February 2009

| American Renaissance magazine | |

|---|---|

| Vol. 20, No. 2 | February 2009 |

| CONTENTS |

|---|

Morality and Abstract Thinking

The Real Obama

Racy Talk

O Tempora, O Mores!

Letters

| COVER STORY |

|---|

Morality and Abstract Thinking

How Africans may differ from Westerners

I am an American who taught philosophy in several African universities from 1976 to 1988, and have lived since that time in South Africa. When I first came to Africa, I knew virtually nothing about the continent or its people, but I began learning quickly. I noticed, for example, that Africans rarely kept promises and saw no need to apologize when they broke them. It was as if they were unaware they had done anything that called for an apology.

It took many years for me to understand why Africans behaved this way but I think I can now explain this and other behavior that characterizes Africa. I believe that morality requires abstract thinking — as does planning for the future — and that a relative deficiency in abstract thinking may explain many things that are typically African.

What follow are not scientific findings. There could be alternative explanations for what I have observed, but my conclusions are drawn from more than 30 years of living among Africans.

My first inklings about what may be a deficiency in abstract thinking came from what I began to learn about African languages. In a conversation with students in Nigeria I asked how you would say that a coconut is about halfway up the tree in their local language. “You can’t say that,” they explained. “All you can say is that it is ‘up’.” “How about right at the top?” “Nope; just ‘up’.” In other words, there appeared to be no way to express gradations.

A few years later, in Nairobi, I learned something else about African languages when two women expressed surprise at my English dictionary. “Isn’t English your language?” they asked. “Yes,” I said. “It’s my only language.” “Then why do you need a dictionary?”

They were puzzled that I needed a dictionary, and I was puzzled by their puzzlement. I explained that there are times when you hear a word you’re not sure about and so you look it up. “But if English is your language,” they asked, “how can there be words you don’t know?” “What?” I said. “No one knows all the words of his language.”

“But we know all the words of Kikuyu; every Kikuyu does,” they replied. I was even more surprised, but gradually it dawned on me that since their language is entirely oral, it exists only in the minds of Kikuyu speakers. Since there is a limit to what the human brain can retain, the overall size of the language remains more or less constant. A written language, on the other hand, existing as it does partly in the millions of pages of the written word, grows far beyond the capacity of anyone to know it in its entirety. But if the size of a language is limited, it follows that the number of concepts it contains will also be limited and hence that both language and thinking will be impoverished.

African languages were, of necessity, sufficient in their pre-colonial context. They are impoverished only by contrast to Western languages and in an Africa trying to emulate the West. While numerous dictionaries have been compiled between European and African languages, there are few dictionaries within a single African language, precisely because native speakers have no need for them. I did find a Zulu-Zulu dictionary, but it was a small-format paperback of 252 pages.

My queries into Zulu began when I rang the African Language Department at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and spoke to a white guy. Did “precision” exist in the Zulu language prior to European contact? “Oh,” he said, “that’s a very Eurocentric question!” and simply wouldn’t answer. I rang again, spoke to another white guy, and got a virtually identical response.

So I called the University of South Africa, a large correspondence university in Pretoria, and spoke to a young black guy. As has so often been my experience in Africa, we hit it off from the start. He understood my interest in Zulu and found my questions of great interest. He explained that the Zulu word for “precision” means “to make like a straight line.” Was this part of indigenous Zulu? No; this was added by the compilers of the dictionary.

But, he assured me, it was otherwise for “promise.” I was skeptical. How about “obligation?” We both had the same dictionary (English-Zulu, Zulu-English Dictionary, published by Witwatersrand University Press in 1958), and looked it up. The Zulu entry means “as if to bind one’s feet.” He said that was not indigenous but was added by the compilers. But if Zulu didn’t have the concept of obligation, how could it have the concept of a promise, since a promise is simply the oral undertaking of an obligation? I was interested in this, I said, because Africans often failed to keep promises and never apologized — as if this didn’t warrant an apology.

A light bulb seemed to go on in his mind. Yes, he said; in fact, the Zulu word for promise — isithembiso — is not the correct word. When a black person “promises” he means “maybe I will and maybe I won’t.” But, I said, this makes nonsense of promising, the very purpose of which is to bind one to a course of action. When one is not sure he can do something he may say, “I will try but I can’t promise.” He said he’d heard whites say that and had never understood it till now. As a young Romanian friend so aptly summed it up, when a black person “promises” he means “I’ll try.”

The failure to keep promises is therefore not a language problem. It is hard to believe that after living with whites for so long they would not learn the correct meaning, and it is too much of a coincidence that the same phenomenon is found in Nigeria, Kenya and Papua New Guinea, where I have also lived. It is much more likely that Africans generally lack the very concept and hence cannot give the word its correct meaning. This would seem to indicate some difference in intellectual capacity.

Note the Zulu entry for obligation: “as if to bind one’s feet.” An obligation binds you, but it does so morally, not physically. It is an abstract concept, which is why there is no word for it in Zulu. So what did the authors of the dictionary do? They took this abstract concept and made it concrete. Feet, rope, and tying are all tangible and observable, and therefore things all blacks will understand, whereas many will not understand what an obligation is. The fact that they had to define it in this way is, by itself, compelling evidence for my conclusion that Zulu thought has few abstract concepts and indirect evidence for the view that Africans may be deficient in abstract thinking.

Abstract thinking

Abstract entities do not exist in space or time; they are typically intangible and can’t be perceived by the senses. They are often things that do not exist. “What would happen if everyone threw rubbish everywhere?” refers to something we hope will not happen, but we can still think about it.

Everything we observe with our senses occurs in time and everything we see exists in space; yet we can perceive neither time nor space with our senses, but only with the mind. Precision is also abstract; while we can see and touch things made with precision, precision itself can only be perceived by the mind.

How do we acquire abstract concepts? Is it enough to make things with precision in order to have the concept of precision? Africans make excellent carvings, made with precision, so why isn’t the concept in their language? To have this concept we must not only do things with precision but must be aware of this phenomenon and then give it a name.

How, for example, do we acquire such concepts as belief and doubt? We all have beliefs; even animals do. When a dog wags its tail on hearing his master’s footsteps, it believes he is coming. But it has no concept of belief because it has no awareness that it has this belief and so no awareness of belief per se. In short, it has no self-consciousness, and thus is not aware of its own mental states.

It has long seemed to me that blacks tend to lack self-awareness. If such awareness is necessary for developing abstract concepts it is not surprising that African languages have so few abstract terms. A lack of self-awareness — or introspection — has advantages. In my experience neurotic behavior, characterized by excessive and unhealthy self-consciousness, is uncommon among blacks. I am also confident that sexual dysfunction, which is characterized by excessive self-consciousness, is less common among blacks than whites.

Time is another abstract concept with which Africans seem to have difficulties. I began to wonder about this in 1998. Several Africans drove up in a car and parked right in front of mine, blocking it. “Hey,” I said, “you can’t park here.” “Oh, are you about to leave?” they asked in a perfectly polite and friendly way. “No,” I said, “but I might later. Park over there” — and they did.

While the possibility that I might want to leave later was obvious to me, their thinking seemed to encompass only the here and now: “If you’re leaving right now we understand, but otherwise, what’s the problem?” I had other such encounters and the key question always seemed to be, “Are you leaving now?” The future, after all, does not exist. It will exist, but doesn’t exist now. People who have difficulty thinking of things that do not exist will ipso facto have difficulty thinking about the future.

It appears that the Zulu word for “future” — isikhati — is the same as the word for time, as well as for space. Realistically, this means that these concepts probably do not exist in Zulu thought. It also appears that there is no word for the past — meaning, the time preceding the present. The past did exist, but no longer exists. Hence, people who may have problems thinking of things that do not exist will have trouble thinking of the past as well as the future.

