April 1994

| American Renaissance magazine | |

|---|---|

| Vol 5, No. 4 | April 1994 |

| CONTENTS |

|---|

How Legends are Created

The Doctor in Spite of Himself

O Tempora, O Mores!

Letters from Readers

| COVER STORY |

|---|

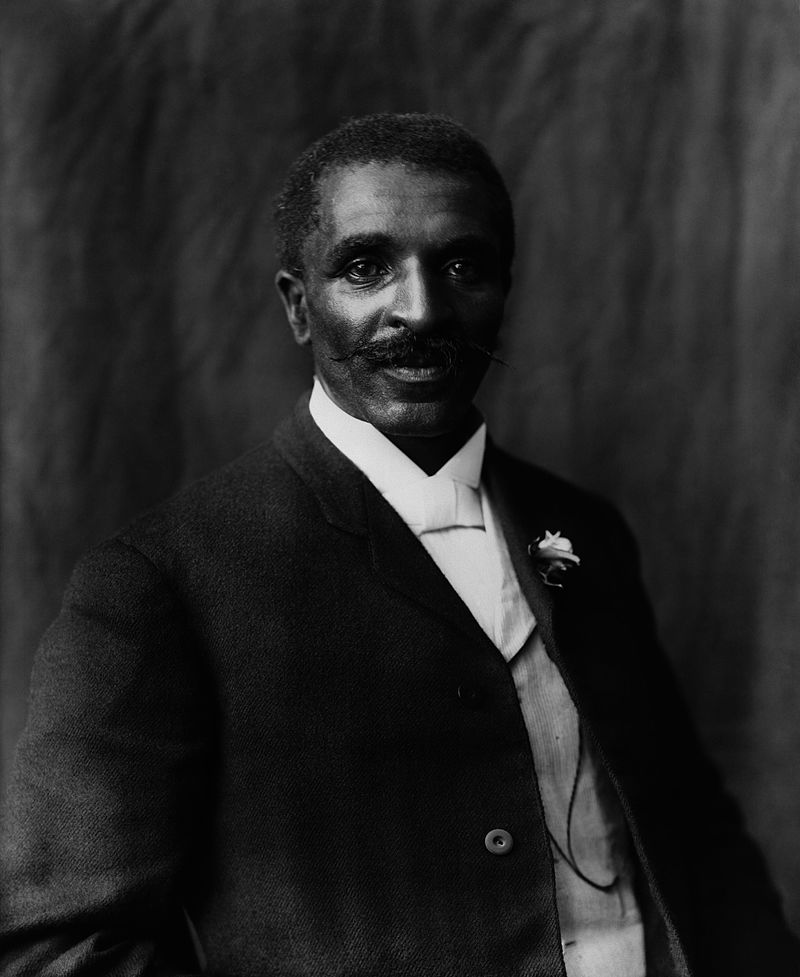

How Legends are Created: The Counterfeit Glory of George Washington Carver

There was affirmative action long before it had a name.

by Marian Evans

George Washington Carver

The discovery and promotion of black “role models” is now an important industry. It lifts long-dead cowboys, inventors, and ship captains from obscurity and presents them as significant figures ignored by racist white society. It accounts for why so many unknown blacks suddenly appear on postage stamps or in black-history-month displays.

George Washington Carver is very much the reverse. He was a legend in his own time, as the man who brought modern agriculture to the South and who discovered hundreds of ingenious new uses for the peanut. Along with people like Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. DuBois, he is a central figure in the history of black achievement, but his fame is absurdly out of proportion to his meager accomplishments. How did a good and engaging but unremarkable man win a reputation as a brilliant scientist long before affirmative action? His story, like that of Martin Luther King’s plagiarism, says more about white people than about the man himself.

Traded For a Horse

Carver was born in Missouri during the last years of slavery, probably in 1864. An important part of the Carver myth is the dramatic story of his abduction when he was no more than six months old. “Night riders” made off with him and his mother with the intention of selling them in the deep South. Their owner, Moses Carver, did everything within his power to get the mother and child back, but managed to have only the child returned — in exchange for a horse. Biographers would later call it “the most valuable horse in American history.”

After emancipation, his owners kept him as a foster child and did their best to educate him. Through persistence and despite hardships, Carver earned bachelors and masters degrees in agriculture, and in 1896 was hired by Booker T. Washington at the Tuskegee Institute. He spent his entire career at Tuskegee and it was there that he built his reputation as the great peanut genius.

According to the official story, Carver quickly turned the loss-making farm at the Tuskegee Experiment Station into a money-maker and set about instructing Southerners in modern agricultural methods that transformed the region. His first known involvement with peanuts was in 1903, and his first serious effort to promote their cultivation was a 1916 bulletin called How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing It for Human Consumption.

According to the myth, it was Carver who, almost single-handedly, introduced crop rotation to the monoculture South and it was his substitution of peanuts for cotton that saved the region from the boll weevil. Then, appalled that he had promoted peanuts to the point of overproduction and falling prices, he rushed into the laboratory and invented hundreds of profitable new ways to use the crop. As we shall see, the truth is quite different.

Carver was, nevertheless, an enthusiastic spokesman for the peanut, and in 1920, the United Peanut Association of America invited him to address its convention. This was a calculated public relations measure by the newly-formed association. There was news value in having a black man address its convention and in Carver’s entertaining claims for 145 different, practical uses for the peanut.

