The Real Obama

F. Roger Devlin, American Renaissance, February 2009

Steve Sailer, America’s Half-Blood Prince: Barack Obama’s “Story of Race and Inheritance,” VDare.com, October 2008, 252 pp.

Who is Barack Obama? Despite the avalanche of reporting about him, Internet journalist Steve Sailer finds that virtually no one has bothered to read a key document about our next president that has been hiding in plain view since 1995: his own autobiography, Dreams from My Father. In America’s Half-Blood Prince — his first book — Mr. Sailer analyzes some of the remarkable things Mr. Obama reveals about himself.

First, Mr. Sailer finds much to admire in Mr. Obama’s writing, even calling him “a creative literary artist by nature, a politician by nurture,” and describes his prose as subtle, mellifluous and carefully-wrought. “His characters are vivid and he has an accurate ear for how different kinds of people speak,” writes Mr. Sailer.

None of this necessarily makes Dreams from My Father a pleasure to read. Mr. Sailer reports that the sentences are long and elaborate without always being clear, and the book’s “acres of self-pitying prose” can be eye-glazingly tedious. This, Mr. Sailer thinks, is the best refutation of rumors that the work was ghostwritten: “a professional hack would have insisted on punching it up with more funny stories and celebrity anecdotes.”

Mr. Obama’s fanatical commitment to the theme announced in his subtitle — race and inheritance — also dulls the book. Nothing is allowed to distract us from what he himself calls his “racial obsessions.” The man we meet in Dreams is no “race transcender” working to “bring people together,” as his campaign palaver would have us believe. He wallows in race, wholly absorbed in his own blackness. He speaks disapprovingly of a mixed-race classmate who declined to identify exclusively with his African side, and is preoccupied with proving himself “black enough.”

The source of this fixation, Mr. Sailer contends, was indoctrination by his white mother between his sixth and tenth years, the period during which they lived together in Indonesia with her second husband.

Stanley Ann Dunham (her father named her Stanley because he had wanted a boy) was a high school atheist, leftist and feminist smart enough to be offered admission to the University of Chicago when she was 15. However, she ended up attending the University of Hawaii where, shortly before her eighteenth birthday, she became pregnant by Barack Obama, Sr., a Kenyan student then 24. He was already married to a Kenyan woman, but she followed tribal custom and agreed that he should take a second wife. Stanley Ann was three months pregnant when she married her Kenyan lover. Two years later, he was offered two scholarships. One, to the New School for Social Research in New York, included an allowance for his wife and child. The other, to Harvard, would pay only for him. Viewing Harvard as more prestigious, he simply abandoned his family. He never paid a cent of child support, although he did visit his son for one month in 1971. He eventually fathered children by four women and died in an automobile accident in Kenya in 1982. He was drunk.

Obama’s mother soon took up with Lolo Soetoro, a “heroic-sounding anticolonialist Third Worlder with whom she imagined she could fulfill her dreams of making the world a better place.” His brothers had joined the Indonesian revolutionary army and been killed, he told her; the Dutch had burned down his family home. But now the Dutch were gone, a progressive, anti-American government was in power, and he would return to help build the new Indonesia.

Before Stanley Ann Obama could join her new husband in Jakarta, however, a coup d’état brought a pro-American right-wing government to power. Soon Lolo was contentedly working for Mobil Oil, and she came to despise him as a sellout to capitalism.

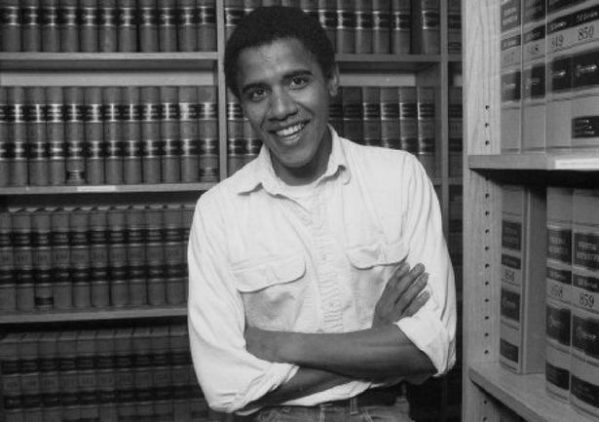

Barack Obama

She began teaching her young son how much finer a man his own father had been. Mr. Obama describes her telling him how his father “had grown up poor, in a poor country; his life had been hard, as hard as anything Lolo might have known. He hadn’t cut corners, though. He had led his life according to principles. I would follow his example, my mother decided.” “Your brains, your character, you got from him,” she told him.

Over time, writes Mr. Obama, “her message came to embrace black people generally. She would come home with books on the civil rights movement, the recordings of Mahalia Jackson, the speeches of Dr. King. She told me stories of schoolchildren in the South who were forced to read books handed down from wealthier white schools but who went on to become doctors and lawyers and scientists. To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.”

Mr. Sailer comments wryly that Mr. Obama’s mother sounds “like Obi-Wan Kenobi instructing Luke Skywalker in the glories of his Jedi Knight Heritage.” He summarizes her message to her impressionable son as “1) Being a politician, especially a politician who stands up for his race, is the highest calling in life, far superior to being some soulless corporate mercenary like her second husband; and 2) What blacks need is not more virtue, but better political leadership.”