This has an obvious bearing on such sentiments as gratitude and loyalty, which I have long noticed are uncommon among Africans. We feel gratitude for things that happened in the past, but for those with little sense of the past such feelings are less likely to arise.

Why did it take me more than 20 years to notice all of this? I think it is because our assumptions about time are so deeply rooted that we are not even aware of making them and hence the possibility that others may not share them simply does not occur to us. And so we don’t see it, even when the evidence is staring us in the face.

Mathematics and maintenance

I quote from an article in the South African press about the problems blacks have with mathematics:

[Xhosa] is a language where polygon and plane have the same definition . . . where concepts like triangle, quadrilateral, pentagon, hexagon are defined by only one word. (“Finding New Languages for Maths and Science,” Star [Johannesburg], July 24, 2002, p. 8.)

More accurately, these concepts simply do not exist in Xhosa, which, along with Zulu, is one of the two most widely spoken languages in South Africa. In America, blacks are said to have a “tendency to approximate space, numbers and time instead of aiming for complete accuracy.” (Star, June 8, 1988, p.10.) In other words, they are also poor at math. Notice the identical triumvirate — space, numbers, and time. Is it just a coincidence that these three highly abstract concepts are the ones with which blacks — everywhere — seem to have such difficulties?

The entry in the Zulu dictionary for “number,” by the way — ningi — means “numerous,” which is not at all the same as the concept of number. It is clear, therefore, that there is no concept of number in Zulu.

White rule in South Africa ended in 1994. It was about ten years later that power outages began, which eventually reached crisis proportions. The principle reason for this is simply lack of maintenance on the generating equipment. Maintenance is future-oriented, and the Zulu entry in the dictionary for it is ondla, which means: “1. Nourish, rear; bring up; 2. Keep an eye on; watch (your crop).” In short, there is no such thing as maintenance in Zulu thought, and it would be hard to argue that this is wholly unrelated to the fact that when people throughout Africa say “nothing works,” it is only an exaggeration.

The New York Times reports that New York City is considering a plan (since implemented) aimed at getting blacks to “do well on standardized tests and to show up for class,” by paying them to do these things and that could “earn [them] as much as $500 a year.” Students would get money for regular school attendance, every book they read, doing well on tests, and sometimes just for taking them. Parents would be paid for “keeping a full-time job . . . having health insurance . . . and attending parent-teacher conferences.” (Jennifer Medina, “Schools Plan to Pay Cash for Marks,” New York Times, June 19, 2007.)

The clear implication is that blacks are not very motivated. Motivation involves thinking about the future and hence about things that do not exist. Given black deficiencies in this regard, it is not surprising that they would be lacking in motivation, and having to prod them in this way is further evidence for such a deficiency.

The Zulu entry for “motivate” is banga, under which we find “1. Make, cause, produce something unpleasant; . . . to cause trouble . . . . 2. Contend over a claim; . . . fight over inheritance; . . . 3. Make for, aim at, journey towards . . . .” Yet when I ask Africans what banga means, they have no idea. In fact, no Zulu word could refer to motivation for the simple reason that there is no such concept in Zulu; and if there is no such concept there cannot be a word for it. This helps explain the need to pay blacks to behave as if they were motivated.

The same New York Times article quotes Darwin Davis of the Urban League as “caution[ing] that the . . . money being offered [for attending class] was relatively paltry . . . and wondering . . . how many tests students would need to pass to buy the latest video game.”

Instead of being shamed by the very need for such a plan, this black activist complains that the payments aren’t enough! If he really is unaware how his remarks will strike most readers, he is morally obtuse, but his views may reflect a common understanding among blacks of what morality is: not something internalized but something others enforce from the outside. Hence his complaint that paying children to do things they should be motivated to do on their own is that they are not being paid enough.

In this context, I recall some remarkable discoveries by the late American linguist, William Stewart, who spent many years in Senegal studying local languages. Whereas Western cultures internalize norms — “Don’t do that!” for a child, eventually becomes “I mustn’t do that” for an adult — African cultures do not. They rely entirely on external controls on behavior from tribal elders and other sources of authority. When Africans were detribalized, these external constraints disappeared, and since there never were internal constraints, the results were crime, drugs, promiscuity, etc. Where there have been other forms of control — as in white-ruled South Africa, colonial Africa, or the segregated American South — this behavior was kept within tolerable limits. But when even these controls disappear there is often unbridled violence.

Stewart apparently never asked why African cultures did not internalize norms, that is, why they never developed moral consciousness, but it is unlikely that this was just a historical accident. More likely, it was the result of deficiencies in abstract thinking ability.

One explanation for this lack of abstract thinking, including the diminished understanding of time, is that Africans evolved in a climate where they could live day to day without having to think ahead. They never developed this ability because they had no need for it. Whites, on the other hand, evolved under circumstances in which they had to consider what would happen if they didn’t build stout houses and store enough fuel and food for the winter. For them it was sink or swim.

Surprising confirmation of Stewart’s ideas can be found in the May/June 2006 issue of the Boston Review, a typically liberal publication. In “Do the Right Thing: Cognitive Science’s Search for a Common Morality,” Rebecca Saxe distinguishes between “conventional” and “moral” rules. Conventional rules are supported by authorities but can be changed; moral rules, on the other hand, are not based on conventional authority and are not subject to change. “Even three-year-old children . . . distinguish between moral and conventional transgressions,” she writes. The only exception, according to James Blair of the National Institutes of Health, are psychopaths, who exhibit “persistent aggressive behavior.” For them, all rules are based only on external authority, in whose absence “anything is permissible.” The conclusion drawn from this is that “healthy individuals in all cultures respect the distinction between conventional . . . and moral [rules].”

However, in the same article, another anthropologist argues that “the special status of moral rules cannot be part of human nature, but is . . . just . . . an artifact of Western values.” Anita Jacobson-Widding, writing of her experiences among the Manyika of Zimbabwe, says:

I tried to find a word that would correspond to the English concept of ‘morality.’ I explained what I meant by asking my informants to describe the norms for good behavior toward other people. The answer was unanimous. The word for this was tsika. But when I asked my bilingual informants to translate tsika into English, they said that it was ‘good manners’ . . .

She concluded that because good manners are clearly conventional rather than moral rules, the Manyika simply did not have a concept of morality. But how would one explain this absence? Miss Jacobson-Widding’s explanation is the typical nonsense that could come only from a so-called intellectual: “the concept of morality does not exist.” The far more likely explanation is that the concept of morality, while otherwise universal, is enfeebled in cultures that have a deficiency in abstract thinking.

According to now-discredited folk wisdom, blacks are “children in adult bodies,” but there may be some foundation to this view. The average African adult has the raw IQ score of the average 11-year-old white child. This is about the age at which white children begin to internalize morality and no longer need such strong external enforcers.

Gruesome cruelty

Another aspect of African behavior that liberals do their best to ignore but that nevertheless requires an explanation is gratuitous cruelty. A reviewer of Driving South, a 1993 book by David Robbins, writes:

A Cape social worker sees elements that revel in violence . . . It’s like a cult which has embraced a lot of people who otherwise appear normal. . . . At the slightest provocation their blood-lust is aroused. And then they want to see death, and they jeer and mock at the suffering involved, especially the suffering of a slow and agonizing death. (Citizen [Johannesburg], July 12, 1993, p.6.)

There is something so unspeakably vile about this, something so beyond depravity, that the human brain recoils. This is not merely the absence of human empathy, but the positive enjoyment of human suffering, all the more so when it is “slow and agonizing.” Can you imagine jeering at and mocking someone in such horrible agony?

During the apartheid era, black activists used to kill traitors and enemies by “necklacing” them. An old tire was put around the victim’s neck, filled with gasoline, and — but it is best to let an eye-witness describe what happened next:

The petrol-filled tyre is jammed on your shoulders and a lighter is placed within reach . . . . Your fingers are broken, needles are pushed up your nose and you are tortured until you put the lighter to the petrol yourself. (Citizen; “SA’s New Nazis,” August 10, 1993, p.18.)

