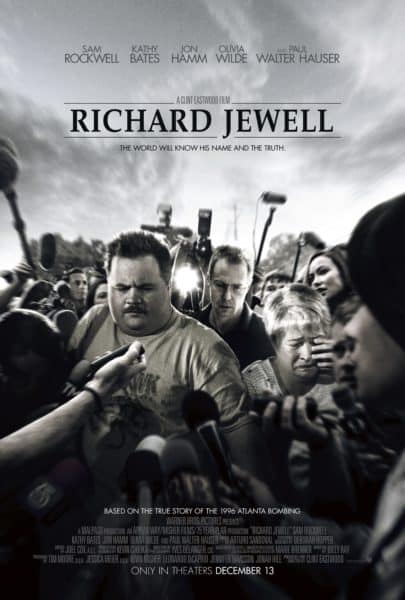

Richard Jewell, the Movie

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, December 23, 2019

Credit: WARNER BROS. / Album

Many white advocates loved Joker, identifying with the title character. Yet it’s not the year’s most important film. That film is Clint Eastwood’s Richard Jewell. Despite one major flaw, it’s a near-masterpiece. It’s also a warning. See it immediately.

The plot is straightforward, though Mr. Eastwood unfortunately invents a fictional character and a subplot for dramatic license.

Richard Jewell wants to be a police officer. The film portrays him warts and all. Star Paul Walter Hauser’s performance is perfect. When we first see Jewell, he’s a nosy janitor at a law firm. There, he meets Watson Bryant, who tells him not to become “an asshole” when Jewell achieves his dream and becomes a cop.

Jewell doesn’t listen. He abuses his power as a campus security guard, and lost his job as a sheriff’s deputy. He still keeps a picture of himself in uniform on his wall.

He lives with his mother, like the antihero from Joker. He hangs around “real” law enforcement, acting like someone who was never a soldier trying to impress combat veterans by using military lingo. He’s self-important, deluded, suspicious, and somewhat pathetic.

Yet it’s precisely these qualities that made him a hero. Richard Jewell becomes a security guard for the 1996 Olympics. A man calls 911 to tell authorities he’s planted a bomb. Jewell, who knows nothing about the call, finds a suspicious package. He insists the police follow protocol, even though they try to ignore him. When Jewell’s proven right and the bomb is discovered, he acts quickly to evacuate the area, saving many lives while risking his own.

Journalists initially make him a star. Though this is the moment Jewell’s been preparing for his whole life, he’s modest. He credits other officers and first responders with saving lives. He doesn’t boast. When he’s offered a book deal, he contacts Watson Bryant – who told him not to be “an asshole” – because he doesn’t know any other lawyers. Still, the FBI is suspicious.

This is all true. What Mr. Eastwood invents is Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Kathy Scruggs (played by Olivia Wilde) seducing FBI agent Tom Shaw (a composite character played by Jon Hamm) to find out the feds are investigating Jewell. She writes a story claiming Jewell is a potential suspect, sparking a media frenzy.

Olivia Wilde (Credit Image: © Robin Platzer / Avalon via ZUMA Press)

The seduction never happened because Shaw (obviously) never existed. The story and its aftermath were all too real. Reporters hound the former hero and traumatize his mother. Federal agents send in a spy, bug the house, take his belongings, and investigate everything about him. They almost trick him into signing a statement by claiming it’s for a “training video.” The shell-shocked Jewell keeps trying to cooperate with the FBI because he’s “law enforcement too.” Bryant, (who resembles the anti-government character Dale from King of the Hill) must repeatedly explain that federal agents aren’t Jewell’s friends; they’re but people trying to destroy him.

Eventually, Jewell learns the lesson. He passes a polygraph test arranged by his lawyer. Jewell’s mother and Bryant hold a press conference to demand President Bill Clinton clear Jewell’s name. During an FBI interrogation, Jewell bluntly asks if agents have any real evidence. When they admit they don’t, he and his lawyer leave. He eventually gets a letter from the government declaring he’s “not a target.” FBI agent Tom Shaw snarls that he still thinks Jewell is “guilty as hell.” Jewell is finally cleared completely when an entirely different person, Eric Rudolph, confesses. Yet to this day, many still think Jewell had something to do with committing the crime.

