Shifting Alliances: Black, Red, and White

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, September 30, 2021

Joseph Ford Cotto, Runaway Masters: A True Story of Slavery, Freedom, Triumph and Tragedy Beyond 1619 and 1776, 2021, 193 pp., $9.99 (softcover)

The struggle for power is eternal, but alliances are not. Tribes, nations, and races rise and fall, and there is no permanent villain or hero. Sometimes, there’s neither right nor wrong, but simply “us” and “them” — but defining “us” and “them” is not always easy. A group’s culture, identity and status can change because identity isn’t only biological, but the result of historical forces and the battle for power.

Joseph Cotto’s Runaway Masters, a history of the Seminoles, is a reminder of this. American Renaissance readers may know Mr. Cotto from the Cotto/Gottfried podcast with Paul Gottfried. He has a particular interest in shifting identities. His previous book, Under the Crown and Stripes, described exiled royals in the United States. It earned him a hereditary barony from King Kigeli V of Rwanda.

Mr. Cotto’s style is casual — almost breezy — and Runaway Masters tells a fast-paced story with the energy of battlefield reports. It is a history of the war of white, black, and red, but it’s not about a simple race war. Allegiances changed quickly, as each group pursued its interests, leading to wars between and within races and nations.

Seminoles are a storied part of Florida history. The Washington “Redskins” may be gone, but the Florida State Seminoles remain. Among other tributes, Florida named a county, city, and lake after the Seminoles. “[W]hite Americans keeping Indian names for various settlements and naming almost any entity imaginable after certain tribes, chiefs, and warriors,” Mr. Cotto notes, “indicates the esteem in which red society was, and is, held.”

The Seminoles were Creeks who migrated south in the 1700s; their name is a clumsy Anglicization of “runaway.” One could argue that Seminoles are less rooted to their land than New Englanders of Mayflower stock or Afrikaners in the Cape.

Spain nominally owned Florida before the American Revolution but was too weak to control the Seminoles. “[W]hite was effectively at the mercy of red,” writes Mr. Cotto, “while blacks found themselves as slaves to white and red alike.”

The rapid changes of fortune that arose later are due to the kind of people who came to Florida. American settlers and their great champion General Andrew Jackson were fighters. The Seminoles, unlike their Creek cousins among the “civilized” tribes, ruled over territory much as the Mongols did. Instead of building cities or clearing plantations, they moved often, hunting wherever they pleased. The blacks under Seminole rule were technically slaves and had to pay tribute and supply food as their masters required. Other than that, they could farm their own land and were pretty much left alone.

The blacks who became the “Seminole Negroes” were mainly runaways from American states. They had weapons and some self-rule, and it is better to think of them as vassals. They preferred Seminole slavery to working on white-run plantations. They copied Seminole dress and customs, but they had their own interests. White Americans could sometimes divide reds from blacks.

The Spanish Empire’s weakness led to frequent wars over Florida. National loyalties were fragile. For example, General James Wilkinson, for a time the most powerful military official in the early United States, was a Spanish spy and a traitor. Border territories, where sovereignty is unclear, breed such men, and the loyalties of mixed-race people can be even more complex.

A major Creek chief just after American independence was Alexander McGillivray, son of a Creek woman and a Scotch trader. He supported the British during the Revolution, represented the Creeks and Seminoles during negotiations with the Spanish, and occasionally worked for the new United States. “So this very remarkable Indian chief had held high commissions under three great civilized nations,” wrote historian Caroline Mays Brevard. “He died in 1793, and was buried at Pensacola with Masonic honors.”

Perhaps the greatest Seminole leader, Osceola, was one-quarter white, but was so loyal to his land and people that he killed a Seminole chief who, unlike Osceola, was willing to move West. There is a pattern here. The Comanche chief Quanah Parker was the half-white son of an Indian and a kidnapped white woman. Like Malcolm X, these racially mixed men were hostile to whites.

