Why Are Human Groups So Different?

Grégoire Canlorbe, American Renaissance, March 20, 2020

This is part two of a two-part interview. See here for part one.

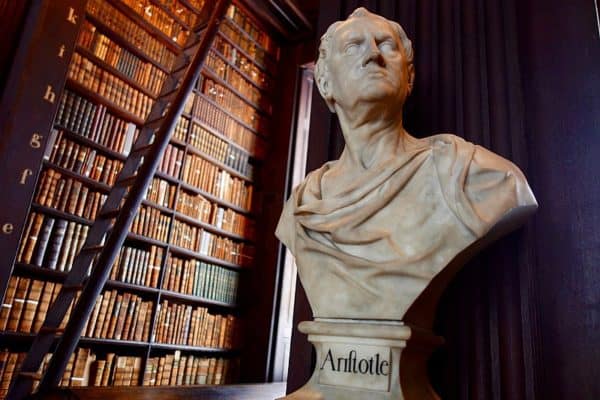

Grégoire Canlorbe: A rudimentary cartographer of intelligence, medieval philosopher Maimonides referred to “the extreme Turks who wander about in the North, the black-colored people who live in the South, and those in our country [plausibly Egypt] who look like them,” not only as people who “have no religion, neither one based on speculation nor one received by tradition,” but as “irrational beings.” How do you sum up the progress achieved since the time of A Guide for the Perplexed in mapping race differences in intelligence?

Peter Frost: It’s like mapping a moving object. We’re always evolving, and there is evidence that mean intelligence has changed during recorded history, particularly in Europe.

In the time of Maimonides, mean intelligence seems to have been highest within a middle zone stretching from the Mediterranean, through the Middle East and into South Asia and East Asia. By the end of the first millennium, that zone had reached the limits of its mode of production. Northwest Europe, where kinship was weaker and individualism stronger, was more conducive to the creation of a true market economy, which would favor not only cognitive ability but also future time orientation, reluctance to settle personal disputes with violence, and ability to process numerical and textual information — in short, a middle-class mindset.

Gregory Clark has used demographic data to chart the growth of the English middle class. He found that it grew steadily from the 12th century onward, its descendants not only growing in number but also replacing the lower classes through downward mobility. By the 1800s, its lineages accounted for most of the English population. Meanwhile, England became more and more middle class in culture.

With respect to Northwest Europeans in general, Georg W. Oesterdiekhoff has argued that mean intelligence steadily rose during late medieval and early modern times. Previously, most people were stuck at the stage of preoperational thinking. They could learn language and behavioral norms but their ability to reason was hindered by cognitive egocentrism, anthropomorphism, finalism, and animism. From the 16th century onward, more and more people could understand probability, cause and effect, and another person’s perspective, whether real or hypothetical. As this “smart fraction” grew, it eventually reached a point where intellectuals were not loners anymore. They were communities of people who could exchange ideas in clubs, salons, coffeehouses, and debating societies. Thus began the Enlightenment.

During the same time period, mean cranial capacity seems to have increased. An increase has been demonstrated from at least 1800 in Germans and 1820 in white Americans (the specimens don’t go back earlier), and it cannot be easily explained by changes to nutrition or childhood disease. Infant mortality is a good proxy for both, and it began to decrease only around 1900.

What goes up can come down. In the late 19th century, cottage industries began to give way to industrial capitalism. Businessmen no longer translated financial success into early marriage and large families who could help with the work. If they needed more workers, they simply hired them. Large families thus became a net cost for businessmen at a time when the costs of maintaining a high-status lifestyle were rising. For all these reasons, middle-class fertility entered a long decline, interrupted only by the baby boom of the mid-20th century.

The result was a decline in mean intelligence. The evidence is incomplete but consistent:

– Mean reaction time has risen in the United Kingdom by 13 points since the Victorian era. A Swedish study has found the same change, particularly in cohorts born since the 1970s. People are taking a longer time to process the same information.

– In Iceland, since the cohort born in 1910, there has been a steady decrease in the mean frequency of alleles associated with educational attainment.

– The Flynn effect is ending throughout the West. In fact, it is reversing in Scandinavia, England, and Austria.

