Self-Segregation

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, October 2008

Bill Bishop, The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America Is Tearing Us Apart, Houghton Mifflin, 2008, 370 pp.

What happens when people have more freedom than ever to choose their associates, their churches, their news sources, their neighborhoods, and their schools? Do they seek the joys of diversity, or the company of people like themselves and ideas like their own? The answer from a racial point of view has been clear for years — Americans are essentially no less segregated than they were 50 years ago — but journalist Bill Bishop has found that we increasingly seek homogeneity that goes well beyond race. He cites convincing evidence for what he calls “the big sort:” that Americans are dividing themselves up not only geographically, but also in terms of politics, worldview, and “lifestyle,” and shutting themselves off from others. This book is yet another powerful blow against the idea that Americans (or anyone else) want diversity.

The political divide

Mr. Bishop writes that one of the sharpest and most recent divides is political, and argues that the United States has become much more partisan since a period of bipartisanship that ran from about 1948 to the mid 1960s. He writes that during that period there was much less difference between Republicans and Democrats, and few people had the ideological fervor that is common today. Only half of adults had a real understanding of what was meant by the terms “liberal” and “conservative,” and only one-third of voters could explain how the two parties differed on the most important issues of the time. Unlike today, politics had no moral dimension: No one thought his opponents were evil. Mr. Bishop notes that there was so little difference between the parties that both Republicans and Democrats tried to recruit Dwight Eisenhower as their candidate for the 1952 election, and that even as late as the early 1970s there was not much disagreement between the parties on abortion, school prayer, or women’s “rights.”

Fifty years ago Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn would serve drinks at the end of the day to the Republican leadership, and there was friendship and cooperation across the aisle. Now, according to a congressional barber who has served decades of legislators, “People don’t like each other; they don’t talk to each other.”

Mr. Bishop adds that as late as the 1980s as many as a quarter of voters were genuinely undecided and looked candidates over carefully. Now, he says, 90 percent make up their minds on the basis of party affiliation, so campaigns are designed to mobilize supporters rather than win over doubters or build consensus. Passions run so high that it is no longer unusual for party fanatics to destroy the opponents’ campaign yard signs. Younger party activists are more ideological than old hands, newly elected officials are more extreme than the ones they replace, and the women in Congress are more partisan than the men. “Compromise and cross-pollination are now rare,” writes Mr. Bishop.

Another characteristic of our times is that social clubs such as the Lions, Masons, Elks, Rotary, Moose, etc. have been losing members since the 1960s. They are broad-based groups without a political agenda, where “brothers” are likely to hold a variety of views. Now, people tend to socialize in groups with sharply defined political goals — the ACLU, the Federalist Society, the Club for Growth, EMILY’s List — and to spend hours in Internet discussions with like-minded associates.

Fifty years ago, there were not many explicitly political magazines or newspapers. Now, there is a profusion of sharply partisan print publications, and countless Internet sites that promote divergent views.

Mr. Bishop writes that this sharpening of ideological boundaries has come at a time of drastic loss of faith in traditional authorities. In the late 1950s, 80 percent of Americans said they could trust government to do the right thing all or most of the time. This faith, combined with national consensus, explains how the Johnson administration was able to pass the Great Society legislation that inaugurated the War on Poverty, Head Start, Medicare, and Medicaid. By 1976, only 33 percent of Americans trusted government, and the figure continues to sink. At the same time, Americans lost faith in doctors, preachers, universities, newspapers, and big business.

There are no simple explanations for these changes, but Mr. Bishop is convinced it has something to do with material abundance. When people are hungry they worry about survival; when survival is assured, they want self-expression. People with full stomachs question authority and act on their own political ideas rather than follow leaders. Mr. Bishop also believes that the turmoil of the 1960s — Vietnam, the counterculture, race riots, assassinations — helped destroy consensus and respect for authority, but the entire industrial world was losing faith in institutions.

Some of Mr. Bishop’s most eye-opening observations are about a recent tendency for Americans to move into and form like-minded communities. He notes that greater wealth and easier transport mean people move much more than they used to: 4 to 5 percent of the population move every year, or 100 million people in the last decade. Whether they are conscious of it or not, Americans now tend to move to areas that reflect their politics. How do we know this?