Young Barry Obama — the name he went by until he decided to use the more alien Barack — fully believed his mother’s ludicrously inaccurate portrayal of his father: “The brilliant scholar, the generous friend, the upstanding leader — my father had been all those things.” He imagined Obama, Sr. standing over him, saying “you do not work hard enough, Barry. You must help in your people’s struggle.”

A reporter managed to track down some of Barry Obama’s Indonesian schoolmates, and learned that he had been badly treated because of his race: “He was teased more than any other kid in the neighborhood — primarily because he was so different in appearance.” He was sometimes attacked by three Indonesian kids at once, and on one occasion they threw him into a swamp. None of this is mentioned in Dreams from My Father; discrimination by Malays does not fit into Mr. Obama’s literally “black and white” worldview.

When he was ten, his mother sent young Barry back to Honolulu to live with his grandparents. About a year later, she left Lolo and took the daughter she had had with him back to Hawaii. Some time thereafter, she and the daughter returned to Indonesia — though not to Lolo — and again left Barry with his grandparents. She worked in various development-related jobs in Indonesia and died in 1995 of ovarian cancer.

We are particularly well informed about Mr. Obama’s years in Hawaii, Mr. Sailer writes, thanks to the many journalists who selflessly volunteered to spend the winter of 2007-8 on expense account in Hawaii hanging out with his old friends.

In Dreams, Obama’s Hawaiian years are portrayed as a long nightmare of racism. His ordeals included a curious fellow student asking to touch his kinky hair, a woman asking him if he played basketball (a racial stereotype, you see), and his grandmother’s fear of an aggressive black beggar. The beggar provided the basis for Mr. Obama’s notorious “throw grandma under the bus” speech of March 18, 2008, in which the candidate equated his grandmother’s entirely rational fear with Rev. Jeremiah Wright’s anti-white screeds.

Shortly after his grandmother told him about the beggar, a black friend explained to him that whites were right to fear black strangers: “that’s just how it is, so you might as well get used to it.” Mr. Obama’s reaction to this common-sense observation? “The earth shook under my feet, ready to crack open at any moment. I stopped, trying to steady myself, and knew for the first time that I was utterly alone.”

Much of the appeal of Mr. Obama’s depiction of himself as a victim of racism, notes Mr. Sailer, depends on readers’ ignorance about Hawaii. It is the most racially diverse state, and has the highest degree of racial mixing. Many residents are the product of several generations of mixed marriages. Such racial discrimination as occurs is often against whites. Mr. Sailer reports a “charming local custom of calling the last day of school ‘kill Haole day,’ on which white students are traditionally given beatings.” Such circumstances go unmentioned in Dreams from My Father, since they do not fit the story Mr. Obama wishes to fashion from his experiences.

Friends from Mr. Obama’s Hawaiian years have disputed the accuracy of Dreams. A black militant Mr. Obama called “Ray” turns out to be one Keith Kakugawa, half black and half Japanese. “[The book] makes me a very bitter person,” he complains; “I wasn’t that bitter.” Mr. Kakugawa also questions Obama’s portrayal of himself: “Barry’s biggest struggles then were missing his parents, his feelings of abandonment. The idea that his biggest struggle was race is bull.”

Barack Obama went on to attend Occidental College in California, trying to prove himself as a militant. “To avoid being mistaken for a sellout, I chose my friends carefully. The foreign students. The Chicanos. The Marxist professors and feminists and punk-rock performance poets. At night in the dorms we discussed neocolonialism, Franz Fanon, Eurocentrism and patriarchy.” After two years at Occidental, where he could not find enough “racism” with which to do heroic battle, he transferred to Columbia, on the edge of Harlem. A recurrent theme in Mr. Obama’s career, notes Mr. Sailer, is Power-to-the-People gestures with Ivy League outcomes.

During his senior year, Mr. Obama decided he would become a community organizer in the tradition of Saul Alinsky, but after graduating in 1983, he worked for a year to save money. In Dreams he describes himself as “a spy behind enemy lines” in “a consulting house to multinational corporations” where he hobnobbed with “Japanese financiers” and “German bond traders.” “I had my own office, my own secretary, money in the bank. As the months passed, I felt the idea of becoming an organizer slipping away from me.” A former colleague from those days has perceptively noted that Mr. Obama is retelling the story of the temptation of Christ: the world’s riches are offered to him, he wavers for a moment, and then “an angel calls, awakens his conscience, and helps him chose instead to fight for the people.” The reality, we learn, is that Obama was “a copy editor at a scruffy, low-paying newsletter shop.”