Please note: The Flynn effect never was a real increase in intelligence. Do you think people are smarter today than a century ago? Read the popular literature from back then. Examine the vocabulary and the complexity of the plots. Also examine what people were expected to know upon graduation from elementary school. Yes, IQ scores rose during the 20th century, but the reason is largely because people became more familiar with test-taking and with thinking in terms of standardized answers to standardized questions. Real intelligence was actually declining all that while, and the decline is becoming apparent on IQ tests with the end of the Flynn effect.

The decline in intelligence is no longer due to the slump in middle-class fertility. For one thing, use of contraception and abortion has spread to families of all social classes. For another, a Norwegian study has shown that the reversal of the Flynn effect in Norway is largely explained by “within-family variation.” In other words, the current decline is not due to the lower class outbreeding the middle class or to immigrants outbreeding natives. It’s due to younger siblings being dumber than older siblings.

That explanation does not exclude a genetic cause. In Norway, siblings are increasingly half-siblings. The above finding was based on a comparison of brothers in the military conscript register (only men are conscripted in Norway), and for a woman to produce a pair of brothers, she has to have three children on average. Among Norwegian women with three children, 36.2 percent have had them by two or more men. In Norway, multi-partner fatherhood is most common among men with the lowest level of education, and multi-partner fertility has been increasing among such men. Subsequent fathers of siblings thus tend to be less intelligent. Furthermore, within a family, half-siblings contribute more to change in mean sibling IQ over time because they tend to be born farther apart than full-siblings, i.e., the mother loses some time while searching for a new partner.

The current IQ decline in Norway is probably due to the decomposition of the family, and to fathers who are little more than sperm donors. The children acquire the mother’s family name and later, if she remarries, her new husband may adopt them. Official statistics are thus misleading. In reality, more and more individuals are not fathered by their legal “fathers.” This is a long-term trend throughout the West. The family has ceased to be a legally enshrined “pact to procreate” and is becoming a group of two or more individuals who share space for a certain time.

Interview continues below…

References

Bratsberg, B., and O. Rogeberg. (2018). Flynn effect and its reversal are both environmentally caused. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 115(26): 6674-6678.

Clark, G. (2007). A Farewell to Alms. A Brief Economic History of the World. Princeton University Press: Princeton and Oxford.

Clark, G. (2009). The domestication of man: The social implications of Darwin. ArtefaCTos 2: 64-80.

Flynn, J.R. (2007). What is Intelligence? Beyond the Flynn Effect. Cambridge University Press.

Frost, P.F. (2018). Rise of the West, part II. Evo and Proud, December 27.

Jantz, R.L., and L.M. Jantz. (2016). The Remarkable Change in Euro-American Cranial Shape and Size. Human Biology 88(1): 56-64.

Jellinghaus, K., H. Katharina, C. Hachmann, A. Prescher, M. Bohnert, and R. Jantz. (2018). Cranial secular change from the nineteenth to the twentieth century in modern German individuals compared to modern Euro-American individuals. International Journal of Legal Medicine 132: 1477-1484.

Kong, A., M.L. Frigge, G. Thorleifsson, H. Stefansson, A.I. Young, F. Zink, G.A. Jonsdottir, A. Okbay, P. Sulem, G. Masson, D.F. Gudbjartsson, A. Helgason, G. Bjornsdottir, U. Thorsteinsdottir, and K. Stefansson. (2017). Selection against variants in the genome associated with educational attainment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 114(5): E727-E732.

Madison, G. (2014). Increasing simple reaction times demonstrate decreasing genetic intelligence in Scotland and Sweden, London Conference on Intelligence, Psychological Comments, April 25 #LCI14 Conference proceedings.

Madison, G., M.A. Woodley of Menie, and J. Sänger. (2016). Secular Slowing of Auditory Simple Reaction Time in Sweden (1959-1985). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, August 18.

Oesterdiekhoff, G.W. (2012). Was pre-modern man a child? The quintessence of the psychometric and developmental approaches. Intelligence 40: 470-478.

Rindermann, H. (2018). Cognitive Capitalism. Human Capital and the Wellbeing of Nations, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press.

Teasdale, T.W., and D.R. Owen. (2005). A long-term rise and recent decline in intelligence test performance: The Flynn Effect in reverse. Personality and Individual Differences 39(4): 837-843.

Woodley, M.A., J. Nijenhuis, and R. Murphy. (2013). Were the Victorians cleverer than us? The decline in general intelligence estimated from a meta-analysis of the slowing of simple reaction time. Intelligence 41: 843-850.