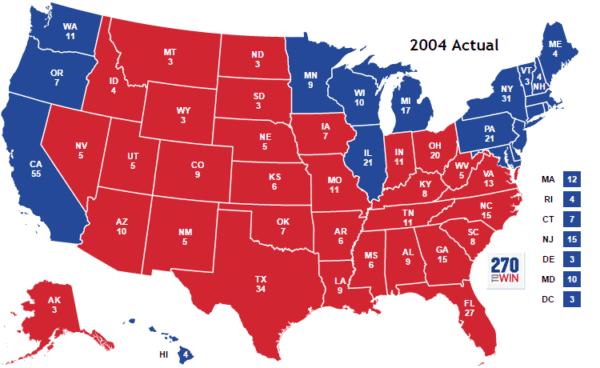

Mr. Bishop studied how every county in America voted during the last dozen or so presidential elections. He defined as “landslide counties” those in which either the Republican or the Democrat won by a margin of 20 percent or more. In 1976, 26 percent of Americans lived in such counties; by 2004, 48 percent did. To some extent, people in a county may have influenced their neighbors in one direction or another, but Mr. Bishop writes that the greatest source of increased county-level polarization is internal migration: Democrats moved out of Republican counties into Democratic counties, while Republicans did the reverse.

San Francisco County is a good example of partisan migration. In 1976, Republican Gerald Ford got 44 percent of the vote; in 2004, George W. Bush got only 15. Republicans did not all die or convert; they cleared out. Mr. Bishop offers an amusing example of the result. “How can the polls say the election is neck and neck?” he quotes a liberal. “I don’t know a single person who is going to vote for Bush.”

The same kind of sorting goes on at the state level. In 1976, either the Republican or the Democrat won by a margin of 10 percent or more in 19 states. By 2004, it was 31 states. Consistent vote patterns give rise to the shorthand of “blue” and “red” states.

Localities take on personalities that go beyond politics. Homosexuals soon learn where other homosexuals live and join them. Places such as Portland, Oregon; Austin, Texas; Raleigh-Durham; and Palo Alto, California, get reputations as trendy, yuppie, liberal havens, and attract the sort of people such places attract. An area that puts out a signal that makes the news — such as kicking out illegal immigrants or legalizing homosexual marriage — gets a national reputation that attracts more like-minded people.

Trendy, liberal places attract college-educated, creative people, and their economies thrive. Other places decline as they lose these people. In booming Austin, 45 percent of adults have a college degree. In declining Cleveland, only 14 percent do. By 2000, there were 62 metropolitan areas where fewer than 17 percent of adults were college graduates, and 32 metro areas where more than 34 percent were. That is a good gauge of an area’s dynamism.

An even better gauge is the increase (or decrease) in patents. Between 1975 and 2001, the number of patents granted to people living in Atlanta doubled. In San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle, it was up 170 percent, 175 percent, and 169 percent, respectively. Cleveland was down 13 percent and Pittsburgh was down 27 percent.

People used to move house for economic reasons. They moved to high-wage areas only if the cost of living was not so great it wiped out the wage advantage. No longer. In jazzy places such as San Francisco, New York, or Portland, housing alone is so expensive it wipes out any wage advantage, but people move anyway for the cachet and “lifestyle.” To live in certain ZIP codes is now a luxury product.

Businesses make similar calculations. They hope to recoup the higher costs of a tony address by getting better employees. This process leads to both virtuous and vicious cycles, as one place becomes Silicon Valley and another becomes Detroit. The trendy places tend to be politically liberal, and not very religious, and attract yet more people who are liberal and irreligious. Migration is self-selection.

Builders have cashed in on the desire to club with the like-minded. Mr. Bishop writes about the Ladera Ranch subdivision in Orange County, California, which has a section called Covenant Hills for religious conservatives, and Terramor for liberals. Covenant Hills has a Christian school and the architecture is traditional. Terramor has a Montessori school and the houses are trendy. Colleges have theme dormitories, not only for different races but for students who thrill to the environment or to “peace and justice.”