The association, which was lobbying Congress for a protective tariff, then sent Carver to Washington to present the peanut to the House Ways and Means Committee. Some of the legislators treated him with amused condescension, but by showing them samples of peanut soap, peanut face cream, peanut paint and a host of other improbable products, he held their attention for nearly two hours — far longer than the 10 minutes originally allotted him. This appearance was widely reported and was an important step towards fame.

Carver became a favorite on the exhibit and lecture circuit, and his laboratory was opened to admiring visitors from all around the world. The number of peanut products continued to grow, with a final tally of something around three hundred. The wizard turned his attention to other lowly plants and reported over 150 uses for the sweet potato. He reportedly made synthetic marble from wood shavings and paint from cow dung. By the 1930s, he was the legendary “Mr. Peanut,” and admiring articles appeared about him everywhere. An early issue of Life magazine published photographs of the great man.

Carver’s death in 1943 prompted countless newspaper eulogies. President Franklin Roosevelt’s statement on the occasion — “The world of science has lost one of its most eminent figures . . .” — was typical of public pronouncements across the nation. Senator Harry Truman introduced a bill to make Carver’s birthplace a national monument. It passed without a single dissenting vote, making Carver only the third American to be so honored, along with George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. A new star had joined the American firmament.

The Real Record

What were Carver’s real achievements? The mainstays of his fame are easily unstrung. First of all, he was unable to make the Experiment Station farm profitable. He was interested in laboratory work, not administration, and had no talent for scheduling and overseeing the black students who worked the farm. His boss, Booker T. Washington, upbraided him for his failure to make the farm pay and pointed out that Carver did not even practice the sensible agricultural methods he preached to others.

Far more important is the question of his influence on peanut production. National production records show that the crop doubled from 19.5 million bushels to over 40 million bushels from 1909 to 1916, a rise that the Department of Agriculture called “one of the striking developments that have taken place in the agriculture of the South.” However, the increase took place before the publication of Carver’s first peanut tract, How to Grow . . . arid 105 Ways . . . and before he seriously promoted the crop.

During the 1920s, when Carver was enthusiastically boosting the peanut, national production actually fell. In Alabama, the state in which Carver worked, the 1917 peak was not reached again until the mid-1930s — and with little help from Macon County where Tuskegee is located. Carver himself noted sadly in 1933, that few peanuts were grown on the farms nearest to and most easily influenced by the institute. It is undoubtedly true that his peanut evangelism persuaded some to grow the crop, but his influence was by no means decisive.

What of the miraculous products Carver derived from the peanut? In 1974, the posthumously established Carver Museum at the Tuskegee Institute listed 287 peanut products, but much duplication inflates the figure. Bar candy, chocolate-coated peanuts, and peanut-chocolate fudge are listed as separate items, as are face cream, face lotion, and all-purpose cream. No fewer than 66 of the 287 products are dyes — 30 for cloth, 19 for leather and 17 for wood.

Many of the products were obviously not invented or discovered by Carver — “salted peanuts” are on the list — and the efficacy of many, including a “face bleach and tan remover” cannot be guaranteed or even tested. Astonishingly enough, Carver did not record the formulas for his products, so it is impossible to reproduce or evaluate them.

Although the popular understanding about Carver is that he launched whole industries that ran on peanuts, scarcely any of his products were ever marketed, and his commercial and scientific legacy amounts to practically nothing. He was granted only one peanut patent — for a cosmetic containing peanut oil — but this slim achievement was interpreted as pure generosity. “As each by-product was perfected,” wrote one admirer in 1932, “he gave it freely to the world, asking only that it be used for the benefit of mankind.”

Little benefit ensued because he never explained how to make the things he claimed to have discovered. In 1923, for example, Carver announced “peanut nitroglycerin” in a article called “What is a Peanut?”, published in Peanut Journal. He cheerfully reported that “This industry is practically new but shows great promise of expansion;” in fact, there was no peanut nitroglycerin industry and never would be. It is impossible to confirm if there was ever even any peanut nitroglycerin.

Other promising products were announced in articles with titles like “The Peanut’s Place in Everyday Life,” “Dawning of a New Day for the Peanut,” and “The Peanut Possesses Unbelievable Possibilities in Sickness and Health.” These possibilities remained largely as he characterized them: unbelievable.

Carver’s methods can be attributed, in part, to his gifted laboratory assistant. He recounted to many audiences how he turned to God in the despair of learning that farmers, following his advice, had produced a peanut glut:

‘Oh, Mr. Creator,’ I asked, ‘why did you make this universe?’ And the Creator answered me, ‘You want to know too much for that little mind of yours,’ He said.

So I said, ‘Dear Mr. Creator, tell me what man was made for.’

Again He spoke to me: ‘Little man, you are still asking for more than you can handle. Cut down the extent of your request and improve the intent.’

And then I asked my last question. ‘Mr. Creator, why did You make the peanut?’

‘That’s better!’ the Lord said, and He gave me a handful of peanuts and went with me back to the laboratory and, together, we got down to work.

On at least one occasion, Carver told a church audience that he never needed to consult books when he did his scientific work; he relied exclusively on divine revelation.

