

Not all separatist movements involved returning to Africa. Benjamin “Pap” Singleton (1809–1892), an illiterate former slave, settled 7,500 blacks in Kansas during the 1870s. According to Singleton, blacks needed land of their own. He argued that once the war was over, “the whites had the lands and the sense an’ the blacks had nothin’ but their freedom.” Known as “the father of the Black Exodus,” Singleton was a kind of black Horace Greeley, urging his people to go west and grow up with the country. Singleton found an audience in the huge camps for newly-freed slaves that the Union army set up after the war. Here he worked as a coffin- and cabinetmaker, and urged destitute ex-slaves to leave the South. In 1872 he started a homestead association, and in 1875 he established the Tennessee Emigration Society, which left no doubt as to why blacks should leave: “To the white people of Tennessee, and them alone, are due the ills borne by the colored people of this State.” The society sent delegates to Morris County, Kansas, to establish a “colony” for blacks, which was named Dunlap. A few years later, Singleton plastered posters around Nashville announcing, “Leave for Kansas on April 15, 1878,” and over 2,000 blacks joined the initial exodus. Reaction from whites was mainly ridicule: “A foolish project,” remarked the Nashville Union and American. Even the famous black abolitionist Frederick Douglass criticized the move, saying that blacks should stay in the South and fight for equality.

Kansas was not the Canaan Singleton was hoping for. Whites did not want thousands of blacks pouring into the state and were hostile to the settlers from Tennessee. Singleton eventually gave up on his plans for black autonomy in America and formed the United Transatlantic Society in 1885 to help blacks return to Africa. His society passed resolutions favoring “Negro national existence,” and called a separate nation necessary for black survival. Although Singleton died in 1892 without having led any blacks to Africa, for a man who could not read or write, and who spent 59 of his 83 years as a slave, his life was one of extraordinary vision and achievement.

Black separatism produced its share of colorful characters. One of the most colorful was a self-styled African chief named Alfred Charles Sam, who was active around the time of the First World War. Though he called himself Chief Sam, he was not from Africa but from one of the all-black communities of Oklahoma. The cotton depression of 1913 increased interest among blacks in Sam’s back-to-Africa schemes. He traveled extensively, selling stock in his Akin Trading Company and forming clubs to generate support for his plans. He filled the minds of gullible blacks with stories of bread-bearing trees and diamonds littering the ground after rain storms. The NAACP, which opposed the emigration movement, called Chief Sam a charlatan.

Sam, who compared himself to Moses, did manage to accompany one shipload of blacks to the promised land. In 1914, his ship, the Liberia, set sail from Galveston, Texas, with sixty passengers. In the Gold Coast (now Ghana), they encountered tropical diseases rather than bread-bearing tress, and most of the settlers returned to the United States. Sam, however, stayed in Africa until his death several years later.

Marcus Garvey

The largest black separatist movement in American history was led by Marcus Garvey, who founded what may have been the first such movement that was not just an escape from whites but a real expression of black pride. Born in Jamaica in 1887, Garvey moved to England in his early twenties, where he worked for a magazine called African Times and Orient Review that advocated home rule for Egypt. Returning to Jamaica in 1914, he founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), with considerable support from whites. Its original goal was not separation but unity and “to raise them [blacks] to the standards of civilized approval.” It’s motto was “One God! One Aim! One Destiny!”

Marcus Garvey

Garvey moved to the United States in 1916 in the hope of raising money from black leaders to start a school in Jamaica modeled on the Tuskegee Institute. His thinking changed as he got to know America. Disillusioned by anti-black race riots and what he saw as obstacles to black progress, he gave up on integration and by 1919 was calling for separation. Garvey believed that racial equality was impossible unless the races were on the same economic level, but thought blacks could not compete because they did not control institutions. Accordingly, he believed blacks must have their own institutions in a separate homeland, which was to be in Africa.

Garvey advocated the theory of “race first,” meaning that black people worldwide should put racial interests before all others. The official UNIA newspaper Negro World was the most widely read black paper in America, and had as its motto “Up, you mighty race!” Directing his appeal to darker-skinned blacks, Garvey exalted everything African and even disparaged lighter-skinned blacks. Much like modern-day black radicals, he condemned Western civilization but claimed that blacks had actually created it. He formed his own “African Orthodox Church,” and portrayed God, Christ, and Mary as black saying, “only the Negro’s devil would be white.” He was the first well-known proponent of “black is beautiful,” and may have originated the phrase.

