Where Does the Left Go Now?

Chris Roberts, American Renaissance, April 17, 2020

I follow the “anti-anti-white Left,” a group of mostly Marxist journalists and intellectuals who reject the “anti-racist” positions popular in the Democrat Party and academia. This group supported Senator Bernie Sanders’ insurgent presidential runs, and now that Joe Biden is all but officially the Democrat nominee, it has an unclear future. I was interested in hearing from someone in this group about what they think will come next within the Left, and Benjamin Studebaker agreed to answer my questions. He is working on a PhD at Cambridge, and until recently cohosted the interesting podcast “What’s Left,” with Aimee Terese.

Benjamin Studebaker (Image via Facebook)

Benjamin Studebaker’s Disclaimer: I judge people by what they do to and for other people — by their social roles and relationships — not by their self-conceptions. I believe all identity categories — including race — obscure those roles and relationships. In my view, liberal capitalism indoctrinates people to identify with cultural categories as a means of concealing its exploitative character and preventing its subjects from uniting to challenge it.

Chris Roberts: Since Super Tuesday, the big question for me is, “What will all the energy behind Senator Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaigns get funneled into? What will his supporters do?” The answer is important because Sen. Sanders got so many people interested in politics for the first time, and was the preferred candidate of Hispanics, Asians (America’s two fastest growing racial groups), and young people. What do you think comes next?

Benjamin Studebaker: I see three main possibilities here. First, Sanders supporters could continue to fight to capture the Democratic Party, placing their hopes with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the squad. I doubt these people can get the job done — Ocasio-Cortez seems increasingly reluctant to support Sanders’ insurgent methods. I think it’s more likely that Ocasio-Cortez will try to play the role that was, until recently, played by Elizabeth Warren, acting as an intermediary between disenfranchised progressive voters and the Democratic Party. The function of this kind of Democrat is to shepherd these progressives back to mainstream Democrats, maintaining the status quo by performing radicalism in public.

Second, Sanders supporters could re-align with the Republican Party. Donald Trump has been attempting to reach out to them, and if he were to do something dramatic — like come out for Medicare-For-All — a significant number of Sanders supporters could realign. I doubt any offer would be genuine, but that might not matter. The Democratic Party has moved very far to the right on economic issues and has treated Sanders supporters very badly, and Republicans could get many to flip if they’re willing to at least give the appearance of putting money on the table for Sanders’ signature program. Trump himself has a history of expressing interest in Medicare-For-All, and would be better placed to sell it than most.

The third option is disengagement and protest voting — in which Sanders supporters stay home, write-in for Sanders, or vote for the Greens. Enough of them will do this to prevent Biden from winning, in almost any case. But it’s possible that many of them might abandon national politics on a more permanent basis, if both parties continue to refuse to align with the Sanders platform. Many will shift their focus to local politics, attempting to build up through city councils. The two parties are less attentive to the ideology of their candidates at the local level. It’s their soft underbelly.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez at the Women’s March. (Credit Image: Dimitri Rodriguez / Wikimedia)

CR: At American Renaissance, we think Sen. Sanders did worse with white voters — but better with non-whites — in 2020 than in 2016 because of his about-face on immigration, his pandering to “people of color,” and his use of non-white surrogates (e.g. most of “the Squad”). Do you think that is the case? Will future Leftist candidates find a better way to bring minorities into their camp without losing an equal or greater number of whites, or will this zero sum game of racialized politics spell trouble for decades to come?

BS: I like to say that the 2020 Sanders campaign was much more “McGovernite” than the 2016 campaign. In 1972, George McGovern tried to please college-educated Democratic voters by taking very liberal positions on social issues and by adopting a very dovish foreign policy. At the same time, he was more hostile to the unions than previous Democratic nominees, adopting more right-wing positions on economic issues. This pushed working class, blue-collar Democrats into the Nixon camp. At the same time, the “Rockefeller Republicans” — the socially liberal, but economically conservative Republicans who had backed Nelson Rockefeller in 1968 — began migrating to the Democratic Party. This included people like Hillary Clinton, who attended the 1968 Republican convention to support Rockefeller against Nixon.