The author of an article in the Chicago Tribune, describing the equally gruesome way the Hutu killed Tutsi in the Burundi massacres, marveled at “the ecstasy of killing, the lust for blood; this is the most horrible thought. It’s beyond my reach.” (“Hutu Killers Danced In Blood Of Victims, Videotapes Show,” Chicago Tribune, September 14, 1995, p.8.) The lack of any moral sense is further evidenced by their having videotaped their crimes, “apparently want[ing] to record . . . [them] for posterity.” Unlike Nazi war criminals, who hid their deeds, these people apparently took pride in their work.

In 1993, Amy Biehl, a 26-year-old American on a Fulbright scholarship, was living in South Africa, where she spent most of her time in black townships helping blacks. One day when she was driving three African friends home, young blacks stopped the car, dragged her out, and killed her because she was white. A retired senior South African judge, Rex van Schalkwyk, in his 1998 book One Miracle is Not Enough, quotes from a newspaper report on the trial of her killers: “Supporters of the three men accused of murdering [her] . . . burst out laughing in the public gallery of the Supreme Court today when a witness told how the battered woman groaned in pain.” This behavior, Van Schalkwyk wrote, “is impossible to explain in terms accessible to rational minds.” (pp. 188-89.)

These incidents and the responses they evoke — “the human brain recoils,” “beyond my reach,” “impossible to explain to rational minds” — represent a pattern of behavior and thinking that cannot be wished away, and offer additional support for my claim that Africans are deficient in moral consciousness.

I have long suspected that the idea of rape is not the same in Africa as elsewhere, and now I find confirmation of this in Newsweek:

According to a three-year study [in Johannesburg] . . . more than half of the young people interviewed — both male and female — believe that forcing sex with someone you know does not constitute sexual violence . . . [T]he casual manner in which South African teens discuss coercive relationships and unprotected sex is staggering. (Tom Masland, “Breaking The Silence,” Newsweek, July 9, 2000.)

Clearly, many blacks do not think rape is anything to be ashamed of.

The Newsweek author is puzzled by widespread behavior that is known to lead to AIDS, asking “Why has the safe-sex effort failed so abjectly?” Well, aside from their profoundly different attitudes towards sex and violence and their heightened libido, a major factor could be their diminished concept of time and reduced ability to think ahead.

Nevertheless, I was still surprised by what I found in the Zulu dictionary. The main entry for rape reads: “1. Act hurriedly; . . . 2. Be greedy. 3. Rob, plunder, . . . take [possessions] by force.” While these entries may be related to our concept of rape, there is one small problem: there is no reference to sexual intercourse! In a male-dominated culture, where saying “no” is often not an option (as confirmed by the study just mentioned), “taking sex by force” is not really part of the African mental calculus. Rape clearly has a moral dimension, but perhaps not to Africans. To the extent they do not consider coerced sex to be wrong, then, by our conception, they cannot consider it rape because rape is wrong. If such behavior isn’t wrong it isn’t rape.

An article about gang rape in the left-wing British paper, the Guardian, confirms this when it quotes a young black woman: “The thing is, they [black men] don’t see it as rape, as us being forced. They just see it as pleasure for them.” (Rose George, “They Don’t See it as Rape. They Just See it as Pleasure for Them,” June 5, 2004.) A similar attitude seems to be shared among some American blacks who casually refer to gang rape as “running a train.” (Nathan McCall, Makes Me Wanna Holler, Vintage Books, 1995.)

If the African understanding of rape is far afield, so may be their idea of romance or love. I recently watched a South African television program about having sex for money. Of the several women in the audience who spoke up, not a single one questioned the morality of this behavior. Indeed, one plaintively asked, “Why else would I have sex with a man?”

From the casual way in which Africans throw around the word “love,” I suspect their understanding of it is, at best, childish. I suspect the notion is alien to Africans, and I would be surprised if things are very different among American blacks. Africans hear whites speak of “love” and try to give it a meaning from within their own conceptual repertoire. The result is a child’s conception of this deepest of human emotions, probably similar to their misunderstanding of the nature of a promise.

I recently located a document that was dictated to me by a young African woman in June 1993. She called it her “story,” and the final paragraph is a poignant illustration of what to Europeans would seem to be a limited understanding of love:

On my way from school, I met a boy. And he proposed me. His name was Mokone. He tell me that he love me. And then I tell him I will give him his answer next week. At night I was crazy about him. I was always thinking about him.

Moral blindness

Whenever I taught ethics I used the example of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French Army who was convicted of treason in 1894 even though the authorities knew he was innocent. Admitting their mistake, it was said, would have a disastrous effect on military morale and would cause great social unrest. I would in turn argue that certain things are intrinsically wrong and not just because of their consequences. Even if the results of freeing Dreyfus would be much worse than keeping him in prison, he must be freed, because it is unjust to keep an innocent man in prison.

To my amazement, an entire class in Kenya said without hesitation that he should not be freed. Call me dense if you want, but it was 20 years before the full significance of this began to dawn on me.

Africans, I believe, may generally lack the concepts of subjunctivity and counterfactuality. Subjunctivity is conveyed in such statements as, “What would you have done if I hadn’t showed up?” This is contrary to fact because I did show up, and it is now impossible for me not to have shown up. We are asking someone to imagine what he would have done if something that didn’t happen (and now couldn’t happen) had happened. This requires self-consciousness, and I have already described blacks’ possible deficiency in this respect. It is obvious that animals, for example, cannot think counterfactually, because of their complete lack of self-awareness.

When someone I know tried to persuade his African workers to contribute to a health insurance policy, they asked “What’s it for?” “Well, if you have an accident, it would pay for the hospital.” Their response was immediate: “But boss, we didn’t have an accident!” “Yes, but what if you did?” Reply? “We didn’t have an accident!” End of story.

Interestingly, blacks do plan for funerals, for although an accident is only a risk, death is a certainty. (The Zulu entries for “risk” are “danger” and “a slippery surface.”) Given the frequent all-or-nothing nature of black thinking, if it’s not certain you will have an accident, then you will not have an accident. Furthermore, death is concrete and observable: We see people grow old and die. Africans tend to be aware of time when it is manifested in the concrete and observable.

One of the pivotal ideas underpinning morality is the Golden Rule: do unto others as you would have them do unto you. “How would you feel if someone stole everything you owned? Well, that’s how he would feel if you robbed him.” The subjunctivity here is obvious. But if Africans may generally lack this concept, they will have difficulty in understanding the Golden Rule and, to that extent, in understanding morality.

If this is true we might also expect their capacity for human empathy to be diminished, and this is suggested in the examples cited above. After all, how do we empathize? When we hear about things like “necklacing” we instinctively — and unconsciously — think: “How would I feel if I were that person?” Of course I am not and cannot be that person, but to imagine being that person gives us valuable moral “information:” that we wouldn’t want this to happen to us and so we shouldn’t want it to happen to others. To the extent people are deficient in such abstract thinking, they will be deficient in moral understanding and hence in human empathy — which is what we tend to find in Africans.

In his 1990 book Devil’s Night, Ze’ev Chafets quotes a black woman speaking about the problems of Detroit: “I know some people won’t like this, but whenever you get a whole lot of black people, you’re gonna have problems. Blacks are ignorant and rude.” (pp. 76-77.)

If some Africans cannot clearly imagine what their own rude behavior feels like to others — in other words, if they cannot put themselves in the other person’s shoes — they will be incapable of understanding what rudeness is. For them, what we call rude may be normal and therefore, from their perspective, not really rude. Africans may therefore not be offended by behavior we would consider rude — not keeping appointments, for example. One might even conjecture that African cruelty is not the same as white cruelty, since Africans may not be fully aware of the nature of their behavior, whereas such awareness is an essential part of “real” cruelty.

