How Well Do Hispanics Assimilate?

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, September 29, 2012

There are more than 50 million Hispanics in the United States and they make up about 16.5 percent of the population. The Census Bureau predicts that by 2050 there will be 133 million Hispanics, who will be 30 percent of the population. How well do Hispanics assimilate?

Identity

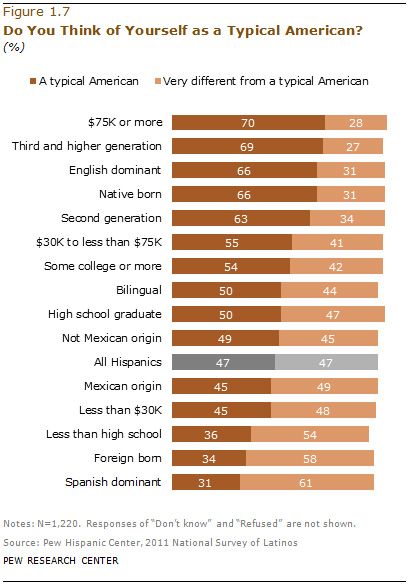

One way to measure this is to ask Hispanics themselves. Half of them say they are “typical Americans,” while the rest say they are “very different from typical Americans.” The graph below, taken from a 2011 Pew Hispanic Center study, shows which groups are most likely to say they are “typical.” Being born in the United States and speaking English makes Hispanics more likely to say they are “typical,” but over one quarter of “third and higher generation” Hispanics still say they are “very different” from typical Americans. (Most of the graphs used in this article list their source. To read the original report, please see the sources and links at the end of this article. Clicking on some graphs will lead to the source.)

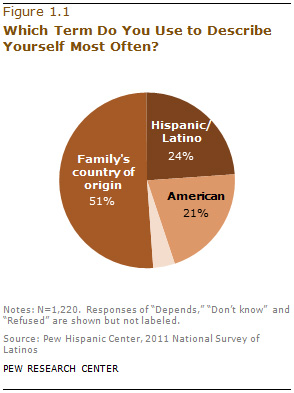

How Hispanics think of themselves is an indicator of assimilation. As the table below shows, more than half of Hispanics identify with their parents’ nationality — Mexican or Guatemalan, for example — and only 21 percent call themselves “Americans.”

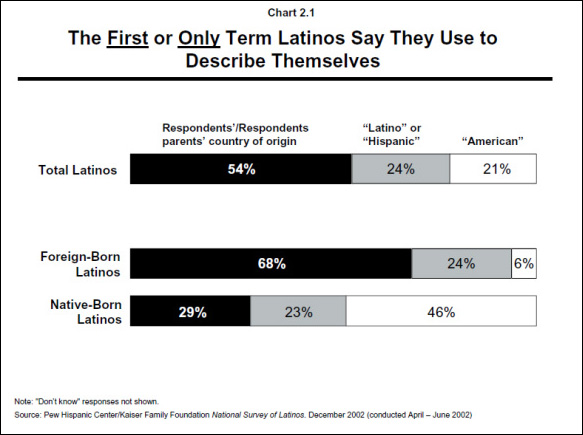

A more fine-grained but older study of what Hispanics call themselves found a large difference between foreign-born and American-born Hispanics, with 46 percent of American-born Hispanics calling themselves “Americans.”

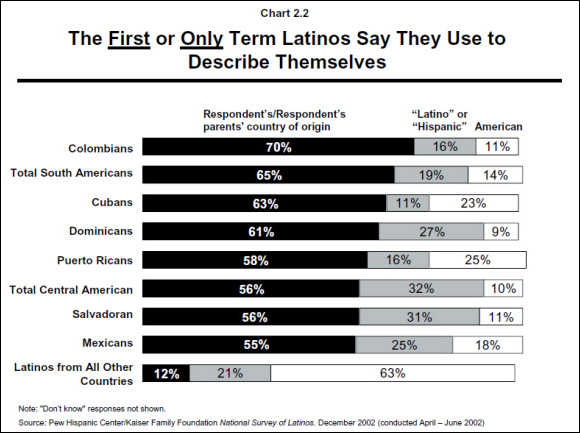

The same study found some variation by country of origin in how Hispanics think of themselves, with Puerto Ricans and Cubans most likely to call themselves “Americans.” The majority of Cubans immigrated shortly after the Castro revolution in 1959, so they have been here a long time. Puerto Rico is a commonwealth of the United States, and Puerto Ricans travel on United States passports. Still, only about a quarter of both groups call themselves “Americans.”