An Appealing Old Wizard

Upon close examination, therefore, “the Wizard of Tuskegee” resembles a different wizard of stage and movie fame. How did he become, as Reader’s Digest put it in 1965, “a scientist of undisputed genius”?

His appealing personal qualities certainly helped. He was genuinely uninterested in money, and refused to accept a pay raise during his entire 46 years at Tuskegee. When a group of Florida peanut growers sent him a check for diagnosing a peanut disease, he returned it, saying, “As the good Lord charged nothing to grow your peanuts I do not think it fitting of me to charge anything for curing them.”

He was also a black man segregationists could love. He was unmarried and celibate, apolitical, and always deferential. He really did “shuffle” and “shamble” wherever he went, and journalists enjoyed saying so.

A 1937 Reader’s Digest article written at the height of his fame begins with these words:

A stooped old Negro, carrying an armful of wild flowers, shuffled along through the dust of an Alabama road . . . I had seen hundreds like him. Totally ignorant, unable to read and write, they shamble along Southern roads in search of odd jobs. Fantastic as it seemed, this shabbily clad old man was none other than the distinguished Negro scientist of the Tuskegee Institute . . .

In 1923, the Atlanta Journal wrote happily of Carver that “He combines all the picturesque quaintness of the ante-bellum type of darkey [with] . . . the mind of an amazing scientific genius . . .”

Even after he became famous, Carver never attempted to cross the color bar, even declining invitations to eat with whites. After the death of the equally accommodating Booker T. Washington in 1915, Carver took his place as the nation’s foremost docile but achieving Negro.

There is also no doubt that Carver himself helped inflate his reputation. He did not explicitly claim to have invented all the products he spoke of, but he glossed over the difference between invention and list-making in a way that can only have been deliberate. When given an opportunity to correct exaggerated claims on his behalf, he did so in humorously humble ways that no one took seriously. On taking the podium, he might say, “I always look forward to introductions about me as good opportunities to learn a lot about myself that I never knew before.” To an author who had written of him favorably, he wrote, “How I wish I could measure up to half of the fine things this article would have me be.”

When asked for details about his inventions, he might reply, “I do dislike to talk about what little I have been able, though Divine guidance, to accomplish.” George Imes, who served for many years on the Tuskegee faculty with Carver, later wrote of his “enigmatic replies” to queries from scientists. To a writer who asked in 1936 for material on the practical applications of his discoveries, Carver replied that he simply could not keep up with them.

Of course, there always were people who knew that the reputation was a soap bubble, but they kept quiet. In 1937, the Department of Agriculture replied thus to a request for confirmation of Carver’s achievements:

Dr. Carver has without doubt done some very interesting things — things that were new to some of the people with whom he was associated, but a great many of them, if I am correctly informed, were not new to other people . . . I am unable to determine just what profitable application has been made of any of his so-called discoveries. I am writing this to you confidentially. . . and would not wish to be quoted on the subject.

In 1962, the National Park Service commissioned a study of Carver’s scientific achievements in order to best represent them at the George Washington Carver National Monument. Two professors at the University of Missouri turned in such an unflattering report that the Park Service’s letter of transmittal recommended that it not be circulated:

While Professors Carroll and Muhrer are very careful to emphasize Carver’s excellent qualities, their realistic appraisal of his ‘scientific contributions,’ which loom so large in the Carver legend, is information which must be handled very carefully . . . Our present thinking is that the report should not be published, at least in its present form, simply to avoid any possible misunderstanding.

By the 1950s, a few realistic appraisals of Carver’s career had appeared in print, and the 1953 edition of the 1700-page Webster’s Biographical Dictionary has no entry for him at all. Naturally, he has been rehabilitated in subsequent editions, and at a time when virtually any black of modest attainments is fair game as a “role model,” Carver’s chances of resting in peaceful obscurity are slim to none.

From today’s perspective, one of the most significant aspects of the Carver legend is that it grew to giant proportions in a segregated America that had never dreamed of quotas or busing and in which virtually no one believed blacks to be the intellectual equals of whites. It is instructive — and sobering — to realize that even then the affirmative action impulse was at work in the minds of whites.

The single best source for material on the Carver legend is “George Washington Carver. The Making of a Myth,” which appeared in The Journal of Southern History, November 1976 It contains excellent bibliographic material and was an important source for this article.

| BOOK REVIEW |

|---|

The Doctor in Spite of Himself

An astonishing tale of misbehavior and the cover-up that followed.

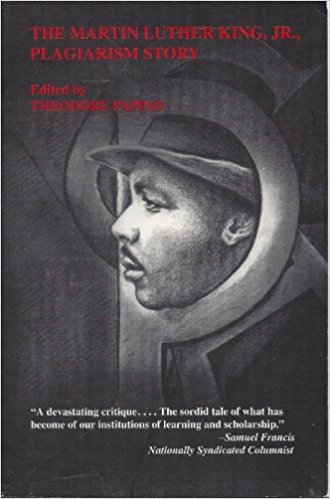

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Plagiarism Story, Theodore Pappas (Ed.), The Rockford Institute, 1994, 107 pp.

Reviewed by Thomas Jackson

Late in 1987, a graduate student working on the project to publish the collected papers of Martin Luther King discovered that King had plagiarized huge parts of his doctoral dissertation. Clayborne Carson, the director of the project, decided to suppress this fact, thus setting in motion one of the most sordid tales of academic dishonesty and race-based special pleading in recent memory.

