American Demagogue

F. Roger Devlin, American Renaissance, November 2, 2018

Carl F. Horowitz, Sharpton : A Demagogue’s Rise, 2018 Expanded Edition, CreateSpace, 2018, 370+xvii pages, $16.99, softcover

Carl F. Horowitz is a policy analyst and editor at the National Legal and Policy Center, a private non-profit founded in 1991 to promote “ethics and accountability in American public life.” He has written many articles and a substantial background paper on Al Sharpton, and when Mr. Sharpton’s profile rose after Barack Obama became president, Mr. Horowitz expanded the background paper into a book that was published in 2015. A second, updated edition brings the story up to date with five new chapters and adds material to earlier chapters.

The author resists the temptation to caricature a figure who often veers into self-parody, but the best he can find to say in his subject’s favor is this: “[Mr. Sharpton is] by all appearances a decent father to his two daughters; he has spoken out against black ‘gangsta’ culture and its accompanying misogyny; [and] his desire to improve education is genuine.” At the same time, Mr. Horowitz faults many of Sharpton’s critics for reducing him to:

a cartoonish caricature far removed from everyday black experience, a power-mad loon who “betrayed” Martin Luther King’s dream of peace, love and understanding. This view is way off base. Quite aside from the fact that it was King who gave a young adolescent Sharpton his start in the world of activism, Sharpton wouldn’t have lasted on the national stage for thirty weeks much less thirty years if he were isolated from fellow blacks.

Mr. Sharpton’s National Action Network has about 100 chapters across America, and Mr. Horowitz reports that “he is on a first name basis with hundreds, if not thousands of black clergymen around the nation.” A 2013 Zogby poll found American blacks identify far more strongly with Mr. Sharpton than with any other black leader, with over twice the support of runner-up Jesse Jackson. Al Sharpton is well within the mainstream of black opinion: His mission and methods accurately reflect the views of millions of ordinary black Americans.

Early life

Alfred Charles Sharpton Jr. was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1954, the son of a building contractor. The family was not poor: “[A]t one point,” he recalls, “my father was doing so well he bought two Cadillacs every year, one for my mother, one for him.” Mr. Sharpton boasts that he was already formidable as a baby: “I yelled when I was hungry. I yelled when I was wet. I learned before I got out of the maternity ward that you’ve got to holler like hell sometimes to get what you want.”

Mr. Sharpton began preaching at the age of four. Many black ministers are barely literate: The main qualifications for conducting the ecstatic style of worship service blacks favor are an outgoing personality and the ability to connect with the congregation. The young Sharpton had these qualities in abundance, and soon had worshipers flocking to Brooklyn’s Washington Temple of God in Christ to hear the “wonder boy preacher.” Mr. Sharpton was ordained at the age of nine, and enjoyed annoying his school teachers by signing homework with the title “Reverend.”

Also when he was nine, Mr. Sharpton’s father ran off with his 18-year-old half-sister, his mother’s daughter from a previous marriage. Mr. Sharpton’s mother took the rest of the family to a cheaper apartment; she worked as a maid and went on public assistance. This was traumatic for Mr. Sharpton, who has acknowledged that much of his early career was a search for a substitute father.

Four mentors

Accordingly, the young Sharpton worked as an understudy to four prominent older black figures: Adam Clayton Powell, Martin Luther King, Jesse Jackson, and James Brown. Mr. Horowitz’s account of these apprenticeships gives us a better understanding of Mr. Sharpton, and makes it clear how mainstream his beliefs and practices are — for blacks.

Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (1908–72) was a Baptist minister and politician who got his start in activism in the 1930s as chairman of something called the Coordinating Committee for Employment. He organized mass meetings and rent strikes, and threatened boycotts against white employers who did not hire enough blacks. Among his targets were the 1939 New York World’s Fair, the city transit authority, and white-owned Harlem drug stores. In 1944, Powell won election to a new congressional seat that included Harlem. Mr. Horowitz writes:

He was instrumental — far more than people today realize — in generating support for progressive legislation, especially after becoming chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee in 1961. Many of President Kennedy’s New Frontier and (especially) President Johnson’s Great Society initiatives might not have come to fruition without Powell’s persistence.

Mr. Sharpton read a biography of Powell as a child and began attending his church services. He later described his first glimpse of the man:

I’ll never forget the first time I actually laid eyes on Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. He walked out of the side door into the sanctuary in his robe with that straight, long posture. I thought I had seen God . . . . He had this magnetism and this majestic air. He was very elegant, but at the same time defiant — a real man’s man.

At their first meeting, Mr. Sharpton discovered that his hero had already heard of the “boy preacher from Brooklyn,” and he quickly became “the kid” in Powell’s entourage. Powell taught Mr. Sharpton what can only be called “shamelessness:” “What I learned from Powell about leadership . . . is that you can’t care what people think.” Powell once told him: “What might appear recklessness on my part is really defense. They can never threaten to expose me, because I expose myself.”