Grégoire Canlorbe: The first (to my knowledge) to notice a link between Western Christianity and Northwest Europeans’ domestic individualism was anthropologist Jack Goody. In his 1983 book The Development of the Family and Marriage in Europe, he wrote that the Church secured its land interests by promoting the nuclear and equalitarian family. You proposed a reverse cause and effect, namely that the Catholic Church was actually assimilating (instead of shaping) the domestic norms of Europeans. Could you tell us more about your reading?

Peter Frost: North and west of a line running from Trieste to St. Petersburg a different social environment has prevailed for at least a millennium: Almost everyone is single for at least part of adulthood, and many stay single their entire lives; in addition, households often have non-kin members, and children normally leave the nuclear family to form new households. This weak-kinship environment is associated with an unusual pattern of behavior: Northwest Europeans are more individualistic, less loyal to kin, and more trusting of strangers.

In a recent study, Jonathan Schulz and others have ascribed this behavior pattern to Western Christianity, particularly its ban on consanguineous marriages and a consequent weakening of family ties and strengthening of impersonal relationships. Therefore, the ban must have predated the behavior pattern. Actually, no one knows which came first. As we go farther back in time, we have less data to work with, but the same pattern still appears in the little we do have. In 13th-century Lincolnshire, households were already nuclear and a late age of first marriage was the norm: 24 for the woman and 32 for the man. In 9th-century France, households were small and nuclear among married people, 12 to 16 percent of adults were unmarried, and both sexes were marrying in their mid to late twenties. Earlier data are too fragmentary to produce firm conclusions. Furthermore, the data usually focus on elite males who typically had young brides. Nonetheless, we see evidence of first marriages at late ages, such as observations by Julius Caesar and Tacitus that the people of the Germanic tribes married late.

The direction of causality may thus run in the other direction. The Northwest European behavior pattern does not exist because Western Christianity diverged from Eastern Christianity on the question of consanguineous marriage. Rather, the divergence happened because Western Christianity was assimilating the behavioral norms of its converts.

Let’s look more closely at the ban on consanguineous marriages, particularly its timeline. Roman Civil Law had banned them only for first cousins. The first legal code to go farther was the mid-7th century Visigothic Code, which went two degrees farther. Then, in the early 9th century, the Church changed its way of calculating degrees of kinship by adopting the Germanic system. Under the Roman system, first cousins were considered fourth degree. The Germanic system made them second degree, thereby doubling the number of forbidden marriage partners. Thus, although the ban was Church-enforced, it seems to have originated among the converted Germanic peoples.

The same may apply to other beliefs and practices. Why, for instance, is the doctrine of original sin and hereditary guilt more developed in Western Christianity? One reason may be that the converted peoples regulated their behavior much more by internal means — by feeling guilt over wrongdoing, instead of being shamed by others. In the guilt cultures of Northwest Europe, the average person felt guilty even about transgressions that no one else had witnessed. The burden of guilt had to be regularly purged somehow, and Western Christianity became oriented to that end.

Interview continues below…

References

Frost, P. (2017). The Hajnal line and gene-culture coevolution in northwest Europe. Advances in Anthropology 7: 154-174.

Frost, P. (2019). Was Western Christianity a cause or an effect? Comment on: J.F. Schulz, D. Bahrami-Rad, J.P. Beauchamp, and J. Henrich. The Church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation. Science 366 (6466)

hbd chick (2014). Big summary post on the Hajnal Line. October 3

Schulz, J.F., D. Bahrami-Rad, J.P. Beauchamp, and J. Henrich. (2019). The Church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation. Science 366(707): 1-12.

Seccombe, W. (1992). A Millennium of Family Change. Feudalism to Capitalism in Northwestern Europe. London: Verso.