This book is an invaluable collection of several accounts of what King did and of the contemptible coverups and justifications that followed. Not surprisingly, its editor, Theodore Pappas, could not find a commercial publisher, so the book is unlikely to be in book stores or even in libraries. Only if enough people buy and read it will its story survive the whitewash.

Starting Early

It is now clear that King began plagiarizing as a young man and continued to do so throughout his career. At Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, where he received a bachelor’s degree in 1951, his papers were stuffed with unacknowledged material lifted verbatim from published sources. The King papers project has dutifully collected this juvenilia, and Mr. Pappas explains how it strikes the reader today:

King’s plagiarisms are easy to detect because their style rises above the level of his pedestrian student prose. In general, if the sentences are eloquent, witty, insightful, or pithy, or contain allusions, analogies, metaphors, or similes, it is safe to assume that the section has been purloined.

Mr. Pappas notes that in one paper King wrote at Crozer, 20 out of a total of 24 paragraphs show “verbatim theft.” King also plagiarized himself, recycling old term papers as new ones. In their written comments on his papers, some of King’s professors chided him for sloppy references, but they seem to have had no idea how extensively he was stealing material. By the time he was accepted into the PhD program at Boston University, King was a veteran and habitual plagiarist.

Some of the most devastating parts of Mr. Pappas’ book are nothing more than side-by-side comparisons of material from King’s PhD thesis and from the sources he copied without attribution. King was overwhelmingly dependent on just one source, a dissertation written on the same subject as his own — the German-born theologian, Paul Tillich — by another Boston University student named Jack Boozer.

Here is a typical passage from King’s thesis that is lifted, word for word, from Boozer’s:

Correlation means correspondence of data in the sense of a correspondence between religious symbols and that which is symbolized by them. It is upon the assumption of this correspondence that all utterances about God’s nature are made. This correspondence is actual in the logos nature of God and logos nature of man.

There is word-for-word copying throughout the thesis. Mr. Pappas notes that the entire 23rd page is lifted straight out of Boozer, and that even when King was not stealing Boozer’s words without attribution, he was stealing his ideas: “There is virtually no section of King’s discussion of Tillich that cannot be found in Boozer’s text.”

Even when King is “quoting” Tillich, complete with footnotes, he may actually be quoting Boozer. Boozer occasionally typed the wrong page number in a Tillich footnote, or made an error transcribing Tillich’s words. King copied the errors along with everything else.

King’s plagiarism is even more breath-taking than it seems. Boozer was not just any B.U. graduate student. He had written his thesis in 1952, only three years before King wrote his, and had submitted it to the same advisor. Since the advisor is now dead, we will never know whether he failed even to notice the copying or was simply practicing early affirmative action. The second faculty reader of King’s thesis now excuses himself by saying he read it early in his career, at a time when he was naive about plagiarism.

Even after he became famous, King continued to plagiarize. His “Letter From Birmingham City Jail,” is now known to contain passages he had cribbed so often that he knew them by heart. Some of the best-known passages from his “I Have a Dream” speech are taken from a 1952 address by a black preacher named Archibald Carey. His Nobel Prize Lecture and his books, Strength to Love and Stride Toward Freedom, are also extensively plagiarized.

Moreover, it is clear that King did not take from others because he thought ideas and words were common property. He copyrighted the “I Have a Dream” speech, pilferings and all, and vigorously defended it against unauthorized use. King’s estate continues to enforce the copyright. Only last year, in a paroxysm of adulation, USA Today printed the full text of the speech, beginning on the front page. The estate sued.

Shielding the Saint

Like his penchant for adultery, King’s intellectual dishonesty does not sit well with his reputation as Saint and Great Man. Perhaps it is because they reveal other failings that his FBI files are still sealed. King, alone of all Americans, is honored with a national holiday, and it is awkward for a saint to be caught stealing. The line of defense has been predictable: He didn’t do it, and if he did, it doesn’t matter.

A three-year cover-up began with Mr. Carson and his staff at the King papers project. He forbade anyone to use the word “plagiarism,” and has since written of the “similarities” and “textual appropriations” that were part of King’s “successful composition method.” Mrs. Coretta Scott King also appears to have played a role in the cover-up by refusing to release King’s handwritten dissertation notes. Mr. Carson deliberately misled reporters who had heard rumors of plagiarism, and came clean with the facts only when it became clear that the story would break anyway.

The project leader’s disingenuousness has not affected funding for the King papers. They have probably swallowed up nearly a million dollars in tax money as well as support from the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations, IBM, Intel and many other donors. In eight years, the project has published only one volume of a projected fourteen.

To the profound discredit of the American press, it was a British paper, the Sunday Telegraph, that first published a story, in December, 1989, about allegations of plagiarism. It was not until nearly a year later, in November, 1990, that the Wall Street Journal reported the story to a large American audience. Chronicles had briefly mentioned the rumors a little earlier, and Mr. Pappas had prepared a thorough exposé but was beaten into print by the nimbler Journal. It is now established that the New York Times, Washington Post, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and New Republic all had heard about the plagiarism but had decided not to investigate it.

