The War With Mexico

Erik Peterson, American Renaissance, September 1995

April 25, 1996 will mark the 150th anniversary of the outbreak of the Mexican War. Today, most Americans have been taught that it was an imperialistic war of aggression, and Mexicans cite the “illegal seizure” of their territories to justify the current colonization of the American Southwest. In fact, by contemporary and even by today’s standards, the war was far from unjustified.

The conflict began with Texas. When the colony of New Spain broke free from its European namesake in 1821 and christened itself Mexico, it inherited vast lands north of the Rio Grande that had been only nominally under Spanish control. Texas was a remote wilderness, constantly terrorized by Comanches, with a Mexican population of only 3,500.

Mexico could have concentrated on subduing the Indians and settling its northern territories. Instead, almost from the first days of independence, the country was wracked by a series of political upheavals. The small, predominantly white, Spanish-speaking elite consumed all of its energies in fratricidal power struggles, while the Mestizo and Indian majority remained mired in poverty.

In order to legitimize its claim on Texas, Mexico needed to occupy it. Since it was unable to do this itself, the Mexican government enlisted the help of immigration agents or empresarios to recruit settlers from the United States. The empresarios, chief among them Steven F. Austin, acted as representatives of the Mexican government. They were authorized to offer immigrants cheap land in return for accepting Mexican citizenship and converting to Roman Catholicism. The Americans appear to have made a good faith effort to fulfill the first requirement but often sidestepped the second.

The new settlers created a frontier version of the plantation-based, slave-owning society of the neighboring Southern states. By the early 1830s, however, Mexico began to fear that the empresarios had been too successful: American immigrants outnumbered Mexicans four to one, and seemed likely to identify with the land of their birth.

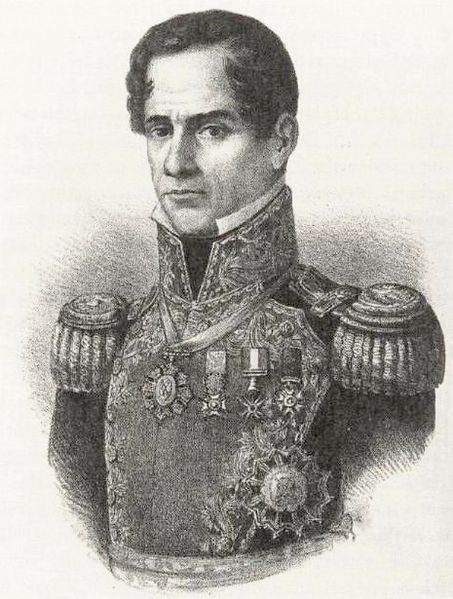

General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna became President of Mexico in 1833, and in 1835 abrogated the constitution and declared himself dictator. This act alone provoked rebellion in seven Mexican states, including Texas, but Texans had additional reasons for discontent. Determined to reverse the Americanization of the territory, Santa Anna had decreed an end to American immigration, abolished slavery, repealed the local political autonomy Texans had enjoyed, and announced he would forcibly settle the land with Mexican convicts.

Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna

It is hard to imagine policies better calculated to rouse the ire of free-spirited Texans. In 1836 they overthrew local Mexican garrisons and declared independence. Santa Anna promptly invaded Texas with an army of 3,000 men, but after several engagements was decisively beaten by Sam Houston’s men at the battle of San Jacinto. Santa Anna was captured, and in order to gain freedom agreed to recognize Texan independence, with the Rio Grande as its border. He later disavowed this treaty, and Mexico waged a nine-year guerrilla war against its former territory.

The United States recognized Texas as an independent republic in 1837, and recognition soon followed from France, Great Britain, Holland, and Belgium. Despite strong Texan sentiment to join the Union, the American government demurred; Mexico threatened war if Texas were annexed, and the United States was unwilling to upset the delicate balance between slave and free states.