This “McGovernite realignment” has grown stronger over time, causing the Democratic Party to rely ever more heavily on college-educated voters who are socially liberal but don’t really care about the ordinary American’s economic well-being. Sanders tried to reverse the McGovernite realignment in 2016 by re-focusing on the economy, but the Democratic establishment accused him of being insufficiently liberal on social issues. I don’t think this was the main reason he lost — Hillary Clinton had a very effective, well-oiled patronage network that was very difficult to overcome in a two-way race. Sanders began 2016 as a protest candidate, and was working with a deeply inferior network. But there was a chunk of young professionals in the Sanders movement who believed he could get through the primaries if he began playing up liberal social-issue positions, and then swing back toward the economic issues in the general election. The 2020 primary campaign was largely led by people with this perspective, and the result was a more conventional Democratic campaign that played up identity. There was much less talk of “the 99 percent” versus “the 1 percent” and much more talk of a “multi-racial working class.” The decision to emphasize race was divisive and alienating, especially to older Democrats who did not go to college and were already skeptical about Sanders’ electability. I don’t think it appealed to many people, apart from the young graduates and professionals who dominate left-wing spaces.

The McGovernite realignment is very difficult to reverse, because the realignment has changed the composition of the Democratic Party’s base. Democratic primary voters are older and more affluent. Many of them are already on Medicare. The unions have much less prominence in the party. The McGovernite realignment has, however, also changed the composition of the Republican Party’s base. There are a lot of workers in the Republican Party now, and the Republican establishment does not use race and gender identity as means of policing out politicians who are hostile to it. Republicans are more skeptical of mainstream media, and the Republican primary system is also much more open to insurgents — there are no superdelegates, and the states are winner-take-all. The Left might find traction in places it doesn’t expect, if it’s willing to think outside the box and talk to workers who are more traditional, more spiritual.

George McGovern speaking on the campaign trail in 1972. (Credit Image: Kheel Center / Wikimedia)

CR: The most famous passage of Hunter S. Thompson’s 1971 book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was about the receding “wave” of 1960s counter-culture:

Strange memories on this nervous night in Las Vegas. Five years later? Six? It seems like a lifetime, or at least a Main Era — the kind of peak that never comes again. San Francisco in the middle sixties was a very special time and place to be a part of. Maybe it meant something. Maybe not, in the long run . . . but no explanation, no mix of words or music or memories can touch that sense of knowing that you were there and alive in that corner of time and the world. . . Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting — on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave. . . . So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark — that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.

Might America’s “socialist surge” have similarly crested and receded? That certainly happened with the “libertarian moment.” It was a new political force backed by energetic young outsiders that broke into the mainstream, and suddenly one day it seemed to have all but disappeared.

BS: I don’t think the 1960s went away. I think it produced the McGovernite realignment, and that realignment pushed the Democratic Party very far to the right on the economy while liberalizing it on social issues. This isn’t the change many in the ’60s were hoping for, but it is a big change. I don’t think the libertarian movement went away either — I think there is a lot of the right-wing libertarian movement in the contemporary Left. Left anarchists and libertarian socialists share right-wing libertarianism’s hyper-individualism. Both prioritize the individual’s quest for self-actualization over collective goals which require the individual to accept a role in institutions and power structures.

Identity is a very individualist way of understanding one’s place in the world. Identity is all about demanding recognition — it’s all about making people see you the way you see yourself. The libertarians were right to identify an appetite for individualism, but they thought young people wanted to be left alone. They don’t want to be left alone; they want to be seen. This individualism prevents the Left from truly escaping liberalism. Liberalism is all about the individual.