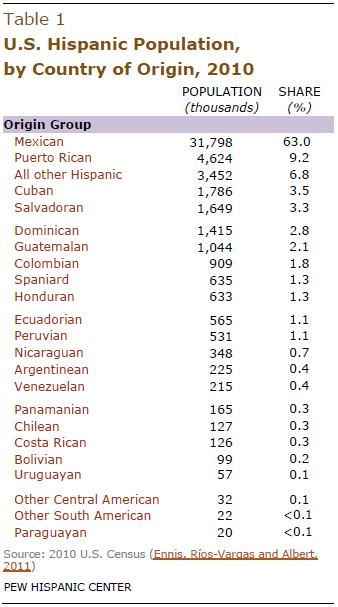

Of course, the Hispanic group that matters most is Mexicans, who account for 63 percent of US Hispanics. Puerto Ricans are 9.2 percent of all Hispanics and Cubans are only 3.5 percent.

The Census Bureau considers Hispanics a non-racial, linguistic/cultural group whose members can be of any race. However, most Hispanics don’t like the racial categories — white, black, Asian — available to them. The graph below shows that 56 percent think their race should be “Hispanic.” The American government, most notably when it collects crime statistics, considers Hispanics to be white, but only 20 percent of Hispanics consider themselves white.

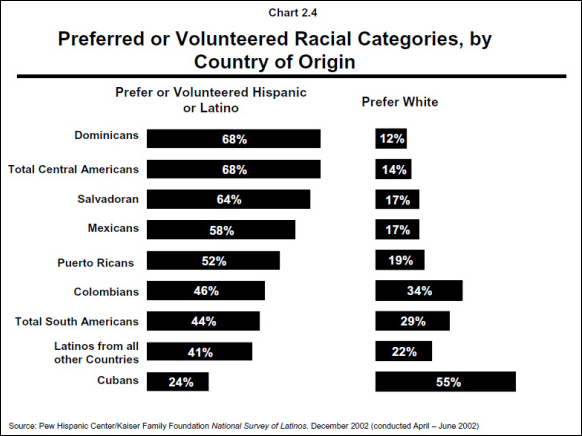

As the next table shows, Hispanics from different countries vary in how many consider themselves white. More than half of Cubans but only 12 percent of Dominicans say they are white. Seventeen percent of Mexicans, the largest group, say they are white.

Unlike the European ethnics who came to the United States from Italy or Hungary, for example, Hispanics do not want to give up their language. Fully 95 percent say it is very important (75 percent) or somewhat important (20 percent) for future generations of Hispanics to speak Spanish. This is not an expression of a desire to be “typical Americans.”

Hispanics do not immigrate because they want to be like Americans or because they seek “political freedom” or “participatory democracy.” Fifty-five percent say they came for economic reasons and 24 percent to join relatives. No fewer than 87 percent of Hispanics say they can get ahead better in the United States than in their home countries.