I am hardly the only one to notice this obliviousness to others that sometimes characterizes black behavior. Walt Harrington, a white liberal married to a light-skinned black, makes some surprising admissions in his 1994 book, Crossings: A White Man’s Journey Into Black America:

I notice a small car . . . in the distance. Suddenly . . . a bag of garbage flies out its window . . . . I think, I’ll bet they’re blacks. Over the years I’ve noticed more blacks littering than whites. I hate to admit this because it is a prejudice. But as I pass the car, I see that my reflex was correct — [they are blacks].

[As I pull] into a McDonald’s drive-through . . . [I see that] the car in front of me had four black[s] in it. Again . . . my mind made its unconscious calculation: We’ll be sitting here forever while these people decide what to order. I literally shook my head. . . . My God, my kids are half black! But then the kicker: we waited and waited and waited. Each of the four . . . leaned out the window and ordered individually. The order was changed several times. We sat and sat, and I again shook my head, this time at the conundrum that is race in America.

I knew that the buried sentiment that had made me predict this disorganization . . . was . . . racist. . . . But my prediction was right. (pp. 234-35.)

Africans also tend to litter. To understand this we must ask why whites don’t litter, at least not as much. We ask ourselves: “What would happen if everyone threw rubbish everywhere? It would be a mess. So you shouldn’t do it!” Blacks’ possible deficiency in abstract thinking makes such reasoning more difficult, so any behavior requiring such thinking is less likely to develop in their cultures. Even after living for generations in societies where such thinking is commonplace, many may still fail to absorb it.

It should go without saying that my observations about Africans are generalizations. I am not saying that none has the capacity for abstract thought or moral understanding. I am speaking of tendencies and averages, which leave room for many exceptions.

To what extent do my observations about Africans apply to American blacks? American blacks have an average IQ of 85, which is a full 15 points higher than the African average of 70. The capacity for abstract thought is unquestionably correlated with intelligence, and so we can expect American blacks generally to exceed Africans in these respects.

Still, American blacks show many of the traits so striking among Africans: low mathematical ability, diminished abstract reasoning, high crime rates, a short time-horizon, rudeness, littering, etc. If I had lived only among American blacks and not among Africans, I might never have reached the conclusions I have, but the more extreme behavior among Africans makes it easier to perceive the same tendencies among American blacks.

Gedhalia Braun holds a PhD in philosophy and is the author of Racism, Guilt, Self-Hatred and Self-Deceit.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

The Real Obama

Black militant or ‘race transcender’

Steve Sailer, America’s Half-Blood Prince: Barack Obama’s “Story of Race and Inheritance,” VDare.com, October 2008, 252 pp.

Who is Barack Obama? Despite the avalanche of reporting about him, Internet journalist Steve Sailer finds that virtually no one has bothered to read a key document about our next president that has been hiding in plain view since 1995: his own autobiography, Dreams from My Father. In America’s Half-Blood Prince — his first book — Mr. Sailer analyzes some of the remarkable things Mr. Obama reveals about himself.

First, Mr. Sailer finds much to admire in Mr. Obama’s writing, even calling him “a creative literary artist by nature, a politician by nurture,” and describes his prose as subtle, mellifluous and carefully-wrought. “His characters are vivid and he has an accurate ear for how different kinds of people speak,” writes Mr. Sailer.

None of this necessarily makes Dreams from My Father a pleasure to read. Mr. Sailer reports that the sentences are long and elaborate without always being clear, and the book’s “acres of self-pitying prose” can be eye-glazingly tedious. This, Mr. Sailer thinks, is the best refutation of rumors that the work was ghostwritten: “a professional hack would have insisted on punching it up with more funny stories and celebrity anecdotes.”

Mr. Obama’s fanatical commitment to the theme announced in his subtitle — race and inheritance — also dulls the book. Nothing is allowed to distract us from what he himself calls his “racial obsessions.” The man we meet in Dreams is no “race transcender” working to “bring people together,” as his campaign palaver would have us believe. He wallows in race, wholly absorbed in his own blackness. He speaks disapprovingly of a mixed-race classmate who declined to identify exclusively with his African side, and is preoccupied with proving himself “black enough.”

The source of this fixation, Mr. Sailer contends, was indoctrination by his white mother between his sixth and tenth years, the period during which they lived together in Indonesia with her second husband.

Stanley Ann Dunham (her father named her Stanley because he had wanted a boy) was a high school atheist, leftist and feminist smart enough to be offered admission to the University of Chicago when she was 15. However, she ended up attending the University of Hawaii where, shortly before her eighteenth birthday, she became pregnant by Barack Obama, Sr., a Kenyan student then 24. He was already married to a Kenyan woman, but she followed tribal custom and agreed that he should take a second wife. Stanley Ann was three months pregnant when she married her Kenyan lover. Two years later, he was offered two scholarships. One, to the New School for Social Research in New York, included an allowance for his wife and child. The other, to Harvard, would pay only for him. Viewing Harvard as more prestigious, he simply abandoned his family. He never paid a cent of child support, although he did visit his son for one month in 1971. He eventually fathered children by four women and died in an automobile accident in Kenya in 1982. He was drunk.

Obama’s mother soon took up with Lolo Soetoro, a “heroic-sounding anticolonialist Third Worlder with whom she imagined she could fulfill her dreams of making the world a better place.” His brothers had joined the Indonesian revolutionary army and been killed, he told her; the Dutch had burned down his family home. But now the Dutch were gone, a progressive, anti-American government was in power, and he would return to help build the new Indonesia.

Before Stanley Ann Obama could join her new husband in Jakarta, however, a coup d’état brought a pro-American right-wing government to power. Soon Lolo was contentedly working for Mobil Oil, and she came to despise him as a sellout to capitalism.

She began teaching her young son how much finer a man his own father had been. Mr. Obama describes her telling him how his father “had grown up poor, in a poor country; his life had been hard, as hard as anything Lolo might have known. He hadn’t cut corners, though. He had led his life according to principles. I would follow his example, my mother decided.” “Your brains, your character, you got from him,” she told him.

Over time, writes Mr. Obama, “her message came to embrace black people generally. She would come home with books on the civil rights movement, the recordings of Mahalia Jackson, the speeches of Dr. King. She told me stories of schoolchildren in the South who were forced to read books handed down from wealthier white schools but who went on to become doctors and lawyers and scientists. To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.”

Mr. Sailer comments wryly that Mr. Obama’s mother sounds “like Obi-Wan Kenobi instructing Luke Skywalker in the glories of his Jedi Knight Heritage.” He summarizes her message to her impressionable son as “1) Being a politician, especially a politician who stands up for his race, is the highest calling in life, far superior to being some soulless corporate mercenary like her second husband; and 2) What blacks need is not more virtue, but better political leadership.”

Young Barry Obama — the name he went by until he decided to use the more alien Barack — fully believed his mother’s ludicrously inaccurate portrayal of his father: “The brilliant scholar, the generous friend, the upstanding leader — my father had been all those things.” He imagined Obama, Sr. standing over him, saying “you do not work hard enough, Barry. You must help in your people’s struggle.”

A reporter managed to track down some of Barry Obama’s Indonesian schoolmates, and learned that he had been badly treated because of his race: “He was teased more than any other kid in the neighborhood — primarily because he was so different in appearance.” He was sometimes attacked by three Indonesian kids at once, and on one occasion they threw him into a swamp. None of this is mentioned in Dreams from My Father; discrimination by Malays does not fit into Mr. Obama’s literally “black and white” worldview.

When he was ten, his mother sent young Barry back to Honolulu to live with his grandparents. About a year later, she left Lolo and took the daughter she had had with him back to Hawaii. Some time thereafter, she and the daughter returned to Indonesia — though not to Lolo — and again left Barry with his grandparents. She worked in various development-related jobs in Indonesia and died in 1995 of ovarian cancer.