Great Britain, after once controlling Florida, sold it back to Spain in 1783. The weak Spanish Empire welcomed runaway slaves to Florida because they were a buffer against land-hungry white Americans. However, the Seminoles in Florida did not welcome blacks. They enslaved them, but treated them better than Southern plantation overseers.

Osceola had a typical view of blacks. When a federal Indian agent told him that the Seminole couldn’t buy any more gunpowder — a rule that had hitherto applied only to blacks — he reportedly said: “Am I a negro? Am I a slave? My skin is dark, but not black, I am an Indian, a Seminole!”

Osceola, 1838. (Credit Image: © Mary Evans via ZUMA Press)

The blacks were mostly left alone if they paid tribute, but white Americans saw Florida as a potential base for blacks. If the blacks ever gained control over the Seminoles, whites feared another Haiti. Furthermore, escaped slaves were American property, and owners wanted them back.

For territorial and racial reasons, white frontiersman founded the “Republic of Florida” in 1812, with the help of a few American troops. When the Spanish complained and the Seminoles fought back, President James Madison withdrew support and the republic collapsed. The “revolution,” Mr. Cotto says, accomplished nothing.

The flag of East Florida.

At the outset of the War of 1812, the legendary Indian chief Tecumseh incited Indians against white settlers. The British occupied Pensacola and trained Indians as British soldiers. Spain couldn’t stop this, so it backed the British effort; white Americans — not Britain — were the real threat to Spanish control of Florida.

Andrew Jackson raised an army and drove the British out of Pensacola, but they didn’t give up. In 1814, two British officers armed slaves and Indians against white Americans. One officer, Edward “Fighting” Nicolls, an abolitionist, recruited some of the Seminoles’ black slaves by offering them freedom. Nicolls built a fort at “Prospect Bluff” and filled it with blacks and some Creeks from Alabama. They continued to hold the fort even after the War of 1812 ended. Worse, they began raiding American plantations.

The black-Creek alliance split when an American agent offered the Indians protection. Most of them left what then became known as the “Negro Fort.” The political situation was murky. Florida was still technically Spanish territory, but the blacks at the “Negro Fort” said they were defending British territory. Seminoles wanted their slaves back. Pro-slavery Creeks wanted to plunder the fort. White Americans wanted to destroy the fort to stop black raids and to keep runaways from having a base.

Jackson decided to take the fort, even though it meant violating Spanish sovereignty. In 1816, the United States illegally sent warships through Spanish rivers. Blacks ambushed and killed a small foraging party, and even burned one American alive.

A joint American-Creek force then used cannon against the fort. One ball that was heated before firing (a “hot shot”) scored a hit on the powder magazine and blew up the fort. The victorious army executed the fort’s commander, an ex-slave who fought under the British flag.

The battle at the “Negro Fort” was the beginning of the First Seminole War, which lasted until 1819. Americans and Creeks developed closer ties because they had a common interest in maintaining slavery, and wanted to move into Seminole lands. There is evidence that Great Britain supported the Seminoles. One Seminole chief, Enemathla, allegedly had a British uniform and had sworn loyalty to the Crown.

Andrew Jackson led a joint force of Americans and Creeks in an illegal invasion of Spanish-owned Florida. “[I]t was obvious that the Seminole had never met a more determined foe than Jackson, nor had Jackson encountered anyone quite like the Seminole,” Mr. Cotto writes. “Each was in a war for the survival of his own people, with only the greatest will to be named the victor.”

Andrew Jackson and the Creek Indian Red Cloud. Credit: Zuma Album / Oronoz

This was not a war of whites against Indians. White Americans and Creeks fought against Seminoles (who were a breakaway faction of Creeks). Even the “Creeks” and “Seminoles” included groups and tribes that did not always align in expected ways. The Seminoles’ black slaves fought for their masters because it was better than slavery on an American plantation.

Jackson defeated the Seminoles, the United States acquired Florida, and Andrew Jackson became governor. In 1823, the Americans and Seminoles signed a treaty that gave the latter protection but limited them to a reservation.

