Haiti: Then and Now

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, March 23, 2012

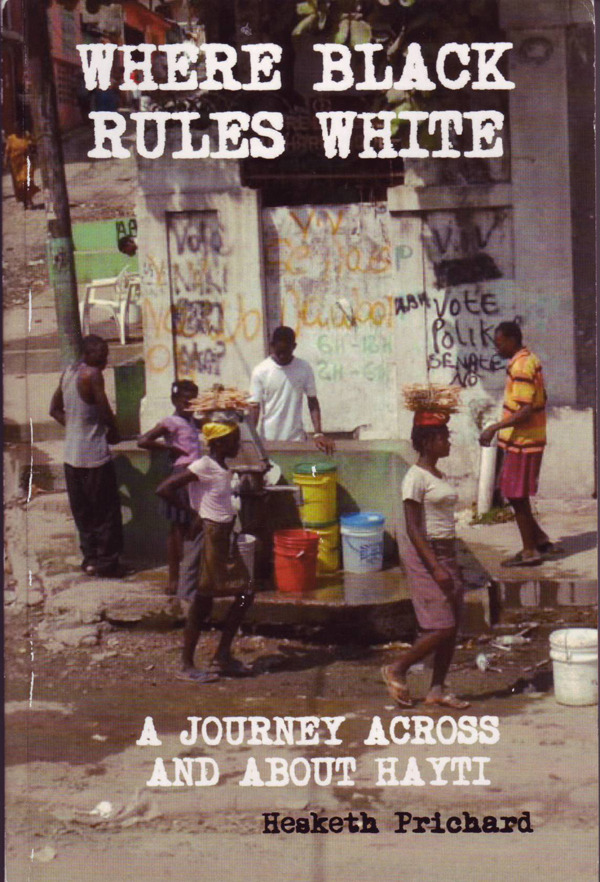

H. Hesketh Prichard, Where Black Rules White: A Journey Across and About Hayti,

Ostara Publications, 140 pp., £10.20 (soft cover)

In 1899, the British explorer, hunter, and travel writer Hesketh Prichard (1876 – 1922) became the first white man to cross the interior of Haiti since 1803, the year before Haiti declared independence from France. He was commissioned by press baron Cyril Arthur Pearson to report on the country as part of Pearson’s launch of a new paper, the Daily Express. Prichard sent back a series of reports, which became the basis of this book, which first appeared in 1900.

Prichard spent several months in Haiti, and wrote with what appears to be objectivity, but he did not hesitate to pass judgment. By today’s standards he was sometimes harsh, but a number of his observations were frankly admiring, and he saw more promise in the country than today’s reader might expect. The book remains well worth reading, and thanks to this attractive reprint by Ostara Publications, it is readily available.

‘White Man’s Grave’

At the time of Prichard’s trip, he estimated that there were perhaps 500 whites living in the country, but they rarely left the coastal cities. The cities, however, were what Prichard liked least about Haiti. His first step on land was at Jacmel, the principal port of southern Haiti. “The street was full of men and women, screaming, gesticulating, and shouting,” he wrote. “The din was incredible.” He slept at the British consul’s house because there was no hotel.

In all the cities he visited, he found rubbish everywhere, and “road mending appears to be a lost art.” The capital, Port au Prince, he called “about the filthiest place in the world,” adding, “I have seen more than one of those unhealthy spots to which is attached the sobriquet of ‘White Man’s Grave,’ but none of them have the invitation to disease written so plainly across their faces as this city of Port-au-Prince.” Its surroundings, however, he found charming: “Viewed from afar you would call it one of the most beautiful spots on God’s earth. But go down into the squalid streets, and you find the town is a fester, a scar made by man, as if it were of malice prepense, upon the natural loveliness of its environment.”

Prichard, who was a soldier and went on to write a still-in-print manual for snipers, took a keen interest in the Haitian military. He noted that soldiers ran the country, and that every man of any importance had the title of general. Most were appointed by the president — himself a general — but had never served in a lower rank. Prichard wanted to know how many generals there were, but the most recent statistics were more than 30 years old. In 1867 there were reported to be 6,500 generals, 7,000 officers, and 6,500 privates. Each general therefore would have commanded one private and one and one-thirteenth officers.

In the cities, generals often had prestige without power, but in the countryside they were dictators. Prichard wrote of one provincial general whose policy of executing all thieves completely rid his region of theft.

Prichard also found that “general” had become a form of respectful address to anyone; he was, himself, often addressed as “General.”

Close observation of as many military drills as possible led Prichard to conclude that the Haitian “is not naturally a soldier:”

What he cares for is the play at being a soldier; he loves the accoutrement, the uniforms, the gold lace — especially the gold lace. He has a passion for military titles, military bombast, military display. Even on his postage stamp a cannon sprawls menacingly in front of crossed flags; but there it ends.

And yet, Prichard also wrote that although the ragged, rarely-paid Haitian soldier showed little polish or discipline, all he needed was good officers: “[W]ith steady handling he could be turned out a first-class fighting man.”

