It’s Race, Stupid

Samuel T. Francis, American Renaissance, January 2001

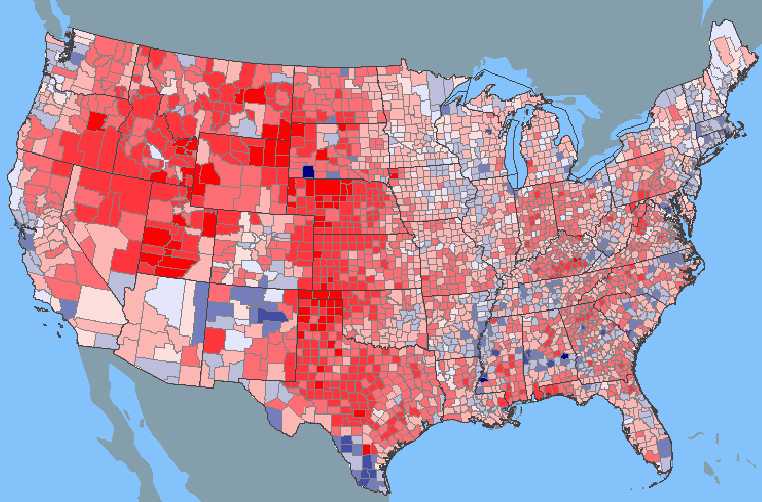

If there is one pattern that emerges from the confused national election of 2000, it is that race and ethnicity are the driving forces in American politics today. An analysis of exit polls confirms that, so far from evolving toward a “color-blind” society in which most citizens are indifferent to racial identity, Americans are voting along clearly defined racial and ethnic lines. These voting patterns strongly suggest, if they do not confirm, that racial consciousness is a major determinant of voting behavior and that political appeals to racial interests and consciousness will continue to play a major role in the politics of the future.

The correlation of racial identity and voting behavior is most clear among blacks, who voted overwhelmingly for Democratic presidential candidate Vice President Al Gore. Black voters, making up some 10 percent of the electorate, supported Mr. Gore by 90 percent. While 85 percent of black men supported Mr. Gore, his support among black women was even larger — a huge 94 percent. Nationally, about 19 percent — nearly one in five — of Gore’s votes came from blacks.

Correspondingly, the level of black support for the Republican presidential candidate, Texas Gov. George W. Bush, was strikingly low — only eight percent. Black men went for Bush by 12 percent, but only six percent of black women supported him. While black voters have historically been overwhelmingly Democratic since the 1960s, Mr. Bush’s black support, analyst DeWayne Wickham reported in USA Today, was “the lowest total garnered by any Republican presidential candidate since Barry Goldwater managed to win just 6 percent of the African-American vote in 1964,” and was lower even than the nine percent Ronald Reagan won in 1984.

One of the main reasons for strong black support for Mr. Gore is that both his campaign as well as its black supporters in the NAACP and similar racial activist lobbies worked hard to increase black turnout and to incite racial fears. Thus, in a speech at Wesley Center AME Zion Church in Pittsburgh, Pa., on Nov. 4, Mr. Gore told the black church audience, “When my opponent, Gov. Bush, says that he will appoint strict constructionists to the Supreme Court, I often think of the strictly constructionist meaning that was applied when the Constitution was written and how some people were considered three-fifths of a human being.”

The vice president was referring to the section of the Constitution (Article I, §2) that provided that slaves would be counted as three-fifths of a person for purposes of congressional apportionment. This section, inserted into the Constitution against the wishes and interests of Southern slave owners to diminish their power in Congress, was never a result of “construction” of any kind and referred only to slaves, not to free blacks. Mr. Gore’s misrepresentation insinuated that Mr. Bush’s support for “strict constructionism” would lead to the restoration of segregation, if not slavery.

Mr. Gore also told the same audience, “I am taught that good overcomes evil if we choose that outcome,” a passage the Bush campaign understandably interpreted to mean that Mr. Gore as implying Gov. Bush himself was “evil.” If that was his meaning, it was entirely consistent with a television ad sponsored by the NAACP that used the voice of the daughter of black murder victim James Byrd, Jr., slain in Texas in 1998 for apparently racial reasons, and which, as Matthew Rees of the Weekly Standard wrote, “all but blamed Bush for her father’s death at the hands of white racists.” This and similar NAACP-sponsored ads on television and radio accused Bush of indifference to “hate crimes,” opposing new hate crimes legislation for Texas in the wake of the Byrd killing, and opposing federal legislation against “racial profiling.” Most of these ads strongly insinuated that Bush’s positions were driven by racial bigotry. In the congressional elections of 1998, Democrats used similar ads that sought to link Republicans with the arson of black churches. In 2000, the NAACP spent some $12 million through its National Voters Fund in a campaign to register black voters and get them to the polls.