He called for separate schools that taught black pride and history. Though he would later work with the Ku Klux Klan to promote separation, he wanted to avoid any alliances with other races. The UNIA supported racial purity and forbade intermarriage. Garvey wrote, “I am conscious of the fact that slavery brought upon us the curse of many colors within the Negro race, but that is no reason . . . [to] perpetuate the evil. . . .” Blacks could not even have pictures of whites in their homes.

Garvey’s main rival was the light-skinned, integrationist W.E.B. Du Bois (1868–1963), whom he criticized for “advocat[ing] racial amalgamation or general miscegenation with the hope of creating a new type of colored race by wiping out both black and white.” Du Bois, in turn, claimed that “Marcus Garvey is, without doubt, the most dangerous enemy of the Negro race in America and the world,” and was “either a lunatic or a traitor.” Indeed, when Garvey went to New Orleans to meet with leaders of the Ku Klux Klan, he told them, “This is a white man’s country. He found it, he conquered it, and we can’t blame him if he wants to keep it. I am not vexed with the white man of the south for Jim Crowing me because I am black. I never built any street cars or railroads. The white man built them for his convenience. And if I don’t want to ride where he’s willing to let me ride, then I’d better walk.” Though he claimed he was just trying to get blacks to build their own infrastructure, such statements infuriated black integrationists.

In 1921 Garvey announced his plan for an “Empire of Africa” with himself as Provisional President. He would model his “empire” on Europe, complete with Dukes of the Niger, Knights of the Nile, and Knights of the Distinguished Service Order of Ethiopia. He designed a red black and green flag for his empire and it’s national anthem was, “Ethiopia, Thou Land of Our Fathers:”

Ethiopia, Thou land of our fathers, Thou land where the gods loved to be, As storm cloud at night suddenly gathers Our armies come rushing to thee. We must in the fight be victorious When swords are thrust outward to gleam; For us will the vict’ry be glorious When led by the red, black and green.

Advance, advance to victory,

Let Africa be free.

Advance to meet the foe

With the might

Of the red, the black, and the green.

Red was the color of blood, black the color of the race, and green was the color of leafy Africa. These are still the colors of the pan-African movement.

Garvey supported Senator Joseph France who wanted the United States to forgive all World War I debts in return for the defeated nations’ African colonies, which would become an independent African-American nation. Garvey planned to build it up into an industrial power and conquer all of Africa, thus freeing it from European colonizers: “we mean to retake every square inch of the twelve million square miles of African territory belonging to us by right divine.”

In the early twenties, Garvey claimed that six million blacks world- wide were UNIA members and that it had 700 chapters in 38 states. The association owned a chain of restaurants and grocery stores, laundries, a hotel, and a printing press. Perhaps the height of his power was a 1920 international UNIA convention with delegates from 25 countries, which climaxed with a parade of 50,000 through the streets of Harlem.

To show that blacks could own and operate businesses (and ultimately to transport blacks to Africa), Garvey established the Black Star Steamship Line (BSL). Though whites helped to get the line started, it had only black stockholders and officers. The company sold five-dollar stock certificates exclusively to blacks. The BSL raised over $600,000 this way and acquired three ships. This was an important achievement for black Americans and thousands showed up in New York to see the ceremonial launch of the first ship, the Yarmuth. Garvey told his followers, “Remember, the Black Star Line Steamship Corporation is not a private company. The ships that are owned by this corporation are the property of the Negro race.” Garvey operated the ships commercially in the Caribbean — complete with all-black crews — as a symbol of black success.

The Yarmuth, with black captain Joshua Cockburn at the helm, made three trips to the Caribbean, carrying passengers and cargo. Blacks came out in crowds to greet the ship wherever it docked. One officer wrote, “I was amazed that the Yarmuth had become such a symbol for colored people of every land.” A collision in 1920, just one year after the ship was acquired, put the Yarmuth out of service.

A second ship, the Shadyside, ferried passengers along the Hudson River for one summer, but during the winter of 1920 it split a seam during an ice storm and sank. A third ship, the Kanawha, was plagued by mechanical problems and chronic incompetence by its crew. Several trips were scuttled because of problems with the boilers and engines. Garvey accused the captain and chief engineer of drunkenness. The officers often gambled on board, and the captain even interrupted a voyage to make an unscheduled stop in Norfolk, Virginia, to see his wife. After an intake of sea water ruined the boilers the crew left the Kanawha for junk in a Cuban port.

What was to be a shining symbol of black efficiency became a symbol of mismanagement. The line lost $47 million, and by 1922 was in bankruptcy. Garvey complained that “graft, thievery and sabotage” ruined the BSL, and accused the captains of hiring and overpaying their friends and family. He accused officers of deliberately damaging ships so they could get kickbacks on repairs. Captain Cockburn of the Yarmuth admitted to getting an $8,000 kickback on a $16,000 engine repair. “That man Cockburn!” said Garvey, “May God damn him in eternal oblivion. That man had in his hands the commercial destiny on the seas of the black man. He sold it, every bit of it, for a mess of pottage.”