Western Destiny

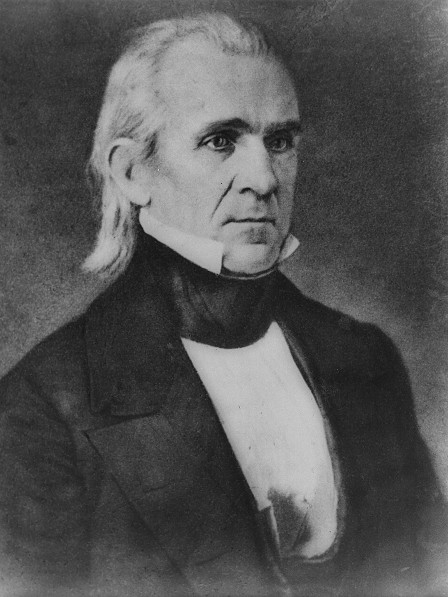

The presidential election of 1844 brought into office a firm believer in what soon became known as “manifest destiny.” James K. Polk was determined to complete the annexation of Texas, buy California from the Mexicans, and bluff the British into ceding the better part of Oregon. The Texans were impatient for a settlement, and Polk’s predecessor, John Tyler, had welcomed the Lone Star State into the Union three days before he left office. If the United States had continued to hesitate because of Mexican sentiments, Texas might have remained independent or even accepted protectorate status from Britain or France.

President James K. Polk

As for California, Mexico’s position was so weak it was bound to be supplanted soon, if not by the U.S. then by Britain, Russia, or perhaps even the Mormons. Polk had reason to believe that Mexico would be willing to sell. In the meantime, if Oregon joined the Union the careful balance of free and slave states could be maintained.

When Texas joined the United States in March 1845, Mexico immediately broke off diplomatic relations and threatened war. Polk sent General Zachary Taylor with 2,000 men to protect the new state from Mexican depredation while annexation was accomplished. Nevertheless, Polk had every reason to seek a diplomatic solution with Mexico, partly because he was afraid war might break out with Britain over the Oregon question. He decided to send a special emissary, John Slidell, to Mexico with instructions to resolve all outstanding issues.

On the question that had caused the rupture–annexation of Texas–Slidell was not to compromise. Mexico had been unable to reconquer her wayward territory, whose independence had been recognized by the major powers. By refusing to accept the loss of Texas and by persisting in border skirmishes, Mexico had perpetuated a crisis on the American border that could have led to European intervention. Texas was now part of the United States.

Several other matters were open to negotiation. One was the settlement of $3.25 million in claims by Americans on the Mexican government. Mexico had recognized these claims under international arbitration, but had later refused to pay. Another issue was final determination of the Texas-Mexico border. As a Mexican territory, the Texas border had been at the Nueces River, but after their revolution the Texans claimed the Rio Grande as the border–without, however, establishing full authority in the disputed territory. Slidell was authorized to release Mexico from the $3.25 million obligation in return for recognition of the Rio Grande border. This was a reasonable offer, especially since Mexico had already, in effect, declared war, and unpaid international obligations were then considered grounds for belligerency. By accepting this offer, Mexico could easily have avoided war.

Besides these immediate questions, Slidell was to offer $15 million but, if necessary, propose considerably more for the Mexican lands stretching from Texas to the Pacific. If the entire tract was not for sale, he was to offer $5 million for New Mexico.

The Mexican government, threatened by a militant opposition and wracked by internal dissension, refused even to receive Slidell. This was a fatal mistake. The rebuff left Polk with no means to negotiate a peaceful settlement. He ordered Zachary Taylor into the disputed region between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande, but he warned Taylor not to seek engagement with any Mexican troops he might encounter. In the meantime, he made preparations to ask Congress to declare war, but Mexico forced the issue.

On April 23, 1846, sixteen hundred Mexican troops crossed the Rio Grande. Two days later they ambushed a U.S. Army patrol, inflicting sixteen casualties and taking prisoners. Mexico “shed American blood upon American soil,” and the war began.

The Mexicans, of course, saw the war as a just effort to retake what was rightfully theirs. Why, though, would they make war on the United States when they had been unable to subdue a breakaway territory? Astonishingly enough, Mexico fully expected to win. It had a standing army of 27,000 men versus an American army of only 7,200. French advisors to the Mexican army had an exaggerated estimate of its fighting prowess, which the Mexicans gladly believed. The generals intended not only to take back Texas but to annex parts of the United States. Indeed, the Mexican dictator of the moment, General Mariano Paredes, boasted that he would not negotiate Until the Mexican flag flew over the capitol dome in Washington. The Mexicans were also counting on diplomatic and even military support from Britain, but the Oregon issue was resolved just before they attacked.

