The Hour of Decision

Jon Harrison Sims, American Renaissance, January 24, 2014

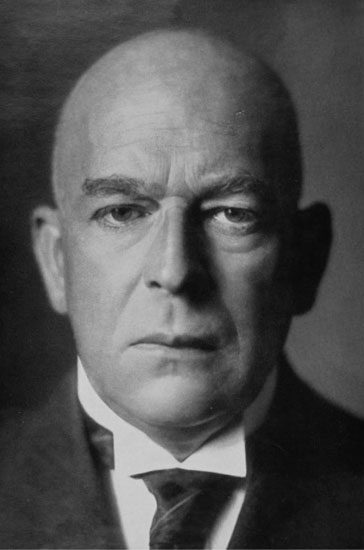

Oswald Spengler, The Hour of Decision: Germany and World-Historical Evolution, University Press of the Pacific; 230 pp., $24.75.

If The Decline of the West is one of those great books everyone knows about but few have read, The Hour of Decision is a great book that few even know about. That is a shame, because this is a prophetic book that has much to teach us.

Written in 1933, 15 years after Spengler’s masterpiece of cultural and historical reasoning, The Hour of Decision is a warning to the white race of two perils, one from below and one from without: class war and race war. By the first, he meant a working class uprising led by professional revolutionaries; by the second, colonial rebellion against white rule. The first threat has passed, but the second has been realized: White minority rule has been overthrown everywhere; South Africa was the last holdout.

A new danger has arisen, one that Spengler did not foresee: the mass migration of non-whites into the West. While Spengler did not anticipate this — how could he? — he saw the cultural, intellectual, and political pathologies that prepared the way for it, and his dissection of these forces is of great value.

Curiously, Spengler claimed to have a non-biological view of race, calling racial purity a “grotesque word” in view of what he calls centuries of race mixing. “What is needed is not a pure race,” he wrote, “but a strong one.” This assertion is confined to one short paragraph, is hardly an argument, and is essentially contradicted by the whole tenor of the rest of his book.

I believe that this scientifically unsound and evidentially weak statement has been misunderstood. Spengler would never have countenanced miscegenation or mass immigration and may well have been using the word “race” in the sense of the “the British race” or “German race,” as was common in his time.

Spengler’s views make sense in the light of his pan-European ideals. He believed it was imperative that Europeans stop fighting each other and unite in a continental confederation for defense of both the European homeland and overseas possessions. Because Europeans were, even then, a small minority of the world’s population, it was essential that they remain united. Thus, Spengler’s dismissal of racial purity was probably an attempt to blunt excessive expressions of Germanic and Scandinavian racial superiority. The comradeship of Slavs or Iberians should not be rejected, since they are fellow whites. That said, Spengler did believe in Nordic superiority. He wrote that “the Celtic-Germanic ‘race’ is the strongest willed that the world has ever seen,” and he stressed the importance of cultivating “the relic of healthy race-instinct, the trace of Nordic heroism left in these nations.”

“Hatred of the white race”

For Spengler there were no victors in the world war of 1914 to 1918. All white nations had lost because they had squandered their best men and valuable capital for no good purpose. He called the result “a defeat of the white races;” the division and carnage emboldened the colored peoples to think they could free themselves from European rule. However, Spengler warned that the colonial peoples were motivated by more than the desire for self-determination. They were driven by “hatred of the white race and an unconditional urge to destroy it.” He believed this hatred was driven by envy. “Envy is the crooked glance from below at something higher, which remains uncomprehended and unattainable, and must therefore be pulled off its perch, sullied, and destroyed.”

Such envy could be class based: the hatred of the upper bourgeoisie for the landed aristocracy and of the proletariat for the middle class. It could also be race based: the envy of non-whites for whites, because non-whites can achieve neither the aesthetic perfection of whites nor their refined way of life. Neither education nor money changes racial characteristics. The closest a person of color can come to “becoming white” is to marry a white woman or a white man, and have lighter-skinned children.

Spengler’s view is fully confirmed by ever-increasing anti-white rhetoric and politics. Forty years of welfare, affirmative action, racial quotas, and liberal immigration have not appeased but increased the antipathy of the beneficiaries toward the white majority. Clearly, the brown and black races will be satisfied with nothing less than the expropriation of all white lands. Spengler’s opening passage therefore has even greater resonance now than when he wrote it:

Is there today a man among the White races who has eyes to see what is going on around him on the face of the globe? To see the immensity of the danger which looms over this mass of peoples?