In 1922, Garvey’s critics, including his old nemesis Du Bois, called for a complete investigation of the BSL, and Garvey was charged with mail fraud for selling stock in the already bankrupt shipping line. Du Bois called for him to be “locked up or sent home.” At his 1925 trial he acted as his own lawyer, and was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. While he was still in prison, the UNIA sued him for spending association money on himself. In 1927, responding to a campaign by Garvey supporters, President Coolidge pardoned him and deported him to Jamaica. Garvey eventually made his way to London where he expressed profound admiration for Benito Mussolini. Garvey claimed authorship of Mussolini’s philosophy, saying “we were the first fascists.” However, in Britain the father of black nationalism and the most popular black separatist could not draw crowds, and was eventually reduced to soap-box appearances at Hyde Park Corner, where he became a regular attraction. He died in 1940 in virtual obscurity.

Separatism Today?

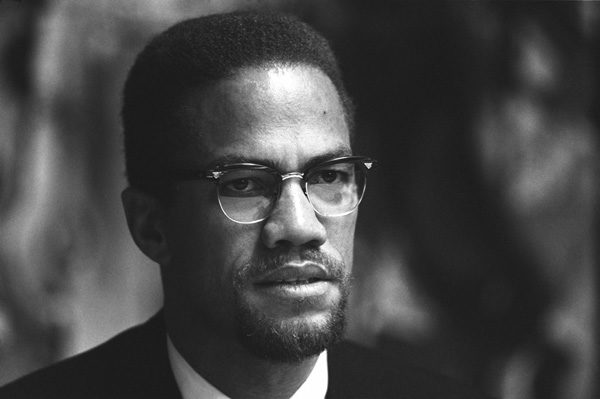

After the collapse of the Garvey movement, black separatism lost ground to integration and the civil rights movement. In the early 1960s, however, black muslim Malcolm X (1925–1965) revived the idea. He even met with the Ku Klux Klan to ask its help in starting a homeland. Though he is generally said to have embraced integration after his pilgrimage to Mecca, he would accept whites only if they converted to Islam.

Malcolm X (Credit Image: © MediaDrum via ZUMA Press)

Elijah Muhammad (1897–1975), the founder of the Nation of Islam, was also a firm believer in racial separation. In 1962, he invited American Nazi Party leader George Lincoln Rockwell to address the nation’s annual convention. Muhammad praised the racial separatism advocated by Rockwell, and sharply criticized black integrationists.

Today it is Louis Farrakhan, who took over the Nation of Islam after Muhammad’s death, who is the leading black separatist. In every issue of The Final Call, the nation’s official newspaper, there is a page that lists the organization’s beliefs. The most important are written in bold-face type and include point number four:

We want our people in America whose parents or grandparents were descendants of slaves, to be allowed to establish a separate state or territory of their own — either on this continent or elsewhere. We believe that our former slave masters are obligated to maintain and supply our needs in this separate territory for the next 20 to 25 years — until we are able to produce and supply our own needs.

However, only blacks can choose separation:

We want every Black man and woman to have the freedom to accept or reject being separated from the slave master’s children and establish a land of their own.

We know that the above plan for the solution of the Black and white conflict is the best and only answer to the problem between two people.

The Nation of Islam also states, “We believe that the offer of integration is hypocritical and it is made by those who are trying to deceive the Black peoples into believing that their 400-year-old open enemies of freedom, justice and equality are, all of a sudden, their “friends.’ Furthermore, we believe that such deception is intended to prevent Black people from realizing that the time in history has arrived for the separation from the whites of this nation.”

Although this sounds unequivocal, there are good reasons to doubt Mr. Farrakhan’s sincerity. Years ago, he offered to take the blacks from America’s jails and lead them to a new home in Africa, but he no longer talks about separation. His 1995 “Million Man March” drew between 400,000 and 1,000,000 blacks to Washington, D.C., and the world media covered his speech to this enormous crowd. Though he spoke for several hours, not once did he mention separation.

Given the subservience of today’s whites and their compulsion to promote the interests of every race but their own, blacks have little reason to leave. Because whites are so easily intimidated, Mr. Farrakhan has great leverage so long as his movement remains within the United States. The merest hint of separation is a powerful weapon against anyone too weak to call his bluff. Many blacks must also know that a black-run nation would be plagued with the same problems as black-run schools and cities. Perhaps it is better to live in an efficient, industrialized country run by terrified whites than to be masters of Haiti or Liberia.