Why Do We Vote as We Do?

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, October 24, 2014

Jason Weeden and Robert Kurzban, The Hidden Agenda of the Political Mind: How Self-Interest Shapes our Opinions and Why We Won’t Admit it, Princeton University Press, 2014, 363 pp.

Why do we vote the way we do? The answer is obvious: We vote for politicians who promise to do what’s in our interests. Surprisingly, the obvious is not obvious to political scientists, many of whom think that we vote according to principles or because of party or religious affiliation. The Hidden Agenda of the Political Mind claims to strip away these pretenses and lay bare the self-interested motives of voters. The authors do have some interesting insights, but despite their claims of ruthless objectivity they have obvious and unforgivable blind spots — in exactly the areas we would expect.

Personal interests

Jason Weeden and Robert Kurzban, both academics, have a view of human nature that is based on recent work by such authors as Jonathan Haidt. They write that because “human minds are designed for spin,” most of our desires are unconscious, and the reasons we give for our actions are “socially attractive veneers.” There is much to say for this view; motives — even our own — can be murky. People often claim high motives for themselves and low ones for others: “I want to be a lawyer so I can work for social justice; my law-school classmates just want to get rich.”

Politics, however, is usually much more straightforward. It is an attempt to rearrange America in ways that benefit specific groups. Blacks want more handouts and Jews want to stop school prayer. Rich people want lower taxes and white people want less immigration. Messrs. Weeden and Kurzban therefore go too far when they write that “in our view all sides typically seek to advance their interests and are hypocritical in the way they present their views.” They even write that it is unacceptable “to talk truthfully about the fact that politicians try to appeal to voters’ interests,” but this lets them claim that their own analysis is a brave assault on taboos.

What is useful in this book is the recognition that voter interests reliably reflect specific demographic traits such as wealth, brains, education, sex, race, erotic orientation, religious fervor, and immigrant status, and that different combinations of these traits lead to different voter preferences that don’t fall neatly into conservative/liberal categories.

This is why the two major parties are both uneasy coalitions. Unlike parliamentary systems in which voters may have a dozen parties to choose from, Americans have to pick from just two. This means a voter has to dig through a mishmash of positions to decide whether the Democrats or the Republicans even roughly represent his overall interests.

It is not a mistake to think of these two coalitions as generally to the left and to the right of center, but the authors argue that there are not that many Americans whose opinions are consistently to the left or the right. Many commentators think that if you know someone’s position on one controversial issue — abortion, for example — you know his positions on everything else, from racial preferences to military spending. However, the authors point out that this kind of consistency is true only for upscale white people. Since most commentators fit this profile and since they don’t know any other kind of people, they think everyone is predictably and consistently liberal/Democratic or conservative/Republican.

Not so, say Messrs. Weeden and Kurzban, and the further down the economic scale you go, the more inconsistent Americans are. A famous example is black resistance to homosexual marriage. White Democrats, who think of blacks as reliable allies in the liberal cause, don’t actually understand blacks. Blacks vote Democrat because they want more handouts and racial preferences; not because they are “liberal” in any principled way.

At least blacks have a party that looks out for them; lower-class whites don’t. As the authors point out, Republicans attract these people because the party is only lukewarm on immigration and race preferences, but Republicans also want to cut back on handouts, which some lower-class whites want. Democrats are for handouts but fawn over non-whites and immigrants.

The authors admit that given this choice it is no wonder many lower-class whites don’t vote. Their mix of liberal/conservative views would draw them to a populist/nationalist party such as the Front National in France, but our rigid two-party system leaves them with nothing.

Sex

The authors offer an interesting analysis of how personal views about sex often drive political positions on “social” issues such as abortion, school prayer, homosexual marriage, and drug laws. A lot of Americans want to spend 10 to 15 years having recreational sex with many partners before they settle down and have children. They want society to accept fornication, and they certainly don’t want to be forced to have unwanted children. They therefore want easy access to contraceptives, and a backstop for when contraception fails: abortion. People who live like this also want tolerance for homosexuals because that usually comes with tolerance for fornication. They also favor loose laws on booze and marijuana because they make sex more likely.