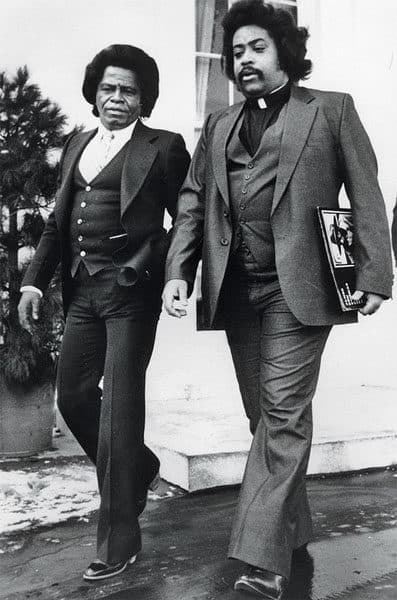

Adam Clayton Powell with Malcolm X.

Powell enjoyed flaunting his wealth, but much of it turned out to come from illegal withdrawals from congressional committee funds. In March 1967, the House of Representatives voted 307-116 to expel him. Powell simply won the seat back in the special election that followed. When his House colleagues stopped him from taking his seat, he sued and was reseated in June 1969 after the US Supreme Court found in his favor. Powell taught Mr. Sharpton hatred for “Uncle Toms,” or blacks who show weakness. Powell told Mr. Sharpton: “These yellow Uncle Toms are taking over the blacks in New York. Don’t you stop fighting. If you want to do something for [me], get rid of these Uncle Toms.”

The second important influence on Mr. Sharpton was Martin Luther King, Jr. Mr. Sharpton’s first employment was as a youth minister in the Brooklyn offices of Operation Breadbasket, a multi-city boycott managed by King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference against white small businesses that failed to hire enough blacks or buy from black suppliers. “I met Dr. King a couple of times,” recalls Mr. Sharpton. “He knew me as ‘the boy preacher.’ When he would see me, he would say, ‘There goes that boy preacher!’ and a big grin would break out over his face.”

Although their personal acquaintance was slight, Mr. Sharpton was strongly influenced by the documentary King: From Montgomery to Memphis, which he watched when he was 14. As Mr. Horowitz explains:

He learned from King the importance of direct action as a basis for negotiation. In ‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail,’ King wrote: ‘[T]he purpose of direct action is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door for negotiation.’ This is Sharpton’s view. And like King, who had been accused of showboating even by his allies, Sharpton maximizes events for dramatic effect, always with media coverage in mind.

Although he never endorsed violence, King negotiated with thinly veiled threats that things could get out of hand if black demands were not met. Mr. Horowitz calls this “a brand of nonviolence that was more conditional than principled.” “No Justice, No Peace,” the threat that is the official slogan of Mr. Sharpton’s National Action Network, is based directly on King’s own methods. King also endorsed racial quotas and reparations.

Mr. Horowitz notes, however, that “King at least analyzed a situation dispassionately before taking action. Unlike Sharpton, he did not automatically take the word of blacks or their families declaring themselves to be victims of injustice.” And King was a man of modest tastes, whereas Mr. Sharpton always goes first class. This has not prevented the King family from endorsing him; Coretta Scott King described Mr. Sharpton as “a voice for the oppressed, a leader who has protested injustice with a passionate and unrelenting commitment to nonviolent action in the spirit and tradition of Martin Luther King, Jr.” King’s eldest son, Martin Luther King III, has worked frequently with Mr. Sharpton. Had he lived to see the adult Sharpton in action, Horowitz conjectures that:

King might scold Sharpton for his behavior from time to time, much as a father might admonish an impetuous son, but each would seek the same results. Al Sharpton has not betrayed Martin Luther King. What unites the two, in viewpoint and style, is far more powerful than what divides them.

Conservative claims to the contrary reflect either ignorance or self-deception.

Mr. Sharpton’s association with his third mentor, Jesse Jackson, has been more personal. Like Mr. Sharpton, Mr. Jackson got his start in King’s Operation Breadbasket. As head of the Chicago office, Mr. Jackson occasionally visited his counterparts in New York, where he did not fail to notice the “boy preacher” working as a youth minister. Mr. Sharpton calls the older man “my teacher,” and remembers:

Right away we identified with each other. Jesse was younger than the other preachers of that time. He wouldn’t even wear a suit and tie. Jessie always used to wear a medallion . . . . And he sported the buck vest and a big ‘fro. I later learned that he had been born out of wedlock and came from a broken home, like I did. He didn’t come out of the seminary, wasn’t one of those collegiate types. Jesse was a regular . . . . We just hit it off. I became his protégé. I started wearing medallions like his and I used to try to talk like him.

