David Wilmot and the Fight for the White Man

F. Roger Devlin, American Renaissance, April 3, 2020

If any event in American history can be singled out as the beginning of a path with led almost inevitably to sectional controversy and civil war, it was the introduction of the Wilmot Proviso. The proposal of Pennsylvania’s Democratic Congressman David Wilmot, that slavery be excluded from any territory the nation acquired from Mexico, threw the issue of slavery into the center of the political arena.

– Eric Foner

For the better part of a century, the question of slavery — whether to abolish it, preserve it, or extend it — was at the center of American politics. This was the unhappy legacy of trying to build a multi-racial nation. Although much has changed since the 18th and 19th centuries, multi-racialism continues to be the great American dilemma. The difference is that today, no major figure defends the interests of whites. David Wilmot (1814–1868), who gave his name to the famous proviso of 1847, did just that. Whatever turns the politics of his day might take, he never wavered in his devotion to the founding stock of his nation.

Wilmot was a young freshman Congressman when he put before his colleagues the “proviso” that has immortalized him, but it was only the most celebrated moment in a long career dedicated as much to promoting the interests of free (that is, mainly white) labor as it was to opposing the extension of black slavery.

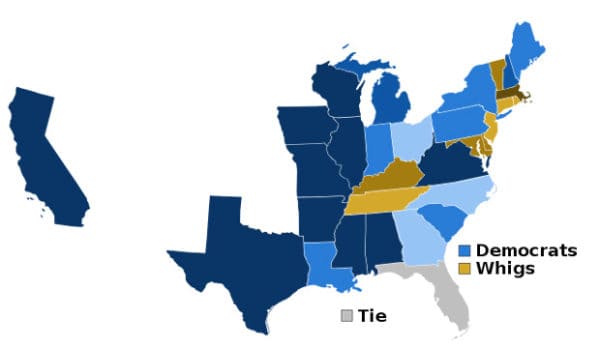

Wilmot was trained in the law and became active in the local politics of northern Pennsylvania in his twenties, almost as soon as he began to practice law. At this time, national elections were divided between the Democrat Party, which had formed around the charismatic figure of Andrew Jackson, and the smaller Whig Party, which Henry Clay had cobbled together from factions opposed to Jackson. The Democrats were the party of the common man, championing the popular will, while the Whigs emphasized the rule of law and protections for commerce and industry. These parties were for the most part not sectional; they had supporters in both North and South. Historians call this the Second Party System, which replaced the split between Federalists and anti-Federalists. David Wilmot joined the Democrats.

America’s Second Party System: 1828–1854.

Americans of the Jackson Era were beginning to realize the potentially explosive nature of the slavery issue. The abolitionist movement went into high gear in the 1830s, and its sympathizers began bombarding Congress with petitions to end or limit slavery. In response, a congressman from South Carolina proposed a so-called gag rule to table automatically any motions on the South’s peculiar institution — meaning that they could not be debated. Opponents, including former president John Quincy Adams, held that such a rule violated the First Amendment’s guarantee of the “right to petition the government for redress of grievances.” Enough Northern Congressmen still hoped to avoid a fight over slavery, however, that the gag rule was adopted in May 1836. During 1837–1838 alone, no fewer than 130,000 anti-slavery petitions were submitted to Congress — and ignored.

The gag rule was rescinded in December 1844 — just after the young Wilmot was elected to Congress. On one of his first days in the House, an Alabama colleague proposed restoring it. Significantly, Wilmot voted in favor of the gag rule — which did not pass — allying himself with many Southerners who later became his fiercest opponents. He also supported the admission of Texas as a slave state, and even voted against a proviso to exclude slavery from that state. David Wilmot was no radical abolitionist.

