The Racial Revolution

Jared Taylor, American Renaissance, May 1999

Everyone knows that during the last 50 years or so there have been fundamental changes in the ways Americans think about race. In fact, what has occurred is nothing short of a revolution, a complete rejection of what earlier generations of Americans — from Colonial times until perhaps the 1950s — took for granted.

Although contemporary racial thinking is so monolithic it has become hard to imagine how Americans could have thought otherwise, we can get a sense of how radical the change has been if we try to imagine equally far-reaching changes: What would it be like for America to reverse the sexual revolution completely and return to Victorian propriety in just a few generations? Or for a country suddenly to stop being deeply and universally religious and become atheist? Or to abandon the principle of private property and switch to hippy-style communal living?

The United States has gone through a revolution that is not only just as dramatic, but astonishing in another respect: What was once taken for granted about race has become not just outmoded but immoral. Only revolutions bring such sweeping, back-to-front moral changes.

Yesterday’s Assumptions

The best way to gauge the extent of the revolution is to compare the present to the past. The contrast is staggering. Practically every historical American figure was by today’s standards an unregenerate white supremacist.

Until just a few years ago virtually all Americans believed that race was a profoundly important aspect of individual and national identity. They believed that people of different races differed in temperament and ability, and that whites built societies that were superior to those built by non-whites. They were repelled by miscegenation — which they called “amalgamation” — because it would dilute the unique characteristics of whites. They took it for granted that America must be peopled with Europeans, and that American civilization could not continue without whites. Many saw the presence of non-whites in the United States as a terrible burden.

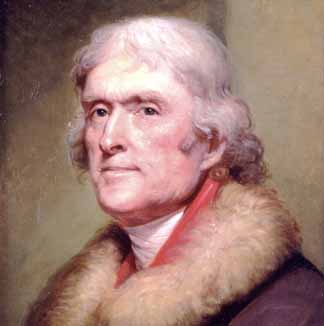

Among the founders, Thomas Jefferson wrote at greatest length about race. He thought blacks were mentally inferior to whites, and though he thought slavery was a great injustice he did not want free blacks in American society: “When freed, [the Negro] is to be removed beyond the reach of mixture.” Jefferson was, therefore, one of the first and most influential advocates of “colonization,” or sending blacks back to Africa.

He also believed in the destiny of whites as a racially conscious people. In 1786 he wrote, “Our Confederacy [the United States] must be viewed as the nest from which all America, North and South, is to be peopled.” In 1801 he looked forward to the day “when our rapid multiplication will expand itself . . . over the whole northern, if not the southern continent, with a people speaking the same language, governed in similar forms, and by similar laws; nor can we contemplate with satisfaction either blot or mixture on that surface.” The empire was to be homogeneous.

Jefferson thought of the United States as only the latest outpost in the ever-expanding march of the Anglo-Saxon, the Saxon branch of which had originated in the Cimbric Chersonesus of Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein. He was thinking of the Saxons when he proposed a 1784 ordinance to create new states in the Mississippi valley, suggesting the name Cherronesus for the area between lakes Huron and Michigan. Its shape reminded him of Denmark. The race was not to forget its origins.

James Madison, like Jefferson, believed the only solution to the race problem was to free the slaves and send them away. He proposed that the federal government sell off public land to raise the huge sums necessary to buy the entire black population and ship it overseas. He favored a Constitutional amendment to establish a colonization society to be run by the President. After his two terms in office, Madison served as president of the American Colonization Society, to which he devoted much time and energy.

The following prominent Americans were not merely members but officers of the society: Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Stephen Douglas, William Seward, Francis Scott Key, Gen. Winfield Scott, and two Chief Justices of the Supreme Court, John Marshall and Roger Taney. As for James Monroe, the capital of Liberia is named Monrovia in gratitude for his help in returning blacks to Africa.

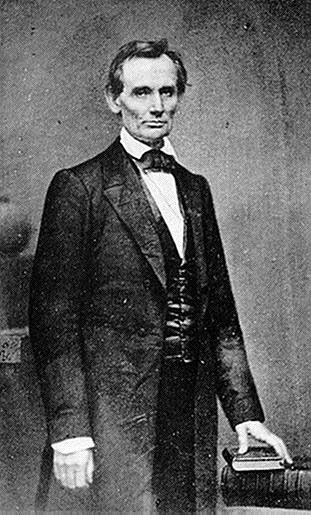

Abraham Lincoln considered blacks to be — in his words — “a troublesome presence” in the United States. During the Lincoln-Douglas debates he said:

. . . I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will for ever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be a position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.