Mr. Jackson got the help of a violent Chicago gang to intimidate white business owners into making “contributions” to Operation Breadbasket. A Chicago criminal justice official describes how one gang leader operated:

[Jeff Fort] would make the rounds of the small business owners, telling them that if they didn’t contribute, ‘We’ll burn you down.’ It was a shakedown pure and simple. They called themselves community organizers. In those early days, Jackson boasted of his ties to the gangs.

Operation Breadbasket grew into a multimillion-dollar extortion racket with more than 30,000 members nationwide, and Jesse Jackson became its national director in 1969. He appointed Mr. Sharpton youth director of the New York chapter.

By 1971, both men had left the organization. Mr. Jackson formed what would come to be known as the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, while Mr. Sharpton, with the help of some older Harlem leaders, formed the National Youth Movement (NYM). This group promoted the newly invented black holiday Kwanzaa and staged sit-ins. According to New York State prosecutor Victor Genecin, however, the NYM was “never anything more than a one-room office in Brooklyn with a telephone and an ever-changing handful of staffers who took Al Sharpton’s messages and ran his errands.”

Mr. Sharpton admired Mr. Jackson so greatly that he assembled a videotape library of Mr. Jackson’s public appearances. “Jesse Jackson is probably the smartest person I know,” Mr. Sharpton wrote; “there’s no one I know who has a more brilliant, fertile mind.” And Mr. Sharpton paid close attention as Mr. Jackson went from shaking down small-time Chicago shopkeepers to getting huge keep-the-peace “agreements” from some of the biggest corporations in America: Texaco, Nike, Toyota, and Anheuser-Busch. Jesse Jackson was among the first to discover how weak-kneed even the wealthiest and most powerful whites could be if they were accused of “racism.”

The young Sharpton’s fourth mentor, and the most influential in his own estimation, was the “Godfather of Soul” James Brown. As a child, Mr. Sharpton’s father had taken him to the Apollo Theater in Harlem to admire “Brown and his band’s raw energy, precision playing and tight choreography.” The men first met about a year after Mr. Sharpton graduated from Brooklyn’s Tilden High School. Mr. Sharpton recalls:

In 1973, when I was eighteen, James heard about my National Youth Movement and decided he wanted to help me raise money by doing a benefit concert. James seemed to really like me and took me under his wing. He started inviting me to his shows to help out, eventually bringing me all around the world with him and even appointing me his manager because he knew he could trust me. Our relationship became like father and son.

Mr. Sharpton made Brown’s musical show the main focus of his activities for the rest of the 1970s, even as he was setting up NYM chapters around the country. It was Brown who persuaded Mr. Sharpton to shorten his name from “Alfred” to “Al,” and it was through Brown that Mr. Sharpton met his wife, a backup singer in the band named Kathy Jordan. Mr. Sharpton recalls Brown teaching him the importance of having lots of money: “Reverend, you gotta go for the hog.” Mr. Sharpton has also written of him:

The person who had the greatest influence over me and is most responsible for the man I am today is James Brown. He had more impact on my life than any civil rights leader. What I learned from him makes it possible for me to do the things I do today. He taught me self-respect, dignity, and self-definition.

Yet Brown was also a bully:

‘James was bossy and paranoid,’ recalled former trombonist Fred Wesley. ‘I didn’t see why someone of his stature would be so defensive. I couldn’t understand the way he treated his band, why he was so evil.’ He would fine members for being late, missing notes, violating his dress code or engaging in back talk. This treatment eventually prompted a permanent walkout in 1969 of nearly all members of his band.

Brown was also a criminal. He did a stint in reform school after a conviction for burglary at age 16. There are many stories of his abusing women, and he once went after a musical rival with a gun; several bystanders were injured, but Brown was never prosecuted. The most notorious criminal incident of his career was in 1988, after Mr. Sharpton had parted ways with him. High on PCP and armed with a shotgun, Brown threatened attendees at an insurance seminar held in a building he owned. When the police arrived, he led them on a high-speed chase across two states that ended only after three of the tires on his cars were shot out. Convicted of assaulting a police officer along with various drug and driving offenses, Brown spent 15 months in prison and another ten on work release.

Mr. Sharpton couldn’t understand what all the fuss was about: “James Brown in jail was the biggest cultural insult to a race that has ever happened.” Perhaps it was from Brown, Mr. Horowitz suggests, that Sharpton learned that:

a person can get away with illegal and outrageous acts if he is sufficiently famous, intimidating, or supportive of the ‘right’ causes. In 2003, the State of South Carolina granted James Brown a full pardon for prior convictions. That same year, the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts honored him with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

Mr. Sharpton left Brown’s entourage in 1980, but the men remained close for several years.