Discrimination

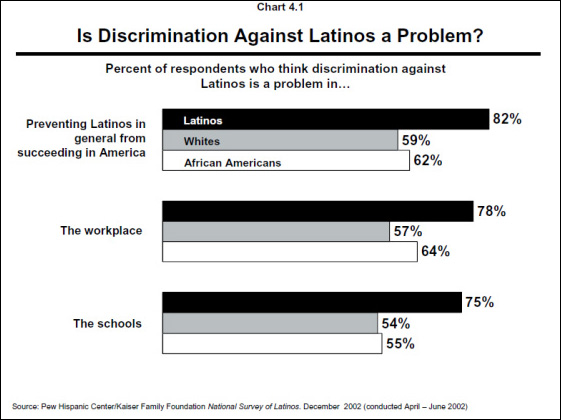

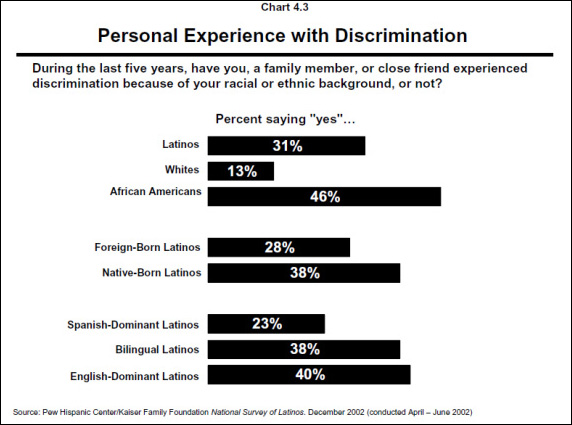

Hispanics are doing better here than back home despite what they see as widespread anti-Hispanic bias. As the graph below indicates, fully 82 percent think they have to fight discrimination to get ahead. Substantial numbers of blacks and whites appear to agree.

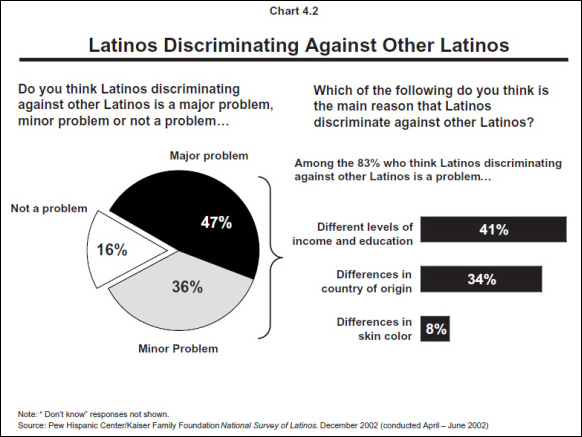

Interestingly, as the next graph shows, no fewer than 83 percent of Hispanics say that Hispanics discriminate against each other, but they would presumably say that discrimination from whites is a greater problem.

The longer Hispanics are here and the more “American” they become, the more likely they are to say they face discrimination. Perhaps this is not surprising. Detecting discrimination is a finely honed skill in the United States, and those who claim to have suffered from it are rewarded, whereas back home in Mexico or El Salvador they would be ignored. Thus, we see from the graph below that native-born Hispanics are more aware of discrimination than the foreign-born, as are those who speak better English than Spanish.

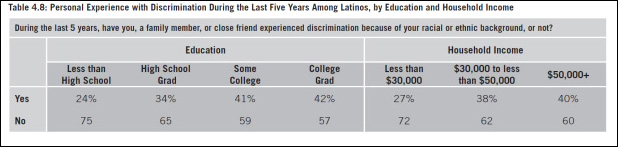

The next table shows that the more education they have had and the more money they make, the more likely Hispanics are to say they have suffered from or know about cases of discrimination. Recognizing discrimination seems to be part of becoming increasingly “American.”

Likewise, younger Hispanics are better at detecting discrimination than their elders. Fifty-two percent of 18- to 29-year-olds say they have been treated disrespectfully because they are Hispanic but only 28 percent of those 55 and older make that claim.

Politics

It is well known that Hispanics are politically more liberal than whites, but the generational dynamic is an interesting one. Because many Hispanics come from countries where citizens are said to fear and dislike their government, it would not be surprising if Hispanic immigrants brought a mistrust of government with them. This is not the case. As the graph below shows, no fewer than 81 percent of first-generation Hispanics want bigger government and more services, with that percentage decreasing with every generation. The “more services” part of it is no doubt an important reason for immigrating.

As Hispanics make more money and pay more taxes, they become more like other Americans in their desire for smaller government. However, even third-generation Hispanics are 17 percent more likely than what this table calls the “general population” to want big government and more handouts. The “general population” includes blacks, who also want government services, so the distance between Hispanics and whites is even greater.

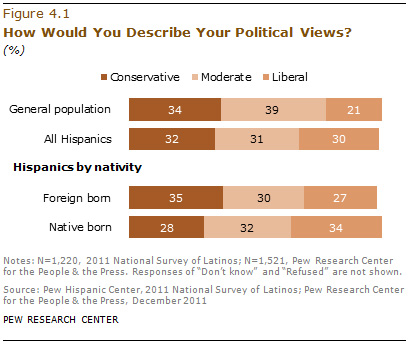

Many Hispanics describe themselves as “liberal.”

