Sam Houston and the Alamo Avengers

Sinclair Jenkins, American Renaissance, January 24, 2020

Brian Kilmeade, Sam Houston and the Alamo Avengers, Penguin Random House, 2019, 288 pp., $14.00.

Americans are spoiled with an exceptionally heroic history. Virginia, for example, was promoted by naval commander and explorer Sir Francis Drake, the English diplomat and early imperialist Richard Hakluyt, and the quintessential Renaissance man, Sir Walter Raleigh. Jamestown was founded by settlers who managed survive terrible winters and Native attacks meant to exterminate them. In New England, Pilgrims and Puritans carved out God-fearing colonies. They, too, had to fight for their lives during King Philip’s War, during which Indians burned Medford, Providence, and Brookfield. The New England Confederation got little-to-no help from London but won the war against a more numerous foe and created a uniquely American style of war, rangering.

While most citizens pay lip-service to the heroism of the Founding Fathers, the Left routinely dismisses them as nothing but slaveholders. It is therefore refreshing that Mr. Brian Kilmeade, one of the presenters on President Trump’s favorite television show, Fox & Friends, has published a pro-American history. His Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers tells the story of the Texas Revolution (1835 – 1836) and the defeat of General Santa Ana’s Mexican Army. Mr. Kilmeade explains that the Texians (the term “Texan” did not come into use until after the Republic of Texas was annexed by the United States in 1845) were justified in rebelling and were better fighters. Judging by its popularity on Amazon and on BarnesAndNoble.com, readers like heroic histories.

Like a lot of the men who moved to Mexican Texas in the early 19th century, the title-character, Sam Houston, was what Mr. Kilmeade calls a “second chance man.” As a teenager in Virginia, Houston fought as a junior officer during the War of 1812. He enlisted as a private in the army of General Andrew Jackson, who shared the same Scots-Irish blood. After the Red Stick Creek massacre of American settlers at Fort Mims in the Mississippi Territory (now in Alabama), Jackson’s army put down the Indian menace. Lieutenant Houston led his men in a charge and was seriously wounded by a musket ball in his upper thigh. Mr. Kilmeade notes that his surgeon believed he “would not survive the night,” but Houston proved him wrong. The victory over the Red Stick Creek denied the British a potential ally in the Deep South. [1]

Houston recovered from his wound at Jackson’s Hermitage plantation near Nashville, where “Old Hickory” became Houston’s surrogate father. Jackson groomed Houston for politics, and Houston won a seat in Congress. In 1829, the 35-year-old married the young Nashville socialite Eliza Allen, but three months later, she left him after Houston questioned her faithfulness. In a deep depression, Houston went to live with the Cherokee (he had run away to live with them before at age 16). Mr. Kilmeade quotes Houston, who once said that he preferred “the wild liberty of the Red Men better than the tyranny of his own brothers.” [2] The Cherokee gave Houston two nicknames: Co-lon-neh (“the Raven”) and Oo-tse-tee-Ar-dee-tah-skee (“the Big Drunk”). [3] The latter was more descriptive. Houston married a Cherokee woman and for a time ran a general store in Arkansas. He did not have the obvious makings of a national hero.

In the meantime, important things were happening in Texas. The Spanish and then the Mexicans invited American colonists to settle the sparsely populated area. By 1820, thanks to the passage of a new land act by Congress, Americans flocked to Mexico, where “a settler could buy land for 12 1/2-cents per acre.” [4] The Mexicans initially welcomed this: Americans were known for being hardworking and skilled in combat. Tough settlers were needed because the Comanche also claimed Texas.

“Gone to Texas” (often abbreviated as G.T.T.) became a common phrase in the South during the 1820s and 1830s. Some Northerners were drawn to Texas as well. Connecticut-born Moses Austin became one of the earliest Texas empresarios (large land owners), and his son, Stephen F. Austin, led the “Old 300” settlers to the first American colony. Other G.T.T. men included Jim Bowie, Davy Crockett, Benjamin Milam, William Barrett Travis, and Erastus “Deaf” Smith. Mr. Kilmeade portrays all these Anglos as rough men who went to Texas to redeem themselves. Bowie, born in Kentucky to a poor farmer, served in Jackson’s army during the War of 1812 before killing a man in a knife fight. [5] He fled to Texas, where he converted to Catholicism and married a Tejano woman.

Benjamin Rush Milam was a Kentucky boy who served with the Kentucky Infantry in the War of 1812. He moved to Texas and established Milam’s Colony between the Guadalupe and Colorado Rivers. “Deaf” Smith, who became the premier scout and spy of the Texian Army, was born in New York’s Hudson Valley. Hard-of-hearing from birth, Smith moved to Texas early (in 1821) and also married a local Mexican woman. Arguably the most famous of the early Anglo settlers, “Davy” Crockett came from the Virginia frontier. Crockett had served under Jackson during the war against the Red Stick Creek, made a name for himself as a big-game hunter, and, before coming to Texas, served as a populist “poor man” politician in both the Tennessee General Assembly and the US Congress. [6]