The political tribe

Mr. Bishop points out that the standard political profiles we take for granted today are relatively recent. He offers this contemporary cliché: anyone who drives a Volvo and does yoga is almost certainly a Democrat; anyone who drives a Cadillac and owns a gun is almost certainly a Republican. He argues that before the 1970s there were no such pat stereotypes. Today, Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to be churchgoers, but this was not so 40 years ago. Today, women vote reliably Democratic but in the 1970s women were more likely to vote Republican.

The 2004 elections offer an amusing vignette about political profiling. Mr. Bishop notes that early in the voting, exit polls suggested John Kerry would win. Why were they wrong? The poll-takers were young, collegiate-looking types who gave off a liberal aroma. They tried to stop and ask everyone how he had voted, but Republicans sized them up as Democrats and kept walking. Democrats saw them as fellow liberals and stopped to talk. Self-selection skewed the polls.

What people think about the Bible now predicts a host of other views. Fundamentalists naturally oppose homosexual marriage and abortion, but they are also likely to be for low taxes, a strong military, the death penalty, balanced budgets, and small government. They don’t like redistribution of wealth, and think jobs are more important than the environment. People who think the Bible was not divinely inspired are likely to be on the opposite side of all those issues. This does not hold for blacks, who are overwhelmingly Democrats, whether they go to church or not.

Mr. Bishop notes that there has been an association between religion and conservatism in all industrial countries but that, in most of the Western world, religion has faded. The still-strong tie in America between religion and conservatism is unusual.

The profiles of Mr. Bishop’s “landslide” counties are now no surprise to anyone, though they reflect a divide that did not exist 40 years ago. In Republican counties, 86 percent of the people are white, 57 percent are married, and half have guns in the house. In Democratic landslide counties, only 47 percent are married, only 70 percent are white, and only 19 percent have guns. The women in the different counties vary in whether they have children, how many, and how late in life they had them.

Not surprisingly, the farther people live from neighbors, the more likely they are to vote Republican. There has always been a city/country gap, but people always assumed television and the Internet would narrow it. Instead, the gap has grown wider. At the same time, with every 10 percent decline in population density, there is a 10 percent increase in the likelihood that people talk to neighbors. City people rarely do; country people almost always. The political correlation means Republicans are more likely than Democrats to talk to their neighbors. This city/country spectrum also predicts who fights our wars. In 2007, the Iraq casualty rate in Bismarck, South Dakota, was ten times that in San Francisco.

Even child-rearing is now political. Parents who require obedience and good manners tend to vote Republican, whereas indulgent parents vote Democratic. Mr. Bishop says this was not so 30 or 40 years ago, and that today, parents with the most education tend to be the most indulgent.

The Christian tribe

For three centuries, sages have been predicting the end of religion. Voltaire said it might last another 50 years. Freud, Marx, Weber, and Herbert Spencer all predicted an early death. They may have been right about most of the West, but not about America. Here, churches have survived, in part by changing to accommodate the inclination of the like-minded to herd together.

There have always been two types of Christian in America: those who thought religion was mainly a matter of personal morality, and those who thought it was an instrument for transforming society. The former — the conservatives — want to save the world by bringing more people to Christianity, whereas the latter — the liberal, “social-gospel” Christians — want to reform the world without necessarily making it more Christian.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the “social-gospel” Christians took over virtually all the mainstream Christian institutions, and used them to advance every pet liberal project from integration to homosexuality to Communism. The organized “Christian Right” emerged as a response.

Since that time, both movements have been eclipsed by a new kind of Christianity that has largely dispensed with theology, denomination, and the traditional geographic limitations on congregation size. Today, religious entrepreneurs decide where to found a church by using the same marketing and demographic techniques that determine where to put the next Wal-Mart or Home Depot. The idea is to find, within easy driving distance, a lot of people who fit a certain profile and then reach as many as possible. If the marketing is right and the preacher has flash, the result is a mega-church with a multimillion dollar budget and a TV audience. Such churches give people what they want: undemanding, feel-good Christianity, served up and consumed by people who are all the same race, social class, and political orientation.