He, too, favored colonization and even in the midst of a desperate war with the Confederacy found time to study the problem and to appoint Rev. James Mitchell as Commissioner of Emigration. Free blacks were going to have to be dealt with, and it was best to plan ahead and find a place to which they could be sent.

Abraham Lincoln

Before Lincoln’s time, no President had ever invited a group of blacks to the White House to discuss public policy. On August 14th, 1862, Lincoln did so — to ask blacks to leave the country. “There is an unwillingness on the part of our people, harsh as it may be, for you free colored people to remain with us,” he explained. He then urged them and their race to go to a colonization site in Central America that his Commissioner of Emigration had investigated. Later that year, in a message to Congress, he even argued for the forcible removal of free blacks.

His successor, Andrew Johnson, did not feel differently: “This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men. . . .” Like Jefferson, he thought whites had a clear mandate: “This whole vast continent is destined to fall under the control of the Anglo-Saxon race — the governing and self-governing race.”

Before he became President, James Garfield wrote, “[I have] a strong feeling of repugnance when I think of the negro being made our political equal and I would be glad if they could be colonized, sent to heaven, or got rid of in any decent way. . . .”

What of 20th century Presidents? Theodore Roosevelt thought blacks were “a perfectly stupid race,” and blamed Southerners for bringing them to America. In 1901 he wrote: “I have not been able to think out any solution to the terrible problem offered by the presence of the Negro on this continent . . . he is here and can neither be killed nor driven away. . . .” As for Indians, he once said, “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn’t inquire too closely into the health of the tenth.”

William Howard Taft told a group of black college students, “Your race is adapted to be a race of farmers, first, last and for all times.”

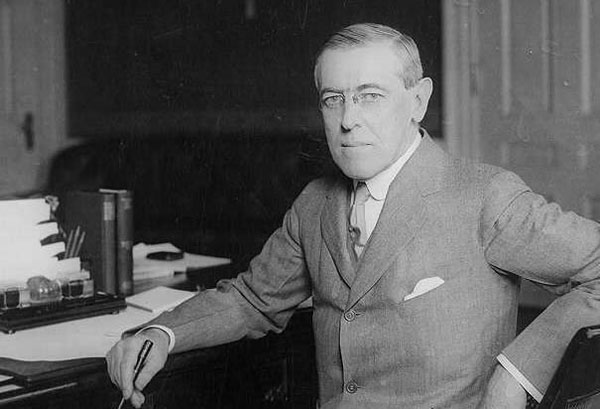

Woodrow Wilson was a confirmed segregationist, and as president of Princeton prevented blacks from enrolling. He enforced segregation in government offices and was supported in this by Charles Eliot, president of Harvard, who argued that “civilized white men” could not be expected to work with “barbarous black men.” During the Presidential campaign of 1912, Wilson took a strong position in favor of excluding Asians: “I stand for the national policy of exclusion. . . . We cannot make a homogeneous population of a people who do not blend with the Caucasian race. . . . Oriental coolieism will give us another race problem to solve and surely we have had our lesson.”

Woodrow Wilson

Warren Harding’s views were little different: “Men of both races may well stand uncompromisingly against every suggestion of social equality. This is not a question of social equality, but a question of recognizing a fundamental, eternal, inescapable difference. Racial amalgamation there cannot be.”

Henry Cabot Lodge took the view that “there is a limit to the capacity of any race for assimilating and elevating an inferior race, and when you begin to pour in unlimited numbers of people of alien or lower races of less social efficiency and less moral force, you are running the most frightful risk that any people can run.”

In 1921, as Vice President-elect, Calvin Coolidge wrote in Good Housekeeping about the basis for sound immigration policy: “There are racial considerations too grave to be brushed aside for any sentimental reasons. Biological laws tell us that certain divergent people will not mix or blend. . . . Quality of mind and body suggests that observance of ethnic law is as great a necessity to a nation as immigration law.”