The Seminoles then put their own survival over black interests and turned over their slaves, who were supposed to return to plantation slavery in the United States. Many fled to the Bahamas, but several hundred managed to stay with the tribe in a legal gray zone, establishing their own hybrid culture with Seminole, British, and African influences.

These complex alliances show that the conquest of North America was not always a story of united whites defeating non-whites. Ultimately, however, it was a racial battle.

In 1824, Enemathla, who had fought with British support against the United States in the First Seminole War, told his people not to withdraw to the land set aside for them by the treaty. “When I was a boy, the Indians still roamed undisputed . . . and now, when there is nothing left them but their hunting grounds in Florida, the white men covet that,” he supposedly said. “I tell you plainly, if I had the power, I would tonight cut the throats of every white man, woman, and child in America.”

Enemathla understood the consequences of wars and population transfers. Indian leaders were right to fear and fight white settlers.

Whites had numbers on their side, but they also had courage. William Duval, the first civilian to govern Florida, bravely walked into a Seminole meeting and listened to Enemathla whip up his warriors. Suddenly, he grabbed Enemathla by the throat, called him a traitor, and threw him out of the room. He then told the Seminole to honor their promise to stay on the reservation. The “Great White Father” would avenge any harm against whites, he said. Cowed by their leader’s humiliation, the Seminole complied — for a time.

William Duval

After Andrew Jackson became president in 1829, the administration decided to move the Seminole to the West. The part-white Osceola, not yet a chief, listened to an American agent’s newest proposal. Osceola drew his knife, stabbed it into the table, and swore that he would hold the United States to its agreement to let the Seminole stay in Florida.

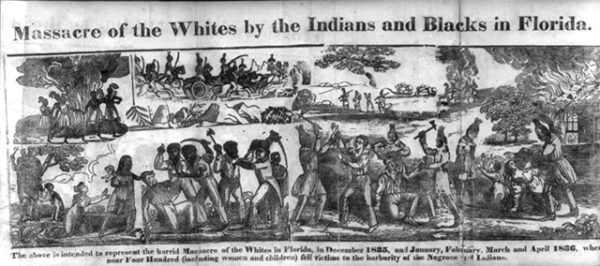

Some Seminole chiefs had been tricked or coerced into signing treaties agreeing to move west, but many Seminoles refused to leave their land. As the federal government prepared for the move, Fort King in north-central Florida became its main base of operation. On December 28, 1835, Major Francis Dade and 110 soldiers were reinforcing the fort when 180 Seminoles ambushed them, killing all but three, in what became known as the “Dade Massacre.” The same day, Osceola killed an Indian agent named Wiley Thompson, and the Second Seminole War began. (Dade County bore Major Dade’s name solely until 1997, when the Florida legislature expanded the name to Miami-Dade country.) Mr. Cotto notes that blacks and Seminoles fought as allies in this ugly conflict.

Massacre of the Whites by the Native Americans and Blacks in Florida, engraving by D.F. Blanchard for an 1836 account of the Dade Massacre at the outset of the Second Seminole War.

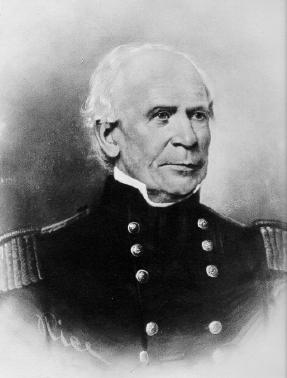

Two major American campaigns, including one led by Winfield Scott, failed. However, the Seminole were also being worn down. Like most guerillas, they couldn’t stay in one place without risking discovery and destruction.

General Thomas Jessup finally won the war through treachery. Under a flag of truce, Osceola went to an American fort, thinking he had been invited to negotiate a settlement. Instead, the Americans imprisoned him. Later Americans condemned General Jessup for this and admired their enemy Osceola instead. When Osceola died in 1838, Americans gave him a military funeral. His gravestone calls him a “patriot and warrior.” Those who tore down Lee’s statue should learn a lesson about respecting enemies.