Once the truth was out, official reactions were just as craven. The Wall Street Journal wrote a typically lickspittle editorial, arguing that King’s plagiarisms do not reflect on his character but “tell something about the rest of us. [!?]”

Boston University formed a committee to look into the matter and concluded that since King had stolen only 45 percent of the first part and 21 percent of the second part of his dissertation, it was an “intelligent contribution to scholarship” and that “no thought should be given to revocation of Dr. King’s doctoral degree.” The second reader of the thesis actually defended the plagiarism by saying that King had accurately conveyed Boozer’s thinking — something not hard to do, since King copied him verbatim.

Boozer, who lived just long enough to learn of the plagiarism, was perhaps the greatest groveler of all. As his wife later explained, “He told me he’d be so honored and so glad if there were anything that Martin Luther King could have used from his work.”

Keith Miller of Arizona State University has already written a full-length exculpation of King called Voice of Deliverance: The Language of Martin Luther King, Jr. Mr. Pappas notes that Prof. Miller has come up with an astonishing variety of ways to say “plagiarism” without using the word: voice merging, intertextualization, incorporation, borrowing, consulting, absorbing, alchemizing, overlapping, quarrying, yoking, adopting, synthesizing, replaying, echoing, resonance, and reverberation.

Prof. Miller says that non-whites, who have strong oral traditions, should not be held to stuffy, Western standards of bibliography and that King could not be expected to understand the demands of an alien white culture. “How could such a compelling leader commit what most people define as a writer’s worst sin?” he asks; “The contradiction should prompt us to rethink our definition of plagiarism.” Since Martin Luther King did it, it must be all right.

Even those who condemn plagiarism claim to have no idea why King should have done it. Mr. Pappas drops us a hint when he writes, “[W]e know from his scores on the Graduate Record Exam that King scored in the second lowest quartile in English and vocabulary, in the lowest ten percent in quantitative analysis, and in the lowest third on his advanced test in philosophy — the very subject he would concentrate in at B.U.” People steal ideas when they are too lazy or unoriginal to come up with their own.

Blacks and Whites

Of course, the story that Mr. Pappas tells says far, far more about white America than about Martin Luther King. King was a dishonest scholar and got away with it — a small-time con-man whose degree would be revoked if Boston University had any integrity.

There is no doubt about what would have happened had King been white. Mr. Pappas reminds us that Joseph Biden’s bid for the presidency ended when he was shown to have copied from a speech by Neil Kinnock, the British Labor Party leader. Boston University itself recently stripped a dean of his position when it was learned he had cribbed from a Wall Street Journal article for a commencement address.

There is not a single white person, dead or alive, whose reputation academics and journalists would go to degrading lengths to preserve, but blacks are different. It is now well established that Alex Haley, the author of Roots, did not merely fake his African family tree but stole parts of it from a novel by a white man. His reputation remains unsullied, his Pulitzer Prize unrevoked. The black poet Maya Angelou’s “Inauguration Poem” likewise appears to have been an unattributed adaptation, but her reputation and academic sinecure are unshaken.

To criticize Maya Angelou or Arthur Haley is merely in bad taste but to question the sanctity of Martin Luther King is lèse majesté. Why?

In his forward to this book, Jacob Neusner writes that the impulse to defend a shameless plagiarist “stems from insufficient faith in the authentic achievements of Martin Luther King . . .” In other words, anyone who does not find room in King’s spacious personality for a few personal failings does not grasp the man’s true greatness. Nonsense.

People toady to King’s memory because he is a symbol of white racial atonement. To evoke his name is to confess white sinfulness and to ask forgiveness. Any attitude towards him other than worshipfulness suggests insufficient yearning for atonement or, to call it by its every-day name, racism.

To go further and actually criticize King is to risk more than the taint of bigotry; it is to insult the contemporary idea of America itself. King’s birthday is a holiday because he symbolizes what is thought to be America’s finest triumph — the triumph over white wickedness. King stands for integration and racial egalitarianism, from which flow quotas, multiculturalism and non-white immigration. Policies that will weaken the country and dispossess the white majority must have nothing less than a saint as their symbol.

| IN THE NEWS |

|---|

O Tempora, O Mores!

Poverty Law Center is Rich and Devious

The Montgomery Advertiser has just published a sweeping, nine-part exposé of one of the country’s best known anti-racist organizations, the Southern Poverty Law Center in Alabama. The paper has concluded that the center, run by Morris Dees, has wildly exaggerated the threat of the Ku Klux Klan in order to get money out of liberal whites. It has been spectacularly successful. Since 1984, the center has brought in about $62 million in contributions. During this period, it had investment income of $22.1 million, which is more than it spent on programs.

One of the center’s favorite tactics is to bring civil suits against Klansmen and racialists in order to bankrupt them. In a series of fund-raising letters, it implied that it had squeezed $7 million dollars out of a Klan group for the benefit of the mother of a lynching victim. In fact, the mother got only $51,800 from the impoverished Klansman, while the center collected millions of dollars through the appeal.

The Montgomery Advertiser also notes that the center has had a very bad record with black employees. It has hired very few and many of these have left, complaining of everything from paternalism to racial slurs.

Yo, Man!

At one time, academics predicted that black dialect would disappear as blacks learned to speak standard English. The reverse is happening. Linguists report that underclass blacks are speaking a language that is steadily diverging from the mainstream. One reason is that many blacks refuse to speak “white” English and taunt other blacks who do. Some teachers in black schools have given up trying to correct their students’ grammar, while others teach English as a second language.