Because the proviso for which he became famous would have stopped the extension of slavery to the American Southwest, some have accused Wilmot of inconsistency. His biographer explains:

Where slavery existed in Wilmot’s time, it was a legalized institution written into the constitution and the laws of the States or the territorial governments — even recognized and protected in the Constitution. The several States, and Texas as a formerly independent republic, were sovereign powers with absolute authority to determine their internal affairs and policies. Much as he deplored and condemned slavery, he could not countenance the proposition that Congress should invade these sovereignties for the abatement of this, or any other, evil. When, however, the schemes of the slavery advocates extended to previously undeclared projects for adding huge territories toward the southwest — territories on which slavery had never been legally fastened — territories as yet unorganized into sovereign States and, therefore, still subject to control by Congress — neither legal nor States’ right inhibitions prevented his free expression [of opposition].

Most of Wilmot’s first term in Congress was devoted to other matters: He served on the select committee that established the Smithsonian Institution, urged repeal of the 1842 tariff, and supported President Polk’s handling of the Mexican-American War. His great moment came as the 29th Congress was approaching adjournment, scheduled for noon, August 10, 1846. Just two days before, as the chamber was scrambling to conclude unfinished business, the Speaker sent a message from Polk requesting an appropriation of $2 million “for the purposes of defraying any extraordinary expenses which may be incurred in the intercourse between the United States and foreign nations.” This money was to help negotiate possible territorial concessions from Mexico at the conclusion of the Mexican-American War. A New York Congressman put it bluntly: “It looked very much as if the money was wanted to purchase California, and a large part of Mexico to boot.”

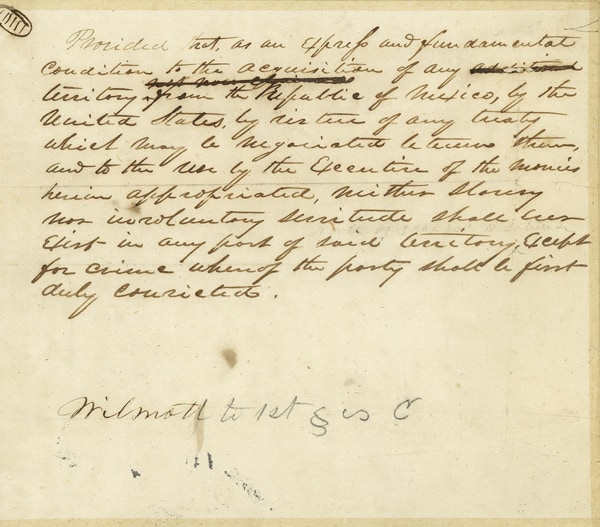

The House held a two-hour debate on the proposed appropriations. The first speaker, Hugh White of New York, suggested an amendment to prohibit the extension of slavery into any territory that might be acquired from Mexico, but failed to offer the wording for one. Wilmot, fifth to speak, proposed his famous proviso:

Provided, That as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any territory from the Republic of Mexico by the United States, by virtue of any treaty which may be negotiated between them, and to the use by the Executive of the moneys herein appropriated, neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory, except for crime, whereof the party shall first be duly convicted.

Wilmot Proviso, August 8, 1846. Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, National Archives.

If the language sounds familiar, it is because the Thirteenth Amendment, which freed the slaves, was modeled on Wilmot’s Proviso.

The bill, including the Proviso, was adopted by the House by a vote of 83–64. Two days later — and just one hour before adjournment — the matter was taken up by the Senate, which failed to vote before the clock ran out. Most observers doubt the Proviso would have passed in the Senate, but Wilmot himself thought it had a chance. In any case, the proviso never again came so close to passage; by the time Congress next convened, opponents had had time to organize against it.

David Wilmot returned to his district to run for re-election. The proviso played no role in the campaign — most voters were thinking about the tariff — but Wilmot would have another chance with his proviso just six months later.

Congressional restrictions on slavery before Wilmot

To understand why the proviso was so important — and why it invoked intense passion when it was reintroduced — it is necessary to look at how the United States had handled the question of slavery and its expansion for the preceding 62 years. The first Congressional attempt to limit the spread of slavery dates back to 1784, and Thomas Jefferson’s proposed Land Ordinance on the Northwest Territories. The Northwest Territories were a politically unorganized area between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. Jefferson’s Ordinance would have divided the territories into states. Those states would be candidates for admission to the Union on the same terms as the 13 existing states, except that Jefferson’s draft also included the following passage:

Resolved, That after the year eighteen hundred of the Christian Era, there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in any of said states, otherwise than in punishment of crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted to have been personally guilty.

