Diversity Destroys Trust

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, September 2007

Not a recipe for success.

Robert Putnam of Harvard became an academic celebrity in 2000 with his book, Bowling Alone, which argued that society is in dire straits because so many community attachments are breaking down. Americans are increasingly mobile and isolated, with few group affiliations. Prof. Putnam wants to bring back what he calls “social networks,” because he says they make people happy, contribute to democracy, help rear children, and make the economy run better.

He later analyzed census and survey data to find out what role racial diversity plays in all this — whether it deepens attachment to community or further atomizes people. To his dismay, he found that racial and ethnic diversity destroys trust in neighbors and institutions.

Prof. Putnam did not like these findings, and was in no hurry to publish them, but a reporter for the Financial Times may have forced his hand. In an article that appeared on October 9, 2006, John Lloyd quoted Prof. Putnam as saying that he was studying ways to compensate for the bad effects of diversity and that it “would have been irresponsible to publish without that.”

Prof. Putnam deeply regrets his words. No one likes to admit so openly that he is going to bathe, barber and perfume the findings before he lets the public see them. In an interview several weeks later with the Harvard Crimson, Prof. Putnam implied that Mr. Lloyd quoted him dishonestly, and called it “almost criminal” that the Financial Times had not emphasized his belief that in the mid- to long-run, people learn to like diversity and that society is stronger for it. His unhappiness was compounded by hundreds of e-mail messages from what he called “racists and anti-immigration activists” congratulating him on discovering the obvious.

Professor Robert Putnam

Professor Putnam has now published his study in the latest issue of Scandinavian Political Studies (Vol. 30, No. 2, 2007, pp. 137-174.) He does his best to give the article a happy ending, but his findings are hard to sugarcoat.

Whom Do You Trust?

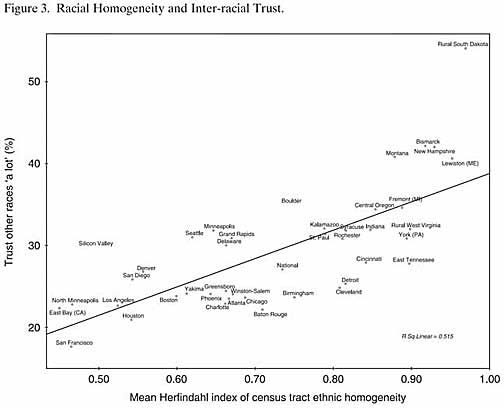

This study is a survey of people living in 41 different American communities that run from racially homogeneous rural South Dakota to San Francisco, which is one of the most racially mixed places on earth. The clearest finding was that the more diverse the area, the less people trusted each other. The graph on page three represents this by showing the 41 areas on a plot, with trust of other races on the vertical axis and an index of homogeneity on the horizontal axis.

(Prof. Putnam measured homogeneity with what is called a Herfindahl index, which is the likelihood that two randomly selected people in a given area — in this case a census tract — will be of the same race. A value of 1.00 means there is a 100 percent chance they will be the same, and a value of 0.50 means only a 50 percent chance.)

The study divided people into four groups — white, black, Hispanic, Asian — and asked whether they trusted the other groups. The percentage that said they trusted the other three groups “a lot” is on the vertical axis. Rural South Dakota and Lewiston, Maine, over to the right, were about as pure white as it was possible to be (this was in 2000, before Somalis converged on Lewiston because of its generous welfare) and had some of the highest levels of trust in “other races.” As diversity increases towards the left, trust in other races decreases.