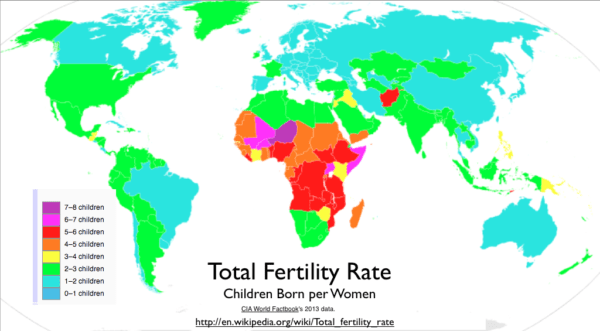

Grégoire Canlorbe: When it comes to challenging the hypothesis that cold winters are natural selectors acting specifically in favor of high intelligence, it is not uncommon to argue that all sorts of natural environment are likely to present challenges requiring high intelligence — and that hunting in the woodlands of Africa is just as hard as hunting in the grasslands of Eurasia. It is added that Arctic peoples such as the Inuit, though encountering the harshest winter conditions, prove to be not especially intelligent; and that, generally speaking, the severity of a given environment does not guarantee intelligence through natural selection. The !Kung live in one of the most arid environments on earth but have low intelligence.

!Kung tribesmen (Credit Image: Staehler / Wikimedia)

In those conditions, a more credible explanation for high intelligence in Europeans and in East Asians would lie in crossbreeding with their Neanderthal cousins as Homo sapiens spread out of Africa and into northern Eurasia. What do you reply to that line of thought?

Peter Frost: A challenging environment doesn’t necessarily reward intelligence. In many cases, the challenges are distributed too randomly over time to be anticipated. In other cases, the payback doesn’t justify the increased mental effort. Harsh environments such as the Kalahari are so resource-poor that increases in mental effort are not rewarded with corresponding gains in food, fuel, and shelter.

In contrast, the Arctic is resource-rich. There is plenty of food, plenty of fuel, and plenty of useful materials for shelter, but those resources cannot be accessed without a lot of mental effort.

Take food. Most hunter-gatherers assign hunting to men and gathering to women. To hunt, a man has to collect, memorize, and manipulate data about space and time, not only his own coordinates but also those of game animals. The quantity of data increases exponentially as a function of hunting distance, which in turn increases as a function of latitude — game animals roam over larger areas in northern environments. So, at high latitudes, his brain has to store huge amounts of spatiotemporal data.

In the Arctic, a woman has few opportunities to gather food, so she specializes in other tasks: meat processing, garment making, shelter building, leather working, fire making, pottery, and ornamentation. If we look at the first modern humans to colonize northern Eurasia, during the last ice age, we see that such specialization led to creation of new tools, a wide range of woven goods, and new ceramic technologies, including use of kilns. This was also noted by Nicole Waguespack in her cross-cultural study of recent hunter-gatherers. She found that women develop new skills and technologies in cultures where they do less food gathering and are more dependent on male providers. She concluded that it was this reorientation of women’s work in the Arctic, and not farming or population growth at lower latitudes, that pushed people to go beyond the primary tasks of getting food. Humans were freed from the mental straitjacket of hunting and gathering. They were now imagining totally new tasks that existed independently of food procurement — what would later become “industry.”

San (also called Bushmen) are an ethnic group of South West Africa. They live in the Kalahari Desert across the borders of Botswana, Namibia, Angola and South Africa. The San have a foraging lifestyle based on the hunting of wild animals and the gathering of veld food. The fact they are hunter gatherers accounts for their nomadic way of life. Their lifestyle is particularly adapted to the hard conditions of the Kalahari Desert. They know where waterholes are located and carry water in ostrich eggshells. They drink water from roots and tubers they find by digging the ground. (Credit Image: © Eric Lafforgue / Whitehotpix)

In addition, for men and women alike, the Arctic favors planning because terrestrial and marine resources are typically seasonal and have to be obtained and processed during a short time to provide a surplus for the lean season. The time constraint is solved by scheduling, by devising specific tools for specific tasks, by using untended devices, such as pits, traps, weirs, and nets, and by digging storage pits down to the permafrost to refrigerate perishables. Again, huge quantities of spatiotemporal data have to be gathered, memorized, and manipulated.

Finally, the cold itself requires cognitive effort. Clothing has to be tailored to retain body heat, and such tailoring requires development of awls, eyed needles, and hide scrapers. Shelters likewise have to be made cold-resistant and built with hearths.

Those demands on cognitive ability are shown by differences in cranial capacity. A team led by Kenneth Beals found a high correlation between cranial capacity and latitude: 0.76 for the Old World and 0.44 for the New World. They concluded that higher latitudes favor more globular heads as a means to retain body heat. Yet their own data showed much lower correlations between latitude and the ratio of body surface to mass, which is the main factor in heat dissipation. If heads are larger at higher latitudes as a means to retain heat, why would heat retention be much less important for the body as a whole?