The result of this kind of direct appeal to racial fears and animosities was not only the 90 percent black support for Gore but also a record black voter turnout in critical swing states. While the national black turnout remained about the same in 2000 as in 1996 (about 10 percent of all voters), “black turnout increased more dramatically in states targeted by the NAACP, labor unions, and the Democratic Party,” the Washington Post explained. The Wall Street Journal reported that in Florida “[black] turnout surged by 50 percent from four years ago, giving blacks clout beyond their share of the voting-age population,” and DeWayne Wickham in USA Today attributed the forced vote recount in Florida to the massive black support for Gore (93 percent) in that state. Some 29 percent of Gore’s votes in Florida came from black voters. Political scientist David Bositis told the Journal that “Black-voter turnout appears to be a significant factor this year. In Michigan, Delaware, Florida, and Pennsylvania, black voter turnout was absolutely critical” to Gore’s final vote counts.

Much the same racial-ethnic pattern is apparent in the strong Hispanic support for Mr. Gore, despite concerted efforts by Mr. Bush and the GOP to court the Hispanic vote. Mr. Bush did make some gains among Hispanic voters, winning 31 percent of their support nationally as compared to Bob Dole’s poor showing of only 21 percent in 1996. But Hispanics, who make up some 7 percent of the electorate nationally, went for Mr. Gore in 2000 by a huge 67 percent — if not as large as his black support, nevertheless a return of landslide proportions. In California, Hispanic turnout increased by about 20 percent over 1996, while nationally Hispanic turnout rose by about 2 million voters in 1996 to about 7 million. It should be noted that Green Party candidate Ralph Nader received one percent of the black vote, two percent of the Hispanic vote, and four percent of the Asian vote; Mr. Gore’s support among all these groups would undoubtedly have been somewhat larger had Mr. Nader not been on the ballot. Moreover, analysis of the Hispanic vote by region suggests that all of Mr. Bush’s rather frenetic courtship of it availed him little.

In an analysis written the day after the election, United Press International correspondent Steve Sailer examined Hispanic voting trends in the four major regions of the United States where Hispanics are concentrated: California, Texas, New York, and Florida. In California, which has the nation’s largest number of Hispanic voters (3 million) and where Hispanics make up 13.4 percent of the electorate, Bush lost the Hispanic vote to Gore by an even larger margin than he lost it nationally — 28 percent to Gore’s 67 percent (the Orange County Register a week after the election reported Bush won only 21 percent of the state’s Hispanics). Yet, in New York, with the third largest concentration of Hispanic voters (8.2 percent of the state electorate), Mr. Bush lost (largely Puerto Rican) Hispanic support even more dramatically, carrying only 18 percent to Mr. Gore’s 80 percent. (Hillary Clinton in her successful race for the U.S. Senate seat from New York won 85 percent of Hispanic votes.)

In his native state of Texas, which has the nation’s second largest Hispanic electorate (19.6 percent), Mr. Bush also did poorly, losing the Hispanic vote to Mr. Gore, 42 percent to 54 percent. This was an improvement over Mr. Bush’s 39 percent Hispanic vote in his re-election for governor in 1998, but it was considerably less than what he and his pro-immigration conservative supporters had expected. In Florida, Mr. Bush actually did win the Hispanic vote, though narrowly. There, where the nation’s fourth largest Hispanic community constitutes 11.9 percent of the electorate, Mr. Sailer reported Mr. Bush winning the Hispanic vote 50 percent to 48 percent.

The Florida Hispanic vote, however, is largely Cuban, and Cubans have historically voted Republican. Democratic presidential candidates have traditionally received only 13 percent to 15 percent of the Florida Cuban vote, though in 1996 Bill Clinton actually won 27 percent of the Cubans. In 2000, unofficial returns showed Mr. Gore won the heavily Cuban Miami area by 39,000 votes, though this was a considerably smaller margin of victory than that of Mr. Clinton in 1996. But in two heavily Cuban precincts, the 510th and the 555th, Mr. Bush won 79 percent and 89 percent respectively. The reason for Mr. Bush’s win among Hispanics in Florida, in most experts’ views, is the Clinton administration’s support for returning Elian Gonzalez to Cuba. As Fox News’ Malcolm Balfour reported, one local voter of Cuban background told him a few days after the vote, “I know hundreds of people who registered to vote just because of that raid on Elian’s relatives’ home. Last time, I voted for the Democrat, Bill Clinton, but no way would I vote Democrat this time around. . . .” Two days before the election, the St. Petersburg Times reported that “as Election Day nears Cuban-American exiles are getting ready to exact their revenge [for Clinton’s policy toward the Gonzalez boy],” even though Mr. Gore himself expressed disagreement with the administration’s policy.