In this case, US-born Hispanics are more “liberal” than immigrants. This probably reflects the fact that even though when they start paying taxes they become less enthusiastic about paying for handouts, their views on other things change. A 2002 study found that most immigrant Hispanics oppose homosexuality, divorce, and abortion, and believe that the husband should have the final say in the family. US-born Hispanics absorb more liberal positions on these questions.

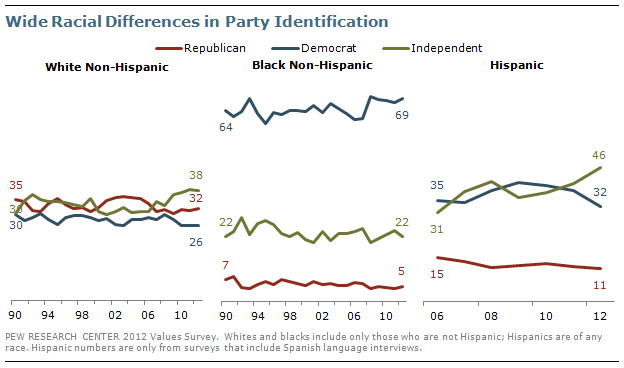

The graph below shows the political affiliations of people of different races. Over the last 12 years, the percentage of whites who call themselves Republicans has dropped from 35 to 32 percent, while the percentage who self-identify as Democrats has fallen from 30 to 26 percent. There are now more white “independents” than anything else. Republicans are in a hopeless position with blacks, and are not much better off with Hispanics, only 11 percent of whom identify as Republicans.

One indication of the politics of Hispanics is the people they consider to be their leaders. Aside from celebrities, the prominent Hispanics most familiar to Hispanics are Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor (67 percent of Hispanics have heard of her), Spanish-language television anchorman Jorge Ramos (59 percent), and Los Angeles mayor and former MEChA member Antonio Villaraigosa (44 percent). Among the 67 percent who have heard of Miss Sotomayor, 68 percent consider her a leader, which means that 46 percent (67 percent x 68 percent) of Hispanics consider her a leader of their people. Perhaps her view that “wise Latinas” make better decisions than white men adds to her appeal. A Supreme Court justice is supposed to interpret the Constitution, not be a leader of a racial or ethnic group.

Television personality Jorge Ramos, an unapologetic Hispanic chauvinist, is the number-two leader of American Hispanics. In a 2004 book about the United States he wrote, “We are everywhere, and there is no occupation or activity in this country that escapes our influence. This century is ours.”

General Attitudes

For a group that has taken the trouble to immigrate — sometimes at considerable risk — Hispanics are strangely fatalistic. The table below shows that more than half of foreign-born Hispanics think there is no point in planning for the future because they have no control over it. As they spend more time in the United States, they become less fatalistic, but do not catch up with whites.

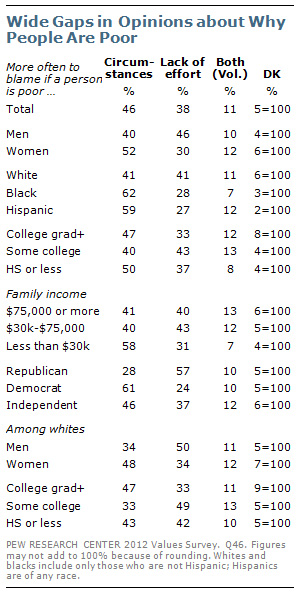

Hispanics show the same fatalism about the reasons people are poor. As the table below shows, whites are split as to whether the problem is lack of effort or bad circumstances, but twice as many Hispanics blame circumstances rather than lack of effort (“DK” means “don’t know”). There are other interesting splits, with white women much more likely than white men to blame circumstances, and there is an even greater split between Democrats and Republicans.