The film shows media and federal law enforcement are powerful political actors with their own agendas. They work together. Journalist Scruggs and Agent Shaw talk about and personify this co-dependence.

Law enforcement and media are not impartial arbiters of “truth,” and the film critiques a system that gives journalists so much power. Not surprisingly, many say this is lèse–majesté.

- “[A] MAGA screed calibrated to court favor with the red-hat wearing faithful by vilifying the president’s two favorite enemies: the FBI and the media.” — The Daily Beast

- “Richard Jewell will give plenty of oxygen to people who don’t want to save a free press, but destroy it.” — The Philadelphia Inquirer

- “It couldn’t be more obvious [why] Eastwood made the film in the first place: to demonize the same forces Donald Trump is now in the business of demonizing.” — Variety

There’s one major flaw in the film. Richard Jewell implies that Kathy Scruggs, who is dead and can no longer defend herself, traded sex for information. “No, Clint Eastwood, female journalists don’t trade sex for information,” said The Guardian in a representative article condemning the film.

However, just recently, journalist Ali Watkins was in a romantic relationship with James Wolfe, an aide on the Senate Intelligence Committee. She was reporting on the committee’s activities. She denies Mr. Wolfe was a source, but not even other journalists believe her. It’s not unrealistic to suggest journalists may trade sex for information.

Yet it’s irresponsible to attack a specific person without proof. Isn’t that what the film’s all about?

There’s no hard evidence Scruggs traded sex for a scoop. Actress Olivia Wilde claims she portrayed Scruggs like a feminist hero, but this is spin. In the film, Scruggs is scum. She cries somewhat redeeming tears during a press conference, but the film does to her what the media did on a larger scale to Jewell.

In real life, some say Scruggs’s remorse contributed to her drug-overdose death, and the film could have explored the psychological connection between Scruggs and Jewell. Both liked being considered an authority. Both were destroyed by the case. Both died young, Jewell at 44, Scruggs at 43. Though Scruggs was an ambitious, status-seeking journalist and Jewell a Southern good ol’ boy, they had a lot in common.

I think the film is unfair to Scruggs personally but too easy on journalists generally. There may be exceptions, but journalists must sensationalize, exaggerate, or even lie if they want to attract eyeballs. Eastwood lets journalism off the hook and smears a dead woman instead.

The film isn’t entirely one-sided on law enforcement, because it acknowledges the FBI wasn’t being pointlessly cruel. People do stage fake crimes. A police officer planted a bomb at the 1984 Olympics so he could be a hero, a case the film mentions. It’s the same motive behind “hate hoaxes.” What’s more, the FBI’s profile was basically correct. It was a white, male, right-wing extremist who committed the crime.

Yet Richard Jewell wasn’t a “profile,” but a person. FBI agents and reporters spit out the words “frustrated white male” with utter contempt when discussing Jewell. Circumstantial evidence about his background, his guns, and his associates made him look guilty. The media ripped Richard Jewell to shreds in the 1990s; it would have been much worse today. His weapons, his manner, and the simple fact he’s white would be enough to destroy him. He’d probably have a harder time finding a lawyer.

Paul Walter Hauser arrives at the AFI Fest 2019 – Premiere Of Warner Bros. Pictures’ Richard Jewell held at the TCL Chinese Theatre. (Credit Image: © Xavier Collin / Avalon via ZUMA Press)

At one point, Bryant’s Russian secretary says that in her country, when the government says someone is guilty, that’s proof he’s innocent. Still, Bryant doubts his client, until he independently confirms that there was no way Jewell could have planted the bomb and made the phone call. When Scruggs reaches the same conclusion on the same evidence, she’s horrified that she’s smeared an innocent man. She confronts Agent Shaw, who airily dismisses her by saying Jewell had an accomplice. Even though the film is hard on Scruggs, she comes off much better than the FBI.