In three of the four major regions of Hispanic concentration in the United States, therefore, George W. Bush lost the Hispanic vote to Al Gore, including in his own state. Even in the only state where he did win a bare majority of Hispanics, his victory was mainly due to a combination of unique traditional Republican loyalties among Cuban voters coupled with ethnic solidarity with the Gonzalez boy and anger at the Clinton administration. Mr. Bush also did poorly with Hispanic voters in other Western and Southwestern states. In Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico, where Hispanics are eight to 35 percent of the electorates, Mr. Bush consistently won only about 30 percent, to about 67 percent for Mr. Gore.

The low Hispanic vote for Mr. Bush was of special significance because of the drift of the Republican Party’s policies toward immigration in the last few years. While GOP presidential candidates from Nixon to Reagan generally won about 30 percent to 35 percent of the Hispanic vote nationally until 1992, GOP candidate Bob Dole in 1996 won only 21 percent. This low figure has been used by many pro-immigration Republicans to argue that the party made a major blunder when in 1994 it and incumbent California Republican Gov. Pete Wilson supported California’s Proposition 187, which would have denied public benefits to illegal immigrants.

For these Republicans, one of the major attractions of George W. Bush as a candidate was his pro-immigration positions and his supposed attractiveness to Hispanics. Throughout the campaign Mr. Bush repeatedly called for more immigration from Latin America, praised its results, and distanced himself from immigration restriction. Last August, Mr. Bush described the effects of immigration in these glowing terms in a speech to a Hispanic audience in Miami:

“America has one national creed, but many accents. We are now one of the largest Spanish-speaking nations in the world. We’re a major source of Latin music, journalism and culture.

“Just go to Miami, or San Antonio, Los Angeles, Chicago or West New York, New Jersey . . . and close your eyes and listen. You could just as easily be in Santo Domingo or Santiago, or San Miguel de Allende.

“For years our nation has debated this change — some have praised it and others have resented it. By nominating me, my party has made a choice to welcome the new America.”

Mr. Bush often campaigned in Spanish and made heavy use of his half-Mexican nephew, George P. Bush, in his campaign appeals to Hispanic voters. His enthusiasts in the conservative press, such as the Washington Times’ Donald Lambro, confidently predicted (in Dec., 1999) that Mr. Bush would win the Hispanic vote. “George W. Bush is winning support from a majority of Hispanic voters,” he wrote and cited “Hispanic officials and grass-roots activists” who said Mr. Bush’s support among Hispanics was “the result of Mr. Bush’s efforts to reach out to Hispanics with a message of inclusiveness and with tax-cut proposals that appeal to business owners and families with children.”

In fact, the whole argument that Republican and conservative support for Proposition 187 and for immigration control had alienated Hispanics from the GOP is open to question. In the first place, strong Republican candidates like Nixon and Reagan could win 30 to 35 percent of the Hispanic vote nationally, while weaker candidates like Gerald Ford in 1976 and George H.W. Bush in 1992 were able to win only smaller shares — well before Proposition 187. Mr. Ford in 1976 won only 24 percent and Mr. Bush in 1992 won only 25 percent of the national Hispanic vote. Mr. Dole’s 21 percent in 1996 is consistent with the performance of a weak Republican candidate. Moreover, Mr. Dole himself publicly repudiated the Republican Party’s platform plank calling for immigration control (drafted by Buchanan forces at the GOP convention) and chose as his running mate the militantly pro-immigration neoconservative Jack Kemp, who had actively opposed Proposition 187 in 1994. Mr. Dole himself had no visible record on immigration issues. Whatever Pete Wilson and California Republicans might have said or done to alienate Hispanic voters in 1994 did not apply to Mr. Dole and Mr. Kemp in 1996 (or cause low Hispanic support for George W. Bush outside of California in 2000). In any case, 23 percent of Hispanic voters in California voted for Prop. 187, suggesting that about a quarter of the Hispanic vote in the state is essentially conservative and is what Republican candidates should normally expect to get.

