A Voice For Our People

Peter Bradley, American Renaissance, April 2009

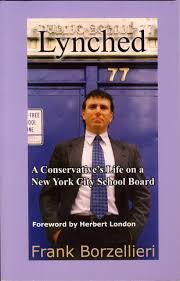

Frank Borzellieri, Lynched: A Conservative’s Life on a New York City School Board, Cultural Studies Press, 2009, 193 pp., $15.00.

From 1993 to 2004, Frank Borzellieri was a member of the District 24 school board in Queens, New York. As the only openly pro-white elected official in the United States, he was a lightning rod for controversy. His outspoken stand made him a prime target for leftist politicians, reporters, and activists but it also made him the top vote getter on the school board. Lynched: A Conservative’s Life on a New York City School Board, is Mr. Borzellieri’s account of his struggle against a hostile establishment that was determined to silence him.

In 1993, Mr. Borzellieri was living in an almost all-white Queens neighborhood but the surrounding areas were attracting large numbers of Third-World immigrants. Although he had no children of his own, the 30-year-old Mr. Borzellieri became incensed when he learned of the multi-culti nonsense being taught in schools. He ran as a complete unknown for his local school board on a platform blasting bilingual education and anti-white bias, and came in third in a field of 24 (the top nine candidates were seated). His campaign clearly appealed to ordinary voters.

Mr. Borzellieri picked his first major battle after reading the curriculum guide for students. “Entire sections of the guide were designed to have students express their feelings on ‘bigotry and racism,’ ” he writes. School-assigned reading selections would be followed by questions like ‘‘How would you have reacted to the foreman telling you that all African-American firemen were losing their jobs?”

Mr. Borzellieri issued a provocative press release stating that he would not tolerate school materials that suggested “white Europeans are to blame for all the historical troubles of man.” He also criticized a curriculum obsessed with praising the home countries of immigrants. “If I move to Pakistan, will they teach my kids about the wonders of growing up in Ridgewood, Queens?” he asked.

This press release exploded like a bomb. Newspapers attacked Mr. Borzellieri and talk show hosts invited him on their programs. There was even more outrage when Mr. Borzellieri criticized a school library for displaying a book honoring Martin Luther King right next to a book disparaging Columbus. King is beyond criticism, so the New York Civil Liberties Union, People for the American Way, and even Mayor Rudy Giuliani rushed to denounce this act of lèse majesté.

Other controversies soon followed. When Mr. Borzellieri declared that “we are a white, Christian, British, Protestant nation,” former New York City mayor Ed Koch called him “another David Duke.” The New York Daily News said he was “the devil,” and an insulting editorial about Mr. Borzellieri in New York Newsday was titled, “Mr. Whitebread.”

As Mr. Borzellieri’s public profile grew, so did opposition on the school board. The other members were almost all lefties, who usually defeated his proposals 8-1. The only other “conservative” on the board was Mary Cummins, who had made a name for herself in the 1990s by opposing the use in schools of pro-homosexual books like Daddy’s Roommate and Heather Has Two Mommies. Mr. Borzellieri quickly learned that her “conservatism” went no further than opposing militant homosexuals. She was a multiculturalism-booster and — perhaps in a bid to win friends on the left — became a fierce Borzellieri critic. He, in turn, pointed out her mushy views to conservative organizations and publications, some of which withdrew support.

Frank Borzellieri with some of the books he wanted school children to read.

One of the more amusing episodes in Lynched is the author’s description of a 1994 school board meeting that drew over 400 protesters angry over his criticisms of multiculturalism and Martin Luther King. The “liberal freak show,” as Mr. Borzellieri calls it, included followers of black supremacist Leonard Jeffries — decked out in full African garb — NAACP officials, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union Norman Siegel, and Alan Hevesi, the Comptroller of New York and second highest elected official in the city.

Mr. Borzellieri knew he would not get much time to make his case and that the implacably hostile board president would not call on any of his supporters to speak. He therefore read a strong statement that concluded with these words:

“Finally, we are tired. The Italian-Americans are tired. The German-Americans are tired. The Hungarians, Irish and Polish Americans. We are tired of racial quotas, of reverse discrimination, of not getting jobs even though we scored higher on a test. We came to America, assimilated, and learned English. We are tired of every ethnic interest group demanding its own curriculum and street signs and government forms in different languages. It was never done for any of us. Why should we do it now? We are tired of being made to feel guilty for past grievances of so-called oppressed minorities. We never asked for special privileges. Stop asking for our dollars! Enough is enough.”

This enraged the mob. For four hours more that 40 fanatics harangued the board, calling Mr. Borzellieri a bigot and a racist and comparing him to the Ku Klux Klan. Through it all, he just smiled and replied with quips that flummoxed his critics. As a police detachment called to protect Mr. Borzellieri escorted him from the board meeting, the cops told him he had their full support.

Other controversies followed, and Lynched describes them in detail. Mr. Borzellieri introduced a proclamation declaring American culture superior to foreign cultures, tried to introduce books on Paul Revere, Daniel Boone, and George Washington into school libraries, demonstrated the futility of bilingual education, and showed how tax dollars were being splashed out on special programs for non-whites even as their test scores plummeted. Mr. Borzellieri became a minor celebrity, certainly the best known school board member in New York City, with even something of a national following. He spoke at four AR conferences in a row, from 1996 to 2002, regaling audiences with his tales of fighting multicultural madness.

Mr. Borzellieri was repeatedly reelected to the school board. In the 1996 election, for example, after he had become famous, he sailed back onto the board with three times as many votes as the second-place finisher. What finally put a stop to Mr. Borzellieri’s career was a change in the system, whereby New York City abolished all local school boards.

Earlier, Mr. Borzellieri had a try at a city council seat. He won 38 percent of the vote against an incumbent — a very respectable outcome on a shoestring budget — but the money necessary to break into New York City politics at that level was simply not available. Mr. Borzellieri is now an adjunct professor of journalism at St. Johns University, also in Queens, but his involuntary departure from politics left a great void: There is no longer a single openly pro-white elected official anywhere in the United States.

Mr. Borzellieri’s adventures raise an important question. Why have no candidates followed him into office with a similar message? Even in fanatically liberal New York City there is clearly a great deal of support for someone willing to declare in public that whites should be proud of their accomplishments rather than cringe and apologize. There must be hundreds, even thousands of communities that would love to put a Borzellieri on the school board or city council. From that springboard, why not the statehouse, Congress, or even the governor’s mansion?

Nor is standing up for whites and their civilization dreary or embittering. Mr. Borzellieri clearly enjoyed every minute of it. He was never happier than when reducing his opponents to babbling idiocy.

There is no reason why there could not be Frank Borzellieris in every town and city in America, fighting for whites and their heritage. He took a stand when nobody else would. His example should be an inspiration.