The cognitive demands of hunting, especially at higher latitudes, are also shown by a decline in cranial capacity after hunting and gathering gave way to farming. Between the Mesolithic and modern times, the decline was 10 percent for men and 17 percent for women. This can be securely demonstrated only for Europeans and East Asians. We do not find this decline in the one non-Eurasian population (Nubians) for whom we have a large enough collection of crania. Did the decline in cranial capacity reflect a decline in intelligence? It was more likely a reorientation of intelligence. In particular, the male mind no longer had to store so much data for hunting. But why, then, was the decline even greater for women? Perhaps men were displacing them in craft production. I can only speculate.

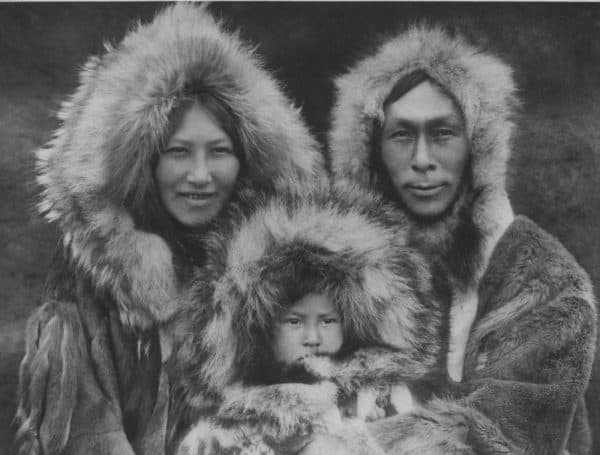

You said the Inuit are not especially intelligent. Actually, they do well on IQ tests. Inuit children in Arctic Quebec perform as well as white children from southern Quebec and even exceed U.S. norms. If we look at adult Inuit who have gone to school and are familiar with test-taking, we see them doing as well as whites and even surpassing them on spatial tasks. Indeed, adult Inuit are reported to have an “extraordinary ability to find their way through what appears to be a featureless terrain by remembering visual configurations […]. According to some reports, such memories persist for long periods of time. Elderly hunters have succeeded in guiding parties through terrain seen only in their youth.”

An Inuit family in 1928. (Credit Image: Edward S. Curtis via Wikimedia)

That extraordinary memory for detail, as expressed in contemporary Inuit art, came to the attention of L.L. Cavalli-Sforza, a leading geneticist. In the late 1980s, he organized a project with our university and Queen’s on the genetic and cultural bases of Inuit spatial intelligence. He hoped to show how gene-culture coevolution has created cognitive differences between human groups. Then he dropped the project, for “health reasons.”

I don’t wish to romanticize the Inuit. They have serious problems with alcohol abuse and a high rate of youth suicide. In short, they are ill-suited to the Western model of sedentary living, individualism, and superficial interaction with other people, particularly kinfolk. Young Inuit feel useless in that environment and develop suicidal thoughts. In my opinion, they should disengage from Western culture.

So should we. Yes, we can better tolerate the toxic effects of asociality and weak kinship, but that tolerance has been pushed to the limit and beyond. We’re now in the red zone.

Finally, you asked whether intermixture with Neanderthals was key to the evolution of human intelligence. The Neanderthals had to adapt to the cold. Perhaps they provided modern humans with intelligence-boosting alleles.

It’s a nice theory, but the facts are less obliging. If we look at Neanderthal admixture in our genome, we see that it is disproportionately inactive. There has been selection to remove genetic material that actually does something. Should we be surprised? The Neanderthals adapted to a similar natural environment, but they did so not only in different ways but also in a different body. Something useful in a Neanderthal body is probably not so useful in ours.

Another thing. There is Neanderthal admixture in all of the indigenous peoples of Europe, Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania, and the Americas. Europeans are actually the least Neanderthal of all those populations (Oceanians are the most). Those populations also differ a lot in technology and social complexity. So it’s not obvious that Neanderthal admixture has had much effect on mind and behavior.

Interview continues below…

References

Beals, K.L., C.L. Smith, S.M. Dodd, J.L. Angel, E. Armstrong, B. Blumenberg, F.G. Girgis, S. Turkel, K.R. Gibson, M. Henneberg; et al. (1984). Brain size, cranial morphology, climate, and time machines. Current Anthropology 25: 301-330.

