When Whites Hunted Blacks

American Renaissance, Thomas Jackson, October 2001

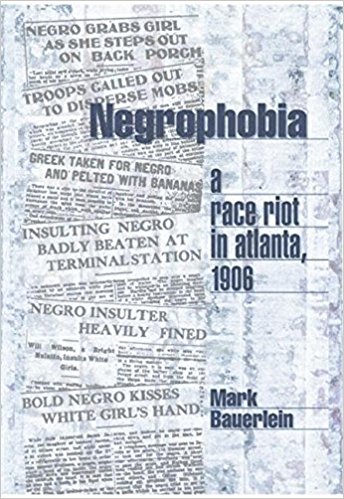

Mark Bauerlein, Negrophobia: A Race Riot in Atlanta, 1906, Encounter Books, 2001, 337 pp.

Since the 1960s, race riots have consisted of blacks burning and looting their own neighborhoods, and attacking any whites they find. Racial mob violence has become a black monopoly threatened only occasionally by Hispanic rioters.

It was not always so. From the period after the War Between the States until the 1940s, race riots meant whites attacking blacks, usually in black areas. The last such riot took place in Detroit on June 20, 1943, when white mobs fought blacks in various parts of town, and even launched motorized raiding parties into black neighborhoods. Twenty-five blacks and nine whites died, in a culmination of tensions that arose from a sharp increase in the black population.

Today, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Cincinnati remind us that blacks still riot, but it is now almost impossible to imagine the reverse: whites stampeding through a city attacking blacks. Recent race riots are therefore the exact opposite of what they once were. Whites, who used to pursue and terrorize blacks are now, themselves, pursued and terrorized. What has changed in the last 50 years to turn prey into predator? Outwardly, very little. Whites are still the majority population and hold most positions of power. Blacks are still more crime-prone, and more likely to be poor and uneducated. Psychologically, however, American race relations have been turned inside-out, and to reconstruct the racial context of 60 or 70 years ago is to paint a picture of what might as well be a foreign country. This is what makes Negrophobia so interesting. A book-length account of a famous, early 20th-century race riot that relies on contemporary documents cannot help but reconstruct a social order that has vanished. Mark Bauerlein, who teaches English at Emory University in Atlanta, cannot forego a certain amount of shocked commentary, but his study of the 1906 Atlanta race riot largely lets participants and observers speak for themselves.

In 1906, Atlanta had approximately 150,000 inhabitants, of which about one third were black. The city had never had a race riot. As it does today, it liked to advertise itself as more interested in money-making than race-baiting. In 1895, Booker T. Washington had given his Atlanta Compromise Speech at the Cotton States and International Exposition, in which he denounced blacks who clamored for political and social equality. Negroes, he said, would make better progress by working hard and winning the genuine respect of whites than by agitating for voting rights and the abolition of Jim Crow.

Atlanta was, of course, segregated. Ponce de Leon Park had a prominent sign saying “Colored persons admitted as servants only.” There was very little social mixing of the races and no interracial “dating.” Even chain gangs and prisoners the state rented out to private employers might work together but had segregated housing. Whites were matter-of-fact about the failings of blacks. An 1899 report by the Georgia Prison Commission concluded that “after forty years of freedom and education,” the negro is “more criminal than when he possessed no education whatever.”

Just as they are today, black slums were hives of degeneracy, and both whites and respectable blacks were prepared to say so. A city council report of the period described the Decatur Street area close to downtown as full of “squalid negro hovels that teem with vice and vermin.” Here were the flop houses, cheap bars, and prostitutes that attracted a large, exclusively black clientele. Even the Voice of the Negro described Decatur Street as “a dark, almost impenetrable mass of humanity writhing in the densest ignorance and lowest morality,” and another black author called Decatur Street blacks “the dregs, the scum, the menace of municipal life.”

It was Decatur Street that prompted the Atlanta Evening News to ask, in an editorial, “Who will penetrate the darkened recesses of the negro mind?” The Atlanta Georgian (there were four daily newspapers in 1906) ran the headline “What is the Destiny of the Negro Race? Extinction?” and went on to speculate that health conditions were so bad in the slums that blacks might well die out.

At the same time, people of all races made a clear distinction between the unregenerate “Decatur Street negro” and the industrious, church-going “Auburn Avenue negro.” Blacks provided useful services as domestics and understrappers, and the more capable and ambitious had established a genuine middle class. According to an 1899 count, Atlanta had 61 businesses owned by blacks. Auburn Avenue was the favored address for black high society.

Despite the existence of a black middle class, this was not an era in which Southerners had illusions about racial equality or the desirability of integration. On August 4, 1906, the editor of the Atlanta Georgian wrote: “The best and only way to provide a political freedom for the white man and a social protection for the white race and sanctity for the women of the white race . . . is by reducing the negro for his own protection and for his own welfare, to the acceptance of a place of inferiority until such time as he can be separated from the white race and removed to another territory.”