For liberals, individuals precede society, and therefore society has a duty to represent the individual, to reflect the individual’s essence back at them. When liberals talk about groups — nations, races, whatever it might be — they simply substitute the group for the individual. The nation or the race is framed as preceding society, and therefore society has a duty to represent the nation or the race and reflect the cultural content of the nation or the race back. True collectivism forces us to acknowledge that individuals and groups are constructed by society, that we are not special, that we are not entitled to special recognition. The Left is deeply alienated from this truth, and the same individualism that animated right-wing libertarianism is driving that alienation.

Image via Crizzle Buttons

CR: Am I a biased “wingnut” for thinking that just as the collapse of the Students for a Democratic Society led to radical terrorist groups such as the Weather Underground, that some fervent backers of Sen. Sanders will become so disillusioned with democracy that they create similar violent groups? Am I foolishly optimistic for thinking some burned out “BernieBros” will come over to the style of thinking found on AmRen and VDARE?

BS: It is relatively easy for people to jump from one mass movement or radical movement to another. It’s much harder for people who are content with the status quo to become frustrated. The Sanders campaign tried to reach out to Clinton voters. Clinton voters were content with the way things were — they aren’t critical of the system and it’s not easy to change that. People who are frustrated feel a pressing need for a solution, and will more easily flip from one solution to another. That said, the United States is generally less violent than it used to be. Rates of violent crime are much lower than they were in the ’60s and ’70s, and there is much less political violence than there used to be. The population is much older, on average, and older populations tend to be much less interested in revolutionary activity. Even on campuses, most activists play it safe and avoid engaging in activity that is likely to get them arrested — they fear a criminal record would follow them around online and prevent them from getting jobs. I think some amount of re-alignment is likely, but it will largely take place within electoral movements.

Journalist Cassandra Fairbanks, one of the more prominent examples of a Bernie Sanders supporter who went on to back Donald Trump. (Credit Image: Info Wars via New York Daily News)

CR: One of the big reasons why Sen. Sanders failed to ever win the Democrat nomination for President was because of his abysmal levels of support from black voters. Why don’t black voters support him? And why did the radical blacks who did support him (e.g. Keith Ellison, Cornel West, DeRay Mckesson) fail to convince very many of the people they claim to represent to do the same?

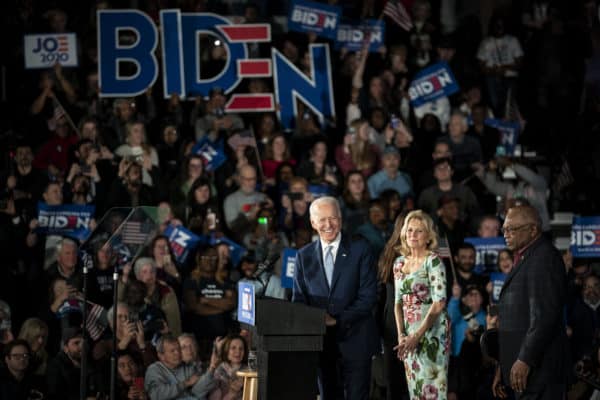

BS: The Sanders campaign was most attractive to downwardly mobile populations — the young, and recent college graduates who found their degrees did not guarantee the job security they anticipated. These people aren’t doing as well as their parents and they are frustrated and demand an explanation and a solution. The campaign was less attractive to voters who were born into poverty, especially older voters who were born poor and have been poor for a long time. They expect very little from the system and prefer electable Democrats who will simply protect them from the Republicans. The downwardly mobile are pretty literate and pretty educated, and they get voting signals from left media. Many people who were born poor are taking their signals from the local politicians and religious figures they know personally. These local leaders are heavily embedded in the Democratic Party’s patronage machine and are much more likely to support establishment Democrats. In South Carolina, Jim Clyburn’s support for Biden was especially decisive.