We are particularly well informed about Mr. Obama’s years in Hawaii, Mr. Sailer writes, thanks to the many journalists who selflessly volunteered to spend the winter of 2007-8 on expense account in Hawaii hanging out with his old friends.

In Dreams, Obama’s Hawaiian years are portrayed as a long nightmare of racism. His ordeals included a curious fellow student asking to touch his kinky hair, a woman asking him if he played basketball (a racial stereotype, you see), and his grandmother’s fear of an aggressive black beggar. The beggar provided the basis for Mr. Obama’s notorious “throw grandma under the bus” speech of March 18, 2008, in which the candidate equated his grandmother’s entirely rational fear with Rev. Jeremiah Wright’s anti-white screeds.

Shortly after his grandmother told him about the beggar, a black friend explained to him that whites were right to fear black strangers: “that’s just how it is, so you might as well get used to it.” Mr. Obama’s reaction to this common-sense observation? “The earth shook under my feet, ready to crack open at any moment. I stopped, trying to steady myself, and knew for the first time that I was utterly alone.”

Much of the appeal of Mr. Obama’s depiction of himself as a victim of racism, notes Mr. Sailer, depends on readers’ ignorance about Hawaii. It is the most racially diverse state, and has the highest degree of racial mixing. Many residents are the product of several generations of mixed marriages. Such racial discrimination as occurs is often against whites. Mr. Sailer reports a “charming local custom of calling the last day of school ‘kill Haole day,’ on which white students are traditionally given beatings.” Such circumstances go unmentioned in Dreams from My Father, since they do not fit the story Mr. Obama wishes to fashion from his experiences.

Friends from Mr. Obama’s Hawaiian years have disputed the accuracy of Dreams. A black militant Mr. Obama called “Ray” turns out to be one Keith Kakugawa, half black and half Japanese. “[The book] makes me a very bitter person,” he complains; “I wasn’t that bitter.” Mr. Kakugawa also questions Obama’s portrayal of himself: “Barry’s biggest struggles then were missing his parents, his feelings of abandonment. The idea that his biggest struggle was race is bull.”

Barack Obama went on to attend Occidental College in California, trying to prove himself as a militant. “To avoid being mistaken for a sellout, I chose my friends carefully. The foreign students. The Chicanos. The Marxist professors and feminists and punk-rock performance poets. At night in the dorms we discussed neocolonialism, Franz Fanon, Eurocentrism and patriarchy.” After two years at Occidental, where he could not find enough “racism” with which to do heroic battle, he transferred to Columbia, on the edge of Harlem. A recurrent theme in Mr. Obama’s career, notes Mr. Sailer, is Power-to-the-People gestures with Ivy League outcomes.

During his senior year, Mr. Obama decided he would become a community organizer in the tradition of Saul Alinsky, but after graduating in 1983, he worked for a year to save money. In Dreams he describes himself as “a spy behind enemy lines” in “a consulting house to multinational corporations” where he hobnobbed with “Japanese financiers” and “German bond traders.” “I had my own office, my own secretary, money in the bank. As the months passed, I felt the idea of becoming an organizer slipping away from me.” A former colleague from those days has perceptively noted that Mr. Obama is retelling the story of the temptation of Christ: the world’s riches are offered to him, he wavers for a moment, and then “an angel calls, awakens his conscience, and helps him chose instead to fight for the people.” The reality, we learn, is that Obama was “a copy editor at a scruffy, low-paying newsletter shop.”

Mr. Obama says he had a white girlfriend while he was living in New York. Readers are free to make what they will of his account of how things ended, which Mr. Sailer quotes at length:

[O]ne weekend she invited me to her family’s country house. The parents were there, and they were very nice, very gracious . . . The family knew every inch of the land [and] the names of the earliest white settlers — their ancestors . . . The house was very old, her grandfather’s house. He had inherited it from his grandfather. The library was filled with old books and pictures of the grandfather with famous people he had known — presidents, diplomats, industrialists . . . Standing in that room, I realized that our two worlds, my friend’s and mine, were as distant from each other as Kenya is from Germany. And I knew that if we stayed together I’d eventually live in hers. Between the two of us, I was the one who knew how to live as an outsider.

I pushed her away. We started to fight . . . She couldn’t be black, she said. She would if she could, but she couldn’t. She could only be herself, and wasn’t that enough.

The Obama presidential campaign told us that Mr. Obama moved to Chicago to help unemployed steelworkers, conjuring up an image of beefy Catholic guys with names like Kowalski, but once again, his motives were racial. In Dreams, his Chicago job interviewer asks him “What do you know about Chicago, anyway?” He answers: “America’s most segregated city. A black man, Harold Washington, was just elected mayor, and white people don’t like it.” As Mr. Sailer explains, “after six years of looking, Obama had finally found a home where at least some whites reciprocated his antagonism.” Chicago was then the site of the “council wars” between Harold Washington and the white majority of city aldermen, the most blatant white vs. black conflict in the nation at the time.

As a community organizer, Obama’s job was to wring more tax money and government services from the city government for the black underclass. He never betrays the slightest suspicion that unearned money demoralized the blacks he was supposedly trying to help. His proudest achievement during these years was inducing the lazy Chicago Housing Authority bureaucrats to remove some asbestos from a housing project. As Mr. Sailer points out, “asbestos would fall comically low on any ranking of problems plaguing inner city African-Americans.”

Mr. Sailer does full justice to what he calls “that rip-snortin’ American comic character,” Rev. Jeremiah “God-damn-America” Wright. Mr. Wright is from the light-skinned black upper-middle class of Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood, which used to be notorious for snobbish standoffishness toward their darker brethren. To be invited to social events, girls had to pass the “paper bag test” — be at least as fair-toned as a brown paper bag. When black was proclaimed beautiful during the “Civil Rights” movement, Mr. Wright’s social set suffered an identity crisis.

“The most obvious thing about Wright has gone largely unnoticed,” writes Mr. Sailer, “like Obama, Wright has always had to deal with the question of whether he is black enough.” One way of resolving it was to take the lead in denouncing whites.

Mr. Wright therefore became a disciple of James Cone, a “theologian” who advocates worship of an exclusively black God. This God does not want his followers to turn the other cheek, commanding them instead “to destroy their oppressors by any means at their disposal.” Mr. Cone even presents the Almighty with an ultimatum: “Unless God is participating in this holy activity, we must reject God’s love.”

Mr. Wright outcompeted every other minister on the South Side of Chicago, building a black megachurch with 8,000 members. With his sermons denouncing white greed, he milked enough from this congregation to afford a Porsche and a huge house in a gated community whose residents are overwhelmingly white. He met his wife when a couple came seeking marriage counseling; he decided the solution was to take the woman for himself. More recently, he was reported to be involved in an adulterous affair with a married white woman.

Barack Obama chose this man carefully to be his “spiritual advisor.” His hesitations are recorded in Dreams, and all revolve around whether the Reverend was uncompromising enough about race.

This should be compared to Mr. Obama’s campaign brochures designed for the Bible Belt. There, the candidate solemnly declared that Mr. Wright “introduced me to someone named Jesus Christ. I learned that my sins could be redeemed. I learned that those things I was too weak to accomplish myself, He would accomplish with me if I placed my trust in Him,” etc., etc. This traditionally Christian, race-transcending Obama is not found anywhere in the 1995 autobiography.