Six of the states supported the ordinance with this anti-slavery provision, but the provision needed seven for adoption. If New Jersey’s representative had not been out sick that day, slavery might have been limited to the Eastern Seaboard. Three years later, the Northwest Ordinance was passed, but with a slavery ban limited to the area north of the Ohio River.

Wilmot was aware of this precedent, and later said on the floor of the House that Jefferson’s original proposal:

looks very much like the ‘Proviso.’ Here is the original ‘firebrand’ — the heresy, for holding onto which men are now proscribed by the government of their country. Mr. Jefferson, had he lived at this day, would have been denounced as an abolitionist, and a disturber of the peace of the Union.

For many fire-eating Southerners who insisted on spreading slavery to every newly acquitted territory, it was no doubt embarrassing that so eminent a Virginian as Jefferson had taken a position that would have, as Wilmot noted, made him a pariah in the South 60 years later.

In 1820, with the famous “Missouri Compromise,” Congress once again tried to restrict slavery in the territories. At issue this time was the Louisiana Purchase where, unlike in the former Northwest Territory, slavery had already been established under Spanish and French rule, and persisted under treaty obligations assumed by the United States at the time of purchase. When Missouri petitioned for statehood, Congressman James Tallmadge of New York proposed making its admission conditional on abolition. The Tallmadge Amendment passed in the House but failed in the Senate. Neither body would yield, and the proposal died when the 15th Congress adjourned.

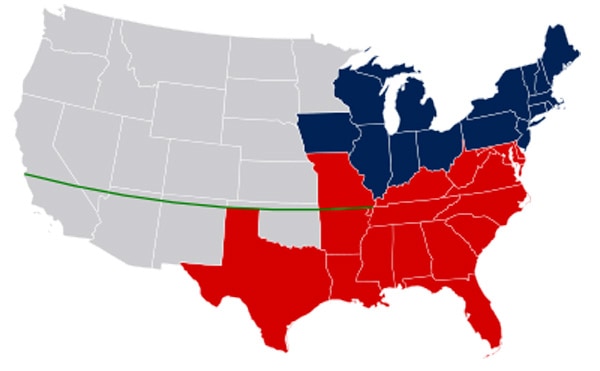

By the time the 16th Congress met in 1820, Maine was also petitioning for statehood. The compromise Congress eventually reached provided that 1) admission of Maine to the Union would be conditional on admitting Missouri without restriction on slavery; and 2) slavery would henceforth be forbidden to the West of Missouri and north of 36° 30’ north latitude.

Missouri Compromise line.

During the ensuing years, North and South became so jealous of power in Congress that new states were admitted to the Union in pairs, one slave and one free. Florida and Iowa were such a pair; so were Arkansas and Michigan.

Historical significance of Wilmot’s Proviso

Wilmot’s Proviso would have had little effect on existing slaves since there were extremely few blacks in the territories to which it would have applied. Its significance was twofold: 1) It broke with the Missouri Compromise that had worked for the previous 27 years because it would have outlawed slavery in newly acquired territory south of 36° 30’; and 2) It became the flashpoint for a political realignment that added an ideological split to the existing Democrat/Whig division. This split was broadly regional.

Territory affected by the Wilmot Proviso in red.

The South wanted not only to preserve slavery but to extend it westward, because it feared the long-term survival of the “peculiar institution” required extension into new territory. The Northeast was strongly anti-slavery and pro-abolition. The balance of power was held by a faction strongest in the Northwest that disapproved of slavery but was content to keep it from spreading. These men, like their Southern colleagues, believed that limiting the expansion of slavery would eventually doom it where it already existed. David Wilmot belonged to this moderate faction.