February 29, 2020, Columbia, South Carolina: Joe Biden speaks, as he is joined by his wife, Dr. Jill Biden, daughter, Ashley Biden, and House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn (D-S.C.), at the University of South Carolina after being declared the winner in the South Carolina Democratic Primary. (Credit Image: © Al Drago / CNP via ZUMA Wire)

Jared Taylor: Race relations have been bad in our country since 1619. Some say they are getting worse. Why do you have hope for a happy resolution of the race problem? Does not the social solidarity of nations such as Hungary, Estonia, Korea, and Japan suggest that we should give up the attempt to build a multiracial society and try to separate in the most humane way possible?

BS: For most of human history, politics has been built around shared political status rather than identity. In the Roman Empire, citizenship was a reciprocal arrangement. Citizens recognized Roman law, and in return Roman law recognized their status as citizens and the legal rights to which Roman citizens were entitled. The Romans were indifferent to an individual’s identity or cultural content, provided that identity and culture did not become an excuse for violating Roman law.

The word in Latin for “citizen” is “civis,” the root word for “civilization” and “civility,” for being “civil.” We can be civil with people who are different from us in all sorts of ways, if we can trust them to follow the law and we can trust the law to prohibit our fellow citizens from exploiting us. For most of Roman history, the Romans did not give citizenship to people who were being heavily exploited, like the slaves. The slaves were not expected to follow the law — they were held by force.

Today, we give citizenship to everybody, including many people who are stuck in roles in which they are exploited. Our legal system does a poor job of protecting citizens from exploitation, and our citizens don’t trust it. The distinction between “citizen” and “non-citizen” holds much less meaning. Because we don’t trust the collective, we relate to it as distinct individuals rather than as members, and we try to protect ourselves by retreating into our identities.

I don’t believe we can or should revoke citizenship from those who hold it. Instead, we should act politically to free our citizens from exploitation, so that our political system becomes worthy of their respect and capable of ensuring they obey the law. Ending exploitation is extremely difficult — slavery and its derivatives have been with us for thousands of years. But I believe technology will eventually make it possible to dispense with wage labor, if a well-organized Left is ready to take advantage of that situation and make it happen. When all citizens have economic rights, they won’t have to use the political system to rob each other. They can be part of it instead of subject to it.

The Smithsonian National Museum of American History was the setting for a naturalization ceremony, during which 14 people received their United States citizenship, on Flag Day, June 14, 2019 in Washington D.C. (Credit Image: © Jeff Malet / Newscom via ZUMA Press)

CR: Something white advocates often make much of is the bitter irony that while we are constantly deplatformed from social media, payment processors, and private services (e.g. Uber, AirBnB), anti-capitalist leftists are left largely undisturbed by the large companies whose destruction they openly support. While there are certainly exceptions, instead of going over them and debating how relevant each is, what do you think explains the overall pattern of difference in how corporations treat racial dissidents and socialist dissidents? Shouldn’t capitalists, who hold profit as their highest ideal, feel more threatened by supporters of the Democratic Socialists of America than AmRen readers? Do you suspect this will change in the coming years? Will Patreon eventually start deplatforming Marxist podcasts? Will credit card companies stop letting payments to Jacobin magazine go through?

BS: Corporations deplatform to protect their bottom lines. While the Left is ideologically hostile to corporations, it usually does not pose any immediate political threat to them. What’s more, deplatforming them tends to generate a negative response from media, feeding hostility to corporations. By letting leftists talk on their platforms, corporations avoid negative press and usually risk very little.

After Sanders’ 2016 run, there was more concern about leftists on media platforms. But it still would have generated negative press to deplatform them for being “leftist.” Instead other justifications had to be invented. Some were accused of being Russian infiltrators. Some were implicated by #MeToo. Some were accused of having latent fascist sympathies, of being “Strasserites.” Playing identity politics became a way of avoiding these accusations — but this made the left more McGovernite, weakening its electoral appeal, and that suited the elite just fine.