Even ghetto blacks understand standard English because they hear it on radio and television. However, as black vernacular devolves, it may soon become completely incomprehensible to whites.

Bad Rap

Every year, the NAACP gives Image Awards to blacks who are credits to their race. This year, it plans to give one to a “gangsta rap artist” named Tupac Shakur. Mr. Shakur is currently facing two separate criminal charges, one for rape and the other for wounding an off-duty policeman in a shootout. The National Political Congress of Black Women, which had denounced Mr. Shakur’s smutty recordings even before he got in trouble with the law, asked the NAACP not to give him an award. The NAACP executive board took a vote and decided to honor Mr. Shakur as planned. “This is an issue concerning the cultural self-determination of the African-American community,” explained Executive Director Ben Chavis, presumably with a straight face.

Meanwhile, in Miami, Florida, a white county commissioner has proposed that another rapper, Luther Campbell of 2 Live Crew, be given a seat on the local cultural affairs council. The rest of the commission, including all its black members, rose up in alarm, cited Mr. Campbell’s degeneracy, and defeated the plan. Jesse Jackson then criticized the black commissioners for not promoting a fellow black. “They elect those black commissioners and then they sell us down the road,” he complained.

Into the Sunset

Making famous men out of unknown blacks can be risky — and expensive. The Postal Service decided to include black cowboy, Bill Pickett, in its “Legends of the West” postage stamp series, but he is so far from being a legend that no one knew what he looked like. Engravers mistakenly put a likeness of his brother Ben on a stamp and ran off 20 million sheets before anyone noticed. Truck loads of stamps have been recalled and destroyed. Taxpayers will be billed about $1.1 million for the mistake.

Progress on Anti-White Bias Cases

The federal appeals court has ruled that a white employee of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, DC can sue for racial discrimination. A lower court had actually ruled that because he was not a member of a protected group he had to prove systematic discrimination against all whites rather than simple racial discrimination against himself.

A white doctor has won $480,000 in damages in a discrimination suit against the Chicago Transit Authority. William McNabola, who specialized in workers’ compensation claims, was fired from the transit authority in 1986. The Seventh Circuit Court noted in its ruling that the authority was guilty of many kinds of discrimination. At one point, more than 70 percent of the independent-contract lawyers used by the authority were black even though only three percent of Chicago’s lawyers are black.

In St. Louis, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has come to the defense of white police officers. The city adopted an affirmative action program in 1980 that required bypassing more eligible white men so as to hire women and non-whites. In one of its exceedingly rare actions on behalf of whites, the EEOC pronounced the system illegal.

High-Priced Immigrants

Donald Huddle, a Texas economist, has calculated that in 1992, immigrants — both legal and illegal — cost American tax payers $42.5 billion in direct costs alone. That figure reflects government spending of $62.7 billion (public schooling, Medicaid, welfare, food stamps, bilingual education, and the unemployment compensation paid to Americans pushed out of jobs) minus the $20.2 billion in taxes paid by immigrants. Of course, on top of this, immigrants got a free ride for all government services that are not considered handouts: police and fire protection, highway construction, libraries, parks, military security, etc. Also not included in Prof. Huddle’s reckoning are crowding, pollution, and environmental compliance costs for millions of newcomers, as well as the disproportionate crime rates of immigrants. The cost of cultural and racial displacement is beyond calculation.

Congress prefers to look the other way. In March, the House soundly defeated a bill that would merely have asked local school districts to keep count of how many illegal aliens they were educating. Opponents of the measure said that such a count would be reminiscent of Nazi Germany.

Non-Citizens Welcome

The California city of Milpitas has appointed a non-citizen, Mohan Trikha, to the city’s planning council. One council member, Barbara Lee, vigorously opposed the move, and the city considered drafting a regulation requiring all appointees to be citizens and registered voters. The city backed down when it realized that this would disqualify many non-whites. The city council is now all white and most members feel just awful about that. One councilor explained that he feared a citizenship requirement could be construed as an obstacle to involvement by non-whites in city government.

Back to Cuba

A black Alabama state representative, Alvin Holmes, is well known for his single-minded promotion of the interests of blacks. Earlier this year, when the state legislature was considering a bill that would make it easier for the state police to help deport foreign criminals, Rep. Holmes took particular aim at Cubans:

‘They all ought to be sent back to Cuba, including the ones that aren’t in jail . . . They don’t do nothing but hurt the blacks. They all ought to be sent back . . . I wish every one of their citizenships would be taken.’ Not to be thought prejudiced, Rep. Holmes went on to recommend that all people from Norway, Sweden, Ireland, France, Germany and El Salvador be repatriated too.

Besides his duties as a legislator, Rep. Holmes is a professor of history at Alabama State University.

Heart of Darkness

Southern Zaire has some of the richest copper and cobalt mines in the world At one time, mineral exports accounted for two thirds of the country’s foreign exchange. Now, the New York Times tells us, after the collapse of what passed for a government, and successive waves of ethnic warfare, the whites who ran the mines have gone back to Europe. What used to be an industry that employed thousands has collapsed into a tangled wasteland of rusting machinery. In most places, the only “mining” is done by ragamuffins who shovel through slag heaps looking for scraps of copper.