Congressman William N. Vaile of Colorado was a prominent supporter of the 1924 immigration legislation that set policy until the revolution of the 1960s. He explained his opposition to non-white immigration this way:

Nordics need not be vain about their own qualifications. It well behooves them to be humble. What we do claim is that the northern European, and particularly Anglo Saxons made this country. Oh yes, the others helped. But that is the full statement of the case. They came to this country because it was already made as an Anglo-Saxon commonwealth. They added to it, they often enriched it, but they did not make it, and they have not yet greatly changed it. We are determined that they shall not. It is a good country. It suits us. And what we assert is that we are not going to surrender it to somebody else or allow other people, no matter what their merits, to make it something different. If there is any changing to be done, we will do it ourselves.

Harry Truman is remembered for having integrated the armed services by executive order. Yet, in his private correspondence he was as separatist as Jefferson: “I am strongly of the opinion Negroes ought to be in Africa, yellow men in Asia and white men in Europe and America.” In a letter to his daughter he described waiters at the White House as “an army of coons.”

As recent a President as Dwight Eisenhower argued that although it might be necessary to grant blacks certain political rights, this did not mean social equality “or that a Negro should court my daughter.” It is only with John Kennedy that we find a President whose public pronouncements on race begin to be acceptable by contemporary standards.

Politicians usually express careful, non-controversial views, and their sentiments were reflected by men of letters as well. Ralph Waldo Emerson, for example, believed that “it is in the deep traits of race that the fortunes of nations are written.” Walt Whitman wrote: “Who believes that Whites and Blacks can ever amalgamate in America? Or who wishes it to happen? Nature has set an impassable seal against it. Besides, is not America for the Whites? And is it not better so?” Jack London was a well-known socialist, but he did not think socialism was universally applicable. It was, he wrote, “devised for the happiness of certain kindred races. It is devised so as to give more strength to these certain kindred favored races so that they may survive and inherit the earth to the extinction of the lesser, weaker races.” Mark Twain, in an essay that no longer appears in popular anthologies, once described the American Indian as “a fit candidate for extermination.”

There is essentially no limit to the “racist” quotations one could unearth from prominent Americans of the past, but views that are considered unacceptable by today’s standards were so widespread that virtually anyone who said anything about race reflected those views.

Needless to say, this embarrasses today’s guardians of orthodoxy. Most historians ignore or gloss over the racial views of prominent figures, and most people today have no idea Lincoln or Roosevelt were such outspoken “white supremacists.” Some people deliberately distort the views of great Americans. For example, inscribed on the marble interior of the Jefferson Memorial are the words: “Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people [the Negroes] shall be free.” Jefferson did not stop there, but went on to say, “nor is it less certain that the two races equally free, cannot live under the same government” — which rather changes the effect.

Thomas Jefferson

Another approach to Jefferson is to bring out all the facts and then try to repudiate him. Conor Cruise O’Brien did this in a 1996 cover story for Atlantic Monthly. After describing Jefferson’s views, he writes:

It follows that there can be no room for a cult of Thomas Jefferson in the civil religion of an effectively multiracial America — that is, an America in which nonwhite Americans have a significant and increasing say. Once the facts are known, Jefferson is of necessity abhorrent to people who would not be in America at all if he could have had his way. Richard Grenier agrees, likening Jefferson to Nazi Gestapo chief Heinrich Himmler, and calling for the demolition of the Jefferson Memorial ‘stone by stone.’

It is all very well to wax indignant over Jefferson’s views 170 years after his death, but if we start purging American history of “racists” who will be left? If we demonize Jefferson we have to repudiate everything that happened in America until the 1960s — which is precisely what the revolution in racial thinking logically requires.

After all, until 1964, any employer could refuse to hire non-whites and merchants could refuse to do business with whomever they pleased. Until 1965, immigration laws were designed to keep the country white. In 1967, when the Supreme Court ruled them unconstitutional, 20 states still had anti-miscegenation laws on the books. State legislatures were unwilling to repeal laws that reflected the customs and ideals of generations of Americans.

The Revolution

So how does a society handle a revolution that turns the common sense of previous eras on its head? One thing that changes is language. Because the thinking of men like Lincoln and Wilson was so widespread, there was no need for a special term to describe it. Just as there is no word to describe only those days on which the sun rises — because it rises every day — there was no word to describe people who thought of race the way they did.

