White Man Visits the Black Republic

F. Roger Devlin, American Renaissance, May 31, 2013

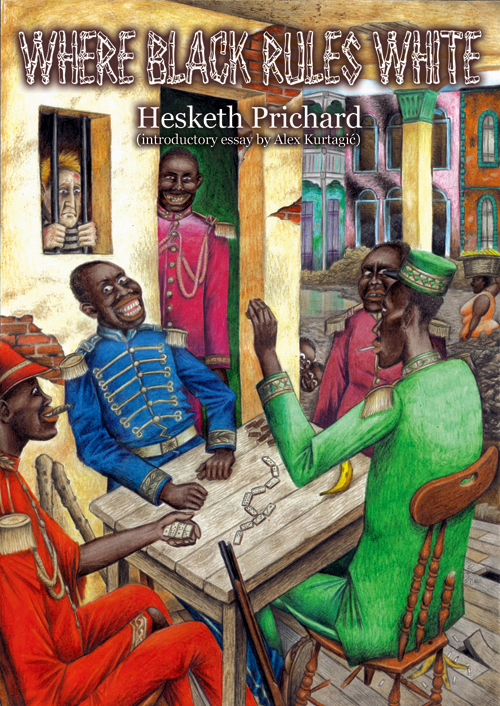

H. Hesketh-Prichard, Where Black Rules White: A Journey Through and About Hayti, Wermod and Wermod Publishing Group, 2013, 223+lxviii pages, $34.95 (hardcover), with a new introduction and annotations by Alex Kurtagic

Victorian adventurer Hesketh Vernon Hesketh-Prichard’s account of his 1899 visit to Haiti was reviewed here a year ago by Thomas Jackson, but we wish to call attention to this new deluxe reprint, which includes a 60-page introduction and 78 explanatory footnotes by AR contributor and 2012 conference speaker Alex Kurtagic.

Haiti began as the French colony of Saint-Domingue, “the Jewel of the Antilles,” exporting coffee, sugar, tobacco and indigo. By the 1780s, writes Mr. Kurtagic, 40 percent of all sugar and 60 percent of all coffee consumed in Europe came from Saint-Domingue, more than from all the British West Indian colonies combined. One small alluvial plain north of Port-au-Prince, 27 miles by 24 miles, was said to have the most fertile soil in the world, producing 20,000,000 francs in revenue (equal to about 90,000 ounces of gold) every year.

Yet the colony had one ominous weakness: an overwhelming dependence on African slave labor. During the later part of the 18th century, annual slave importation rose from 10 or 15 thousand to 40 thousand, with a total of some 1,000,000 brought in over the colony’s history. Mortality must have been high, however, for on the eve of the French Revolution, blacks numbered only about half a million. The remainder of the population consisted of some 25,000 free “coloreds” (mixed race) and between 28,000 and 39,000 whites. This meant life in the colony revolved around fear: the slaves’ fear of their masters and the masters’ fear of their slaves.

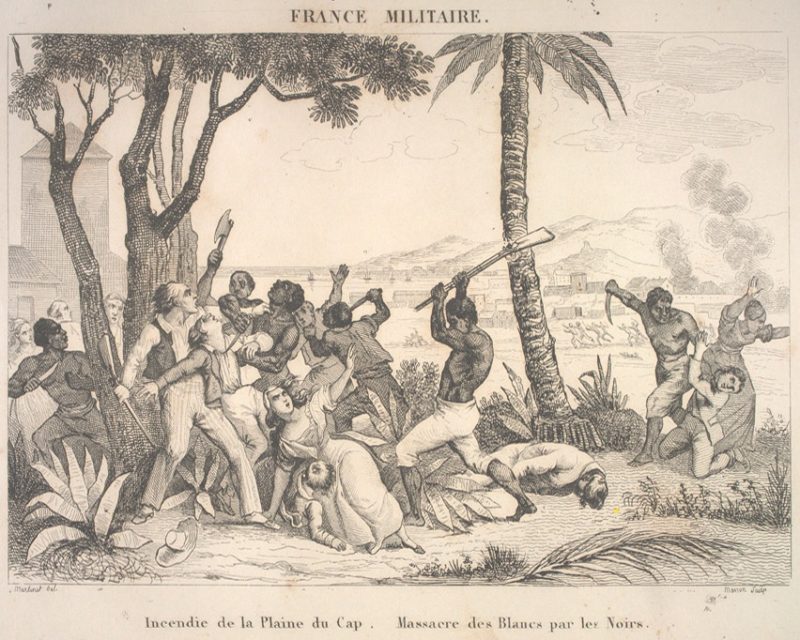

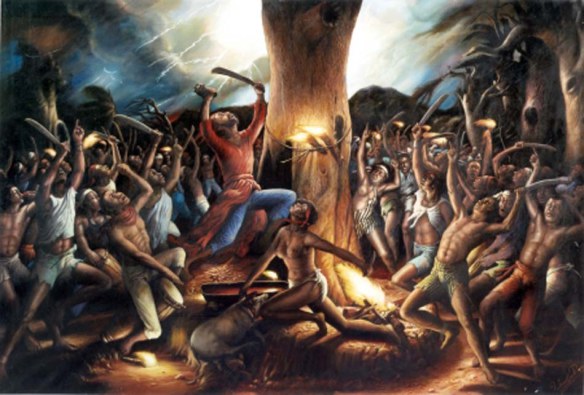

When the revolution broke out in 1789, the slogan of liberty, equality and fraternity insinuated itself into the African mind. Mr. Kurtagic notes that this led to “uprisings, riots, slaughter and destruction. Blacks and Mulattoes targeted the Whites, committing acts of unspeakable cruelty not unlike what we have seen in Black-ruled Zimbabwe and South Africa.” The whole ghastly story, complete with the various forms of torture employed upon the helpless whites, is recounted by Lothrop Stoddard in The French Revolution in San Domingo.