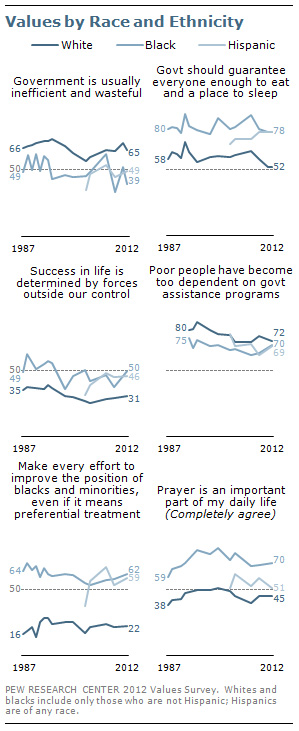

The next set of graphs shows that in some important respects Hispanics think like blacks. They have faith in government, and believe it should guarantee food and shelter for everyone. Like blacks, they are also solidly in favor of racial preferences in favor of themselves (at 59 percent, they are just behind blacks at 62 percent), whereas only 22 percent of whites support preferences. It would be interesting to know why they believe immigrants should receive preferences over natives.

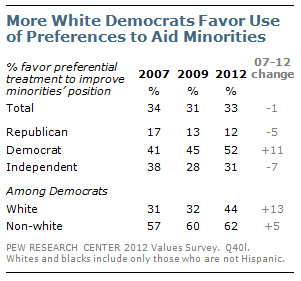

The next table shows how attitudes towards racial preferences have changed in recent years. Democrats have shifted towards them with Republicans moving against them. Forty-four percent of white Democrats now favor racial preferences that discriminate against their own children.

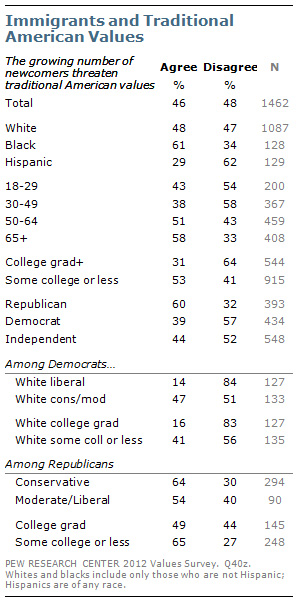

The next table shows that Hispanics overwhelmingly disagree with the idea that immigrants threaten traditional American values while conservative Republicans are most worried about the threat to values. The more Americans are exposed to higher education, the more favorably they view immigration.

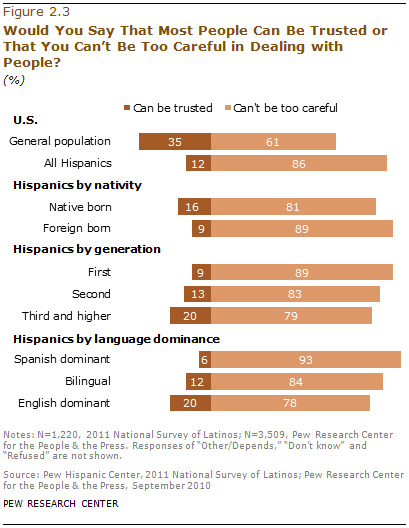

Hispanics tend to come from countries where people do not trust each other. Such countries are said to lack “social capital,” and anything that requires cooperation is more difficult than in countries where there is more trust. As the graphs below show, the more time they spend in the United States, the more they begin to trust people in general, but even after the third generation, 15 percent fewer Hispanics than other Americans (which includes blacks) say that most people can be trusted. Because there is so much Hispanic immigration, foreign-born Hispanic adults outnumber the US-born: In 2008, the figures were 53 percent and 47 percent.

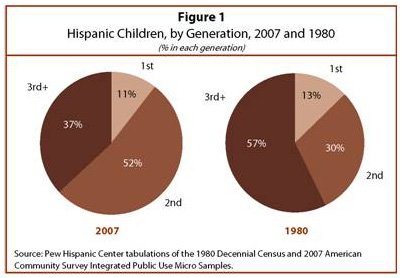

Immigration is keeping the Hispanic population foreign. As the pie charts below indicate, in 1980, 57 percent of Hispanic children were born in the US of American-born parents (third-generation children). By 2007, there had been so much Hispanic immigration and so much child-bearing by immigrants that 52 percent of Hispanic children were born of immigrant parents (second generation children) and another 11 percent had been born outside the United States (first generation children). Children of US-born parents were a minority of 37 percent.