It is likely that Hispanics vote for Democrats over Republicans simply because, like most low-income groups, they favor liberal candidates over more conservative ones and because Democrats are far more open than Republicans to multiculturalism and the black-Hispanic racial agenda. Nor should Hispanic solidarity with the Democrats be surprising. As a report in the Boston Globe pointed out shortly before the election, “more than 1.7 million resident aliens have become U.S. citizens in the past two years, most of them with an incentive to vote and a lopsided preference for the Democratic Party.” The story quoted one California Democratic activist as saying, “Both parties show up at swearing-in ceremonies to try to register voters. There is a Democratic table and a Republican table. Ours has a lot of business. Theirs is like the Maytag repairman.”

The only people surprised that Hispanics did not flock to Republican banners were the Republicans themselves. All the desperate pandering to minorities Mr. Bush and his “Rainbow Republicans” practiced at the Republican convention and during the campaign does not alter the basic pattern of racial-political solidarity of both blacks and Hispanics.

Other ethnic groups showed similar solidarity in the 2000 election, with Jews voting 79 percent for the Gore-Lieberman ticket (Jewish voters traditionally cast about a third of their support to the Republican nominee, but in the 1992, 1996, and 2000 elections the Republican candidates won only 11 percent, 16 percent, and 19 percent of the Jewish vote respectively). Similarly, Asian voters went for Mr. Gore by a solid (though not overwhelming) 54 percent; in 1992, 55 percent of Asian voters supported George H.W. Bush and in 1996 48 percent supported Mr. Dole and only 44 percent Mr. Clinton. These figures show a steady trend among Asian voters toward the political left during the last decade. Reportedly, about 70 percent of American Indians and about 60 percent of Arab-Americans also voted for Mr. Gore.

The pattern is clear: Non-white voters tend to form increasingly solid blocs that support the Democratic Party’s deference to explicitly racial and anti-white policies. Yet, despite the racially driven politics among non-whites, there is one major racial group in the American electorate that does not vote as a bloc: whites themselves.

In 2000, white men, who compose 39 percent of the electorate, voted for George W. Bush over Al Gore by 60 percent to 35 percent. White women, who make up 43 percent of the electorate, were much more evenly split, with 49 percent voting for Mr. Bush and 48 percent for Mr. Gore. White voters in general, who compose 82 percent of the electorate, voted for Mr. Bush over Mr. Gore by 54 percent to 42 percent.

The table on this page shows that while a majority of white voters usually vote for the Republican candidate, only twice in the eight presidential elections since 1972 — in that year and in 1984 — have they voted together by more than 60 percent and only four times have more than 55 percent of whites voted together for a single candidate. Compare this level of bloc voting to that of blacks (always 80-90 percent) or Hispanics (always 60-75 percent), and it is clear that of the three major racial/ethnic groups in the United States, whites vote much less as a bloc than the two others.

|

Year

|

Republican

|

Democrat

|

3rd Party

|

|

1972

|

Nixon,* 67%

|

McGovern, 31%

|

|

|

1976

|

Ford, 52%

|

Carter,* 47%

|

|

|

1980

|

Reagan,* 56%

|

Carter, 36%

|

Anderson, 7%

|

|

1984

|

Reagan,* 64%

|

Mondale, 35%

|

|

|

1988

|

Bush, Sr.,* 59%

|

Dukakis, 40%

|

|

|

1992

|

Bush, Sr., 40%

|

Clinton,* 39%

|

Perot, 20%

|

|

1996

|

Dole, 46%

|

Clinton,* 43%

|

Perot, 9%

|

|

2000

|

Bush,* 54%

|

Gore, 42%

|

Nader, 3%

|

The percentage of whites who support the Democrats does not usually change significantly from year to year, but by winning 42 percent Mr. Gore did better than most Democratic candidates in the recent past. The 42-43 percent of white votes Messrs. Gore and Clinton won in 1996 and 2000 respectively is more than any Democratic presidential candidate has won since Jimmy Carter in 1976. Correspondingly, Mr. Bush’s 54 percent majority last year, while better than Bob Dole’s and Mr. Bush’s father’s losing performances in the ‘90s, is a distinct decline from the nearly 60 percent average won by Republican nominees in the 1970s and ‘80s.

One major reason for the improvement of the Democratic ticket in winning white votes is the change in political strategies of the two parties in recent years. The Republicans have deliberately neglected their natural political base among white voters in a fruitless pursuit of non-white voters, while the Democrats have not hesitated to appeal to at least key sectors of the white vote even as they also made appeals that were non-white and even anti-white.