FBI informant

Although he has tried to deny it, during the ’80s, Mr. Sharpton worked for the FBI. There is a videotape of him apparently agreeing to a cocaine deal with an undercover agent in 1983; parts of it were broadcast on national television in 2002. This sting may have been designed to force Sharpton to turn informant. He went on to use a concealed microphone to get information on organized crime involvement in the New York music business. Based on this information, the authorities were able to get court authorization to bug social clubs, cars, and phone lines associated with the Genovese crime family, leading to several convictions in the late 1980s.

Mr. Sharpton has since claimed that the government was trying to shut down his “civil rights” advocacy, but he may have less cause for embarrassment over these activities than nearly any others in his career; involuntarily or not, he helped put away genuine criminals. As Mr. Horowitz notes, “that’s more than can be said for his campaigns to railroad innocent whites.”

First campaign: Bernie Goetz

Mr. Sharpton’s first public campaign targeted “subway vigilante” Bernhard Goetz, following a script he uses to this day. In Mr. Horowitz’s words:

All it takes to get him to swing into action is a report of a white-on-black crime (which he assumes happened) or a black-on-white crime (which he assumes did not happen) that can serve as a pretext to intimidate whites. The facts of a given case don’t matter — or at any rate, don’t matter nearly as much as the possibility of affirming an overarching narrative of black suffering (at the hands of whites).

Bernie Goetz shot and wounded four young black men who tried to mug him on a New York subway train in December 1984. He became something of a hero to New Yorkers exasperated by crime, and enjoyed the moral support of many blacks, including Roy Innis of the Congress of Racial Equality. Mr. Sharpton took the lead in pressing for criminal charges:

I called a news conference on the steps of City Hall and denounced the situation . . . . I went to his apartment house in 14th St. and immediately we started getting press coverage. We held prayer vigils; we went to all the court proceedings. I had learned those things from the civil rights movement. . . . We had never gone to white people’s houses or to their neighborhoods to picket and march. We created drama.

A first grand jury declined to indict Mr. Goetz on anything but illegal gun possession. Mr. Sharpton went on with his demonstrations. A second grand jury indicted Mr. Goetz for several felonies, including assault and attempted murder, but the jury convicted him only on a weapons charge. A civil suit claiming Mr. Goetz shot the men out of bias against blacks eventually resulted in a $43 million award to one of the muggers. Unable to pay, Goetz declared bankruptcy.

Howard Beach

Even before Goetz’s criminal trial had finished, Mr. Sharpton was on to his next project. In December 1986, some white teenagers were driving a girl home after midnight in the Howard Beach neighborhood of Queens when three black men stepped in front of their car. The driver slammed on the breaks and shouted “What the hell. I almost hit you — get out of the way!” One of the black men later admitted to saying “fuck you, honky.” Witnesses also say he banged on the car, stuck his head through a window and spat in the face of one of the whites. Another of the black men reportedly flashed a knife.

The whites, furious, dropped off the girl and returned to the scene with baseball bats. One of the black men got away. Another, Frederick Sandiford, got a beating and needed five stitches. A third, Michael Griffith, with a “near-lethal level” of cocaine in his system, was chased for a while and later crawled through a hole in a fence onto a parkway where he was struck and killed by a car. The whites had stopped chasing him before this happened.

These facts only came out later. The initial story was that ten whites accosted the three black men in a pizzeria and asked “What are y’all doing in this neighborhood?” They then attacked them for being black. Mayor Ed Koch called it “a modern lynching.”

Mr. Sharpton talked to Mr. Sandiford and to Griffith’s widow, and concluded that this was “clearly a racial killing.” Within a week he was leading 1,200 angry marchers through the Howard Beach neighborhood calling for a boycott of local businesses. Mr. Horowitz notes: “As a matter of principle, Sharpton always has refused to obey local laws requiring a permit to march. For him, marching in the street, even if it impedes traffic, is a ‘human right.’ ” Mr. Sharpton also set up Mr. Sandiford and the Griffith family with lawyers. They urged Mr. Sandiford not to cooperate with the investigation, then accused investigators of conspiring to deny him an opportunity to give his version of events. One of the lawyers, without evidence, accused the police commissioner, a black man, of a cover up, and charged that the motorist who accidentally struck Griffith was part of a murder conspiracy.

According to Mr. Sharpton and his lawyer friends, the city police and criminal justice system were so “racist” that a state-appointed special prosecutor was needed. The governor appointed one: a white man. Mr. Sharpton’s crew objected, but eventually relented. The three principal white defendants were convicted and ended up serving between 12 and 15 years behind bars.

One of the defendants turned out to have had a black girlfriend with whom he had broken up about a month before the incident. She later commented: “Jon was railroaded for two reasons: the pretrial publicity and the fact that the judge knew the prosecution had to win because they were afraid the city was going to blow up.” Mr. Horowitz summarizes:

The notion that the whites were out-of-control ‘racists’ on the prowl for blacks to beat up is poppycock. Those youths were looking for specific blacks who had threatened them. But Sharpton and [his] legal team argued that the entire Howard Beach neighborhood, supposedly a microcosm of racist America, ought to be put on trial. And they chose to antagonize that neighborhood, all the while making absurd and paranoid allegations that undermined the prosecution.