The word “racism,” therefore, did not appear until the 1930s, and was a description not of American thinking but of Nazi ideology. Only in the 1960s did the word become common in its current usage, and as late as 1971, the Oxford English Dictionary had no entry for it. We managed to establish slavery, abolish it, establish Jim Crow, and abolish it too without ever using a word that today’s newspapers find indispensable. When our ancestors wrote about race, they wrote of antagonism, kindness, hostility, admiration, hatred, and a host of other feelings, but never about “racism.” The word does not appear even in so late and influential a book as Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma, published in 1942. Only in the context of mid-20th century assumptions did the word become necessary as a way to condemn what people had always taken for granted.

Even the word’s predecessor, “racial prejudice” is a recent construction (it is the term Myrdal used). Whatever Abraham Lincoln or Theodore Roosevelt thought about other races, they would have been insulted to be told it was prejudice, that is to say, unreasonable preconceived judgment. “Racial prejudice” was a particularly clever coinage because it implied that white attitudes were a form of ignorance that could be cured with proper education. It managed to discredit while appearing to describe.

What Americans traditionally practiced was racial discrimination, that is, they made distinctions. Choice and freedom are impossible without discrimination, and a “discriminating man” is one who knows the differences between things and chooses wisely. Discrimination — the most necessary and natural thing people do — is now called “bigotry.”

The very newness of terms like “racism” and “racial prejudice” is reason enough to be suspicious of them. To define a serious moral failing with words that did not even exist in the time of our grandparents is not a sign of normal social change. It is panic and hysteria.

The race revolution has been like the Russian revolution, which also stood common sense on its head. In the Soviet Union the profit motive, which had been the driving force of every economy in history, became a sin against the people, and new words had to be invented for new crimes. People who still believed in private property had a “petty bourgeois mentality.” Those who wanted to keep what they made were “stealing from the state.” Anyone who defended free markets was a “stooge of imperialism.” After the fall of Communism common sense was rehabilitated, and all the new crimes and words to describe them disappeared.

Ironically, during the years that led to the return of common sense in the former Eastern Bloc, the reverse process continued in the West. “Racism” was such a success it inspired the discovery of all sorts of new crimes: sexism, lookism, ableism, speciesism, male chauvinism, homophobia, nativism, etc. One natural, healthy distinction after another was discovered to be a crime. It must be a uniquely 20th century experience for large numbers of people to be accused of crimes for which the very words to describe them have only just been invented.

Rules for Whites

So what is racism, anyway? For whites (and only for whites), it is anything that deviates from the following principles: Race is an utterly insignificant matter. It means nothing, explains nothing, and stands for nothing. The races are not only equal, they are interchangeable. Therefore, it makes no difference if the neighborhood turns Mexican or the nation turns non-white or your children marry Haitians. For whites, race is not a valid criterion for any purpose, and any decision they make on the basis of race is immoral. For whites to take notice of race at all is “racism.”

Of course, this contradicts one of the current myths about America, that racial diversity is one of our great strengths. If the races are equivalent, how can racial diversity have any meaning at all? For racial diversity to be a strength (or a weakness or be noticed at all) race must have some kind of meaning, and to the extent that race stands for something why is it wrong for whites to take race seriously both in their personal lives and political views?

The benefits of racial diversity are now supposed to be so important that they justify “affirmative action,” or racial discrimination against whites. If racial diversity is that valuable, race has to mean something significant. But if race is both real and important, why is it wrong to notice and care about these meanings? Why is it wrong for whites to find these differences not to their liking?

Presumably, the theory is that although races are essentially equivalent and interchangeable, blacks, for example, have had different experiences from whites, and whites benefit from contact with the different “culture” blacks have acquired. This doesn’t explain why whites must be forcibly brought into contact with this “culture.” And if it is so different from white culture that “affirmative action” must be resorted to in order to expose whites to it, some whites will find that they don’t like it all, and decide they want nothing to do with it.

The real, unspoken explanation for why diversity is a strength is that race is in fact meaningful. Diversity exposes whites to superior people and superior ways of thinking. After all, sermons about diversity are directed only at whites. Bringing non-whites onto campus or into the club is supposed to be improving and edifying for whites, not for non-whites.