The same newspaper — and reporter — also wrote about the recent funeral for Felix Houphouet-Boigny, who ran the Ivory Coast in extravagant, self-aggrandizing fashion for 34 years. The story described the country as “rooted spiritually some where between the brutal competitiveness of Western commerce and the brilliantly complex and often mystical culture of ancient Africa.”

Truth in Surprising Places

U.S. Sen. Richard Shelby, a Democrat from Alabama, says he is against current immigration policies that will reduce whites to a minority. He called current policy a “horror story.” The usual people are calling him the usual names.

This Happy, Happy Land

In January, a lady sailor, who claimed not to know she was pregnant, gave birth to a baby boy on board the destroyer tender Yellowstone. It is thought to be the first time in U.S. naval history that a sailor has ever had a baby on board ship.

A black man who shot and wounded a white man in the hope of starting a race war got a 20-year prison sentence. Last March, Darryl Arnold bought a 9 mm pistol in a Los Angeles gun store, walked out, and shot the first white man he saw.

On Jan. 2, 1994, the Sacramento Bee published a guest editorial that contained this surprising line: “Stripped of its euphemistic clichés, multiculturalism’s fundamental characteristic is its hostility to the majority culture of white America.” The author, Lance Izumi, is a Japanese American.

For the first time in its 131-year history, the IRS will publish tax forms in a language other than English. 1040A short forms in Spanish will be distributed in California and South Florida.

During earthquake relief in Los Angeles, the Federal Emergency Management Agency posted signs all over town, in Spanish and English, telling people that aid was available to everyone, including illegal immigrants.

Catalina Vasquez Villapando, the first-ever lady Hispanic treasurer of the United States, has been charged with tax evasion, obstruction of justice, and conspiracy to falsify documents. She could get 15 years in prison and $750,000 fine. Her signature still appears on currency being printed today.

A veteran teacher in the Montgomery County, Virginia schools has been put on leave and could be fired for telling a class that when blacks move into neighborhoods, the crime rate goes up and whites decamp. “I guess we’ll have to move to Norway,” were some of Albin Wozniak’s impermissible words.

On the Bandwagon

It was only a matter of time. American Arabs have noticed that there are real advantages to being an official, protected minority. There are 870,000 Arabs in the United States, and many are determined to persuade Congress to grant them victim status just like blacks, Hispanics, and everyone else. Being a victim in America cannot be all bad; in 1992, 27,000 more Arabs took the risk and immigrated.

One of the largest concentrations of Arabs is in Detroit, and they have already gotten the Michigan departments of Mental Health and Public Health to give them money for multicultural and minority programs. Some colleges also include Arabs in affirmative action programs. If Congress blesses their efforts, Arabs will be able to claim preferences across the board.

Black Flight

The Los Angeles Sentinel is one of the oldest and largest black newspapers in the country. Founded in 1933, it has long had its offices on Central Avenue in South-Central Los Angeles. This used to be the black part of town, but is now dominated by Hispanics. This year, the paper upped stakes and moved to the Crenshaw district, to which most blacks have moved. Blacks, just like whites, flee the encroachment of people unlike themselves.

Shop ’Til You Drop

Walter Wilbon is a Chicago black man who openly admits that he conned the Social Security system into paying him $465 a month in disability benefits. However, it is in his off-the-books job — milking Medicaid — that he shows real resourcefulness.

Mr. Wilbon’s routine is not hugely lucrative for him — he makes about $100 on a good day — but in 1991 it cost taxpayers exactly $101,422.62 in Medicaid charges. His hustle is simple: Get free prescriptions for diseases he does not have and sell the medicine on the black market. Many Medicaid recipients do this, but Mr. Wilbon is remarkable for his persistence. City records show that in 1991, he made 426 doctor’s visits (to 111 different doctors) and got more than $87,000 worth of free prescriptions. He has studied enough to know just what symptoms to claim, and when that doesn’t work he browbeats doctors into writing prescriptions.

On his most successful day, March 14th, he walked home with $1,136.04 worth of medicine and medical equipment. He also steals anything he finds in doctors’ offices. The difference in his year’s prescription costs — $87,000 — and his total Medicaid bill — $101,422 — is accounted for by lab tests and doctors’ fees.

Most of what Mr. Wilbon makes off with he can sell at only a fraction of the prescription cost. Heavy drinkers pay about 36 cents each for anti-ulcer pills that cost $1.66 each. The drug soothes upset stomachs. Crack smokers are willing to pay $2.00 to $3.00 for bronchial inhalers because they open up the lungs for larger doses of crack smoke. Inhalers cost taxpayers $20 each. Only syringes have a higher street price than prescription price; Mr. Wilbon can sell the 15 to 25 cent needles for as much as a dollar each.

Eventually, Medicaid will catch up with Mr. Wilbon and force him to restrict his visits to only one doctor. This is the system’s only way to control Medicaid thieves, but it is under attack because it “limits the choice” of recipients.

Mr. Wilbon, who lives in public housing, has six children and 16 grandchildren. “I don’t like to do real work,” he explains.