Tawana Brawley

Of all Mr. Sharpton’s campaigns, his promotion of the Tawana Brawley rape hoax has gone farthest to define him, both because his malfeasance was so gross and obvious, and because it was when millions of Americans first heard of him. On the morning of November 28, 1987, a woman in Wappinger Falls, New York, about an hour’s drive north of New York City, noticed a young black girl climbing into a garbage bag and lying still on the cold, muddy ground. She alerted the Sheriff’s Department and officers arrived to discover the 15-year-old smeared with feces, her clothing torn and burned, and covered with racial insults written in charcoal. She said she had been abducted by at least three white men, at least one of whom was wearing a badge, and taken to a wooded area where she was assaulted and raped over a four-day period. She was taken to a hospital in nearby Poughkeepsie where a Sheriff’s detective arranged for a rape examination.

It did not take long for Mr. Sharpton to become the Brawley family’s “adviser.” He called in his lawyer pals from the Howard Beach incident, edging out the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. The government was covering for the assailants, they charged, who included Scott Paterson, a State Trooper, Harry Crist, a police officer, and Steven Pagones, an assistant prosecutor.

With Tawana Brawley.

Two days later, defendant Harry Crist committed suicide. Sharpton publicly charged that Mr. Pagones had murdered him to cover up his own role in the crime.

Mr. Sharpton and company once again insisted on a special prosecutor. When one was appointed, Mr. Sharpton instructed Miss Brawley not to cooperate with him, comparing the man to Hitler. One of Mr. Sharpton’s lawyers bizarrely taunted the special prosecutor, saying he was “no longer going to masturbate looking at Tawana Brawley’s picture.”

Mr. Sharpton bused in blacks from the city and led them in protests outside the courthouse. He accused New York Governor Mario Cuomo of protecting Mr. Pagones through his alleged connections to organized crime and the Ku Klux Klan. Black newspapers reported every utterance by Mr. Sharpton, Miss Brawley, and her handlers as the undisputed truth.

Perry McKinnon, a former bodyguard and chauffeur to Mr. Sharpton, gave investigators a revealing glimpse into the man behind the drama:

Sharpton acknowledged to me early on that “the Brawley story do sound like bullshit, but it don’t matter. We’re building a movement. This is the perfect issue. Because you’ve got whites on blacks. That’s an easy way to stir up all the deprived people, who would want to believe and who would believe — and all [you’ve] got to do is convince them — that all white people are bad. Then you’ve got a movement . . . . It don’t matter whether any whites did it or not . . . . If we beat this, we’ll be the biggest niggers in New York.”

The forensic rape test came back negative. On October 6, 1988, the Grand Jury released its 170-page report based on more than 6,000 pages of testimony from over 180 witnesses and at least 250 exhibits. In forceful language, the report stated that the case was a complete fabrication.

Several people had testified they saw Tawana Brawley at parties during the period she was supposedly being held and raped. Neither Miss Brawley nor her mother testified before the grand jury, although they had been subpoenaed. This is a felony, and probably explains why the two moved out of state after receiving an estimated $300,000 raised for their “defense fund.”

Unembarrassed by the grand jury decision, Mr. Sharpton barged in on Steve Pagones’ press conference announcing “Your accuser has arrived!” He continued to hound the man for several years until Mr. Pagones sued him and his team of lawyers for defamation, eventually winning combined damages of over $350,000. Mr. Sharpton refused to pay his share. In 2001, a group of wealthy black men paid off the debt for him. To this day, Mr. Sharpton publicly claims that Tawana Brawley told the truth, and claims he acted properly.

The Central Park Jogger

One morning in April 1989, a young white woman was discovered lying in a coma in Central Park in New York City and rushed to a nearby hospital. Her skull had been fractured twice; she had lost more than half her blood and was suffering from severe hypothermia. An aggressive police investigation led to the arrest of six juveniles: five black, one Hispanic. They had been part of a “wilding” gang of between 32 and 41 people who had assaulted at least eight other people the same evening. All but one formally confessed, providing “a level of detail that couldn’t have been made up.” They later retracted the confessions, claiming they had been coerced.

Mr. Sharpton called for the charges to be dismissed, claiming without evidence that the woman’s boyfriend was the guilty party. His mob of angry followers attended the trial, shouting that the victim was a whore and a liar, and claiming she had gone to the park to buy drugs. A white woman prosecutor got the same treatment. As Mr. Horowitz notes, “it was a repulsive performance even by Sharpton’s standards.”