Mr. Sailer believes Mr. Obama’s reorientation away from obsessive blackness followed his humiliating defeat by former Black Panther Bobby Rush in a 2000 bid for Congress. Some time afterwards, Mr. Obama came under the influence of political consultant David Axelrod. Mr. Axelrod specializes in “packaging black candidates for white electorates: he got Deval Patrick into the governorship of Massachusetts in 2006 using many of the same themes (and even some of the same words) as Barack Obama has used in his Presidential bid.” Apparently, Mr. Axelrod taught Mr. Obama that if he could only learn to make nice to white people, a far bigger prize than Illinois’ First District Congressional seat was within his grasp. Together, they came up with the “Half-Blood Prince” strategy of Mr. Obama running as a man born and bred to unite black and white. And the public bought it. Yet despite Mr. Obama’s apparent ideological shift, when Dreams from My Father was reissued in 2004, he told readers: “I cannot honestly say that I would tell the story much differently today than I did ten years ago.”

Now that Barack Obama is in the White House, will we be governed by the militantly black author of Dreams from My Father, or by the Axelrod-crafted, focus-group honed chameleon served up during the campaign? Will he be able to maintain his Chicano-Marxist-Franz Fanon contempt for America after it has laid so much power and adulation at his feet? The next four years will be the ultimate test of whether Mr. Obama really is “black enough.” There could be no more compelling lesson for whites than to discover that after all this country has done for him, Barack Obama is still the angry black man whose hatreds were honed in the church of Jeremiah Wright.

F. Roger Devlin, PhD, is the author of Alexandre Kojève and the Outcome of Modern Thought.

| ARTICLE |

|---|

Racy Talk

An illuminating look at racism’s true believers.

“A Conversation About Race,” written, produced, and directed by Craig Bodeker, New Century Productions, 2008, black & white, 58 minutes, $20.00 (DVD).

In March 2008, Barack Obama gave a speech meant to defuse the controversy about Jeremiah Wright, his anti-white pastor of 20 years. “Racism,” he said, is the key to understanding America. He complained that the country has ignored the problem for far too long and that it was time to confront racial divisions in order to “perfect our union.”

“A Conversation About Race” is a brilliant, film-documentary response to Mr. Obama’s invitation to confront racial divisions, and it is with the many Americans who agree with Mr. Obama — “the believers” — with whom filmmaker Craig Bodeker has a conversation. He advertised for people in the Denver area who were willing to appear in a documentary about “ending racism now,” and also did man-on-the-street interviews.

There was no shortage of eager participants; he spoke to 50 people on camera, including whites, blacks, Hispanics and Asians. All were believers. In his introduction to the interviews, Mr. Bodeker explains that he did not set out to make the subjects look foolish but that “the conventional wisdom on racism is so convoluted today that sometimes it’s unavoidable.”

Mr. Bodeker begins his interviews by asking each subject if he sees racism is his daily life. All say yes; they see racism “every day,” “a lot,” or “all the time,” and the whites see it as much as the non-whites. After establishing that “racism” is everywhere, Mr. Bodeker asks, “What is racism?” This is where his subjects first begin to stumble. None can give a good definition of racism. It is “chopping ourselves into categories,” “police harassing the homeless,” and “ignorance, a lack of knowledge.” It is “racial profiling, why we have so many men of color in prison.” It is “economic class.” It is fascinating to watch people who are earnest and well-spoken — for the most part the interview subjects are surprisingly articulate and are sincerely attempting to answer the questions — flail about.

The believers flail a lot. Mr. Bodeker offers a dictionary definition of racism as “the belief in the superiority of one race over another,” and then asks his subjects to describe specific instances of racism they’ve seen. A dapper black man named Martin claims he experienced racism at a public library, when librarians stared at him when he entered, asked if he needed help when he didn’t, and said goodbye to him when he left. He says the “goodbye” really meant “good-riddance.” Paul, a rough-looking black man with dreadlocks, a wild goatee, and crooked teeth says it is racism when a woman he passes on the street shifts her purse to the other arm. A young black woman sees racism when a non-black co-worker says, “Yes, I understand what you’re saying.” She seems to think that what this really means is that she has been understood even though she is black. One black man, after having agreed that racism is everywhere, cannot give a single example of it.

A middle-aged white woman, Mary Ann, believes she is racist because she notices black people in her all-white neighborhood. A white coed named Tina says she is racist for noticing that blacks on public transportation sometimes make a lot of noise. No one comes close to giving an example of a belief in racial superiority.

Young Tina appears on camera several times, consistently parroting the believer catechism and even apologizing for being brought up in “this white culture, this racist culture.” All white believers express varying degrees of self-reproach. It is one of the most striking aspects of the film: non-whites are resentful; whites feel guilty.

Mr. Bodeker cleverly brings up the question of racial superiority by asking if blacks are better than whites at basketball. They all agree, with many of the blacks appearing to take pride in athletic superiority. When Mr. Bodeker asks if whites are better than blacks at anything, the believers seem offended. When he suggests whites are better than blacks at standardized tests, the believers have a standard answer: It is because whites cheated by making tests that are culturally biased in their favor.

There is desperate flailing when Mr. Bodeker asks why Asians do better than whites on culturally-biased “white” tests. No one is willing to say it is because Asians are smarter than whites, because that would suggest whites are smarter than blacks. The look on poor Tina’s face as she struggles with this conundrum is priceless.

Mr. Bodeker asks the subjects to name a racist public figure. None can, so he suggests Jesse Jackson. Mary Ann, the middle-aged white woman who lives in the all-white neighborhood, doesn’t think Mr. Jackson is a racist. He is, she says, just an “advocate for black people.” When asked if she can name an advocate for white people, she fumbles, looks embarrassed, and goes silent.

Most of the interview subjects admit that blacks commit more crime than whites. Blacks are especially ready to admit this, and to agree that some blacks try to intimidate whites. Interestingly, blacks do not offer “racism” as an excuse for high crime rates, but whites do. Many come close to saying that racism justifies black crime, that it is retaliation for white oppression.

Blacks are also far more sensible about immigration than whites. Nearly all want less immigration, with several calling for immediate deportation of all illegals. Not one white says that immigration should be cut, and Mary Ann says that since immigrants are poor they should all be let in.

The whites in the film have clearly lost all racial feeling. Several suggest that it will be a good thing when whites become a minority, and some believe the solution to racism will be the elimination of whites through miscegenation. Mary Ann, however, concedes that “white nationalists” might mourn the disappearance of whites. Overall, the whites act like members of a vanquished tribe, meekly acquiescing to their displacement.

At the end of the film, Mr. Bodeker concludes that what passes for “racism” in America is nothing more than an effort to instill collective guilt in whites. Whites are supposed to be indifferent to themselves as a race. If they are not indifferent, they can only be supremacists, and for a believer, white supremacy is the worst possible crime. Mr. Bodeker should know because he tells us he used to be a believer, thanks to the propaganda he was fed in elementary school.

This is an excellent film, especially when one considers that it is Mr. Bodeker’s first attempt. The production values are high, with crisp camera work and a very subtle musical score. It is skillfully, even artfully, edited. The running time is under an hour, and it never loses the viewer’s attention. Mr. Bodeker provides the narration and from time to time addresses the viewer in cutaways from the interviews. He has a pleasant voice and an appealing personality.

With his faded jeans, long hair and stubbly chin, Craig Bodeker looks like a typical liberal. He certainly does not look like a man who would make a documentary that deftly exposes liberal myths. Yet that is precisely what Mr. Bodeker has done, and he has done it both entertainingly and effectively.

“A Conversation About Race” is good enough and thoughtful enough to run on PBS but, of course, it never will. Instead, it would make a perfect gift for a friend or family member who could do with a gentle nudge in the direction of common sense.

Note: New Century Productions is not affiliated with New Century Foundation, which publishes American Renaissance. The similarity in names is coincidental.

| IN THE NEWS |

|---|

O Tempora, O Mores!

Sub-replacement Fertility

Women who did not want children but still felt a maternal urge used to make do with houseplants or a cat, but now, thanks to a company called Reborn, they can experience the joys of motherhood without the bother of pregnancy, childbirth, or even midnight feedings. Reborn sells life-like infant dolls for prices ranging from $100 to several thousand dollars, and business is booming.