General Thomas Jessup

General Jessup gained another success through trickery. He offered the Seminoles’ black slaves freedom under American law if they went to Arkansas. The blacks agreed. Furious Seminoles negotiating with Americans demanded that this promise be revoked. Jessup did so, breaking his word again. This makes him even more unpopular in history books, but he drove a wedge between Seminoles and black slaves. Blacks might prefer vassalage under Seminoles to slavery under whites, but what they really wanted was freedom.

Eventually, most Seminoles went West, along with “Seminole Negroes,” but the two groups had different fates. The Seminoles increasingly adopted Southern-style “chattel slavery.” Distinctions between Seminoles and Creeks began to blur, while distinctions with the “Seminole Negroes” grew sharper. Washington also treated them differently. The United States government appears to have feared blacks more than Seminoles, and approved of Indians enslaving blacks. Mr. Cotto notes that in 1848, the US Attorney General ordered that all the blacks be disarmed, but had no objection to Creeks and Seminoles owning guns.

In 1865, the United States government forced the Seminoles and other slave-owning Indians to free their blacks. The blacks, without means or education, couldn’t survive among their former masters. Many left for cities and assimilated into larger black populations.

Most Seminoles did not consider “Seminole Negros” part of the tribe. Mr. Cotto writes that in 1934, many Seminoles wanted to ban blacks entirely from tribal life. In 1976, the United States government admitted it had broken a treaty with the Seminoles and paid compensation. However, blacks weren’t included, because they were slaves and not tribe members.

In 2000, the Seminole General Council restricted tribal membership to those with at least one-eighth Seminole ancestry. Seminole “Freedmen” are still fighting in court to be included in the tribe, because of the financial benefits. Black/Indian relations can be complicated. In May, some blacks spoke against renaming Columbus Day because Indians enslaved them and whites freed them.

Mr. Cotto wrote this book to highlight complexities such as this in American history. Seminoles were once masters of huge stretches of territory and lorded over slaves. Later, whites drove most of them out of Florida, but they still had black slaves in Indian Territory. Today, tribal membership in this “oppressed” group is so profitable that the descendants of their slaves want to be treated as Seminoles.

Blacks and Seminoles were allies when the Seminoles resisted whites and blacks refused plantation slavery. Later, blacks abandoned the Seminoles because whites offered freedom and Seminoles didn’t. Today, blacks want the United States government to force Seminoles to admit them as part of the tribe.

There isn’t much white unity across nations in this story. The Spanish and the British worked with the Seminoles against white Americans. There wasn’t much red unity either. Some Creeks fought alongside white Americans against the Creeks’ Seminole cousins. From whites breaking treaties, to Seminoles raiding white settlements, to blacks burning a man alive, no group was heroic.

Mr. Cotto ends his book with admiration for the Seminole because they “show what it means to survive at any cost, against all odds.” Whites should take notice. However, Mr. Cotto is not writing to celebrate “chauvinistic triumphalism,” but to show that “narratives of one group being inherently ‘evil’ or ‘corrosive’ ” are no less absurd, and constitute a “blood libel against the ‘other.’ ” It’s a welcome counter to the “1619 Project” and white guilt.

Ensuring survival is not triumphalism. If the Seminole can celebrate their collective survival, white Americans can, too. During the Seminole wars, Americans thought white interests and national interests were the same thing. It’s the reverse today.

Read Runaway Masters to learn the complexity of racial politics, and what it takes to survive against the odds. It refutes the fairy tale about the evils of “whiteness,” but don’t expect chest-thumping about white greatness or revisionist history about white victimhood. This book doesn’t celebrate men like Andrew Jackson or the white frontiersman who started “the Republic of Florida.” They were ruthless, as were their enemies.

Nonetheless, Jackson and men like him had determination, even a kind of divine madness that drew them to conquest, danger, and adventure. Those were the kind of men who built this country. They fought Seminoles and other Indians who had the same noble spirit. One of the best things we can say about whites is that we honored those we defeated, because we recognized their bravery and dedication.

Are there such men today? No. We must become them.