The defendants made many self-incriminating statements during the trial, and all wound up serving at least five years in prison. The convictions were later vacated, “almost certainly illegally” in Horowitz’s estimation, and the culprits successfully sued the city for combined damages of over $40 million. Mr. Sharpton called the settlement “a monumental victory,” adding: “It is also a victory in the community that stood with them from day one and believed in their innocence. We were viciously attacked for standing with them, but we were on the right side of history.”

Yusuf Hawkins

In August 1989, a group of whites in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn shot to death a black teenager, Yusuf Hawkins. This was a case of mistaken identity; the whites were looking for a different black man who was said to be dating a neighborhood woman. Mr. Sharpton began leading illegal protest marches through the neighborhood. When three defendants out of eight were convicted in the case, the marches went on to protest the failure to convict the other five. The City Government, afraid of making a bad situation worse, refused to shut down the illegal marches. There were more than two dozen in all.

In January 1991, eight months after the verdicts, Mr. Sharpton was preparing for yet another march when he was stabbed by a local man who was furious about the marches. Mr. Sharpton’s followers showed up at the hospital where he was treated, chanting “Let’s burn down Bensonhurst. Let’s burn down New York!” Although the marches were illegal, the city eventually paid Mr. Sharpton $200,000 for its alleged failure to provide adequate protection. Soon afterwards, Mr. Sharpton disbanded the National Youth Movement and founded the National Action Network (NAN). This organization remains Mr. Sharpton’s primary power base.

Crown Heights

In August, 1991, a car driven by a Lubavitcher Jewish man jumped a curb in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn and struck and fatally injured a seven-year-old black boy. That night, rioting blacks killed a young Hasidic man in retaliation. Rioting continued for three days: 190 people were injured — mostly police officers — 27 vehicles were destroyed, seven stores were looted or burned, and 225 cases of robbery and burglary were reported.

On the second day of rioting, the father of the black child who was killed called Mr. Sharpton and asked him to be the family “advisor.” He spoke at the child’s funeral a week after the incident:

The world will tell us he was killed by accident. Yes, it was a social accident. It’s an accident for one group of people to be treated better than another. It’s an accident to allow a minority to impose their will on the majority. It’s an accident to allow an apartheid ambulance service in the middle of Crown Heights [referring to a private Hasidic ambulance service].

Blacks, Mr. Sharpton declared, “will not allow any compromise or sellouts or anything less than the prosecution of the murderers of this young man.” The driver fled to Israel.

The funeral sermon also provided an occasion for Mr. Sharpton to unbosom himself of some curious ideas about blacks:

We are the royal family on the planet. We’re the original man. We gazed into the stars and wrote astrology. We had a conversation and that became philosophy. We are the ones who created mathematics. We’re not anybody to be left to die waiting on an ambulance. We are the alpha and omega of creation itself.

Several days after the funeral, Mr. Sharpton led a crowd of 400 marchers to Lubavitcher headquarters chanting “Whose streets? Our Streets!” and “No Justice, No Peace!” One protestor carried a sign reading: “The White Man Is the Devil.”

Mr. Horowitz comments: “A second riot very easily might have broken out. . . . Al Sharpton, in a saner world, would have been arrested. But he was untouchable. He had the whole city scared.”

Freddie’s Fashion Mart

Freddie’s Fashion Mart was a successful clothing store in the heart of Harlem. It was run by a Jewish man, Fred Harari, who rented the space from a black Pentecostal Church. For 20 years he had been subletting part of the space to a black-owned record store called the Record Shack. Sometime in 1995, Mr. Harari informed the Record Shack’s owner, Sikhulu Shange, that he wanted to end the sublease so he could expand his own business. He was apparently acting on the wishes of the black church, but that didn’t matter to Al Sharpton:

Having gotten word that a black business owner was about to be evicted by a white exploiter, he swung into action. Reverend Al encouraged pickets of Freddy’s, leaving day to day logistics in the hands of a neighborhood street vendor, Morris Powell, head of NAN’s Buy Black Committee. Many black pickets wanted a sequel to the Crown Heights riot, shouting phrases such as “Jew bastards” and “blood-sucking Jews.” Powell did nothing to discourage them.

Sharpton took to the airwaves, threatening:

We will not stand by and allow them to move this brother, so that some white interloper can expand his business. And we’re asking the Buy Black Committee to go down there, and I’m going to go down there, and do what is necessary to let them know that we are not turnin’ 125th Street back over to outsiders.

Protests continued through the fall. Mr. Sharpton’s name appeared on protest leaflets calling for a boycott. On December 7, one protester forced his way into Freddie’s and shouted: “I will be back to burn the Jew store down!”

The next day, December 8, another Harlem demonstrator, a black nationalist with a long criminal history named Roland J. Smith, aka Abubunde Mulocko, walked into the store, pulled out a loaded revolver, and ordered all black customers out. Smith/Mulocko then doused several clothing bins with paint thinner, set the bins on fire and shot several people. He then turned the gun on himself. In all, eight persons, including Smith/Mulocko, died from gunshot wounds and/or smoke inhalation.