A Scot, who captained the one functioning gunboat in the Haitian navy, also took this view. He and another white man, the first mate, commanded a crew of 175, who kept the ship in excellent condition. The navy had so few shells that the crew had to practice gunnery by tying rifles to their cannons and firing bullets, but the Scot was confident that although his men had never been in battle, they would serve well.

The many generals to whom Prichard spoke also believed their men “would fight like heroes,” and that Haiti could easily drive off any European power that dared to invade. The Boer war had begun in 1899, and the generals were convinced to a man that the Boers were black — after all, they lived in Africa — and that they would therefore rout the British. Prichard could not convince even an ex-minister of war that the Boers were white.

Prichard also took an interest in the police, whom he found cruel and utterly corrupt. Like soldiers, they were badly and irregularly paid, and many used their power to extort money. Prichard saw many arrests that seemed to him entirely arbitrary, and almost all were accompanied by a sound thrashing with a club called the “coco macaque.” “It is iron shod to add piquancy to its blows,” Prichard wrote, adding that “even the negro occasionally succumbs to its powers and has been known to die by the roadside or on his way to jail.”

Prisons were supposed to be off limits to foreigners, but Prichard managed to inspect at least one. The conditions, he wrote, “would disgrace the worst cattle boat that ever crossed the Atlantic.” Prisoners received no rations, so any man who did not get food from his family either begged or starved.

Race and race relations

Prichard reported that the police usually left whites alone, as did the general population of Haiti: “Her people, whatever may be their other faults, have not that knife-in-your-back instinct which permeates so many of the Spanish American republics.” However, any white who found himself before a Haitian judge “has no rights the black need respect.” Therefore, “it is nearly always far cheaper to submit to injustice than to try conclusions in a law court.”

Aside from diplomats, Prichard found that whites living in Haiti “cannot be called a particularly fine example of the aristocracy of colour,” but the Syrian traders who monopolized commerce, especially in the interior were worse. “They are a race unspeakable, living ten in a room, consummate cheats,” he wrote. “[T]hey are usurers and parasites sucking the blood from the country and in no way enriching their adopted land in return.”

Prichard found that the majority of Haitians — the pure Africans — hated the mulattoes. This was an old quarrel that dated back to mutual massacres during the wars for independence. Prichard found mulattoes more civilized and productive than blacks, and concluded that this only increased the resentment against them. All government employment, whether as judges or generals, was closed to mulattoes, who usually ran small businesses. The title of Prichard’s book refers not to the subordination of whites but of mulattoes.

Although Prichard does not seem to have paid much attention to Haitian social relations, he did notice that every man of any substance was a polygamist — though the actual formality of marriage was rare, even among the upper classes. “Wives to the negro are a source of wealth,” he wrote. “They work for him while he, with constitutional and ineradicable laziness, sits in the shade of his largest hut and smokes a pipe.” He concluded that “in Hayti [sic] there are three classes who work: the white man, the black woman, and the ass.”

Prichard arrived in the country with a great curiosity about voodoo, which he found very widespread. “In Hayti the nominal religion is Roman Catholicism,” he wrote, “but it is no more than a thin veneer; beneath which you find . . . a solid groundwork of West African superstition, serpent worship, and child sacrifice.” The priests and priestesses of voodoo were known as “papaloi” and “mamaloi,” corruptions of papa le roi and mama le roi (papa the king and mama the king). All Haitians believed these “kings” could kill at will, either by poisoning or with spells, so voodoo priests were essentially beyond the law. Prichard thought they had more influence over the lives of the people than the generals.

Many a night, Prichard heard the voodoo drum sounding in the distance, and he attended at least one ceremony. More than 200 people packed into a small house to admire the incantations and gyrations of a mamaloi. At what appeared to be the climax of the evening, she tore off the heads of six chickens and drank their blood. She sprinkled blood on the doors and gates of the house and then, to Prichard’s astonishment, drew the Christian cross in chicken blood on the foreheads of the devotees. There was much drumming and frenzied dancing, which went on for hours. Prichard had meant to stay to the end, but left early, defeated by the din.

Prichard believed that voodoo priests sometimes sacrificed a child — “the goat without horns” — which they cooked and ate, but he never saw this done. He wrote that the one reliable report from a white man was that of a priest who claimed to have blacked his face and hands and slipped into a ceremony, where he rescued the child at the last moment. Other observers from the period also report child sacrifice and ritual cannibalism.

Prichard thought the depredations of the papaloi and mamaloi perverted the country and held it back: “[They] encourage the worst tendencies innate in negro nature . . . . Until they are smitten down the country can never flourish.” If the witch doctors could only be eliminated, “the whole edifice of [voodoo] horror will crumble to pieces” and Haiti would be transformed.