People associated with the far-right do not threaten corporations’ bottom lines, and corporations get a lot of negative press when they permit these people on their platforms. It is much more acceptable to cancel someone explicitly for being far-right, so much so that “Strasserite” became a means of cancelling leftists. Most people and firms feel they have nothing to gain from platforming the far-right and much to lose. Even participating in a far-right platform is often enough for you to be accused of legitimizing the far-right. Many liberals today think that even FOX News counts as far-right, for these purposes, and objected to Bernie Sanders’ participation in FOX’s town hall. They think Trump is a fascist and a threat to democracy. If you think the far-right is an immediate, pressing threat, you push to deplatform it.

I think Trump is just another liberal with a nationalist veneer. He supports the same liberal international system that Clinton and Biden support, but he is good at pretending he opposes it, and that has cathartic value for people who are frustrated with liberalism. But it doesn’t get you healthcare and it doesn’t stop the rent from going up. And it certainly doesn’t get us out of this international trade system that forces countries to compete with each other to attract jobs and investment, pushing down wages, taxes, and regulations, and public service provision. Liberals think the far-right wants to kill them, that it is threatening their lives. Liberals think the Left wants to give everybody healthcare. The Left doesn’t scare the liberals in the same way, and if the Left continues to be poorly organized it won’t develop into something that does.

CR: What do you think caused your frequent collaborator, Aimee Terese, to get booted off Twitter, and your (until-recently) podcast “What’s Left” to have its account suspended?

BS: We know that Aimee was kicked off Twitter for tweeting that Elizabeth Warren “needs to be beaten.” We have that on record from Twitter. Aimee was using “beaten” to mean “defeated in an election,” but this was misread (and I think it’s not much of a stretch to suggest it was probably deliberately misread) to mean “physically beaten.” We know that the tweet was part of a thread that was a reply to the Warren campaign’s official account. That doesn’t mean it was the Warren campaign itself which pushed for the ban, but we think it’s likely that it was. “What’s Left” aggressively went after Warren consistently for months. We considered her an existential threat to Sanders from the get-go. They had a lot of reason to hate Aimee.

I don’t know the cause of the suspension of the “What’s Left” account — that was during my month away from the pod, shortly before I left. Aimee was frequently accused of being Strasserite when she was on Twitter. There was never any truth in any of this. She’s a Marxist. But most Americans are never taught Marxism and don’t know what it is. That includes many people on the Left — most of the contemporary American Left is more anarchist than Marxist, and its anarchism is heavily influenced by liberalism.

CR: You and other members of what I call the “anti-anti-white Left” are largely against “woke culture,” “cancel culture,” “performative sensitivity,” and the rest of it. Unfortunately, the dramatic end of Sen. Sanders’ campaign is a blow to this wing of the Left. How do you see anti-racist theatrics evolving in the next few years? Could it intensify? Do you think it will ever “overreach” so much that it finally collapses under the enormous weight of its own absurdities? What social or political force do you think most threatens it?