Berry, J.W., and L.L. Cavalli-Sforza. (1986). Cultural and genetic influences on Inuit art. Report to Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Ottawa.

Frost, P. (2011). Suicide and Inuit youth. The Unz Review. December 10.

Frost, P. (2014). L.L. Cavalli-Sforza. A bird in a gilded cage. Open Behavioral Genetics, March 28.

Frost, P. (2019). The Original Industrial Revolution. Did Cold Winters Select for Cognitive Ability? Psych 1(1): 166-181.

Hawks, J. (2011). Selection for smaller brains in Holocene human evolution. arXiv:1102.5604 [q-bio.PE]

Henneberg, M. (1988). Decrease of human skull size in the Holocene. Human Biology 60: 395-405.

Kleinfeld, J.S. (1973). Intellectual Strengths in Culturally Different Groups: An Eskimo Illustration. Review of Educational Research 43(3): 341-359.

Sankararaman, S., S. Mallick, N. Patterson, D. Reich, S. Djebali, H. Tilgner, G. Guernec, D. Martin, A. Merkel, D.G. Knowles, et al. (2016). The combined landscape of Denisovan and Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans. Current Biology 26(9): 1241-1247.

Taylor, L.J., and G.R. Skanes. (1976). Cognitive abilities in Inuit and White children from similar environments. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science 8(1): 1-8.

Waguespack, N.M. (2005). The organization of male and female labor in foraging societies: Implications for early Paleoindian archaeology. American Anthropologist 107: 666-676.

Wright, S.C., D.M. Taylor, and K.M. Ruggiero. (1996). Examining the Potential for Academic Achievement among Inuit Children: Comparisons on the Raven Coloured Progressive Matrices. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 27(6): 733-753.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Aside from Spartans (whom the other Greeks thought mentally and culturally backward), it seems that Classical Greece was characterized by high levels of mean intelligence and exceptional intelligence and by a pluralistic and heroic approach to cognitive life, in which there was intellectual innovation and competition between different intellectual leaders. This contrasts with the traditionally conformist approach of knowledge in China or the Middle East. How do you make sense of the Golden Age of Greece?

Credit Image: Sonse / Wikimedia

Peter Frost: A team led by Michael Woodley of Menie has found that alleles for educational attainment gradually became more frequent between 4,560 and 1,210 years ago in Europeans and Central Asians. He’s now looking specifically at ancient Greek DNA. Preliminary results show an increase in the same alleles from Neolithic to Mycenaean times, followed by a decrease between then and the modern era.

What was driving that increase? I don’t know. To explain the Golden Age of Greece, we must understand what was happening before, particularly in terms of demography. I suspect there was a process like that of medieval and early modern England, i.e., a steady increase in people who made their living from trade. Trade seems to select for intelligence, particularly numeracy and literacy.

Once people can read commercial contracts they can read philosophy. The doors are wide open to further intellectual improvement.

You asked why the approach to knowledge was less conformist in ancient Greece than in China. In a word, the Chinese state “nationalized” intelligence through the imperial examination for entry into the state bureaucracy. That exam had an impact on the Chinese people not only intellectually but also demographically and perhaps genetically. It’s true that only 1 percent of the population reached the top degree of chin-shih or the lesser degree of chu-jen, but success at lower levels also brought benefits, if only prestige, and the beneficiaries were much more numerous. Anyway, let’s assume that benefits accrued only to the 1 percent who held those degrees. Let’s also assume that with each passing century, the descendants of that original 1 percent became only twice as numerous. In six centuries, they would be the majority.

I can already hear the criticisms. “But some of them would’ve married into the rest of the population! You’re assuming the population was stationary! And you’re forgetting regression to the mean!” Well, OK, but in the meantime there would have been new cohorts of degree-holders. Whatever the line of criticism, my basic point still stands. Steady growth has a dramatic impact over the long term, even from a small base. In this case, the long term was quite long. The imperial examination began some 1400 years ago, reached its apogee almost a thousand years ago, and ended at the dawn of the 20th century.

Thus, over the long term, the imperial examination could have influenced the psychological makeup of the Chinese people, both in their average level of intelligence and in the nature of their intelligence. Intellectual conformity was favored. Degree-holders were chosen for their ability to memorize existing knowledge and present it in standardized ways, particularly classic works of prose and poetry and neo-Confucian orthodoxy. Over the centuries, attempts were made at reform, notably by eliminating questions on poetry and introducing more practical subjects, but such measures ignored a more serious shortcoming.