A lot of other Americans don’t like any of this. They are family oriented, and believe sex outside of marriage undermines families. The authors concede that they are right about that: The more sex partners people have before they marry, the more likely they are to divorce, whereas when two virgins marry their chances of divorce are a very low 15 percent. Sexually conservative people don’t want to lift the sanctions on fornication or adultery. A girl asking her boyfriend to wait until they are married may be asking the impossible if there are plenty of other girls who are willing to do it right now. Also, people who build their lives on the ideal of stable marriage fear that a social atmosphere of sport sex threatens that ideal. They want to make promiscuity less likely by making it more risky — by banning abortion and making contraceptives hard to get.

The anti-fornication crowd also tends to be religious. According to Messrs. Weeden and Kurzban, there is a very strong negative correlation between church going and number of sex partners. They write that churches can almost be seen as support groups for people who practice conservative, family-oriented sex. That is why views on sex are closely tied to views on prayer in school.

It is common to think that most people absorb their parents’ religion, and that religion determines views on sex. The authors suggest otherwise. They are aware of the extent to which genes influence this kind of behavior, and even cite longitudinal studies suggesting that it doesn’t make much difference how you are reared; promiscuous people will leave the church, and people who are family-oriented will find a church even if they weren’t reared in one.

The authors argue that both sides of the debate hide their real motives. Pro-abortion people don’t say, “I want to screw around until I’m 30 and I’ll be damned if I’m going to have a child just because I knocked up a drunk stranger.” Instead, they invent a “right to privacy” and prate about “a woman’s right to control her body.” They throw away their privacy on Facebook, and are perfectly happy for a woman to give up control of her body in the name of mandatory seat-belt laws or health insurance, or bans on smoking and giant soft drinks.

The other side is dishonest, too. It claims that the Bible condemns abortion, whereas the Bible never mentions it. It also claims life begins at conception, but it also often permits abortion in cases of rape or incest. If life begins at conception how do you justify killing a fetus even if there was rape or incest? Presumably, no one would kill a two-year-old just because his father was a rapist. Even though people routinely vote their interests, they may hide their interests.

Many political scientists reportedly think that party affiliation is like religion: People stumble into it early in life, and then mold their politics to the party line. One does hear of people who are firm Democrats because their parents were firm Democrats, but Messrs. Weeden and Kurzban think that is unusual. People usually start with an issue about which they feel passionately — whether it is abortion or tax rates — and start voting for candidates that promise what they want. If they then get active in party politics in any way, they start spending time with people who support the party for other reasons, and may then adjust their less-strongly-held views to match those of their friends. Their initial partisan impulse comes from conviction, and that conviction is based on personal interests.

Other policies

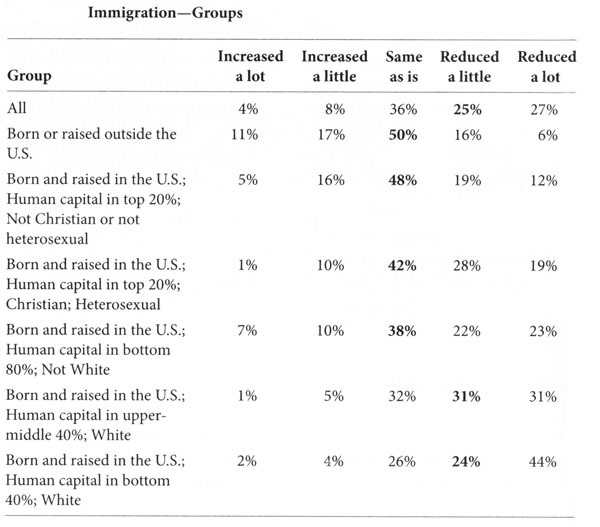

Let us see how demographic characteristics tilt people’s interests on other political questions. Here is a table that reflects what different groups think about immigration. Except for the “All” category, which includes everyone, the groups are ranked, top to bottom, according to how likely they are to want more immigration. It’s worth looking carefully at the group descriptions to see how the authors have divided up the population. By “human capital” they mean brains and education. The bold number reflects the median view of each group.

