Justice for Zimmerman

Wilburn Sprayberry, American Renaissance, December 20, 2013

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

Jack Cashill, ‘If I Had a Son’: Race, Guns, and the Railroading of George Zimmerman, WND Books, 317 pages, $25.95.

In this remarkable book about the Trayvon Martin/George Zimmerman case, investigative reporter Jack Cashill recounts one of the most recent and dismal instances of the railroading of an innocent man who, though obviously Hispanic, was considered white enough to be portrayed as a racist killer. Even those who followed the events closely will learn a great deal from this book about what could have been a grotesque injustice.

Mr. Cashill also takes a sharp-eyed look at what he calls the Black Grievance Industry (BGI). He explains how long-time “race hustlers” such as Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton, politicians such as Eric Holder and Barack Obama, intellectuals such as Harvard’s Henry Louis Gates, and less well-known media figures such as Washington Post columnist Jonathan Capehart have become arbiters of what we are allowed to say in the “national conversation on race.” Increasingly, this tilts the scales of justice.

Mr. Cashill also describes the white politicians, bureaucrats, lawyers, and media people who collaborate with the BGI and help it pervert justice. He explains how collusion between the BGI and its white collaborators in the cases of Tawana Brawley, Rodney King, O.J. Simpson, the Duke rape hoax, the Pigford settlement, and others have sparked riots, let murderers to go free, destroyed the reputations of the innocent, and bilked the government out of billions of dollars.

Mr. Cashill points out that “blacks commit interracial muggings, robberies, and rapes at thirty-five times the rate of whites,” and explains that this is a legitimate reason to profile by race. He also scorns the media’s refusal to publicize, much less reflect on, the statistics of black pathology.

But the heart of the book is the Zimmerman case. Mr. Cashill begins with a meticulous recounting of events during the rainy night of February 26, 2012 in a burglary- and drug-plagued neighborhood — inaccurately described by the media as upscale and majority white — in Sanford, Florida. Mr. Zimmerman, a neighborhood crime-watch volunteer, called police on his cell-phone to report a hooded figure he thought was behaving suspiciously. After Trayvon Martin realized he was being watched, he first ran away but came back, knocked Mr. Zimmerman to the ground, jumped on top of his chest, and pounded him “MMA [mixed martial arts] style.”

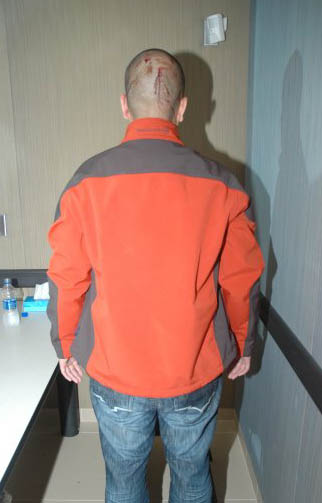

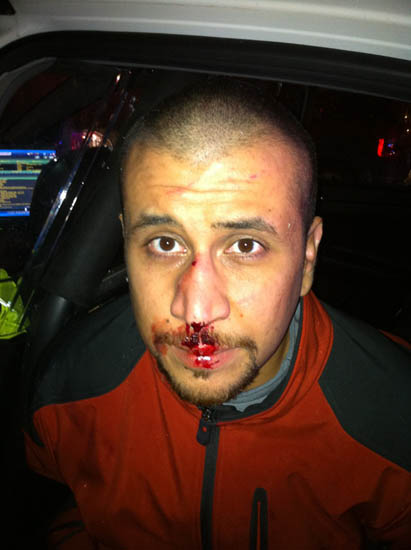

The only eyewitness to the encounter reported that Mr. Zimmerman screamed for help. Feeling his life was in danger, Mr. Zimmerman managed to draw his legally licensed pistol and shoot his assailant once. The police he had called arrived minutes later. They took Mr. Zimmerman to the police station, where he passed a lie-detector test. The police observed his broken nose and bloody head lacerations, talked to witnesses, concluded that he had acted in self defense, and released him.

What apparently set the BGI in motion on this case was the reaction of Trayvon’s father, Tracy Martin, to an interview with a police investigator, Chris Serino. Mr. Serino expressed great sympathy over the death of Mr. Martin’s son, and told him he would interview Mr. Zimmerman again, “to catch him in a lie.” This probably gave Tracy Martin the impression the police did not believe Mr. Zimmerman’s account.

In the second interview, police told Mr. Zimmerman there was a video of the altercation. This was a falsehood designed to rattle Mr. Zimmerman and detect if he was hiding something. Instead, Mr. Zimmerman was relieved, saying “I prayed to God someone videotaped it.” Detective Serino later provided key testimony during the trial and admitted he believed Mr. Zimmerman’s version of events.