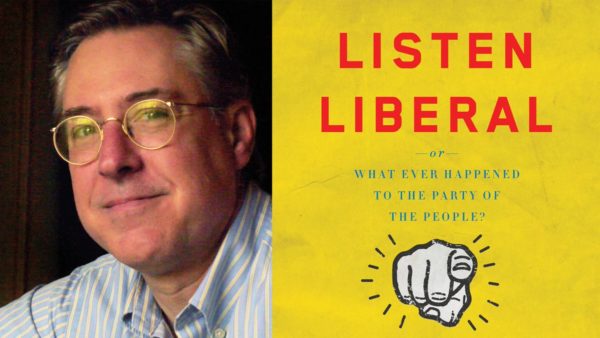

BS: The main division within the Left is between the college-educated, professional class Left and the working class it purports to serve. Frantz Fanon was able to pinpoint this in The Wretched of the Earth, and Thomas Frank has been able to get at it more recently in Listen Liberal. The division manifests differently at different moments. For much of the past decade, the professional class has liked to signal its superiority to the workers by emphasizing its superior social issue positions. This alienates the workers, but the professionals either fail to see this or blame the workers for failing to educate themselves. It could continue, but I could also see it changing. Aimee [Terese] often liked to suggest that climate change could play this role — in Europe, I’d argue it already does to a significant degree. It’s easy for professionals to virtue signal on climate change and to condemn workers for being insufficiently green. The more they do this, the more climate change becomes another culture war issue, another thing that is polarized. It makes it harder to do anything about climate change, politically, but the professionals are either unaware of this or blame the workers.

Recently, coronavirus has jumped in to take this spot. The professionals stay home and socially distance, virtue signaling their willingness to protect other people from the virus. The workers continue to go to work and continue to get the virus, and the contraction of the economy subjects more and more of them to unemployment. The professionals act like they love the “essential workers” — clapping for them, and so on. But this appreciation is itself another form of virtue signaling, and they are the ones allowing the poor to take the brunt of the economic beating. They are also the ones mocking religious people for wanting to continue to go to church, and they are the ones calling the police on workers they see outdoors hanging out with friends.

The professionals will always invent new forms of language and new forms of moral behavior that they are privy to and the workers are not. They will always hold the workers in contempt for failing to keep up. And the workers will resent them for this, and they will be alienated from movements the professionals have hijacked. This alienation has pushed so many workers to the right, but the professionals can’t see it. They think they are fighting the Right when they are fueling it. This will last as long as the professionals and workers are trying to do politics together. The workers need their own left movement, one which accepts them as they are and makes the most of what they have to offer. But they don’t have the resources or organization necessary to make such a movement, and every time professionals try to help them the movement ends up overrun with professionals. The professionals can’t make a movement for the workers. They are too individualist, they need their organizations to reflect their own cultural tastes, even though this guarantees defeat.

CR: American Renaissance readers are not interested in books that claim race is a fiction, or that lionize the plight of immigrants or non-white pressure groups. However, could you recommend one book that might expand or challenge the way we typically think about class, economics, and/or the Left?

BS: If I had to pick one, it’s Listen Liberal by Thomas Frank. It’s a smooth read — Frank’s style is terrific. There’s no better place to go for a readable left-wing account of what’s happened to American politics over the past 50 years. There’s no stupid stuff in it, I promise.

CR: Any final thoughts on the upcoming presidential election, the future of the Democrat Party, or how America will change in the next one or two decades?

BS: The biggest problem with the world today is that we have economic integration without political integration. If we raise taxes or wages, rich people can take their money somewhere else. Rich people have no loyalty to us on the basis of shared identity. They want us to think they do, but they don’t. Their goal is to make as much money as possible. That means keeping their expenses as low as possible. If you are an employee, you are an expense. If someone in China is cheaper, they will hire someone in China, not because they love the Chinese or the Asians but because they don’t care about anything except their rate of return. They don’t care who gets the crumbs, just as long as they ensure they leave very few behind. They aren’t part of any collective project, they don’t view themselves as citizens of anything, and they have no loyalty to anyone.

Capitalism makes them what they are; it has incentivized them to become what they are from the moment they were born. We aren’t going to be able to get out from under them until we can stop them from playing our states off each other. That means either we have to put a stop to the movement of capital or we have to construct global or international political institutions that can govern its movement. As Americans, we are lucky. Our state is the most powerful state in the world, and if we come together to make it change the international economic system, it might really have the power to do it. We reshaped the global economic order in the 1940s and again in the ’80s — if we do it again, we can secure the fundamental economic rights our leaders have always refused to acknowledge. Or we can continue to let them divide us over identity and culture, and get more remixes of the same old thing. Eventually, climate change and automation will come — and if they arrive when we’re divided, we won’t be able to cope.