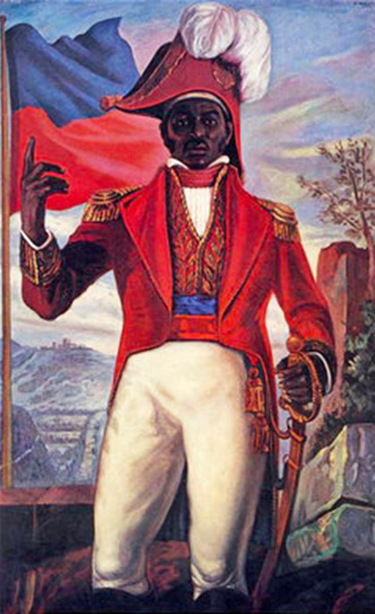

Napoleon briefly regained control, but his announcement of the reintroduction of slavery provoked another revolt. The black leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines declared Haiti an independent republic in 1804, and between January and March of 1805 his government systematically exterminated all surviving whites.

Since that time, Haiti has been governed much like the modern West African nations from which its population was taken: repeated coups and attempted coups, with each succeeding government resembling the last in venality and indifference to the public good.

When Hesketh-Prichard visited in 1899, the ruins of French plantations were still visible, though they were rapidly being reclaimed by the jungle. Cap-Haitien, the onetime “little Paris . . . the center of luxury and fashion,” lay in ruins. A small black-man’s city of ramshackle wooden huts lay amid the sprawling stone ruins like “a sparrow’s egg in an abandoned eagle’s nest.” The plain which had been so prodigiously fertile in the days of French rule now produced “not a red cent;” cultivation had been abandoned, and its black inhabitants were content to enjoy the mangoes that still grew from the now-wild vegetation.

The best Haitians were of the poorer classes, especially those in the rural districts. Hesketh-Prichard found them impeccably polite and generous with the pitifully little they had. But these simple, good-natured people bore the twin weight of degrading superstition and a parasitical official class.

Voodoo, the real religion of Haiti, was a combination of ecstatic dancing, animal- and occasional child-sacrifice, and the multifarious poisoning techniques of a class of voodoo priests known as “papalois.” Hesketh-Prichard’s one proposal for social reform was the physical elimination of this class.

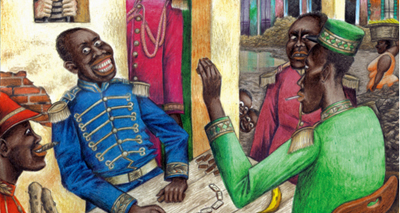

The Haitian army had more officers than enlisted men. Hesketh-Prichard claimed with only slight exaggeration that every third person he met in the country was a general. In rural districts local authority was exercised by such generals. They were often unpaid by the government and had to get their living by preying upon the people under their authority. The highest ambition of the common man was to be appointed general — which rarely required having to rise through lower ranks.

Urban areas enjoyed the protection of a police force armed with iron-tipped clubs called “coco macaques.” These men received no salary, but got a small sum for each person they arrested. When hungry, they could be observed arresting passers-by to collect enough for a meal. Conditions in the prisons were horrifying, and the prisoners were not fed. Escape “seemed to be childishly easy,” but the men did not have the enterprise to attempt it.

Readers may consult Thomas Jackson’s review for a more detailed account of Hesketh-Prichard’s observations.

As Mr. Kurtagic writes in his introduction, Haiti has deteriorated since Hesketh-Prichard’s visit. The jungle has been nearly all cut down, causing the erosion of most of Haiti’s fertile soil. A large percentage of public services are provided only by international aid agencies. More than two-thirds of the labor force have no formal employment. At present, 9,000 UN troops are struggling for control against a variety of criminal gangs.

For me, the highlight of this new edition is the last section of the introduction, in which Mr. Kurtagic skewers the notion of “development.” As he observes, this idea derives from a specifically modern, Western ideology of progress, whose origins can be found in European thinkers such as Locke, Kant and Adam Ferguson. Development theorists believe that all countries are destined to become modern, secular, industrial, and democratic. Yet such an ideal presupposes a population that is, if not European, at least shares certain important traits with Europeans, such as intelligence, industriousness, conscientiousness, and impulse control.

West Africans, whether in West Africa or Haiti, want the comforts and conveniences of the Western economic model, but are not committed to the attitudes and behavior necessary to sustain that model. Attempts by the white man to impose “development” on such people are doomed, because they do not take into account the character of the local population.

Hesketh-Prichard is one of a long train of observers who have described West Africans as gregarious, boastful, lazy, excitable, aggressive, spontaneous, warm and relaxed. These qualities can be explained with reference to three largely heritable, essentially racial, traits: low intelligence, low conscientiousness, and high testosterone levels. Africans in their turn view whites as uptight (a term that originated among American blacks), shy, weak, cold, boring, narcissistically self-analytical, and obsessed with counting — also racial traits.

Therefore, it is normal for West Africans and Europeans to build very different kinds of societies. As for “aid” to countries like Haiti, as Mr. Kurtagic notes, “rather than persist in throwing ever more resources into a counter-productive effort to impose Westernization on non-Western peoples, Western intellectuals and politicians need to be thinking in terms of the de-Westernization of Europe’s former colonies; they need to accept that ‘development’ is not the solution, but the problem.”

Foreign aid creates unhealthy dependency and encourages reckless procreation that requires ever-higher levels of aid. Haitians would be better served by a simple economy based on herding, subsistence farming, and traditional arts and crafts. This would keep the population within sustainable bounds and, if Hesketh-Prichard’s observations of the rural poor are to be trusted, might even bring out the best in their African nature.