‘1917’ and the Suicide of the West

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, January 13, 2020

This review contains a few spoilers.

If you’ve seen the trailer for 1917, you know the premise: Two British soldiers must slip through enemy lines to deliver an urgent message. If they fail, the Germans will “massacre” a British unit that includes the brother of one of the soldiers. I will not summarize the plot. This film should be experienced, not explained. Its themes are visceral, not analytical.

Journalists, critics, and audiences generally like 1917, unlike the sharp divisions on Joker, Richard Jewell, and Midway. 1917 outsold the latest Star Wars film, so it’s the closest thing we now have to a universal cultural experience. There’s not a conservative or liberal interpretation of this movie.

The film is shot as if it were filmed in a single, sequential “take.” It’s a remarkable technical achievement, and you move with the characters, through the muddy trenches, pestilential bunkers, and corpse-strewn rivers. This makes it hard to beat us over the head with a clumsy political message; 1917 just shows us war.

All World War I veterans are dead, so how can we know that director Sam Mendes’ portrayal is realistic? He talked to his grandfather, a World War I veteran, and heard his stories, and we can almost hear an ancestor speaking through his blood. This is a tale — heroic and horrible — that binds families, tribes, and nations. We’re seeing an oral tradition on film. This isn’t a comic book franchise; it’s the story of a people, and it’s hard not to weep.

1917 is a classical tragedy. It’s not just that “bad things happen.” The characters face incomprehensible, almost godlike forces. Can skill or bravery save you from an artillery barrage, air attack, or incompetent officers? Yet individual choices still matter: Should you help a wounded enemy? The film is about the difference just one soldier can make. Chaos and individual choice exist together, just as they do in life.

What makes 1917 a success is its juxtapositions between beauty and horror, total isolation and sudden envelopment by masses of people. At the beginning, we are in a beautiful, peaceful field where a soldier sleeps under a tree. War doesn’t seem so bad. Yet nearby are disgusting trenches, filled with rats and grime. Just yards beyond that, there’s No Man’s Land, with its grinning skulls, torn flesh, and rotting animals. The British move into recently abandoned German trenches and it’s like traveling into the underworld. In just a few seconds, gallows humor and light banter turn into life-and-death drama.

In one scene, a soldier briefly joins a British unit that helps him get closer to his objective, but he’s forced to leave this relative safety and is attacked by a German sniper. He is knocked unconscious, the one definite break in the “one take” illusion. When he comes to, he’s in something like hell — a ruined city at night, populated by shadowy enemies, illuminated by constant flames. You can’t help but wonder if he has died and this is some cruel afterlife.

Though rooted in blood and history, 1917 resembles a dark fantasy, a waking nightmare. As another reviewer has said, we can see where Great War veteran J.R.R. Tolkien got the idea for Mordor: iron and ash, corpses and flame. In one sequence, a character walks through a ruined city square and a soldier appears. We can’t see his uniform or face. Suddenly, he charges, and we’re running. An implacable pursuer is coming to destroy you like a demon from a nightmare, and all you can do is run for your life.

In another scene, a British solider talks about the white flowers on the cherry trees back home. Later, the other protagonist is floating in a river, half-drowned. He sees white flowers, and this seems to revive him, but this moment of beauty turns into horror. He is floating, bumping into bloated, rotting corpses. Frantically he climbs out and then finds he is walking through a unit while a soldier sings the “Wayfaring Stranger.” Is he dead? He’s not sure, and neither are we.

The cast is strong, with Colin Firth, Benedict Cumberbatch, and Andrew Scott appearing in minor scenes. Game of Thrones is well represented with Dean-Charles Chapman in a lead role and Richard Madden as his older brother. All are absorbed by their characters, even if they have just a few lines. But it’s George MacKay who carries the film, shifting from cynical slacker to determined crusader to shell-shocked ruin. Ultimately, it’s his story, and we’re with him every step of the way.