Give ’em Hell

The Justice Department has kindly set up a toll-free telephone line to solicit your views on how the department could be improved. There are any number of things you can advocate: deportation of illegal aliens, more border police, the addition of “Hispanic’ as a racial classification for criminals (so that crimes by Mexicans do not inflate the “white” crime rate), vigorous prosecution of the Crown Heights case (see below), or anything else that would help. Call early and often: (800) 546-3224.

Slow Progress

Attorney General Janet Reno has reluctantly decided to start the process of bringing federal civil rights charges against a black who was acquitted of stabbing a Jew to death, while friends chanted “Kill the Jew.” The killing took place in Brooklyn in 1991 during the Crown Heights riots. In a verdict that astonished most observers, the accused man was let off despite overwhelming evidence of guilt.

This federal trial — if there is one — will be much like that of the officers who beat Rodney King and were acquitted of most charges in a state trial. The feds leaped instantly into action that time, but it took tremendous political pressure from New York before Miss Reno would agree to investigate the Crown Heights case.

In another matter, New York City’s new mayor, Rudolph Giuliani, has announced that he is doing away with the city’s minority set-aside contracting program, which he called “indefensible as a constitutional matter.”

Money for Non-Whites

The federal Education Department has ruled that universities can discriminate on the basis of race when distributing scholarships even though the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination of this kind. The department ruled that discriminatory scholarships can be made to remedy past discrimination, but no findings of past discrimination need be made. It also ruled that race-based scholarships can be used to diversify the student body. This all just so much mumbo jumbo. Schools may discriminate against whites as much as they like.

| LETTERS FROM READERS |

|---|

Sir — The differences Prof. Levin expresses with me in the March issue are quite small. He interprets the results of the Scarr-Weinberg crossracial adoption study as indicating that 85 percent of the intelligence difference between blacks and whites is genetic, whereas I consider that the study shows that the black-white difference is 100 percent genetic. The main point on which we agree is that genetic factors are overwhelmingly the main reason for low black IQ and the associated disadvantages of poor education and low occupational. achievement, together with high rates of unemployment and crime.

Regarding the policy implications of this conclusion, Prof. Levin suggests that the first objective should be to convince the public that white racism is not responsible for low black achievement. I think that among serious social scientists this battle is already largely won. For instance, William Julius Wilson (The Tnily Disadvantaged, 1987) and Christopher Jencks (Rethinking Social Policy, 1992), both leading social scientists on the political left, have accepted that it is no longer possible to blame the social pathology of the black underclass on white racism. Prof. Jencks even recognizes that genes play some role, although he is still in need of education as to their importance. Nevertheless, I certainly agree with Prof. Levin that there is more work to be done hammering home the point that white racism cannot explain black underachievement.

My concern is that this could well take some years. Meanwhile, third world immigrants with low levels of intelligence are entering the United States at a rate of about one million a year. One of the major objectives of policy must be to alert the public to the damage this influx will inflict on the social fabric of America.

Richard Lynn, Coleraine, Northern Ireland

![]()

Sir — Congratulations on producing a magazine that deals directly with the race issue without taking a load of ideological baggage on board at the same time. All the best with your conference.

Your March issue addresses the subject of black and white IQs and cites further evidence that black IQs are on average lower than those of whites. In their heart of hearts, most people, white and black, know this. The problem lies not with the average black but with the white trend-setters who have drummed into blacks the idea that they are equal to whites.

Now that the damage has been done, blacks are not going to take kindly to the truth about IQ. Who can blame them? What can “soften the blow?” I think one thing that needs to be stressed is that intelligence is not everything. What about loyalty and love, for example? A street cleaner with an IQ of 95 is a more worthy member of society than a property shark with an IQ of 130. Nor is intelligence always something to be proud of; blacks need not be ashamed that their race was not smart enough to invent nuclear bombs.

Part of the anger and emotion aroused by the IQ issue can be defused by putting brains into perspective: They aren’t everything. Blacks do not suffer from white “racism” but they do suffer from the priority given to intelligence in Western society as the measure of a man or woman’s true worth.

Michael Walker, The Skorpion, Lutzowstrasse 39, 50674 Koln am Rhein, Germany

![]()

Sir — I am writing in response to Mr. Ostlund’s letter in the March issue. He calls the [Tom] Metzgers, [George Lincoln] Rockwells, and the KKK victims of “hysterical tunnel vision” and calls them “despicable.” I challenge the view that they are hysterical just because their writing is more vehement than that found in AR. They are trying to do something about America’s problems. What do AR readers do besides wring their hands?

Robert Briggs, Punta Gorda, Fla.

![]()

Sir — I read with interest your March review of The Rage of a Privileged Class. The author points out that many middle-class, apparently successful blacks burn with resentment against what they think is an unjust society. Many are wealthy and have benefited from affirmative action, but still seethe with racial resentment.

Let me call your attention to another book by a black man, Makes Me Wanna Holler. The author is a former armed robber who decided to reform himself and is now a newspaper reporter. He writes that when he visits the old neighborhoods where he used to be a criminal, he finds that young blacks are even more violently angry against white America than his generation was.

Is there not a lesson in these books? Are these men not telling us that despite years of legally enforced equal and even preferential treatment, blacks hate white America more than ever? There was much less resentment among blacks when they were treated as outright inferiors. The rise of black hatred only proves the folly of our policies. People will always resent you for giving them something they do not deserve. They will hate you if you then apologize because you did not give even more.

William English, Newport News, VA.