Mr. Horowitz comments:

The undeniable reality is that Sharpton was an instigator. Through his Buy Black Committee and his radio program, he escalated tensions among people eager to have their own primitive hatreds validated. To publicly threaten an “interloper” over the airwaves constituted an incitement. Incitement to riot is classified as a crime for good reason: Words and the way they are spoken, really can inflame.

It would take up too much space to recount of all Mr. Sharpton’s direct-action campaigns, the more recent of which most readers probably remember. Mr. Horowitz’s book covers them all: Amadou Diallo, the Jena Six, Don Imus, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown and the Ferguson riots, Freddie Gray and the Baltimore riots, and more. Not one of Mr. Sharpton’s campaigns has ever been justified; all have involved advocacy for criminal blacks and/or attempts to railroad innocent whites (or, at least, non-blacks).

Financial Malfeasance

Mr. Horowitz also covers Mr. Sharpton’s history of financial malfeasance. Throughout his career, he has acted as if paying taxes and other bills were optional. Charged as early as 1989 with three counts of New York State tax fraud, he accepted a plea deal: guilty to the misdemeanor charge of failing to file a tax return in 1986 in exchange for the withdrawal of two felony charges and no jail time.

The very next year he was accused of looting about $250,000 from his National Youth Movement. The New York State Attorney General’s Office called more than 80 witnesses to support 67 counts of fraud and larceny; Mr. Sharpton’s defense did not call a single witness. Nevertheless, the jury found him not guilty. As Mr. Horowitz remarks: “It’s hard to imagine even the best defense in the world getting that kind of verdict unless a number of jurors had exercised race-based nullification.”

The finances of the National Action Network have always been murky. In 1997, under pressure, Mr. Sharpton promised to make its records public only to “discover” they had been destroyed in a fire.

Mr. Sharpton’s presidential campaign of 2003-04 was loaded with fundraising practices shady enough to prompt an FBI criminal probe. Again, Mr. Sharpton claimed a fire had destroyed the records, but he was still forced to pay $285,000 in fines.

According to the New York Post, at the end of 2012, Mr. Sharpton and his organizations owed a combined total of $4.7 million in outstanding taxes and liens. His failures to pay landlords, hotels, limousine services, and other private creditors are too numerous to be listed individually. None of this can be explained by an inability to pay: Mr. Sharpton’s personal fortune is estimated at around five million dollars, and his National Action Network has recently been taking in between five and seven million dollars every year.

Running for Office

Mr. Sharpton first ran for public office in 1992, campaigning for the US Senate and calling his opponents “recycled white trash.” He finished third in a field of four. On a second try in 1994 he picked up 26 percent of the vote against incumbent Daniel Patrick Moynihan. In a campaign for Mayor of New York in 1997, he won 32 percent in the Democratic primary — almost enough to force a runoff. Still, as Mr. Horowitz writes: “During the Eighties and Nineties, any insinuation that Al Sharpton was presidential material would have provoked riotous laughter.”

But the new millennium brought much talk of a “new” Al Sharpton. He began speaking out on issues not narrowly racial, and became slightly more circumspect in his pronouncements. In May, 2001, he was arrested in Vieques, Puerto Rico for protesting Navy practice bombings. He got a 90-day jail sentence and served most of it, even going on a hunger strike.

Mr. Sharpton’s 2002 book Al on America served as his presidential campaign tract, staking out positions on a host of domestic and foreign policy issues. He formally announced his candidacy in January 2003.Mr. Horowitz writes:

Sharpton’s base wasn’t large. But being black, it was loyal. That translated into his winning about 2 percent of the votes cast in the [Democratic] primaries. Much of that support came after his formal March 15 [2004] withdrawal. He did especially well in Michigan (7 percent), New York (8 percent), South Carolina (10 percent) and the District of Columbia (20 percent).

After dropping out, Sharpton threw his support behind John Kerry, who rewarded him with a prime-time speaking slot at the party convention. Mr. Horovitz writes that:

Al Sharpton hasn’t run for president again. Then again, he’s never had to. The Rev showed he could function in the Democratic Party mainstream and maintain a statesmanlike mien. It was a mark of how far leftwards the party had moved that Sharpton’s positions were barely distinguishable from those of the other candidates. Sharpton’s image was becoming that of a sensible progressive. The party faithful no longer had to cringe at the thought of sharing a podium with him.

Sharpton and Obama

The Reverend Al lost no time preparing for 2008, inviting three Democratic candidates — frontrunner Hillary Clinton, eventual victor Barack Obama, and John Edwards — to speak at the 2007 National Action Network convention. Senator Obama told attendees: “Rev. Sharpton is a voice for the voiceless, and a voice for the dispossessed. What National Action Network has done is so important to change America, and it must be changed from the bottom up.” Although Mrs. Clinton and Mr. Edwards also fawned over him, Mr. Sharpton privately assured Mr. Obama of his support.