Another danger was the prospect of “a second world war” coming after the “first world war” of 1914-1918. These were Spengler’s exact words, remarkably prescient for 1933. He did not name the belligerents, but it is clear he thought National Socialist Germany and Communist Russia would be on opposite sides. The Russians might be white, but their embrace of internationalist socialism meant that they had become culturally and politically part of Asia. Even so, Spengler warned Germans of the folly of invasion:

The population of the mightiest of the earth’s inland areas is unassailable from outside. Distance is a force, politically and militarily, which has not yet been conquered. Napoleon came to know this. What good does it do an enemy to occupy areas no matter how immense? To make even the attempt impossible the Bolsheviks have transferred the centre of gravity of their system farther and farther eastward. The great industrial areas which are important to power politics have one and all been built up east of Moscow, for the greater part east of the Urals. The whole area west of Moscow — White Russia, the Ukraine, once from Riga to Odessa the most vital portion of the Tsar’s empire — forms today a fantastic glacis against ‘Europe.’ It could be sacrificed without a crash of the whole system. But by the same token any idea of an offensive from the West has become senseless. It would be thrust into empty space.

Spengler believed Peter the Great had westernized Russia and brought it into the white world, making it white by both race and culture. The Bolsheviks had reversed that achievement and Orientalized Russia. One could argue that President Putin, an Eastern Orthodox Christian and a white patriot, has brought Russia back into the European world, while the United States, now officially multi-racial, has ceased to be part of the West. This is how Spengler saw the United States in 1933, despite the immigration restrictions of 1924:

All we know is that so far there is neither a real nation nor a real state . . . [but only] a boundless field and a population of trappers, drifting from town to town in the dollar hunt, unscrupulous and dissolute; for the law is only for those who are not cunning or powerful enough to ignore it.

Spengler saw America’s recent immigrants as “an alien, foreign-thinking, and very prolific proletariat.” America’s war-time unity and victory over Japan proved that the country was not as far gone as Spengler believed. However, his characterization applies all too well to post-Cold War America. Second- and third-generation immigrants have shown resentment rather than gratitude toward their adopted country.

Spengler’s critique of America as rootless, uncultured, and devoted to pleasure and money making was part of his critique of liberal economics as one of the prime causes of Western decline. In his view, economics should always be subordinated to politics, by which he meant, made to serve the welfare of the people, not the profits of the plutocracy. Economics should be about ordering the economic life of the nation so as to augment its inner strength and organic unity. Instead, it had become a “method by which with the least exertion the most money and pleasure can be secured.”

By so doing, economics had fostered class divisions and driven the working class into the arms of ruthless revolutionaries. Spengler wrote that “the manual worker is merely a means to the private ends of professional revolutionaries. He is to fight for the satisfaction of their hatred for the conservative forces.” He added that “their ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ ” was merely “their own dictatorship with the help of the proletariat.” Similarly, he denounced political liberalism as “the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie.”

Spengler believed parliamentary politics across the Western world had become dominated by selfish interests competing for the favors of a bureaucratic state, with capitalist and socialist parties as two sides of the same base coin. His proposed an alternative that he called Prussianism, which stood for “the aristocratic ordering of life.” There must be hierarchy, but it must not be based on money. “The Prussian idea,” he wrote, “is opposed to finance-Liberalism as well as to Labour-Socialism.” It was “opposed to any weakening of the State and to the misuse of it for economic interests.” It stood for “possessions,” meaning land, well-built houses, farms, and real businesses. It also stood for “inheritance, fecundity, and family, which three belong together; [and] for distinctions of rank and social gradation.” Some have seen the British aristocracy in this light. It governed with inherited authority and a sense of national ownership that led to policies in the common interest.

Spengler believed Germany was the youngest and healthiest of the European nations, relatively uncorrupted by money and individual selfishness, and still possessed of the elements of “Prussianism.” Germany stood guard at the borders of Asia, and was thus “the key country” of the West, the potential “educator of the white world, and perhaps its savior.”

It is therefore a surprise to learn that after the National Socialists came to power they quietly proscribed Spengler and suppressed his books. The German press was directed not to write about Spengler and his books were taken off the shelves. The Decline of the West would not be available in Germany again until 1950. Spengler’s projected second volume of The Hour of Decision never appeared, either because he did not finish it or because the Gestapo confiscated the manuscript after he died in 1936. The regime suppressed Spengler because of his alleged rejection of the biological basis for race, his mild opposition to anti-Semitism, and for negative comments he made about Hitler. Spengler was not a Nazi.

An important lesson Spengler has for whites living in an increasingly decadent West is the imperative of having large families. The prevailing custom of having one, two, or no children is as great a danger to the white world as non-white immigration. Small families may, in theory, be good for the environment, but unborn white children are replaced by non-white children of immigrants.

As Spengler realized long before the post-1960s decline in birth rates, “the decay of the white family, the inevitable outcome of megapolitan existence, is spreading and is devouring the race of nations,” adding, “People live for themselves alone and not for future generations.” He believed that a vigorous people does not believe a higher standard of living is more important than having children: “A woman of race does not desire to be a companion or a lover, but a mother.” A man of race “wants stout sons who will perpetuate his name and his deeds beyond his death . . . and enhance them. That is the Nordic ideal of immortality.” The West’s colonization of large parts of the non-European world was possible only because of large families, and this is how we must defend our lands and ensure our survival.