This was a time when politicians voiced sentiments about race unimaginable today. In his 1906 campaign for governor, Hoke Smith said: “Those negroes who aspire to equality can leave; those who are contented to occupy the natural status of their race, the position of inferiority . . . will find themselves treated with greater kindness.” The press attributed his victory to a strong stand on the need to keep blacks from voting. In his victory speech, he said “a constitutional amendment must be passed . . . providing for the protection of the ballot box . . . against ignorant and purchasable negro votes.”

Even in a period when blacks were held in a distinctly subordinate position, there was still enough black crime to drive whites out of the city. Prof. Bauerlein reports that by the turn of the century Atlanta had already seen considerable white flight. Young families fled to the suburbs, away from the negro menace, but lived in areas with plenty of shrubbery that could conceal prowlers. Men took the streetcar into town to work, leaving wives and children at home, and this proved an irresistible temptation to black criminals.

Newspapers put crime stories on the front page and did not pretend, as they do today, that the race of victim or perpetrator were unimportant. It was common to find stories with headlines like “Miss Mittie Waits Given Bad Fright by Negro at Spring,” “$1,600 Reward to Capture Negro,” “Girl Jumps Into Closet to Escape Negro Brute,” or “Bold Negro Kisses White Girl’s Hand.”

Black crime was much on the minds of whites, and many took justice into their own hands. When a rape was reported, hundreds of white men — many of them armed — descended on the victim’s home. Some combed the area looking for blacks who matched the perpetrator’s description, while others waited at the house, hoping to serve summary justice. One 1906 headline in the Constitution claimed, probably with some exaggeration, “Mob of 2,000 Gathered at the Lawrence Home Anxious to Burn Negro.”

Search parties would return with terrified blacks, whom they exhibited to the victim. If the woman said he was the culprit, it was touch and go whether the authorities could save him from the mob. Prof. Bauerlein writes that policemen often showed great courage and finesse in spiriting black rapists out of the hands of vigilantes. Another 1906 newspaper account described a case in which they failed: “In less than two seconds after the negro brute . . . had been identified by the young woman . . .

six bullets were tearing their way through his heart and he fell dying amid a solemn shout from half a hundred avengers.”

Although Southerners were sharply divided about the propriety of lynching, they were united in the view that violation of a white woman was a capital crime. They saw it not only as defilement of their women but as a deliberate attempt to humiliate whites as a race. Even at high levels of society, there was some support for mob justice which, through promptness and ferocity, was no doubt a strong deterrent. Rebecca Latimer Felton, who later became a Georgia state senator wrote: “If it needs lynching to protect woman’s dearest possession from the ravening human beasts — then I say lynch; lynch a thousand times a week if necessary.” The Georgian editorialized that “the negro has a monopoly on rape” and that if lynching didn’t stop them perhaps perpetrators should be surgically mutilated.

The early part of 1906 saw an effort to clean up the Decatur street “dives,” which many saw as a breeding ground for criminals and rapists. Reporters went along on inspection tours, and the Evening News described the discovery of a picture of a “horribly disgusting combination of a nude white woman with a negro man,” noting that such pictures were “the favorites among the negro frequenters.” (At the time, “nude” meant partially clothed and suggestively posed.) The Georgian wondered about the typical rapist: “Has he been in the habit of looking at the pictures which cover the walls of these low dives of iniquity?”

As was often the case with early race riots, it was reports of assaults on white women that sparked the violence on this occasion, and Prof. Bauerlein describes in detail how events unfolded. On Saturday, September 22, newspapers reported no fewer than three attempted rapes, with special “extra” editions on new developments. By the afternoon, men began to gather on street corners to discuss what should be done, and some beat up a few blacks. Mayor James Woodward, who was in the crowd, climbed onto a box and is reported to have said:

For God’s sake, men, go to your homes quietly and leave this matter in the hands of the law . . . What you may do in a few minutes of recklessness will take Atlanta many years to recover from. I implore you to leave this matter in the hands of the law . . .

The mob was in an ugly mood, and paid no attention to the mayor. A number of whites ran off towards Decatur Street to warn blacks there could be trouble. A crowd soon gathered at the corner of Decatur and Pryor Streets, but firemen set up water cannon to keep it out of the Negro quarter. A man is reported to have jumped onto a box and shouted: “It’s an outrage for men to let a little water scare them. I will lead the crowd right up Decatur Street.”

By 9:30 in the evening there were yet more newspaper “extras” predicting a race riot. Men poured into hardware and pawn shops to buy weapons. Anderson Hardware Company stayed open all night and sold its entire stock of 400 pistols and 100 rifles. The mayor and police chief ran from one end of town to another trying to cool passions, but the crowds only grew. Many men took streetcars in from the suburbs when they heard something was afoot, and by 10:00 p.m. there were an estimated 10,000 white men in the streets.