Tracy Martin, however, was soon saying that Zimmerman stalked and killed his son, only because Mr. Zimmerman was white and Trayvon was black. This was the version sold to the media by “Team Trayvon,” a gaggle of lawyers and PR experts led by Benjamin Crump, a black lawyer experienced in shaking down the establishment. Along with the implied threat of violence if Mr. Zimmerman was not put on trial, they sold the same story to Florida state prosecutors.

Mr. Cashill explains:

Crump understood that the national media were suckers for a story with a racial angle, specifically one that featured a black victim of white injustice. He also suspected that if enough national pressure could be brought to bear, the local authorities would crack [and indict Mr. Zimmerman]. After meeting with Crump . . . [white PR man Ryan] Julison immediately began pitching the Trayvon case to the larger world.

“Pitching the Trayvon case” meant controlling the media images of the protagonists, right from the first press conference:

On that fateful March 7 day, either through reckless indifference to facts or a conscious effort to suppress them, Team Trayvon chose to introduce George Zimmerman to the world as a thuggish white man, a loose cannon, an armed vigilante who preyed on undersized black children. To make this story line work, Crump and his associates also had to scrub Martin’s background and package him as something that he was not, an innocent little boy. They would have remarkable success doing both.

Team Trayvon succeeded in portraying Zimmerman as white, despite his own self-description as Hispanic, and his mestizo appearance. Mr. Cashill wryly notes that after being raised largely by his Peruvian mother and grandmother, and learning Spanish before he learned English, “Zimmerman has more claim to being ‘Hispanic’ than white-raised President Barack Obama has to being ‘black.’ ”

The characterization of Mr. Zimmerman was helped by New York Times reporter Lizette Alvarez, who conveniently invented the term “white Hispanic” for Mr. Zimmerman, which prompted his father’s exasperated observation that for the media, “George must be kept white . . . somehow.” The media repeatedly ran the one photo of Mr. Zimmerman that made him look threatening: a 2005 mug shot from a minor incident with police that was mostly based on a misunderstanding and led to no charges. They distorted and exaggerated anything negative in his background, and ignored his record of community service, and mentoring “at risk” black youngsters in the Big Brother program. These tactics worked especially well with what Mr. Cashill calls the “low information slice” of TV viewers.

Team Trayvon was just as successful in crafting an image of “Zimmerman’s victim.” The media obliged by repeatedly publishing a photo of a younger, smaller, happier Trayvon, far different from the troubled, foul-mouthed teenager he had become by the night of February 26th. At age 17, Trayvon was four inches taller than Mr. Zimmerman and had a physique similar to that of the boxer Thomas “Hit-man” Hearns at about the age when Mr. Hearns won his first professional fight.

“Pitching the Trayvon case” also meant controlling the evidence of what happened that night and how it was presented to the media. This meant ignoring the eyewitness account of Trayvon’s attack and Mr. Zimmerman’s bloody injuries.

For Tracy Martin, it also meant changing his story. When neighbors called 911, a voice crying for help in the background was recorded along with the conversation. Initially, Tracy Martin told police the voice was not Trayvon’s. Belatedly realizing this undermined his position, he told a national television audience that the voice was Trayvon’s. It didn’t matter to the media that Mr. Zimmerman’s entire family had said from the beginning that the voice was George’s, or that the eye-witness both heard and saw Zimmerman screaming.

The media also made things up. CNN decided that Mr. Zimmerman had used the word “coon” to describe Trayvon during his recorded call to police. “Coon” was actually a burst of static. Even some conservative media accepted the BGI version. Rich Lowry of National Review headlined a column, “Shocker! Sharpton is right for once.” Other National Review writers joined in condemning Mr. Zimmerman.

Mr. Cashill also explains how the anti-gun lobby saw an opportunity to launch a campaign against licenses to carry and Stand Your Ground laws. Linking shooter-of-children and the media’s most hated man, George Zimmerman, to the media’s most hated organization, produced this astonishing headline in the New York Daily News: “Shame on the NRA and its Newest Poster Child, George Zimmerman.” The campaign went nowhere. Statistics showed that Florida’s license-to-carry law resulted in a decline in violent crime, and the Florida governor’s review panel determined that Stand Your Ground was a success, and had not created a “shoot first and ask questions later” atmosphere, as the media claimed.

Meanwhile, Team Trayvon and the BGI put pressure on the state of Florida. The superstars of race hustling descended on Sanford to do what they do best: television. “Old grievance bulls” Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson jostled with more junior BGI members such as NAACP president Ben Jealous for time on news programs, where their demand was always the same: arrest Zimmerman now. The threat of black violence was always present. And on March 23, President Barack Obama announced that “if I had a son, he would look like Trayvon.”