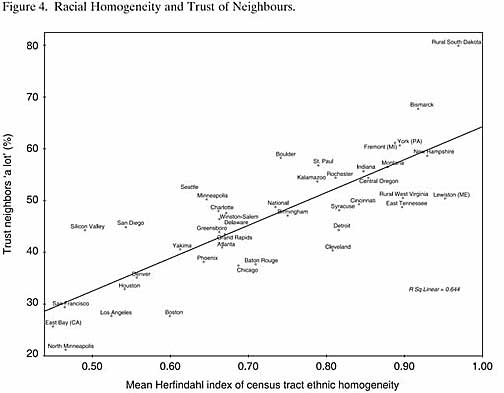

The second graph, on page four, is a similar plot, except that the question was whether respondents trusted their neighbors “a lot.” Prof. Putnam recognizes that people usually have neighbors like themselves, so this question can be seen as an indication of trust not only in neighbors but in people like oneself. As the graph shows, people in virtually all areas are more likely to say they trust their neighbors “a lot” than to say they trust people of other races “a lot,” but again, the more diversity, the less trust.

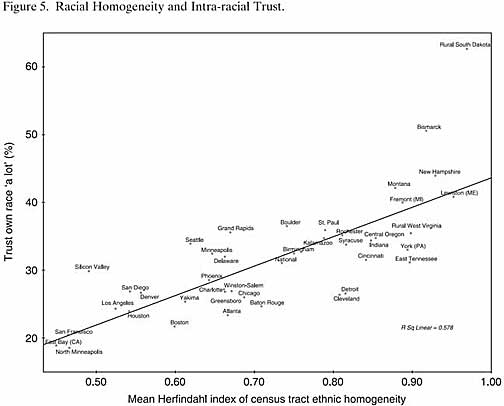

The third graph, on page five, shows the results of asking whether people trust members of their own race “a lot.” Prof. Putnam points out that if diversity makes people distrust people of other races, it might be expected to increase their trust in people of their own race — and here is the surprise: Diversity reduces trust in everyone, even in people of one’s own race. This is what leads to Prof. Putnam’s widely quoted conclusion that diversity makes people behave like turtles — they pull into their shells. On the basis of other survey data, he lists other unhappy consequences for people who must live with diversity:

- Lower confidence in local government, local leaders and the local news media.

- Lower political efficacy — that is, confidence in their own influence.

- Lower frequency of registering to vote, but more interest and knowledge about politics and more participation in protest marches and social reform groups.

- Less expectation that others will cooperate to solve dilemmas of collective action (e.g., voluntary conservation to ease a water or energy shortage).

- Less likelihood of working on a community project.

- Lower likelihood of giving to charity or volunteering.

- Fewer close friends and confidants.

- Less happiness and lower perceived quality of life.

- More time spent watching television and more agreement that “television is my most important form of entertainment.”

This is a convincing set of reasons to oppose the sort of diversity we are always told to celebrate. Indeed, it confirms what immigration activists and race realists have been saying for decades. These findings alone, and the publicity they have received, are worthy of, well, celebration.

Prof. Putnam admits he did not like the results, and carefully sifted and diced the data to find something other than diversity — poverty, age, crime, population density, education, commuting time, home ownership rates, anything — that seemed to be destroying trust. He did learn some useful things: Young people are less trusting than old people, blacks and Hispanics are less trusting than whites and Asians, people who live in high crime areas are not very trusting, nor are the poor and uneducated. Still, the master variable was diversity. “Diversity per se has a major effect,” he writes.

However, let us return to the three tables, which hint at interesting information Prof. Putnam did not include in his report. The most homogeneous neighborhoods he investigated are overwhelmingly white. There are census tracts that are overwhelmingly Hispanic or black — and therefore homogeneous — but he did not report results for them. This research therefore should more properly be thought of as a study of the effects of diversity on whites. It would be interesting to know its effect on blacks or Hispanics.

If homogeneity is an advantage, blacks who live in the ghetto should benefit from it just as whites do. Compared to blacks who live in mixed neighborhoods, do they trust white people more, do a lot of volunteer work, spend less time watching television, and have more confidence in local government? Probably not.

It may very well be that homogeneity does not affect non-whites the same way it affects whites. It has been known for years that whites in racial isolation have a higher opinion of blacks than do whites who live close to them. During Jesse Jackson’s campaigns for US president in 1984 and 1988, his percentage of the white vote was highest in areas with the fewest blacks. This is probably because whites whose knowledge of blacks comes only from the media have a better opinion of them than whites who have direct contact with them. This alone could explain why people in homogeneous white areas think highly of people of other races.