“Assimilation” can be bad for Hispanics: US-born Hispanics have worse health habits than immigrants, and do not live as long. Those born in America are fatter, smoke and drink more, and take more drugs. The longer immigrant Hispanics live in America, the more their behavior and mortality rates begin to resemble US-born Hispanics.

Likewise, the longer Hispanics live in the United States, the more likely they are to have children out of wedlock. Children of immigrant Hispanics have a 69 percent chance of living with both parents, whereas the children of US-born Hispanics have only a 52 percent chance.

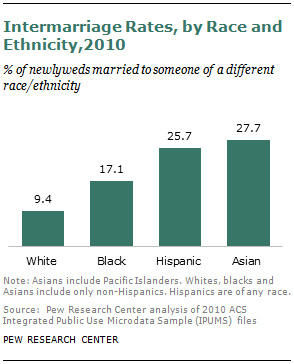

One measure of assimilation is the rate of intermarriage with people of other races. As the graph below shows, more than a quarter of marriages by Hispanics involve a non-Hispanic partner.

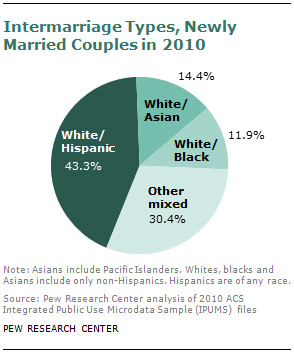

With intermarriage rates at just under 10 percent, whites are the group least likely to marry outside their race, but the pie chart below shows that white/Hispanic marriages are the most common kind of mixed marriage.

Hispanic rates of poverty, crime, disease, illegitimacy, welfare use, school failure, etc. are beyond the scope of this article, but are covered in some detail elsewhere. On the basis of attitudes alone, however, it is clear that Hispanics differ considerably from whites. It should also be clear that Hispanics are not and are never likely to be enthusiastic Republicans. It is a delusion to think that they are somehow “naturally conservative,” and are simply waiting for “outreach.” Poor Hispanics of the kind who immigrate are natural Democrats, and unless the Republicans can slash immigration levels, 2012 may be the last chance they have to elect a President.

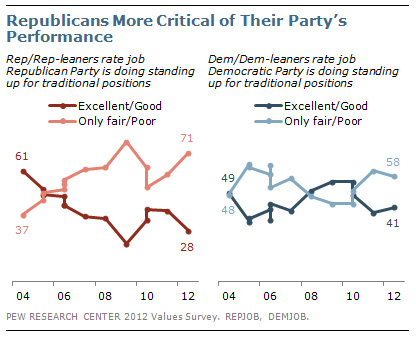

Ordinary Republicans may recognize this. As the graph below shows, dissatisfaction with their party is at near record levels. Democrats are not very happy with their party either, but they do not show the same sharp negative trend.

The current Republican presidential campaign has concentrated almost exclusively on the economy, with hardly any criticism of mass immigration or racial preferences. These are crucial questions for whites, who are the backbone of the party, but Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan are too afraid of charges of “racism” and too busy with Hispanic “outreach” to mention them, apart from vague promises to “fix a broken system,” secure the border, and increase legal immigration.

This is especially contemptible, because a campaign about the economy and unemployment cannot logically ignore immigration. Sending home millions of illegal immigrants would create jobs for Americans. Racial preferences are especially unfair when so many young people do not have jobs, but the candidates dare not say so.

Hispanics arrive as obvious recruits for the Democratic Party. Most cannot vote but their children can. As they remain here generation after generation, some of their attitudes change, but not in ways that make them less naturally Democratic. The United States is flirting with another amnesty that will only encourage more Hispanic immigrants. Even without an amnesty immigrants will continue to come unless our country takes firm action. If there really are 133 million Hispanics in the United States by mid century they will be defining what it means to be American. It will no longer make sense even to ask how well Hispanics assimilate; they will be setting the standards to which the rest of us must conform.

Primary Sources:

Pew Research Center 2012 Values Survey

Pew Hispanic Center/Kaiser Family Foundation National Survey of Latinos, December 2002

Pew Hispanic Center, 2011 National Survey of Latinos