No one says Richard Jewell is “racist” in the film. His lawyer asks whether he’s hung around with extremist groups, including the Ku Klux Klan, and Jewell says he “hates all that stuff.”

Yet the film contains important messages about race, class, and trust in civic institutions. Richard Jewell is the “profile” academia and media tell Americans to hate. He’s an unsophisticated, gun-owning, patriotic Southerner with a thick accent. When he’s under pressure, he eats junk food. Today, Jewell’s race would be considered even more damning than it was in 1996. I couldn’t help but notice the old Georgia state flag (based on the Confederate battle flag, the one which Stacey Abrams burned) in the background in several scenes. Scruggs and Shaw can barely conceal their loathing for the ordinary Americans dancing and clapping along to Kenny Rogers or the Macarena during the Olympic celebrations.

When reporters and book publishers initially swarm Jewell, he’s bewildered about what the “New York types” want from him. He speaks to reporters, never imagining they could turn on him. His mother admires Tom Brokaw for being handsome and (presumably) trustworthy. She’s horrified and confused when Mr. Brokaw calls her son a possible suspect. “Why’s Tom Brokaw saying that?” she wails. Richard Jewell personifies the “forgotten man” Donald Trump talked about during the 2016 campaign.

The Jewell case was a pivotal point for our culture. Today, most Republicans think media deliberately report “fake news.” The FBI’s shameful investigation into President Trump revealed what many suspected: federal law enforcement can be politicized and possibly corrupt. Many have lost faith in American institutions. Increased diversity has undermined social cohesion and trust.

Today, we know the government can collect everything we write, text, post, and possibly even say. Many Americans now understand that when a journalist calls you, he may want to hurt you. We all know what a “hit piece” is and what it’s designed to achieve.

We didn’t know all that in 1996. Before the internet, there was almost no alternative to television and newspapers. Why wouldn’t you trust journalists and the police? Thus, when Richard Jewell keeps trying to help or defend the very people who want him convicted, we understand. “I was raised to respect authority,” he says.

When Jewell finally realizes what the FBI is doing, there’s a black-and-white John Wayne movie playing on the television. It’s a powerful symbol of the older, better, more trusting America that’s lost forever. Near the film’s end, Jewell says that the FBI once represented the highest calling he could imagine. Now, he says, he’s not sure. He speaks for many Americans.

In the film’s climactic showdown with the FBI, Jewell says no one will speak up as he did because no one wants to become “another Richard Jewell:” a media/government target. He’s right. No one spoke up about suspicious Middle Eastern men getting flight training before September 11, 2001. No one denounced Nidal Hasan before the Fort Hood shooting, even though Mr. Hasan repeatedly made extremist, anti-American statements. No one stopped bringing Saudi pilots for training to American military bases, even after the Pensacola shooting. Why? They’d be called racist. “We’d rather die than be thought of ‘Islamophobic,’ said Kate Smyth, quoted in a Mark Steyn column calling the West “Too Stupid To Survive.”

Yet we’re not “too stupid.” We’re afraid. If you “see something [and] say something,” like the Department of Homeland Security suggests, get ready for a media swarm. Look what happened to Irving, Texas when student Ahmed “Clock Boy” Mohamed brought a suspicious device to school.

In some ways, Richard Jewell portrays a vanished world, in which there’s no “woke” culture, no “white privilege,” no internet. Today, we’re more cynical. Race is not just a background issue, but the driving force of American politics. The Macarena has, mercifully, vanished.

Yet this film is vital. With unsparing simplicity and brutality, it shows what media and law enforcement can do to the well-meaning and naïve. It shows that most people will believe initial reports, and that the truth, if it ever emerges, will just be background noise. Unaccountable, unelected federal authorities and malevolent reporters often govern us, not the Constitution.

See Richard Jewell and absorb its lessons. Don’t talk to the police. Don’t trust a journalist. Most of all, don’t assume your supposed guardians want to help you. You’re just another “frustrated” white person. You’re prey.