In his two-volume work, The War With Mexico, Pulitzer prize-winning historian Justin H. Smith described the war fever among the generals: “Mexico wanted [war]; Mexico threatened it, Mexico issued orders to wage it.” By no stretch of the imagination was Mexico thrust into an unwanted war by Yankee aggressors.

American Arms

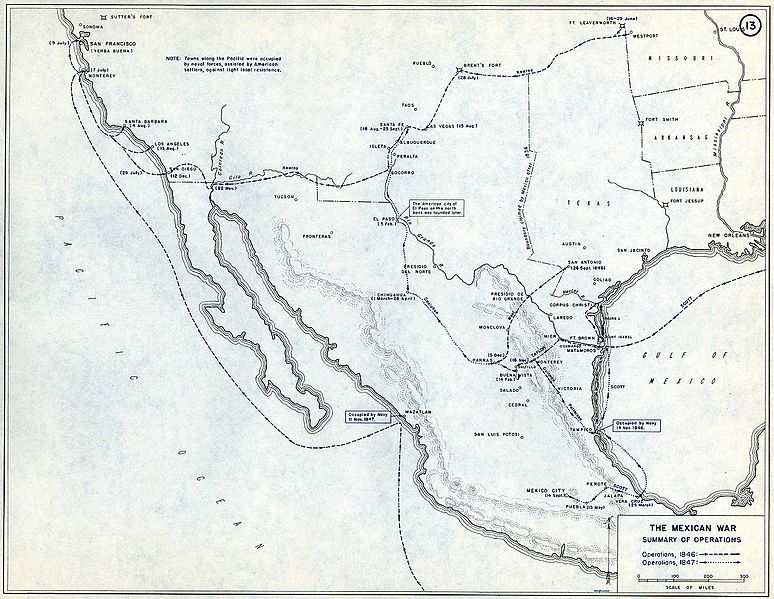

The military history of the Mexican War makes interesting reading and is a credit to the tradition of American arms.

Throughout the two-year campaign, small but superbly led and highly motivated American units consistently outfought the Mexicans. The Mexican army, impressive enough in numbers and parade-ground panache, was utterly unable to fight a determined adversary.

The American war effort was not all glorious. Although the Regular Army behaved with proper discipline, some of the volunteer militia units conducted themselves so badly they created guerrilla resistance among previously noncombatant Mexican civilians. Also, the war was all-too-effective training for America’s fratricidal tragedy just 13 years later. Among the junior officers sent to Mexico, 200 would go on to be generals in the Union and Confederate armies.

The Treaty of Guadaloupe Hidalgo ended the war in 1848 on terms advantageous to the United States. Mexico agreed to cede California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and the western parts of Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico — in all, 525,000 square miles of land that contained virtually no Mexicans.

All but overlooked today is the fact that the United States forgave the $3.25 million debt, and paid Mexico $15 million for the ceded territories. According to the rules of 19th century warfare, after routing Mexico’s armies and occupying its capital, the United States could have seized territory under whatever terms it liked. To have paid what it considered a reasonable amount before fighting an expensive war — estimated to have cost $100 million — was a magnanimous gesture.

The Mexican position today is that the United States stole Mexican territory. However, Mexico could have refused the money or promptly returned it. By accepting payment it ratified the transfer. Furthermore, only five years later, Mexico agreed to sell an additional parcel of land to the United States, which was to be used for the southern route of the transcontinental railway. The Gadsden Treaty of 1853 settled a number of disputes about the post-1848 U.S.-Mexico border and secured 19 million additional acres of territory for the United States. In return, the United States paid Mexico $10 million. There was no threat of war or coercion. This freely negotiated settlement of the new border and additional transfer of land were further ratification by Mexico of the consequences of war with the United States.

In conclusion, the United States had ample to reason to pursue, in 1846, the course that it did. As a practical matter, the real issue decided by the war was whether Britain, France, Russia, Mexico or the United States would acquire the vast territories of the American Southwest. President Polk resolved the question in favor of the United States in a refreshingly straightforward nineteenth century manner.

[Editor’s Note: This essay is in A Race Against Time: Racial Heresies for the 21st Century, a collection of some of the finest essays and reviews published by American Renaissance. It is available for purchase here.]