Would the same be true for blacks and Hispanics? Perhaps not. The media routinely blame whites for racial tension in America, so blacks and Hispanics who have the least contact with them may have the most reason to distrust them. On the other hand, heavily black and Hispanic neighborhoods are not usually nice places. People who live in them may think white people are not so bad after all.

There is another problem with these graphs of trust. For the overwhelmingly white areas, we know that the respondents to the surveys are overwhelmingly white — the results reflect white attitudes. For the other areas, because Prof. Putnam lumps respondents of all races together, we do not know if there are racial differences in attitudes. He says blacks and Hispanics are generally less trusting than whites. This means white expressions of lack of trust probably do not drop as steeply with diversity as these graphs suggest because they show overall responses rather than responses by race. It may be that in the diverse locations, the white response — Prof. Putnam says it is more trusting — is being overwhelmed by untrusting blacks and Hispanics.

There are hints that this might be so. North Minneapolis shows up on these graphs as one of the most diverse places in America, but it is known as the blackest, poorest, most crime-ridden place in Minnesota. This is probably the closest thing the study offers to a genuinely black response, but it is blurred because the ethnic homogeneity index tells us there are many non-black people who live there, too — probably Hispanics.

However, we find some intriguing results Prof. Putnam ignores. The people of virtually every other location trust their neighbors considerably more than they trust people of other races. Not the people of North Minneapolis. A comparison of the first two graphs shows that slightly fewer trust their neighbors “a lot” than trust people of other races. And, in fact, a comparison with the third chart shows they trust people of their own race least of all! Surely, these interesting data deserve disaggregation. Do people of all races in North Minneapolis trust their own race least of all? Only blacks? Only Hispanics? Blacks who live in high-crime ghettos may have good reason to distrust blacks more than whites.

Boston gives queer results, too. People trust their neighbors only slightly more than they trust people of other races and, again, appear to trust people of their own race least of all. This sort of thing cries out for explanation but Prof. Putnam offers none.

Something else that stands out on the first chart is that every single one of the Southern study areas — Charlotte, Atlanta, Baton Rouge, Greensboro, Winston-Salem, Birmingham, East Tennessee — is below the trend line. This means that without regard to diversity or homogeneity, people living in the South are less likely than people of other regions to trust people of other races. This is probably because the most common racial division in the South is still black/white, and suggests that this is the color line that still causes the most distrust.

There is sure to be other interesting information in this study that did not make it into print. Whom do blacks distrust more: whites or Hispanics? Whom do Asians distrust? Does increased diversity increase distrust of all other races or just some? The data probably could have been given a more fine-grained analysis, but Prof. Putnam does not provide it.

A Dizzying Spin

Now that Prof. Putnam has found that diversity makes people watch more TV, distrust local government, stop voting, suspect the local media, give less to charity, and makes them just plain unhappy, how does he defend it? He spins his story two different ways, first by arguing that people eventually learn to like it. His proof? That WASP-run, WASP-founded America managed to absorb the European ethnics who swarmed in at the turn of the 20th century. This lesson in happy history ignores blacks and Indians, who have been here a lot longer than the white ethnics but are still not absorbed. Prof. Putnam does mention in passing “the possibly more visible distinctiveness of contemporary migrants,” but doesn’t seem to think this will make any difference.

He also ignores the fact that European ethnics were absorbed because they learned English and became largely indistinguishable from WASPS by such measures as income, education, crime rates, etc. It was a one-way street: They became Americans. People didn’t learn to like diversity; the newcomers became more like the old-timers, and the diversity went away.

Prof. Putnam’s second assertion is that diversity is inherently good. Once we have overcome our dislike for it, as we surely will, Prof. Putnam’s big argument in its favor is that it stimulates creativity. He tells us immigrants have been four times more likely than the American-born to win the following honors: Nobel Prizes, Academy Awards for film directing, Kennedy Center awards in the performing arts, and membership in the National Academy of Science.