In fact, the idea that whites are inferior, or at least deeply and uniquely flawed is the one distinctly racial idea whites are allowed to have about themselves. Outside the underground “racialist” press it is impossible to find whites portrayed in positive terms as a race. In the past 30 years, probably no mainstream public figure or commentator has expressed pride or satisfaction in being white or urged other whites to do so. On the contrary, in any discussion of race, it is obligatory to write disparagingly about whites, to remind them of past and present crimes, to make them ashamed to be white. Most of the time, whites are supposed to believe that race is simply an empty category, but if they are to have one explicitly racial sentiment about themselves, it is shame.

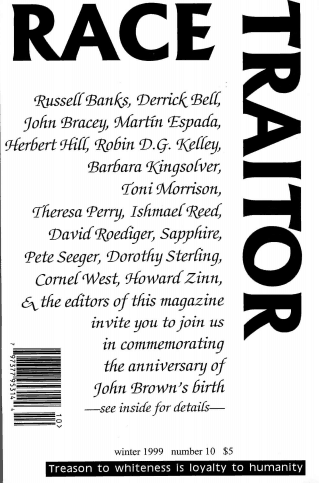

“The white race is the cancer of human history,” says Susan Sontag. “Treason to whiteness is loyalty to humanity,” says Noel Ignatiev of Race Traitor magazine. He wants to “abolish the white race — by any means necessary.” Christine Sleeter writes that “Whiteness . . . has come to mean ravenous materialism, competitive individualism, and a way of living characterized by putting acquisition of possessions above humanity.” This is presumably this sort of thing President William Clinton’s daughter, Chelsea, was supposed to think about when her high school had her write an essay called “Why I am Ashamed to be White.” The text book for teacher training reviewed in the previous issue of AR is packed with creative ideas about how to make whites apologize for their race and for their very existence.

The black author James Baldwin once wrote that any white person who wants to have real dialogue about race must start with a confession that is nothing short of “a cry for help and healing.” Perhaps columnist Maggie Gallagher was crying for help when she wrote that she thinks of herself as an American, a Catholic, and sometimes an Irish-American but added, “I hate the idea of being white. . . . I never think of myself as belonging to the “white race.’ Those who do, in my experience, are invariably second-raters seeking solace for their own failures. I can think of few things more degrading than being proud to be white.”

For almost all whites, the only time they ever speak as whites is to apologize. President Clinton is typical. When he speaks as a white man it is to apologize for the Tuskeegee medical experiment that left black men untreated for syphilis or to apologize for slavery.

The celebration of Martin Luther King’s birthday is an orgy of white apology. King spent his life telling whites they were wrong. This is now thought to be so valuable a role that it makes no difference that he was a plagiarist, adulterer, and communist sympathizer. For having succeeded in persuading so many whites that they were wicked he has now eclipsed George Washington as America’s most honored secular saint. Only whites could make a hero of a man who spent his life denouncing them.

The Final Solution

So where has the revolution brought us? Whites are to pretend that race is meaningless. They have no legitimate group aspirations. Racial diversity is a good thing if it comes at the expense of whites. Slavery is a crime for which we — and only we — must be forever guilty. The conquest of the continent was not the expansion of civilization but a rape and an abomination. We have no claim to this land, but must let in every band of Third-Worlders who have wrecked their own countries and who will cheerfully wreck ours. If we believe the propaganda of the last 50 years, we must rethink and abandon virtually everything about America. Whites are a uniquely wicked race, and the sooner we are shoved aside by virtuous non-whites the better.

Once more, we can rely on President Clinton to show us the way. He says that after independence from England and the War Between the States, the reduction of whites to a minority will be “the third great revolution of America.” He looks forward to the challenge of seeing “if we can prove that we literally can live without having a dominant European culture.”

Rosa Parks with Bill Clinton

Former Republican congressman Robert Dornan of California agrees. In 1996, while he was still in the House, he said, “I want to see America stay a nation of immigrants. And if we lose our Northern European stock — your coloring and mine, blue eyes and fair hair — tough!” In his next election, he lost to a Hispanic, Loretta Sanchez. This is exactly what Mr. Dornan’s cheerfulness about immigration should have prepared him for — his constituency had rapidly become half Hispanic — but apparently it did not. He refused to concede defeat and charged Miss Sanchez’ supporters with vote fraud. He has not, however, changed his position on the advisability of whites becoming a minority.