A statue of Confucius at the Beijing Temple of Confucius (Credit Image: Mx. Granger / Wikimedia)

Exams, by their very nature, sanctify existing ways of thinking. People are penalized for giving “wrong” answers that may, in fact, be logical and defendable. Ultimately, doubt itself is penalized, since it distracts from the all-important task of knowing the “right” answers.

Interview continues below…

References

Unz, R. (2013). How Social Darwinism made modern China. The American Conservative, March/April, pp. 16-27.

Woodley of Menie, M.A., S. Younuskunju, B. Balan, and D. Piffer. (2017). Holocene selection for variants associated with general cognitive ability: Comparing ancient and modern genomes. Twin Research and Human Genetics 20: 271-280

Woodley of Menie, M.A., J. Delhez, M. Peñaherrera-Aguirre, and E.O.W. Kirkegaard. (2019). Cognitive archeogenetics of ancient and modern Greeks. London Conference on Intelligence.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UES_tpDxz9A

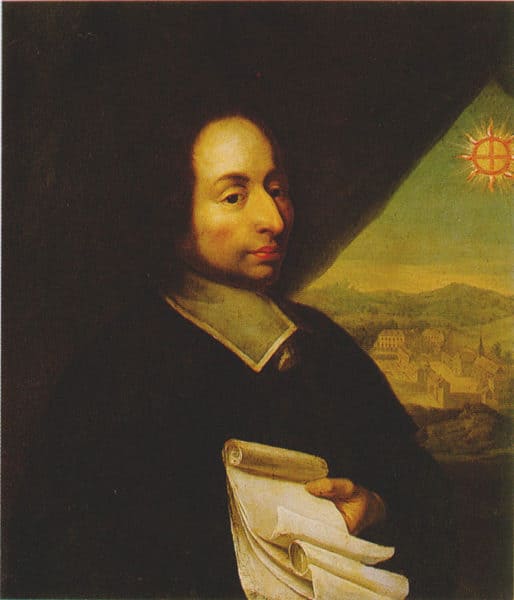

Grégoire Canlorbe: You have the following words by Blaise Pascal inscribed in the sidebar of your blog: “Man is neither angel nor beast; and the misfortune is that he who would act the angel acts the beast.” How does that quote relate to your work as an evolutionary anthropologist?

Peter Frost: I learned that quote from Michel Cabanac, an evolutionary psychologist and a strong Christian. That might sound like a contradiction, but it isn’t.

Portrait of Blaise Pascal

Evolutionary social scientists grasp the importance of religion better than many evangelists and certainly better than conservative politicians. We need religion, and we feel that need in our flesh and bones.

Religiosity is partly innate. Twin studies have shown that the genetic component is between 25 and 45 percent, but the non-genetic component includes literally everything else, like errors in understanding the question and in collecting the data. We therefore have an innate need to internalize norms of correct behavior, particularly our notions of right and wrong. This need seems to vary from one person to another, and perhaps from one population to another, but I won’t go into that here.

We used to meet our need for moral guidance by looking to religion. The Church taught us how to behave. Its teachings, though imperfect, had at least been tried and tested over many generations. Today, with the decline of Christian faith, our culture is being reprogrammed with new behavioral norms that have never proven their worth. These are not just things that are wonderful in theory but terrible in practice. Many are terrible in theory and in practice. They get accepted because their proponents have the megaphone.

Michel Cabanac was appalled by this reprogramming of post-Christian society. We still have an innate need for moral guidance, but it is now being pushed into new channels and made to serve new ends, often cynically so.

Interview continues below…

References

Bouchard, T.J. Jr., (2004). Genetic influence on human psychological traits: A survey. Current Directions in Psychological Science 13: 148-151.

Lewis, G.J. and T.C. Bates. (2013). Common genetic influences underpin religiosity, community integration, and existential uncertainty. Journal of Research in Personality 47: 398-405.

Grégoire Canlorbe: Thank you for your time. Is there something you would like to add?

Peter Frost: I’m an armchair anthropologist. I’ve done research, but the above material comes overwhelmingly from other people. Some of them are still active, others are no longer of this world, and still others have fallen silent for reasons of their own. I understand the reasons. We are going through difficult times, and the worst may be yet to come. But all of this will pass.