Rioting began in earnest, and continued through the night. There was some property damage, but the primary objective was to hunt blacks. The mob seems to have killed blacks who showed fight or shouted abuse, but did not generally beat to death those who simply cowered in fear. Most blacks fled, or found protection in the homes and businesses of white employers, and downtown was soon empty of blacks. The mob began to lie in wait for arriving streetcars, and pounced on unsuspecting black passengers. More than one conductor reportedly prevented further violence by pulling a pistol on assailants. Indeed, part of Prof. Bauerlein’s account reads like a tribute to an armed citizenry. Time and again, rioters looking for blacks sheltering in buildings were stopped by white proprietors who produced guns and announced they would shoot any man who stepped inside. Some police officers arrested rioters and saved blacks at considerable danger to themselves, while others let the mob have its way. Prof. Bauerlein notes that the mob was not indiscriminate; it seems not to have attacked women, and little black boys darted unscathed through the crowd, selling yet more “extras.” The death toll is estimated at 16, with perhaps 50 seriously injured.

By Sunday morning, the Fifth Georgia Infantry was on the streets, and the mob had spent its force. Streetcars ran according to schedule, but with extra conductors armed with shotguns. Peace returned to the city, but there were no shoeshine boys or porters at the railway station, and many black cooks, maids, and handymen stayed home.

All of the better element appear to have been outraged by the violence. By Monday, a number of whites were already in court for prosecution, where Judge Nash Broyles called them “a disgrace to Atlanta and the state in which you live.” Charles Hopkins of the Evening News board of directors wrote, “We have boasted of our superiority and we have now sunk to this level — we have shed the blood of our helpless wards.” He spearheaded a drive that raised $3,782 for the victims and their families. A committee of ten city notables issued a declaration saying: “The rioting of last Saturday night is a blot on the good name of the country, and an outrage on our Anglo-Saxon civilization.” The Evening News tried to explain the bloodshed this way: “There were thousands swept along by curiosity and with no intention of crime who added by their mere presence to the ferocity of the mob leaders, who saw these men behind them and imagined themselves supported by an army.” The Northern press was unanimous in condemnation, with the Philadelphia Press calling the riots “the most deplorable exhibition of race ferocity and savagery that this country has seen for many years.”

The police board charged several officers with dereliction of duty, and fired three, suspended two, and reprimanded one. Eventually, riot victims received more than $5,000 in compensation, both public and private. The book does not cite a single person, high or low, who is recorded as expressing the view that “the niggers got what they deserved.”

We find, therefore, another important difference between riots then and now. Today, virtually no one condemns black rioters in the blunt terms they deserve. Instead, black “leaders” point proudly to the savagery as proof of “institutional racism,” while whites fret about how they failed to “reach out” or “do more.” The contrast with white riots of the past could not be more striking. Even in a period of strict segregation, when politicians spoke about the necessarily “inferior position” of blacks, and newspapers discussed colonization, no one countenanced mob violence. No one agonized over the “root causes” of mayhem. No one thought rioters were anything but vicious thugs.

Today, in an era of invasive anti-discrimination laws and racial preferences, of celebrations of Black History Month and M.L. King Day, of constant glorification of diversity and black “culture,” at a time when white-on-black crime is so rare it makes headlines, politicians and commentators compete to see who can invent the most far-fetched excuses for black mobs. In the aftermath of the Cincinnati riots in April — or of any black riot — one would have searched the mainstream press in vain for the words with which whites condemned Atlanta in 1906: “shame,” “ferocity,” “outrage,” “savagery.” Indeed, for most blacks, the Los Angeles violence of 1992 — in which blacks killed ten whites — was not a riot but an “uprising.” Like the anti-white violence in Cincinnati it was a “wake-up call,” an expression of legitimate grievance whites had better redress. Needless to say, Prof. Bauerlein notes none of these contrasts.

Bits of racial history

Like any detailed study, however, Negrophobia turns up fascinating bits of racial history that run counter to current stereotypes of unanimous Southern contempt for the Negro. In setting the scene for the Atlanta riot, Prof. Bauerlein reports that Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman was a stage play before D.W. Griffith turned it into the movie Birth of a Nation. Many Southerners dismissed the play as “race baiting,” and the Chattanooga Daily Times called it a “riot breeder . . . designed to excite rage and race hatred.” It had toured Atlanta not long before the riots, and afterwards Montgomery, Savannah, Macon, and a number of other Southern cities tried to ban performances.

When the movie version came out in 1915, the city of St. Louis and the state of Ohio managed to prohibit it entirely, and children were kept out of screenings in Chicago. The New York Evening Post, along with the presidents of Harvard and the American Bar Association tried to prevent distribution, and Booker T. Washington called for a boycott. Today, “riot breeders” of a different kind — movies like Mississippi Burning, Malcolm X, and Amistad — face not the slightest resistance.

Negrophobia also gives interesting accounts of the career of Populist Tom Watson, of the struggle between the followers of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, and of the racial undercurrents of the 1906 governor’s race in Georgia. Whatever its ideological slant, there is much to be learned from any serious history that relies as heavily on primary sources as this one.