Forty-nine-year-old Linda is married with no children of her own, but with a Reborn in her arms she can now feel like a mother. “It’s not a crazy habit, like, you know, drinking, or some sort of, something that’s going to hurt you,” she explains. “It’s like a hobby and it doesn’t really hurt anybody.” Lachelle Moore, who has real children and grandchildren, has a clutch of fakes as well. “What’s so wonderful about Reborns is that they’re forever babies. There’s no college tuition, no dirty diapers . . . just the good part of motherhood,” she says. Mrs. Moore even throws birthday parties for her dolls and other women take them to the park or out to restaurants. Psychologists say all this is harmless unless women “stop interacting socially with others.” [Adult Women Play House With Fake Babies, ABC-7 News (Washington, DC), Jan. 2, 2009.]

The Company He Kept

One of Martin Luther King’s advisers was a black Baptist preacher named James Luther Bevel, who died in December. A prominent leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the New York Times remembered Bevel as “charismatic and eloquently quick-witted in a vernacular style” and noted, more reservedly, that he was “a man of passion and peculiarity.” Historian Taylor Branch described him more vividly: “a wild man from Itta Bena, Mississippi. . . . A self-described example of the legendary ‘chicken-eating, liquor-drinking, woman-chasing Baptist preacher.’ ”

Bevel is credited with turning King against the war in Vietnam War, which Bevel believed was an act of racist imperialism. Bevel was also at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis the day King was shot, and went to his grave insisting that James Earl Ray did not pull the trigger. Bevel claimed he had proof of Ray’s innocence — which he never produced — and even offered to represent him in court, though he was not a lawyer. By 1970, Bevel had become something of a prophet to a group of disciples who were students at Spelman College, the black girls’ school in Atlanta. After he forced some of them to drink his urine as a loyalty test, the SCLC expelled him. During the 1980s, Bevel supported Ronald Reagan and ran for Congress in Illinois as a Republican. He eventually switched allegiance to perpetual fringe presidential candidate Lyndon LaRouche, and even served as his running mate in 1992.

In April 2008, a Virginia jury convicted Bevel of incest after one of his daughters claimed he forced her to have sex with him in the 1990s (Virginia has no statute of limitations for incest). Three other daughters also accused Bevel of molesting them and it came out in court that Bevel had fathered 16 children by 7 women. In October, a judge sentenced Bevel to 15 years in prison, but he was released in November, shortly before he died, because of pancreatic cancer. [Bruce Weber, James L. Bevel, 72, An Adviser to Dr. King, New York Times, Dec. 23, 2008.]

Detroit’s public school district is $400 million in the red and no longer has the money to buy basic supplies. The principal of one elementary school, Academy of the Americas, recently sent a letter asking parents and staff to donate items “that are of the utmost importance for proper school functioning and most importantly for student health and safety,” such as toilet paper, paper towels, trash bags, and 60, 100 or 150-watt light bulbs. This is not the first time Principal Naomi Khalil has rattled the tin cup. At the beginning of the academic year she asked for pencils, pens, and Kleenex. [Detroit School Lacks Toilet Paper, Light Bulbs, ClickOnDetroit.com, Jan. 7, 2009.]

Felipe Fernandez-Armesto is a British historian of Spanish descent who teaches at Tufts University in Massachusetts. Before the election, Mr. Fernandez-Armesto wrote an article predicting an easy Obama victory, but said he could work up no enthusiasm for Mr. Obama because his policies would differ little from those of John McCain. His article is interesting only because of the following sentences:

“I have not been in the US long enough to be hypocritical about race. The hypocrisy is especially strong in the university sector, where color-blindness policies are a mask for positive discrimination. We are not allowed to know the race of job applicants, but we search the CVs for clues to candidates who will boost our department’s racial diversity statistics.” [Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, Obama’s Promise is Global, Times Higher Education, Oct. 2, 2008.]

Scouting Hispanics

The Boy Scouts are America’s largest youth organization, with 2.8 million members, but membership peaked in 1972 and is now down by half. Scandals and bad publicity cut the rolls, and many boys prefer video games to camping, but the biggest challenge is demographic. Scouting is overwhelmingly white, and there are a lot more non-white children now than in 1972. Twenty percent of children under 18 are Hispanic — double the figure in 1980 — and another 15 percent are black. Just 57 percent are white.

“We either are going to figure out how to make Scouting the most exciting, dynamic organization for Hispanic kids, or we’re going to be out of business,” says Rick Cronk, former national president of the Boy Scouts, and chairman of the World Scout Committee. Today, only three percent of Scouts are Hispanic, and Mr. Cronk wants to double that figure by 2010, when the Boy Scouts celebrate their centennial. He says earlier attempts to recruit Hispanics with soccer and Spanish brochures have largely failed because “we knew very little about the Hispanic family, how they see us, what they value.”

The Boy Scouts have hired a PR firm that specializes in marketing to Hispanics and is making a pitch to immigrant parents in six heavily Hispanic cities from Fresno, California to Orlando, Florida. They will run commercials on Spanish radio and television stations, and hire more Spanish-speaking staff. “We’re serious about this,” says Rob Mazzuca, Chief Scout Executive. “This is a reinventing of the Boy Scouts of America.”

Julio Cammarota, a University of Arizona professor who studies Hispanics says the Scouts will have to change if they want to appeal to Hispanics. What has to go? The focus on individual achievement and camping in the woods. “They’d be better off starting with a carne asada (barbecue) in a city park,” he says. “Sending their kids away on their own, that’s not familiar [to Hispanic parents]. ”[Boy Scouts See Hispanics As Key to Boosting Ranks, AP, Dec. 26, 2008.]

Lowering the Boone

Back in 1968, Disney Studios drew a cartoon figure for the University of Denver, whose athletic teams are called Pioneers. The figure is a pudgy, bearded mountain man who wears a coonskin cap. The character became known as “Denver Boone” or just “Boone.” Boone was fired as mascot in 1998 when the university became uncomfortable with his “lack of gender inclusiveness,” and students and alumni have been trying to bring him back ever since. A survey conducted in 2008 showed 87 percent wanted him reinstated, but the university’s History and Traditions Task Force announced that would never happen because Boone represents “an era of Western imperialism” and is “offensive” to women and non-whites.

Student body president Monica Kumar hailed the decision. “The name ‘Boone’ is linked to Daniel Boone, and to people of Native American ancestry, it’s sensitive because he was part of a movement that pushed Native Americans to the side,” she says. “We are a university that has been very sensitive to diversity and one of our objectives is to be inclusive. And this was an opportunity for us to come together and show our inclusiveness.” Chancellor Robert Coombe agrees. “The old Boone figure is one that does not reflect the broad diversity of the DU community and is not an image that many of today’s women, persons of color, international students and faculty and others can easily relate to as defining the pioneering spirit,” he says. [Valerie Richardson, Denver Axes Mascot ‘Boone’ in Diversity Drive, Washington Times, Dec. 27, 2008.]

Quis Custodiet?

Growing up on the Texas side of the Rio Grande, Edward Caballero feared the Border Patrol, even though he is a natural-born citizen. “It seems like most Border Patrol officers were Anglos, and I hate to say it, not too friendly towards Hispanics,” he explains, adding, “It’s not so much that way anymore.” Mr. Caballero should know. He is one of the Border Patrol’s new Hispanic agents. In just two years, as a result of the Bush administration’s efforts to expand and diversify the force, the number of Hispanic agents has grown from 6,400 in 2006 to 9,300 today, an increase of 45 percent. More than half — 52 percent — of Border Patrol agents are now Hispanic. Recruiters say Hispanics are a natural fit. They speak Spanish, which is required of all agents, and many are familiar with the job.