When the Texas Revolution came in 1835, the main opponent of the Texians was Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, the son of a wealthy military family in Veracruz. As a teenager, he fought against Mexican independence as a member of the Royal Spanish Army. When the war turned against Spain around 1821, Santa Anna changed sides, and eight years later was hailed as a Mexican hero for turning back a Spanish invasion attempt. Santa Anna was elected president in 1833 because he was a popular war hero, much like Andrew Jackson. Vain and brutal, Santa Anna, who enjoyed calling himself the “Napoleon of the West,” suspended all constitutional limitations on his authority and began ruling as a military dictator. [7] This did not sit well with Mexico’s Liberals or with Texas’s Anglos. War was inevitable after Santa Anna arrested Stephen Austin and declared the Texians in violation of the 1824 Mexican Constitution because many had refused to convert to Catholicism (a requirement for Mexican citizenship).

Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers argues that it was Santa Anna’s tyrannical rule that inspired Texians to take up arms. A generation ago, this was the standard opinion, but modern “scholars” emphasize slavery and slavery’s expansion as the motive. The Republic of Texas and the State of Texas had cotton plantations and slavery, whereas Mexico outlawed slavery in 1829. Mr. Kilmeade mentions slavery only once: as the reason Northerners opposed annexing Texas in 1836.

Mr. Kilmeade’s book goes against the current scholarly consensus in another way by emphasizing the fighting in the Texas Revolution. Military history is too patriarchal, too conservative, and maybe too interesting for the academic Left. The only thing keeping it alive are general readers — the people who are making Mr. Kilmeade’s book a best-seller.

Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers notes that at Gonzales, Goliad, and Concepcion, untrained militiamen and volunteers defeated professional Mexican soldiers. At the siege of the Alamo, hundreds of Texians held out for days against thousands of Mexican infantry and cavalry. After the defeat, the Texian soldiers who died defending the former Catholic mission were thrown into large funeral pyres [8]. After the next major battle at Goliad, Colonel James Fannin and over 400 of his men were executed after being promised safe passage to New Orleans if they surrendered.

Fall of the Alamo, by Robert Jenkins Onderdonk, 1903.

Santa Anna’s savagery reinforced Texian resolve. After the Alamo, the idea that Anglo Texas could still somehow be an autonomous state of Mexico died. Fortunately for Texas and the United States, it took the ragtag Texians only 18 minutes to defeat Santa Anna’s army at the Battle of San Jacinto. Santa Anna tried to flee dressed as a Mexican peasant, but he was captured by Texian privates and forced to sign a peace treaty recognizing Texas independence. Santa Anna, who had killed hundreds of Anglo rebels, became an enthusiast for Texas independence, and went to Washington, D.C. in 1836 to make the case for a separate Republic of Texas [9] — probably because he thought it would be easier to take it back if the US didn’t annex it. Santa Anna again became president in 1841 and started threatening the independent republic. On March 5, 1842, he sent in an invasion force of 700 men that briefly occupied San Antonio, causing panic throughout the state. Three years later, Mexico and the United States were at war.

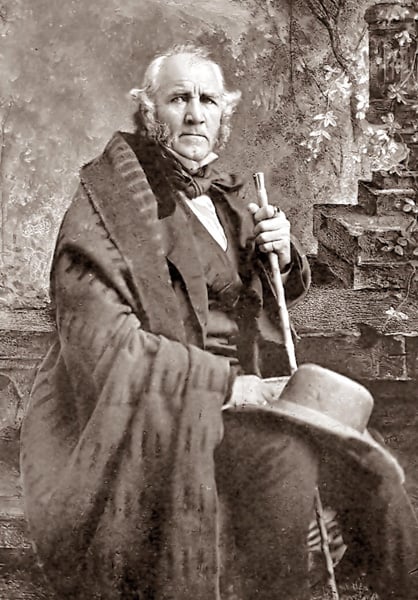

Mr. Kilmeade’s story ends with independence. Houston and his fellow rebels lived to see Texas go from a republic to a state before rebelling again in order to join the Confederacy. Houston was a Unionist, but his first love was always Texas. When he died on July 26, 1863, his last words were reportedly, “Texas! Texas!” [10]. Mr. Kilmeade writes that Houston and the other Texians not only gave us the symbol of the Alamo, but helped define the American character. He does not describe that character; he doesn’t have to. It was rugged independence, manliness, and a hatred of illegitimate authority. Now, massive immigration, both illegal and legal, is killing the spirit of Texas, maybe for good.

Sam Houston

* * *

[1]: Kilmeade, Brian, Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers: The Texas Victory That Changed American History (New York: Sentinel, 2019): 3.

[2]: Kilmeade, Sam Houston & and the Alamo Avengers, 6.

[3]: Kilmeade, Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers, 7.

[4]: Kilmeade, Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers, 9.

[5]: Kilmeade, Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers, 21.

[6]: Kilmeade, Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers, 98-99.

[7]: Kilmeade, Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers, 24.

[8]: Kilmeade, Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers, 138-139.

[9]: Kilmeade, Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers, 222-223.

[10]: Kilmeade, Sam Houston & the Alamo Avengers, 230.