It’s our story too. Naturally, the cast is overwhelmingly white. This is the war that destroyed the ancient aristocracies and empires and the faith that upheld them. After seeing our heroes wade through corpses, mud, and guts for almost two hours, we suddenly understand Surrealism, Dadaism, and the furious culture of critique that emerged after the Great War. Our leaders — European leaders — failed their peoples by leading them into this barbaric civil war.

There are some non-whites among the British forces, and this isn’t unrealistic. A Sikh is the friendliest soldier the protagonist encounters. He’s the only non-white character with a speaking part and for some reason he is with white soldiers. This is unrealistic, because Sikhs had their own units — who fought bravely. However, since the movie is about soldiers getting mixed up with different units, it’s plausible, and the Sikh is not some token “numinous Negro” Morgan Freeman who provides spiritual guidance. He’s just a normal soldier.

Interestingly, when the British travel through France, they are outraged to find that the Germans had shot the cows. The Sikh says it is “smart” because it denies food to the enemy. Is this a subtle premonition of non-white guerrilla tactics against the British Empire later in the century?

That lay in the future. During the Great War, the British called on non-whites from the Empire to fight in Europe. They called the Germans sub-human “Huns,” while postcards from the time depict “Gentlemen of India marching to chasten German hooligans.”

Even in 1917, the propaganda lingers. No Germans are portrayed positively, when we see them at all. They’re treacherous, drunk, vicious, or some combination. There was little white unity in the Great War; there’s none in this film.

In the real-life year 1917, many war supporters really believed civilization was at stake. The Germans did commit atrocities against civilians, though Allied propaganda exaggerated them. From the perspective of 2020, the political and humanitarian aims of the war seem pointless, even ridiculous. Surely, no leader would have launched the war if he could have seen even one year into the future, let alone a century.

1917 highlights a problem for white advocates. National heroes almost always made their reputation destroying other whites. 1917 awes us by showing what our ancestors endured, but it is deeply dispiriting because we know this slaughter was such a waste. Whether soldiers fought for King and Empire, democracy, or so that small nations like Belgium could be “free,” their sacrifices were not just in vain; they led to catastrophe. World War I should never have been fought. World War II would have been avoided, and whites would have secure and prosperous homelands.

Yet 1917 gives us hope. The movie ends as it begins, with a soldier resting against a tree in a peaceful field. He’s battered and exhausted but alive. The “world tree,” Yggdrasil in the Germanic tradition, unites the different realms, the underworld, the earth, and above. In 1917, Sam Mendes reaches into his ancestral past to show us European heroism. He uses modern technology to make what must be the most immersive war movie ever made. Finally, he leaves us with a hopeful message for the future. Life continues, even after horror.

The protagonist faces a moral dilemma when, hiding from the Germans in a basement, he finds a cowering French woman with a baby. He gives the baby milk and food, and is tempted to stay, but he hears church bells and knows he must continue his mission. He leaves this small family to defend his larger national family and save his fellow soldiers.

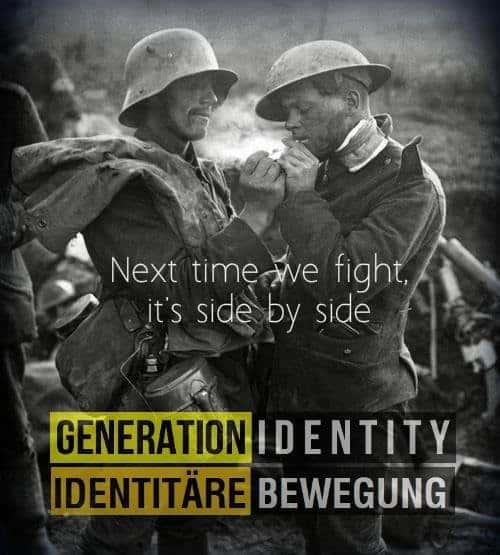

That’s our duty too. We must leave our comforts and do what we can to save our kinsmen, our families, and our future. It may mean confronting horror. It may mean physical attack. Yet duty calls us and purpose inspires us. We must do everything we can, but it must be in the service of our larger European family. Next time we fight, as Generation Identity tells us, it must be side by side.