Assuming this is true, it is one of the silliest arguments for “diversity” anyone ever tried. We keep hearing “diversity” is good for us. If Prof. Putnam were somehow able to show that immigration so stimulated native-born Americans that they won Nobel Prizes at four times the rate they would have without immigration he would be on to something. His figures show only that we have had some smart immigrants. Did they become smarter or more creative because they met WASPS? Very unlikely — though they probably had better opportunities. Virtually all these paragons were certainly white, many were probably Jews, and most would undoubtedly have had distinguished records wherever they lived. The idea that “diversity” had something to do with what they achieved is nonsense.

There is another way to show the absurdity of Prof. Putnam’s argument. Let us imagine the United States had never had mass immigration, never pretended diversity was a strength, but had let in only white people with IQs over 140. Immigrants might then be 100 or even 1,000 times more likely than natives to win Nobel prizes. Would Prof. Putnam call that an even stronger argument for “diversity?”

Finally, Prof. Putnam implies that Mexicans will be joining the National Academy of Sciences at four times the white rate. Not likely. They are in prison at four times the white rate.

The whistling-past-the-graveyard tone to this study is even more noticeable because Prof. Putnam cites many other studies that confirm his basic (and obvious) finding: Diversity decreases trust. He reports that people in “diverse” workgroups — not only of race but also age and professional background — are less loyal to the group, more likely to resign, and generally less satisfied than people who work with people like themselves. Prof. Putnam even cites a study that found carpooling is less common in mixed neighborhoods. Carpooling means counting on your neighbors to get you to work, and people tend not to trust neighbors who don’t look like them.

Prof. Putnam cites half a dozen studies from places as varied as Australia, Sweden, and Canada showing that ethnic diversity lowers levels of trust and, in some cases, lowers investment in public goods. It is well known, for example, that welfare systems are usually more generous in homogeneous countries because people are more willing to pay taxes to support beneficiaries who look like they might be cousins.

It is the same everywhere. In Peru, there are what are called micro-credit cooperatives that make small loans to members. Apparently, when there is diversity among co-op members, default rates are higher. Likewise, in Kenyan school districts, fundraising is easier in more tribally and ethnically homogenous areas.

Prof. Putnam even offers an interesting historical example. In the Union Army during the Civil War, casualty rates were high and the chances of being caught for desertion were low. Aside from patriotism, it was loyalty to their messmates that kept soldiers in the fight. Not surprisingly, desertion rates were higher in units with the greatest diversity, not just of ethnicity but even of age, hometown, occupation, etc.

The preference for one’s own kind is deeply rooted in human — even animal — nature. There is nothing surprising about Prof. Putnam’s findings or the other research he cites. What is surprising is his desperate faith in the eventual benefits of something that clearly does not work anywhere.

Prof. Putnam concludes his study with the usual bromides: “[W]e need more opportunities for meaningful interaction across ethnic lines.” “[L]ocally based programs to reach out to new immigrant communities are a powerful tool for mutual learning.” Note the words “interaction” and “mutual learning.” The purpose of all this is not to turn immigrants into Americans the way we used to: “[M]y hunch is that at the end we shall see that the challenge is best met not by making ‘them’ like ‘us,’ but rather by creating a new, more capacious sense of ‘we,’ . . .” All of us, in other words, should become a little bit Haitian, a little bit Chinese, and quite substantially black and Mexican. We should probably get into practice right now for becoming a little bit Iraqi, in preparation for the “allies” who will surely follow our troops home.

In his final sentence Prof. Putnam tells us that even the motto on the Great Seal of the United States, e pluribus unum (out of many, one), is a celebration of diversity. Either Harvard is not what it used to be or Prof Putnam is trying to pull a fast one on the readers of Scandinavian Political Studies. The motto, of course, refers to the 13 colonies uniting as one nation, not to ethnic mixing.