As Benjamin Crump predicted, the state cracked. Lacking evidence for legal probable cause to arrest Mr. Zimmerman, the BGI and media had created political probable cause. The state of Florida had, it seemed, joined Team Trayvon. On April 11, Special Prosecutor Angela Corey indicted Mr. Zimmerman for second-degree murder in a theatrical, nationally televised press conference with Trayvon’s parents at her side. Zimmerman turned himself in. As Mr. Cashill notes, Angela Corey — up for re-election as State Attorney for the 4th Florida Judicial Circuit — had her “Great White Defendant,” the term made famous in Tom Wolfe’s novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities:

The opportunity to align oneself with the remnants of the civil rights movement has left many a Republican giddy. Corey [a Republican] was no exception . . . Zimmerman may not have been exactly white, but he was white enough, and she, Angela Corey, was on the side of the angels, the side of “sweet parents” and the “precious victim” and the Team Trayvon attorneys whom she chose to “especially thank.”

The indictment was the high point for the pro-Martin forces. The very next day, celebrity defense lawyer Alan Dershowitz ridiculed the indictment on national television, calling it so weak the judge should throw it out.

But there had been resistance on the Internet before Mr. Dershowitz. Mr. Cashill describes how one group of bloggers at The Conservative Treehouse became suspicious of the media embrace of Team Trayvon. They began digging up whatever they could find on the case, sometimes using the Freedom of Information Act, and even hitting the streets to ferret out facts. As Mr. Cashill notes:

By trial time, this obscure little blog had become information central in “Florida v. Zimmerman.” Florida had on its side the US Justice Department, the president of the United States, the BGI, the entertainment industry, and the mainstream media. Zimmerman had on his side two folksy local lawyers and their aides, an army of bloggers, and most importantly, the truth.

Around the time the “Treepers” became active, a few isolated stories began appearing in newspapers such as the The Miami Herald, in which Trayvon Martin did not appear as a sweet, innocent child, but a juvenile delinquent, with school suspensions for marijuana possession and suspicion of burglary. His social media postings revealed a thug who called himself “No_Limit_Nigga,” bragged about his fighting prowess, and hinted that he was selling drugs.

Thanks to the work of The Conservative Treehouse and televised eviscerations of the state’s indictment by legal experts, by the time the trial began 14 months later, enough facts had been publicized to justify considerable sympathy for Mr. Zimmerman. Right-wing talk radio and Fox News began to take up his cause. George Zimmerman even briefly come out of hiding — there were death threats against him and his family — to tell his side of the story on Sean Hannity’s program.

As for the trial, Mr. Cashill calls the prosecution’s opening statement an “F-bombing” of the all-female jury. Several times, Assistant DA John Guy repeated Mr. Zimmerman’s complaint during his call to the policed dispatcher that the “fucking punks” who burgle the complex always get away. Mr. Cashill notes that the prosecution’s entire case was based mostly on “scare words:”

[DA John Guy] compensated for a lack of tangible evidence with dramatic incantations of words like “profiled” and “chased” and “semi-automatic” as though these very words proved a hateful intent on Zimmerman’s part.

As those who watched the trial recall, the prosecution’s case started to collapse with its first witness and never recovered. Mr. Cashill assigns much of the credit to Mr. Zimmerman’s lawyers, Mark O’Mara and Don West, for a defense that stuck to the facts, politely but effectively questioning the credibility or relevance of some prosecution witnesses, and refuted claims that Mr. Zimmerman lied, was angry, or was a wannabe cop. But part of the jury’s not-guilty verdict was based simply on the fact that the prosecution had no case. George Zimmerman acted in self-defense against a brutal physical attack.

In summing up the case, Mr. Cashill makes a number of observations:

- If the jury had not been sequestered it might well have reached a guilty verdict because of pressure from the BGI through the media and through other ways — including direct intimidation.

- A jury with more blacks instead of just one black Hispanic would probably have behaved like the 75-percent black O.J. Simpson jury, ignoring the evidence and voting to please the BGI. Or it might have deadlocked, leading to a new trial, with possibly more black jurors.

- It is conceivable that the prosecution threw the case intentionally, “over charging” Mr. Zimmerman with an unprovable second-degree murder charge to ensure acquittal, and seating a mostly white jury. They may have tried the case only because of pressure from the Black Grievance Industry and for fear of black violence if Mr. Zimmerman were not tried.

- If not for the “alternative media” of the internet, the old-style elite media of television networks and newspapers would have created such a hostile environment that a fair trial for Zimmerman would have been impossible.

- In the end, though race was not part of the jury’s verdict, the case was all about one word: white. Making George Zimmerman white made the case fit the Team Trayvon and BGI story. If Mr. Zimmerman had been identified as Hispanic, there would have been no controversy, no media circus, no arrest, and no trial.

The author does not say so, but most of what happened in this case really wasn’t about Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman. It was about sending a message to white people: Know your place.

Mr. Cashill’s background — he has written for the Wall Street Journal, the Weekly Standard, and similar publications — would not suggest he is a race realist. However, he has written a very racially realistic book, and although it is only implied, If I Had a Son has an important message for white people: wake up!