In December 1846, the 29th Congress reconvened for its final session. Another Mexican-War-related appropriations bill — which included the Wilmot Proviso — came up in February 1847. In the stormy debate that followed, the appropriation itself was largely overshadowed by the Proviso. When Southern Congressmen who had formerly considered Wilmot an ally now accused him of being an abolitionist, he replied:

What do we ask? That free territory shall remain free. We demand the neutrality of this government upon the question of slavery. Is there any complexion of Abolitionism in this, sir? I have stood up at home, and battled, time and again, against the Abolitionists of the North. I stand by the Constitution . . . . I adhere to its letter and spirit. I would not invade one single right of the South. But, sir, the issue now presented is not whether slavery shall exist unmolested where it now is, but whether it shall be carried to new and distant regions where the footprint of a slave cannot be found. This, sir, is the issue. On it I take my stand, and from it I cannot be frightened or driven by idle charges of abolitionism. I ask not that slavery be abolished. I demand that this Government preserve the integrity of free territory against the aggressions of slavery — against its wrongful usurpations.

Behind these clear declarations, however, hovered the unanswered question of whether slavery could ultimately survive in the South if its congressional delegation became a dwindling minority.

Also at stake were the working conditions of free white men. Slavery served much the same purpose in antebellum America that mass third-world immigration does today: It drove down wages. If the new territories were opened to slavery, it would depress the wages of white workers. Wilmot emphasized this in the same speech:

Shall these fair provinces [California and New Mexico] be the inheritance and homes of the white labor of free men or the black labor of slaves? Shall the South be permitted, by subduing free territory and planting slavery upon it, to wrest these provinces from Northern freemen, and turn them to the accomplishment of their own sectional purposes and schemes?

In his correspondence, Wilmot was emphatic about his motives: “I am helping to fight the battle for the rights of the white men [emphasis in the original] of this country . . . . I would preserve to free white labor a fair country, a rich inheritance, where the sons of toil, of my own race and own color, can live.” He added: “It is not true that the defenders of the rights of free labor seek the elevation of the black race to an equality with the white.”

The Proviso debate and the Free-Soil Movement

Debate continued for a week. There were nearly 30 speeches, about equally divided between the friends and enemies of the Proviso. On February 15, the House passed the bill, including the Proviso, by a vote of 115–105. This vote crossed party lines: 61 Democrats and 48 Whigs voted for the Proviso and against extending slavery; 24 Whigs, 18 Democrats from the free states, and 63 votes from the solid South voted against the Proviso.

The same debate occupied the Senate for much of February, and on March 1, the Proviso was defeated, 21 to 31. The appropriation itself was passed.

That spring, the Proviso controversy filled the editorial pages and news columns, came up in stump speeches, and was debated on street corners across the country. The legislatures of all slave states passed resolutions condemning the Proviso; those of all but two of the free states supported it. For the remainder of 1847 and into the following year, agitation increased. Wilmot Proviso leagues sprung up throughout the free States, and there were mass meetings and conventions of opposition throughout the South.

As the 1848 presidential election approached, the Democrat Party in the North faced a dilemma: It could either maintain its alliance with Southern, pro-slavery Democrats (and keep its overall national majority) by rejecting the Proviso, or gratify the majority of its own constituents by championing the Proviso but risk splitting the Party along regional lines and doom its chances in the general election. Most of the party’s men were unwilling to sacrifice their ambitions by splitting the party, whatever their feelings about slavery or the Proviso. In New York, the largest of the states, this faction gained control of the State Convention and replaced uncooperative, pro-Proviso members of the State central committee even though their terms had not expired.

Outraged pro-Proviso Democrats held a convention of their own, and David Wilmot came up from Pennsylvania to address it. He argued that cotton, tobacco, and rice were the only crops suitable for slave cultivation, that they exhausted the soil in 15-20 years, and that planters were therefore continually looking for new land. The South’s desire to increase slave territory therefore amounted to an effort to postpone the inevitable. This argument, that slavery was ultimately doomed because of soil exhaustion, is still heard today. If correct, it suggests slavery would have ended even without the Civil War.

David Wilmot’s house in Bethany, Pennsylvania.