The interior

Prichard found the Haitian interior very primitive: “Five miles inland, you lose touch with civilization, with the world.” He had been in Africa and noted that “the huts in which he [the Haitian] lives in the interior are the same as those in which his forefathers lived beside the Congo.”

Prichard’s first trip overland was from Jacmel to Port au Prince. He spent many days on horseback and lost track of how many times he had to cross rivers, but reckoned he had made 150 to 200 fordings — to cover a distance of only 25 miles, as the crow flies. He learned a national proverb: “When you see a bridge always go around it.” This was because bridges were likely to be broken or so rotten a man could fall through them.

Haiti still had magnificent forests that have since been felled to make charcoal, but for Prichard it seemed that “golden opportunities lie ripe to be plucked, but here is no hand to pluck them.”

In the country, he found people had only two pleasures, cockfighting and dancing to tom toms. “It is their passion,” he wrote of dancing. “Never are they too tired, never can a dance go on too long.” In the cities as well, there were dances every night, with galas put on by every class of citizen.

For ordinary Haitians of the interior, Prichard had both pity and high praise. Their material conditions were awful. They were “figures clad in little, the children clad not at all,” leading the “the sordid, purblind life of savages.” And yet their personal qualities were noble:

Of the peasant’s attitude towards the stranger in the more remote districts, I have nothing to say but good. His virtue of hospitality is beautiful. His politeness is beyond reproach. He is Nature’s gentleman in many ways, and though he is poor in worldly goods, he is rich in some of the higher qualities.

“The people cannot give you what they have not, but they do give what they have, and that with both hands,” he wrote, adding that country people were insulted when he offered to pay for hospitality. The cities swarmed with thieves and cheats, but the peasants were “a kindly, hospitable, good-hearted, song-loving, and a cheerful people.” He did not hesitate also to call them “ignorant and lazy,” but their greatest misfortune was that they were “brutally misgoverned.”

Whether because of misgovernment or something deeper, certain national traits have endured. In 1899, Haitians still spoke of the earthquake of 1842 that leveled the town of Cap Haitien. Afterwards, people poured in from the surrounding areas, not to help but to rape and rob. “What a people!” wrote Prichard, somewhat less generously than the Westerners who wrung their hands over similar behavior after the 2010 earthquake.

Pritchard’s study of the history of Haiti led him to believe that frequent revolutions and coups d’état changed nothing: “It seems impossible under black government for any undertaking or institution to be cared for, or kept up, or carried on. Some individual, in an ambitious moment, makes a start, but the beginning of any enterprise whatsoever is also the end; no one bothers to go on with it.” Prichard wrote that Haitians knew they were badly governed, but were convinced that colonization by whites would mean a return to slavery. Thus, they preferred the agonies of misgovernment by brutes.

At the end of the book, Prichard asked the basic question: “Can the negro rule himself?”

He had a good chance at it. He had one of the most beautiful and fertile islands in the world. He inherited good French laws. He had cities built for him by the French. And yet, Haiti has produced only one figure that deserves real admiration: Toussaint Louverture [the leader of the struggle for independence from France].

Prichard believed that Louverture “was actuated throughout his life by no other feeling than that of love for his country,” and wondered whether the mere fact that he existed at all might be proof that blacks could rule themselves. On balance, however, he concluded that Louverture was too rare an exception: “Certainly he [the Haitian] has existed through one hundred years of internecine strife, but he has never for six consecutive months governed himself in any accepted sense of the word.”

Haiti today

More than 100 years later, Haitians are still “brutally misgoverned,” and some people are still asking, if not in so many words, “Can the negro rule himself?” In 2004, Gabriel Marcella of the US Army War College proposed setting up an international protectorate to save Haitians from themselves. Claude Beauboeuf, an economist, predicted that 65 to 70 percent of the population would support what would be, in effect, recolonization. (Carol J. Williams, “Protectorate Touted to Mend Haiti’s Crippled Society,” Los Angeles Times, Dec. 25, 2004.)

He was probably right. Jamaica is not nearly the horror Haiti is — it has been independent since only 1962 — but a recent poll found that 60 percent of Jamaicans thought their country would be better if it were still ruled by the British. Only 17 percent disagreed. (“Poll: Most Jamaicans Believe UK Rule Better,” Yahoo! News, June 28, 2011.)

A 2011 Wall Street Journal article pointed to Zimbabwe as the classic case of independence gone wrong, and suggested that essentially all of black Africa should be recolonized. The article quoted an 1881 letter from King Bell and King Acqua of the Cameroons River, West Africa, addressed to British Prime Minister William Gladstone: “We are tired of governing the country ourselves . . . . [W]e think it is the best thing to give up the country to you British men who no doubt will bring peace, civilization and Christianity in the country.” The kings even said they were “quite willing to abolish all our heathen customs.” (Bret Stephens, “Haiti, Sudan, Côte d’Ivoire: Who Cares?” Wall Street Journal, January 11, 2011.)

Regnant egalitarianism forbids taking failed countries in hand, so they suffer as Haiti continues to suffer.