Critics see the obvious problems: Hispanic agents, especially if they have family on the other side of the border, will be tempted to go easy on illegals, and drug cartels are likely to infiltrate a Hispanic force. There is already no shortage of miscreant Hispanic agents. In December, prosecutors indicted Agent Leonel Morales for taking a $9,000 bribe to escort a load of drugs across the border. Just before Christmas, a federal judge sentenced former Border Patrol Agent Reynaldo Zuniga to seven years in prison for smuggling cocaine. [James Pinkerton, Hispanics Bolster Border Patrol, Houston Chronicle, Dec. 29, 2008.]

Shortly after the election, Democratic Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid of Nevada spoke to reporters about the top priorities of the new Congress that will meet in January. Here is what he had to say about amnesty:

Q: With more Democrats in the Senate and the House and a Democrat in the White House, how do you see congressional efforts playing out on such issues as health care and immigration?

A: On immigration, there’s been an agreement between (President-elect Barack) Obama and (Arizona Republican Sen. John) McCain to move forward on that. . . .

Q: Will there be as much of a fight on immigration as last time?

A: We’ve got McCain and we’ve got a few others. I don’t expect much of a fight at all. [Deborah Barfield Berry, Reid Says Democrats to Tackle Big Issues, Gannett News Service, Nov. 23, 2008.]

We’ll prove him wrong.

Un-neighborly Behavior

Antioch, California, is a mostly white city of 100,000 about 40 miles northwest of San Francisco. When the housing market slowed a few years ago, many Antioch landlords began accepting Section 8 tenants. Section 8 is the federal housing program that subsidizes rent for poor people. Desperate landlords like it because they get a steady income and tax breaks. Poor people like Section 8 because they can live in pricier neighborhoods. Federal bureaucrats like Section 8 because it “de-concentrates” poverty. The only people who don’t like it are the neighbors.

In Antioch, most of the people getting vouchers were black, and from 2000 to 2007, as more landlords got Section 8 tenants, Antioch’s black population doubled to more than 16,000. Crime went up, and residents began complaining about “loud parties, mean pit bulls, blaring car radios, prostitution, drug dealing, and muggings of schoolchildren.” Police got so many complaints about Section 8 renters that in 2006 they formed a special unit to deal with them. “In some neighborhoods, it was complete madness,” says longtime resident David Gilbert, a black retired man who organized a community watch.

Under federal law, Section 8 renters can be booted from subsidized housing if they commit crimes. Antioch police weren’t shy about filing for eviction, and 70 percent of filings were against blacks. Now several blacks are suing the city, accusing police of “discrimination” and of trying to drive them out. They have asked a federal judge to make their case a class-action suit on behalf of hundreds of other black renters. “A lot of people are moving out here looking for a better place to live,” says plaintiff Karen Coleman. “We are trying to raise our kids like everyone else. But they don’t want us here.”

The situation in Antioch is “hotter than elsewhere,” according to a spokesman for the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, but most cities with an influx of Section 8 renters have the same problems. Many activists and academics deny that Section 8 brings crime to the suburbs. Susan Popkin, of the Urban Institute, is one of them, but concedes that Section 8 causes problems. “That can be a recipe for anxiety,” she says. “It can really change the demographics of a neighborhood.” [Paul Elias, Influx of Black Renters Raises Tension in Bay Area, AP, Dec. 30, 2008.]

| LETTERS FROM READERS |

|---|

Sir — Benjamin J. Ryan is to be congratulated on his excellent article exposing Martin Luther King’s radical views and unbecoming personal conduct. It is a disgrace that none of these facts is out in the open. However, I believe we should focus more on his sympathy for racial preferences, black power, and reparations — despite his “content of their character” rhetoric — rather than his personal failings.

From the 1950s until the 1980s, when they decided to make him one of their own, conservatives opposed King because of his Communist connections, his reliance on civil disobedience, and his violation of States’ Rights principles. They ignored his primary message of integration. Every American should know that King was a pervert, plagiarist, and Communist sympathizer. But at the end of the day, the main reason we need to oppose King and his deification is his “color blind” propaganda that from the very beginning was applied selectively to whites.

Ellison Lodge, Fairfax, Va.

Sir — “The Machine Was Racist” in the January “O Tempora” section brought back an unforgettable memory. Back in the ’60s, I sold office machines, including a hand-held voice recorder. We had an inquiry from Bell Telephone about the recorder, so I took one over for a demo. I was sent to the third floor, where I met a black man, who was the head of some department. We shook hands and I demonstrated the handset — recording and playback. He wanted me to explain how the machine worked, so I repeated the demo. He then called for a stenographer to take notes, while I demonstrated the handset yet again.

The man said he wanted to try the machine before buying it, so I handed it over. There was a three-position control button on the side of the handset — record, re-wind, and stop — and another button for playback. He must have pushed the wrong buttons because he got no results. I demonstrated the machine again, handed it to him, and again he got no results.

Then he dropped the bomb: He told me that the reason it did not work for him, was that the electronics inside were not programmed to record black voices. I looked over at the secretary, and she looked out the window, avoiding eye contact. I assured the man no such thing was possible. He finally made the machine work, and asked the secretary to put through the purchase order. An eye-opening experience? You bet!

Dale E. Lauffer, Columbus, Ohio

Sir — I write in praise of Rüdiger Halder’s “What Happened in Austria” in the December issue. This is precisely the type of article we need in AR. I believe Mr. Halder is correct when he says that the best hope for our people lies with the small nations of Europe. Homogeneity is the key. It seems likely that the politics of the future will not be national, or even racial, but tribal. Regionalism might have a future in the US after all, with the Scots-Irish ruling Appalachia and the Hispanics the Southwest.

Robert Briggs, Sarasota, Fla.

Sir — This is a response to Gregory Hood’s “Ron Paul Was Never the Answer” in the December issue. I am a race realist who supports Ron Paul. Dr. Paul is an intelligent, principled man who thoroughly understands the subjects he advocates. He writes his own material and needs no ghost writer. His main strength is that he is not a professional politician, but a citizen who happens to hold office. Above all else, Dr. Paul is committed to the defense of liberty. What other politician can make that claim?

Ed Zeman, Auburn, Ala.

Sir — I will read Erectus Walks Amongst Us on the strength of Jared Taylor’s review in the January issue. The book appears to be a remarkable combination of erudition and race-realist common sense. It is a pity books like this cannot find mainstream publishers.

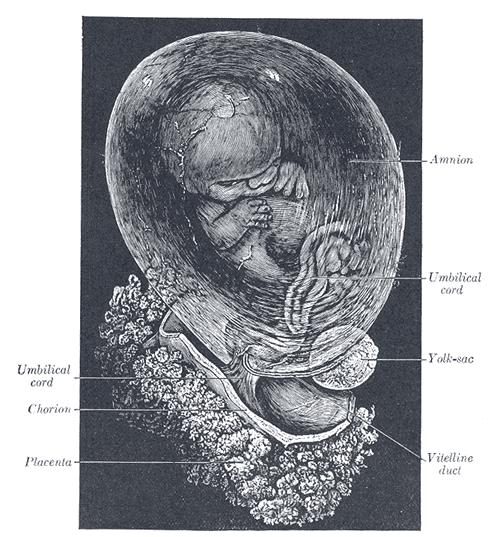

However, I take issue with one of the illustrations in the review: an artist’s conception of Neanderthal Man. National Geographic has been commissioning detailed reconstructions that it claims are more realistic. The attached photo is of a reconstruction of a woman. She is rough trade, to be sure, but looks much less like a werewolf than the snaggle-toothed chap you ran in the January issue.

Sarah Wentworth, Richmond, Va.

Sir — In his book Erectus Walks Amongst Us, Richard Fuerle writes that the races separated three million years ago rather than just 150,000 years ago. That is a huge difference. Doesn’t Mr. Taylor have the competence or courage to take a position.

Charles Quentin, Sacramento, Calif.

You must enable Javascript in your browser.