Thus, the “Rainbow Republicanism” of the GOP convention and campaign, with minorities conveniently sprinkled in visible spots, Colin Powell’s speech defending affirmative action, the benediction offered by a Muslim, and Mr. Bush’s slogan of “compassionate conservatism” were all consistent with the Republicans’ abandonment of immigration control, their support for Puerto Rican statehood, and their backing away from opposition to affirmative action despite successful state-level ballot measures against it. As black conservative columnist Armstrong Williams wrote, “Gov. Bush pursued African-American connections with more avidity than any Republican candidate of recent memory did. He studded his campaign trail with stops at inner-city schools, churches, welfare offices, and black communities. He filled his commercials with minority faces in an attempt to tell minority voters they were part of his party. He prominently kissed a black baby and could often be seen mingling with Hispanics.”

These tactics were not exclusively the result of Bush’s growing prominence in the party but due also to a widespread belief among party leaders that winning non-white votes is essential to the party’s future. Whereas strong Republican candidates like Nixon and Reagan in the 1970s and 1980s relied on what came to be known as the “Southern strategy” to win high levels of support among white voters, the new Republicans of the 1990s explicitly rejected that strategy.

Thus, GOP pollster Lance Tarrance told the Washington Times in January, 2000, “We have now moved from the Southern strategy we pursued for the last three decades, since Richard Nixon, to a Hispanic strategy for the next three decades.” Similarly, Jim Nicholson, chairman of the Republican National Committee, told the Times, “This party is going after the growing Hispanic vote with TV ads, Hispanic candidate recruitment attempts, campaigns conducted by Spanish-speaking Republicans in Latino communities and an all-out effort to persuade newly naturalized citizens of Hispanic origin to join the Republican Party.” In 1999, Republican state Sen. Jim Brulte of California vowed he would no longer support financial contributions to white, male candidates. “My leadership PAC will give no more money to Anglo males in Republican primaries,” Sen. Brulte said. “Every dollar I can raise is going to nominate Latinos and Asian Americans and women.”

In August, 2000, the Washington Post cited Karl Rove, Bush’s top political strategist, as dismissing the Southern strategy as an “old paradigm” that “past GOP candidates had employed in a calculated bid to polarize the electorate and put together a predominantly white majority.” “People are more attracted today by a positive agenda than by wedge issues,” Rove told the Post. Ralph Reed, the former executive director of the Christian Coalition and now a Republican political consultant, also told the Post, “This is a very different party from the party that sits down on Labor Day and cedes the black vote and cedes the Hispanic vote, and tries to drive its percentage of the white vote over 70 percent to win an election.”

But the actual result of this new strategy is evident from the exit polls of the 2000 election. The strategy failed to attract significant numbers of non-white voters; it failed miserably to win black votes and won only enough Hispanic votes to raise Hispanic support to not quite the traditional level. More significantly, it also failed to attract the large numbers of white voters who are the natural base of the party and who remain essential for the kind of clear-cut, landslide electoral victories won by Mr. Nixon and Mr. Reagan. Mr. Bush was able to win a small majority of white voters, but without the explicit appeals that Mr. Nixon and Mr. Reagan made, he and his party are unable to win larger majorities. Experts like Messrs. Reed and Rove are entirely correct that today’s GOP is a different party from the old one. The old party could win landslide victories through the Southern strategy and by appealing to white voters. The new party can barely win elections at all and managed to lose the popular vote.

As Steve Sailer has shown in an interesting set of calculations on immigration expert Peter Brimelow’s VDARE.com website, if Mr. Bush had cultivated his natural base and increased his percentage of the white vote by only a few percent he would have won overwhelmingly. If, instead of 54 percent he had won 57 percent (not hard to imagine, since his father won 59 percent in 1988), he would have won an electoral college landslide of 367 to 171. What if winning another three percent of the white vote had required appeals that scared away so many non-whites their support dropped by more than a third, from 21 percent to 13 percent? Mr. Bush still would have won comfortably, with 310 electoral votes to 228. Incredible as it seems, if by increasing his percentage of the white vote by those crucial three percentage points the number of non-white supporters had dropped to zero, Mr. Bush would still have ended up with a tie in the electoral college. As Mr. Sailer points out, no less than 92 percent of Mr. Bush’s votes came from whites; it is folly for Republicans to go on a snipe hunt for non-white votes if by doing so they risk losing even a tiny percentage of white votes.