This is far from the traditional pattern. Denominations mattered 40 years ago because Methodists and Presbyterians did not believe the same things. Also, churches served a neighborhood of people who varied, if not in race, then in many other ways. Before the “social gospel” divided churches into left and right, church members held varying political views, even if they agreed on doctrine.

Today’s nondenominational, new-breed preachers care about market share, not doctrine, and know that pushing predestination or baptism by immersion drives away customers. There are still churches with doctrine, but they count their members in the dozens or hundreds, not thousands.

Even for most mainstream churches, denomination has become so watered down it means almost nothing. As Mr. Bishop points out, whether or not a church flies the homosexual rainbow flag is a much better indication of what it is like than whether it is Baptist or Church of Christ. These days, everyone wants a tribe, and people will not cross lines of race, politics, erotic orientation, or class to go to church.

What does it mean?

“Americans,” writes Mr. Bishop, “segregate themselves into their own political worlds, blocking out discordant voices and surrounding themselves with reassuring news and companions.” He doesn’t like this tendency, because it makes Americans incomprehensible to each other. He cites often-replicated research showing that when people with off-center views spend time with each other they tend to go further off-center; lefties become more lefty and conservatives more conservative. Once a group has a distinctive tone, people gain respect and take the lead by trying to pull it even further from the middle.

Because of the self-sorting that is now common, it is possible to avoid ever having to talk to a political opponent. Many versions of the same research show that people who never meet the other side have exaggerated notions of its depravity or fanaticism. With enough reinforcement from colleagues, partisan publications, and Internet sources people can become so fixed in their thinking that they simply disbelieve anything — no matter how solidly demonstrated — that conflicts with their views.

Partisans cannot see what should be objective, common realities. For example, just before the 2006 mid-term elections, 70 percent of Republicans said the economy was doing fine, while 75 percent of Democrats said it was in deep trouble. Even if they have different news sources, Democrats and Republicans must see the same economic statistics.

This tendency to let party loyalties warp their vision is consistent with another finding by political scientists: Many people choose a party more for psychological than political reasons. Mr. Bishop quotes sociologist Paul Lazarfeld: “It appears that a sense of fitness is a more striking feature of political preference than reason and calculation.” People pick parties if they fit in socially; policy is secondary.

Mr. Bishop adds that people sometimes switch parties when their politics change, but that it is more common to change opinions to match the party consensus. Being a Democrat or Republican means joining a family or adopting a way of life as much as it reflects political choice.

Shrewd political operators have always understood the importance of conformity and belonging. They try to choose canvassers or precinct walkers so that when someone comes to your door he is not only your race and social class, but your neighbor. Emotion and loyalty drive politics more effectively than calculation.

What are the political consequences of “the big sort”? Mr. Bishop argues that Congress is often deadlocked because hard-liners refuse to compromise. When Congress won’t act, the President and the courts take over, but so do local governments. Local autonomy is seeing a resurgence as states and cities deal unilaterally with illegal immigration, homosexual marriage, race preferences, abortion, smoking bans, stem-cell research, etc. Heightened partisanship paralyzes Congress while, at the same time, building homogenous local majorities that can pass laws that would be unthinkable in another state or county. Local majorities, both liberal and conservative, are rehabilitating states’ rights.

Possibilities

Local majorities have already passed laws that send clear signals to racially conscious whites. “Sanctuary cities” are not attractive while cities that require police to enforce immigration law are. For the time being, these signals are not explicitly racial, but if the country really is drifting toward increased polarization, eventually there will be localities that consistently pass laws that have the effect of protecting white majorities and white institutions.

Today, laws cannot be explicitly racial, but they don’t have to be. A city or town that affirms a policy of hiring on merit alone or a school district that mentions crime rates during Black History Month will attract certain people and repel others. Measures do not need to be dramatic to reverse current demographic flows; reputation alone can set virtuous cycles in motion.

Within the two-party system, it is very difficult to make progress at the national level. Local politics, especially in a time of increased sorting, has much more potential. Once a town or county were secured, it could both lead by example and provide a base for state-level action. Voluntary sorting works in our favor. It is up to us to channel and use it for larger, long-term purposes.