At the Democratic National Convention in May 1848, an anti-Proviso candidate, Sen. Lewis Cass of Michigan, was nominated for the presidency. The following month, the Whig Party, also much divided over the Proviso, nominated Gen. Zachary Taylor, a hero of the Mexican War but, as a Southerner, no friend of the Proviso. The sizable pro-Proviso wings of both parties were thus left without a candidate. In response, they met together in August to start the Free-Soil Party, which nominated former president Martin Van Buren to run against Cass and Taylor. David Wilmot took as prominent a role in the new Party’s activities as his legislative duties in Washington would allow, and was its favored candidate for speaker of the House. He is said to have made 25 speeches on Van Buren’s behalf. In the election, Van Buren won 10 percent of the national vote, splitting the Democrats and handing the presidency to Zachary Taylor and the Whigs.

Over the course of the next two years, enthusiasm for the Proviso waned among the political class of the North, yielding to the imperative of preserving the Union even if it meant less strident opposition to slavery. The result was the ramshackle Compromise of 1850 that admitted California as a free state, let New Mexico decide for itself, and included the Fugitive Slave Act, which made it easier to catch runaway slaves. Wilmot felt no enthusiasm for this muddle.

When California overwhelmingly approved a state constitution prohibiting slavery, it showed the intensity of sectional feeling. Southern representatives, who had previously claimed the right of states to regulate slavery for themselves, poured the harshest invective on California’s voters, calling their decision worse than the Proviso. They made the curious claim that California had violated the Missouri Compromise, although that agreement had only prohibited slavery north of 36° 30’. It did not require slavery south of that line.

Wilmot’s later career as a Republican

David Wilmot’s Pennsylvania rivals, led by future President James Buchanan, sabotaged his reelection in 1850; his defeat was another symptom of the changed mood among Northern politicians. But Wilmot’s Proviso and the Free Soil cause continued to be popular among the ordinary people of the North, and this led to the founding of the Republican Party in 1854. American historians speak of a transition from the Second Party System of Whigs and Democrats to a far more sectional Third Party System (third in sequence, not three parties) in which the North largely voted Republican and the South Democratic.

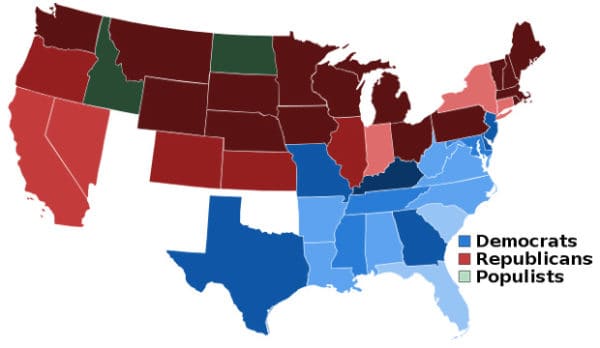

America’s Third Party System: 1856–1894.

Wilmot was not out of office long before he was elected president judge of the Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas (1851–1861). He assumed a leading role in founding the Republican Party of Pennsylvania, and at the Republican National Convention of 1856, which nominated John C. Frémont for president (“Free Men, Free Soil, Frémont!” ran the slogan).

At the opening session of the 1860 Republican Convention, Wilmot was elected temporary chairman and gave the keynote address. He also organized support for Lincoln among the Pennsylvania delegation, a service that was crucial for Lincoln’s nomination. Pres. Lincoln later offered him a place in his cabinet, but Wilmot declined in favor of filling the two-year Senate vacancy created by Simon Cameron’s appointment as Secretary of War. Wilmot finished his days as a federal judge, nominated by Lincoln and confirmed by the Senate in March 1863.

David Wilmot’s opposition to slavery as harmful to the interests of white labor does not endear him to contemporary historians, whose tastes run more to John Brown-style abolitionism. But our nation is gradually coming to realize that its systematic disregard of working whites is driving countless of these patriotic Americans to unemployment, hopelessness, addiction, and even suicide. What these forgotten European-Americans need is a new David Wilmot.