Mr. Obama says he had a white girlfriend while he was living in New York. Readers are free to make what they will of his account of how things ended, which Mr. Sailer quotes at length:

[O]ne weekend she invited me to her family’s country house. The parents were there, and they were very nice, very gracious . . . The family knew every inch of the land [and] the names of the earliest white settlers — their ancestors . . . The house was very old, her grandfather’s house. He had inherited it from his grandfather. The library was filled with old books and pictures of the grandfather with famous people he had known — presidents, diplomats, industrialists . . . Standing in that room, I realized that our two worlds, my friend’s and mine, were as distant from each other as Kenya is from Germany. And I knew that if we stayed together I’d eventually live in hers. Between the two of us, I was the one who knew how to live as an outsider.

I pushed her away. We started to fight . . . She couldn’t be black, she said. She would if she could, but she couldn’t. She could only be herself, and wasn’t that enough.

The Obama presidential campaign told us that Mr. Obama moved to Chicago to help unemployed steelworkers, conjuring up an image of beefy Catholic guys with names like Kowalski, but once again, his motives were racial. In Dreams, his Chicago job interviewer asks him “What do you know about Chicago, anyway?” He answers: “America’s most segregated city. A black man, Harold Washington, was just elected mayor, and white people don’t like it.” As Mr. Sailer explains, “after six years of looking, Obama had finally found a home where at least some whites reciprocated his antagonism.” Chicago was then the site of the “council wars” between Harold Washington and the white majority of city aldermen, the most blatant white vs. black conflict in the nation at the time.

As a community organizer, Obama’s job was to wring more tax money and government services from the city government for the black underclass. He never betrays the slightest suspicion that unearned money demoralized the blacks he was supposedly trying to help. His proudest achievement during these years was inducing the lazy Chicago Housing Authority bureaucrats to remove some asbestos from a housing project. As Mr. Sailer points out, “asbestos would fall comically low on any ranking of problems plaguing inner city African-Americans.”

Mr. Sailer does full justice to what he calls “that rip-snortin’ American comic character,” Rev. Jeremiah “God-damn-America” Wright. Mr. Wright is from the light-skinned black upper-middle class of Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood, which used to be notorious for snobbish standoffishness toward their darker brethren. To be invited to social events, girls had to pass the “paper bag test” — be at least as fair-toned as a brown paper bag. When black was proclaimed beautiful during the “Civil Rights” movement, Mr. Wright’s social set suffered an identity crisis.

“The most obvious thing about Wright has gone largely unnoticed,” writes Mr. Sailer, “like Obama, Wright has always had to deal with the question of whether he is black enough.” One way of resolving it was to take the lead in denouncing whites.

Mr. Wright therefore became a disciple of James Cone, a “theologian” who advocates worship of an exclusively black God. This God does not want his followers to turn the other cheek, commanding them instead “to destroy their oppressors by any means at their disposal.” Mr. Cone even presents the Almighty with an ultimatum: “Unless God is participating in this holy activity, we must reject God’s love.”

Mr. Wright outcompeted every other minister on the South Side of Chicago, building a black megachurch with 8,000 members. With his sermons denouncing white greed, he milked enough from this congregation to afford a Porsche and a huge house in a gated community whose residents are overwhelmingly white. He met his wife when a couple came seeking marriage counseling; he decided the solution was to take the woman for himself. More recently, he was reported to be involved in an adulterous affair with a married white woman.

Barack Obama chose this man carefully to be his “spiritual advisor.” His hesitations are recorded in Dreams, and all revolve around whether the Reverend was uncompromising enough about race.

This should be compared to Mr. Obama’s campaign brochures designed for the Bible Belt. There, the candidate solemnly declared that Mr. Wright “introduced me to someone named Jesus Christ. I learned that my sins could be redeemed. I learned that those things I was too weak to accomplish myself, He would accomplish with me if I placed my trust in Him,” etc., etc. This traditionally Christian, race-transcending Obama is not found anywhere in the 1995 autobiography.

Mr. Sailer believes Mr. Obama’s reorientation away from obsessive blackness followed his humiliating defeat by former Black Panther Bobby Rush in a 2000 bid for Congress. Some time afterwards, Mr. Obama came under the influence of political consultant David Axelrod. Mr. Axelrod specializes in “packaging black candidates for white electorates: he got Deval Patrick into the governorship of Massachusetts in 2006 using many of the same themes (and even some of the same words) as Barack Obama has used in his Presidential bid.” Apparently, Mr. Axelrod taught Mr. Obama that if he could only learn to make nice to white people, a far bigger prize than Illinois’ First District Congressional seat was within his grasp. Together, they came up with the “Half-Blood Prince” strategy of Mr. Obama running as a man born and bred to unite black and white. And the public bought it. Yet despite Mr. Obama’s apparent ideological shift, when Dreams from My Father was reissued in 2004, he told readers: “I cannot honestly say that I would tell the story much differently today than I did ten years ago.”

Now that Barack Obama is in the White House, will we be governed by the militantly black author of Dreams from My Father, or by the Axelrod-crafted, focus-group honed chameleon served up during the campaign? Will he be able to maintain his Chicano-Marxist-Franz Fanon contempt for America after it has laid so much power and adulation at his feet? The next four years will be the ultimate test of whether Mr. Obama really is “black enough.” There could be no more compelling lesson for whites than to discover that after all this country has done for him, Barack Obama is still the angry black man whose hatreds were honed in the church of Jeremiah Wright.