Not surprisingly, immigrants like immigration, but even for them the median opinion is to leave current levels unchanged. The group that thinks most like immigrants is brainy, educated non-Christians and homosexuals. The authors, who refer to this group as “heathens,” note that Jews, Buddhists, Hindus, and homosexuals — especially when they have lots of “human capital” — think so similarly that it makes sense to lump them together.

The other groups show that whites, in general, want less immigration, and that whites with the least education and brains want the least. This makes sense. Upscale whites, even if they tilt towards immigration control, might want to hire cheap Mexicans, whereas working-class whites have both racial and economic reasons to keep Mexicans out.

The authors note that the country as a whole — the All category — tilts pretty strongly towards cutting immigration, but the country doesn’t get what it wants. Minorities flout the majority will.

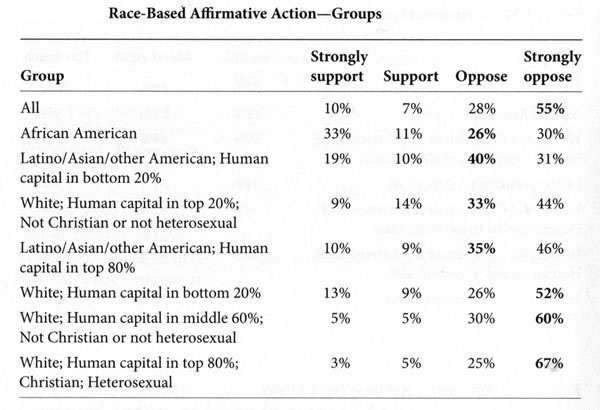

Here is another example of the same thing. This table shows what different groups think about racial preferences for non-whites. Here, the All category’s median opinion is “strongly oppose,” with only 17 percent of Americans showing any support at all. Blacks like race preferences more than anyone else, but even for them, a majority is against them. Even middle-class heathens (the group second from the bottom) are overwhelmingly against race preferences, despite being liberal on many other questions.

This means that on the two issues most important to whites — immigration and race preferences — policy is squarely against their interests. The authors concede that laws on abortion and school prayer also go against majority interests. Why? The authors pat themselves on the back for laying bare the naked interests of Americans and explaining how interests drive policy. If interests drive policy, why does their vaunted analysis fail on these four important issues, all of which are important to whites?

And why is it that when policy runs counter to majority interests, it always veers off in a liberal direction? Why are there no policies that are more conservative than the majority wants? The authors — who cheerfully admit to being heathens — say it is because elites make policy, and elites, whether Democrat or Republican, tilt Left. There is some truth in this, but when it comes to immigration and race preferences, the majority will is trampled mainly because whites are forbidden to organize along racial lines the way everyone else does. Messrs. Weeden and Kurzban fail to see that.

What they do see are ghosts of policies that have been dead for 70 years. This book claims that lower-class Christian heterosexual whites “hold group-based issue preferences that seek to help people in their own groups and hold back people not in their own group.” This is understandable because “people with less human capital do better when advantages are given to their own groups and other groups are held back.” That’s right: Drooling rednecks are politicking to hold back the darkies. Rednecks vote Republican because the party favors “anti-meritocratic advantage for traditionally dominant groups.”

Messrs. Weeden and Kurzban pass this nonsense off with a straight face and without a scrap of data. They also claim that smart “heathens” like themselves live in constant fear that the white, Christian, heterosexual majority will rise up and write anti-meritocratic rules to keep them down. It would be hard to imagine a more sweeping — but fashionable — set of prejudices.

This is especially shocking in a book that claims to be immune to prejudice and willing to follow the data wherever they lead. It is hard to know whether the authors know they are making things up or are genuinely taken in by their dark fantasies about white people. In either case, it is disappointing that authors who are capable of a subtle analysis of party politics or views on abortion should be guilty of elementary blunders when it comes to race. But it is no surprise.