The Obama victory in November, 2008 raised Mr. Sharpton’s stature enormously. In March 2010, the Wall Street Journal published a story called “Obama’s New Partner: Al Sharpton,” and the following August Newsweek ran a worshipful cover story on “The Reinvention of the Reverend Al.” Such articles highlighted Sharpton’s apparent “maturation” from confrontational street protestor to pragmatist. Mr. Horowitz explains the underlying reality:

Shrewd black politicians, knowing that blacks are a minority, have come to realize that guile works better than confrontation in securing advantages, especially when one of their own happens to be head of state. Al Sharpton became a “pragmatist” because it served his interests.

In August, 2014, an unnamed White House source was quoted as saying: “There’s a trust factor with The Rev from the Oval Office on down. He gets it, and he’s got credibility that nobody else has got.” During the Ferguson riots, Mr. Obama turned to Mr. Sharpton as “both a source of information and a go-between.” Mr. Sharpton huddled with Michael Brown’s family and local leaders, then reported directly to Valerie Jarrett:

Obama was “horrified” by the images he was seeing on TV, Jarrett told Sharpton, and proceeded to pepper him with questions as she collected information for the President: How bad was the violence? Was it being fueled by outside groups — and could Sharpton do anything to talk them down? What did the Brown family want the White House to do?

Mr. Horowitz marvels: “Here was a sitting U.S. president asking Al Sharpton, a man with a long history of mass incitement to riot, to defuse a riot.”

Mr. Sharpton visited the Obama White House some 80 times, advising the administration on racial matters and on whom to pick as a successor to Attorney General Eric Holder. As president, Mr. Obama returned twice to address NAN conventions.

Anchorman

Beginning in August, 2011, and for four years thereafter, Al Sharpton served as a full-time anchorman on MSNBC’s hour-long weeknight show PoliticsNation. “The blurring of the line between reporting and advocacy,” notes Mr. Horowitz, “is a disturbing media trend of the last couple decades . . . . Yet with Sharpton, one strains to see any line.” The show’s manner of presenting the news was hardly distinguishable from what one might hear at a NAN convention. But it marked a new milestone in Mr. Sharpton’s rise to respectability. Audiences responded favorably; Mr. Sharpton attracted more viewers in his time slot than his predecessor.

In September 2015, Mr. Sharpton’s show was demoted to once-a-week on Sunday mornings, but it continues to be broadcast.

Al Sharpton Today

Mr. Sharpton has lost his White House pass, but no one should expect Pres. Trump to stand up to him. In his decades as a successful New York businessman, Donald Trump learned to treat “civil rights leaders” with kid gloves. Mr. Sharpton has refocused his energies on the legislative branch. NAN now sponsors an Legislative & Policy Conference each summer where an overwhelmingly black parade of senators, congressmen, community activists, and lawyers discuss how to “transform anger into law.” Mr. Horowitz, who has attended two of them, “can vouch for their function as a National Action Network echo chamber.”

A good illustration of just how far the Rev. Al has come was provided by the events held to mark his 60th birthday in October 2014. AT&T, Macy’s, Viacom, Walmart, and several labor unions helped him sponsor a giant two-day “education summit” for teachers and civil rights activists at New York University. This was followed by a party at the Four Seasons Restaurant in midtown Manhattan attended by New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Mayor Bill de Blasio, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, Rep. Charles Rangel, and former mayor Michael Bloomberg. Show-business celebrities who stopped by included Aretha Franklin, Spike Lee, and even Mick Jaggar, who offered this tribute to the old rabble-rouser: “The work you have done throughout your life is thoroughly admirable. Congratulations on all you have achieved.” The events put another million dollars into the coffers of the National Action Network.

Conclusion

It would be wrong to deny that Mr. Sharpton is a man of real accomplishment. As Mr. Horowitz notes:

In a contemporary context, black victimization is a difficult case to make. The denial of full rights to blacks is a decades-old relic. If crime rates are any guide, white victimization at the hands of blacks is far more common than vice-versa. And affirmative action, rechristened “diversity,” is set in stone. Blacks, legally, hold the upper hand.

In the face of this obvious reality, Al Sharpton has, for more than 30 years, worked to maintain the pretense that blacks’ overall failure is an injustice perpetrated by whites. That blacks should now be able to live at the expense of whites — whether through the political redistribution of wealth, fat jury awards (the “Ghetto Lottery”), or slavery reparations — is, in his view and that of his followers, exactly what justice requires. To reinforce this image of black victimization, he accuses the innocent, defends the criminal, treats the law with contempt, ignores facts, and rouses the basest passions of what Mr. Horowitz rightly calls his “shockingly ignorant audience.” He will never change, and at least for now there is not a single prominent figure in public life willing to stand up to him. His continuing success tells us more about our country as it does about him.