And it’s not just Americans who happily look forward to oblivion. Gwynne Dyer, a London-based Canadian journalist, takes for granted that “ethnic diversification” is a good thing for white countries, but notes that Canada and Australia, which have opened their borders to non-white immigration, are trying to “do good by stealth.” Politicians understand the advantages of diversity but think they must not let ordinary whites know what is happening: “Let the magic do its work, but don’t talk about it in front of the children. They’ll just get cross and spoil it all.” Being reduced to a minority will be good for whites but the prospect must be kept secret from them for fear they might object. Miss Dyer looks forward to the day when politicians can be more open about displacing their own people.

Pauline Hanson is the famous Australian politician who doesn’t want whites to become a minority. Such a view is “racist,” of course, and an Australian writing in the Washington Post describes the people for whom Miss Hanson speaks as “the beast,” which is “alive and well, slimily squirming.” No doubt these loathsome forces will be vanquished. The Chicago Tribune gave an article about Miss Hanson the sub-headline: “A new, anti-immigrant party appeals to some Australians who still harbor notions of remaining a Caucasian society.” Fancy that: There are still a few Australians who “harbor the notion” that their country should stay white.

Of course, reducing whites to a minority is only a good first step; with enough interracial marriage, whites might be made to disappear completely. It has therefore become increasingly common to propose miscegenation as the final solution to the race problem. “It would be a lot easier if each of us were related to someone of another color and if, eventually, we were all one color,” writes Morton Kondracke in The New Republic; “In America, this can happen.” “I think intermarriage may be the only way out [of our racial problems],” writes Jon Carroll of the San Francisco Examiner. Ben Wattenberg, noting the increase in interracial marriages writes happily, “Does all this mean that as we move into the next century race will be much less of an issue? That we will all end up bland and blended? That (as I believe) we will fulfill our difficult destiny as the first universal nation?”

Even “conservatives” think intermarriage is the answer. Douglas Besharov of the American Enterprise Institute says it may be “the best hope for the future of American race relations.” In a recent book, Stephen and Abigail Thernstrom write that the “crumbling of the taboo on sexual relations between the two races [black and white]” is “good news,” because that will make it impossible to draw racial distinctions.

John Miller is a reporter for National Review, which is thought to be the main “conservative” magazine in America. He thinks miscegenation is inevitable and could be the only way to end racial tension. “Perhaps the best way to undermine the ideology of group rights is to permit this natural process of assimilation to work its way down the generations as people of mixed background marry and have children.” “In the future,” he adds confidently, “everyone will have a Korean grandmother.” This is the happy ending. As they become a minority, whites will dissolve into a glorious, café au lait.

Not only was this the very reverse of what the founders had in mind, it was not even what the racial activists of just a few decades ago had in mind. The post-1965 changes in immigration policy were not supposed to upset the ethnic balance. The civil rights movement was supposed to usher in a new Camelot of racial understanding and harmony. Both predictions were dead wrong: the percentage of whites is shrinking and scarcely anyone pretends that race relations are good. What do we do? Just toss the whole country into a blender and do away with race entirely. Of course, this really means doing away with whites. Whites are only about 15 percent of the world’s population and are having perhaps seven percent of the world’s babies. No one is proposing the blender treatment for Africa or Asia.

It is only whites who have been stripped of any intellectual defenses against this final solution. Race is a forbidden criterion — at least for their purposes — and whites are a shameful bunch anyway. A people whose only collective sentiment is guilt might as well fade away. We have come a long way from Jefferson’s vision of Europeans filling the Americas from north to south.

Pierre Vergniaud (1753–1793) was a French lawyer and revolutionary politician who, like so many others, ended up on the guillotine. It was he who said that the revolution “might devour each of its children in turn.” Ours has been a revolution that, if left unchecked, will certainly devour our children.

However, revolutions that violate the laws of human nature eventually founder. Some day ours will collapse, as biology reasserts itself over sociology, and white racial consciousness reawakens. The Soviet Union staggered on for 75 years before its revolution collapsed under its own weight. The racial revolution has been in full swing for 50 years, and its absurdities and contradiction have never been more evident.

[Editor’s Note: This essay is in A Race Against Time: Racial Heresies for the 21st Century, a collection of some of the finest essays and reviews published by American Renaissance. It is available for purchase here.]