The Democrats under Al Gore, by contrast, made every effort to cut into the Republicans’ white base. They did so with what was called the “class war” strategy, denouncing Big Business, promising free prescription drugs and health care for the elderly, and appealing to white union members. Washington Post political reporter Thomas Edsall noted this strategy during the campaign:

“Gore’s success in making inroads with working-class voters, especially white men, has been crucial to his improved standing in the battleground states of Michigan, Ohio and Missouri that hold the balance of power in the 2000 election. Among all voters in each of these states, Democrat Gore is either fully competitive with, or slightly ahead of Texas Gov. Bush, the Republican nominee.” Although Mr. Gore lost in two of these states, the strength of his challenge forced Mr. Bush to divert resources and attention he might have deployed elsewhere.

Coupled with his success in winning non-white voting blocs through appeals to fear and racial animosity, Mr. Gore won the popular vote for president and lost the electoral vote only after a series of agonizing recounts and court battles. Moreover, had Ralph Nader not been in the election, the vast majority of his votes would surely have gone to Mr. Gore, giving him the presidency without any post-election recounts.

The conclusion is inescapable: George W. Bush won the election not because his “compassionate conservatism,” “Big Tent,” or “Rainbow Republicanism” mobilized a majority of voters or attracted non-whites but because the political left was split between the Democrats and the Naderites. The Democrats won the popular vote and, despite the Naderite rebellion, nearly won the election because they explicitly appealed to and made use of the racial solidarity and racial consciousness that drives the majority of non-white voters, while at the same time using white working class economic anxieties to attract white voters and cut into the Republicans’ neglected political-demographic base.

For all the rhetoric among “new Republicans” about winning non-whites, the lesson of the 2000 election for the GOP ought to be clear: Trying to win non-whites, especially by abandoning issues important to white voters, is the road to political suicide; the natural and logical strategy of the Republican Party in the future is to maximize its white vote.

The party* could accomplish this by supporting a long-term moratorium on legal immigration, terminating welfare and other public benefits for immigrants, seeking the abolition of affirmative action, and working for the repeal of “hate crime” laws and the end of multiculturalism. The Republicans could become and remain a majority party by seeking to raise white racial consciousness; they do not need to appeal to irrational racial fears and animosities, but they can and legitimately should encourage white voters to (1) perceive that they as a group are under threat from racial and demographic trends and (2) believe that the Republican Party will support them against this threat.

Advocates of Rainbow Republicanism will argue that this is not possible or desirable, that it will only promote racial divisions, and that attracting more white voters than the Republicans now are able to win is not practical. This line of argument is wrong. Racial animosity is already being inflamed — by the Democrats’ willingness to exploit anti-white sentiments and by racial demagogues like Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, the NAACP, and analogous Hispanic activists. The only force that can quell or check this kind of anti-white racism is the solidarity of whites against it and those who try to use it for political gain.

As for winning more white votes, it is entirely feasible — as the 67 percent and 64 percent white majorities won by Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan in 1972 and 1984 show. It is quite true that neither Nixon nor Reagan ever did much to address white concerns once they won their votes, but a political leader who actually did seek to address their concerns could surely win that level of white support again.

Peter Brimelow has noted that, for all the Republican foreboding about the growing Hispanic and non-white presence in the electorates of California and other states, Southern whites now and historically have had to confront even larger racial disparities in the electorates of their own states. Blacks in the South constitute about 35 percent to 40 percent of the electorate and, there as elsewhere, vote as a bloc. Nevertheless, the largely white Republican Party in the South routinely manages to win majorities in these states for both presidential and many congressional and gubernatorial candidates. It is able to do so because white Southerners — far more than whites elsewhere — vote as a bloc. In the 2000 election, exit polls showed that whites in the South voted for Bush by 66 percent; in the three other regions (East, West, and Midwest), white voters supported Bush by an average of only 49 percent. Obviously, white racial consciousness remains highest in the South, though the election of 2000 shows that there is, among a small majority of whites and especially white men, at least a kind of racial subconscious in much of the rest of the country as well. Only if whites of both sexes and in all parts of the nation bring that subconscious to the surface and make it a real force in national politics can they expect to resist the racial politics that threatens them and their future.

*These comments should not be taken as an endorsement of or a commitment to the Republican Party or its leadership and platform. The strategy outlined here would be effective for the Republicans or for any other viable political party. There is no reason why it should be restricted to the Republicans, and there are in fact compelling reasons to doubt that the Republicans will use it.