Miscegenation

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, November 2003

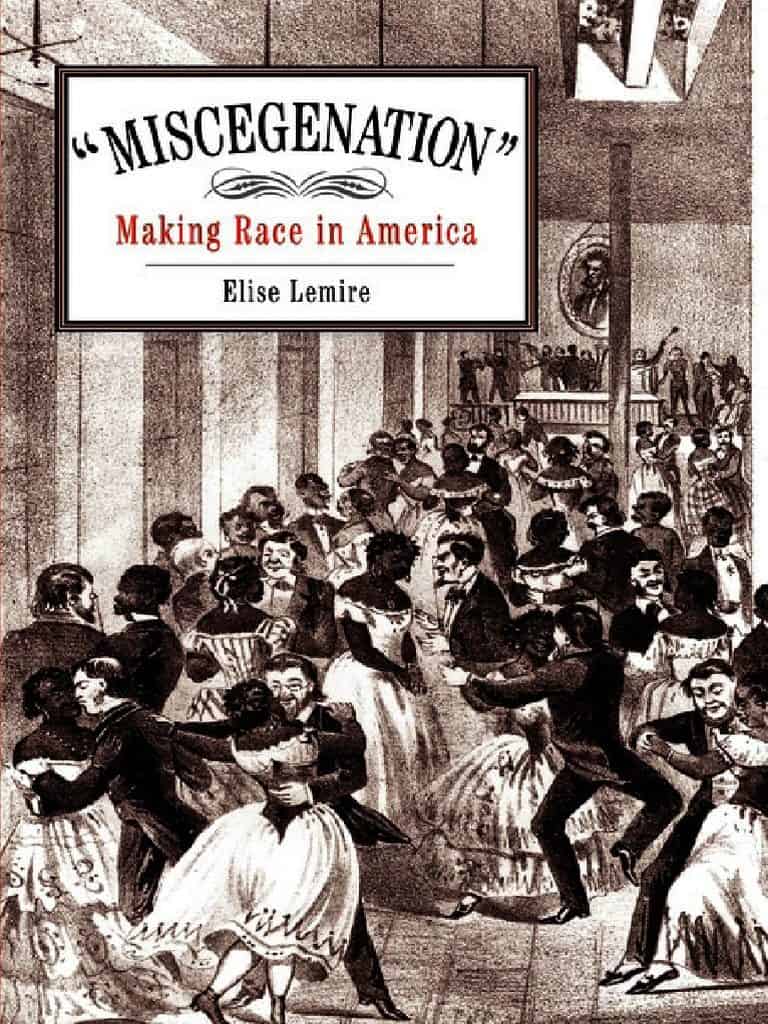

Elise Lemire, “Miscegenation:” Making Race in America, University of Pennsylvania Press 2002, 204 pp.

When “antiracist” authors write about the past, their purpose is generally to reveal the shameful bigotries of our ancestors. Southerners are their favorite targets, but Miscegenation focuses on the Northeast, and Elise Lemire, who teaches literature at Purchase College, New York, certainly succeeds in demonstrating the hostility of Northerners to race mixing in the period before the Civil War. Her larger purpose, no doubt, is to point out the wickedness of all whites — not just the already sufficiently-reviled Southern slave-owners — but her research into a little-known corner of race relations is very illuminating.

Her perspective, however, is not. Prof. Lemire, who is married to a black, is one of those silly moderns who think race is an invention: “Even though I don’t always use scare quotes in this book in my references to ‘blacks,’ ‘whites,’ and ‘inter-racial’ sex to indicate their socially constructed nature, they should always be assumed.” (Could she could bring herself to tell the police a mugger was black?) Her book jumps awkwardly from one subject to the next, but it successfully underscores the intensity and persistence of the view that interracial sex and marriage are, if not so loathsome as to as to require prescription by law, certainly a sign of depravity.

Whites have, indeed, been repelled by what they called “amalgamation.” At some point in their histories, 44 of the 50 states had laws prohibiting interracial marriage and sometimes fornication, with the first such law being passed in 1661. Prof. Lemire suggests that anti-miscegenationist feeling was stronger in the North than in the South, and she writes of the shock with which Yankees learned of close personal relations between Southern blacks and whites, and of couplings between masters and slaves.

It was Northern revulsion for such couplings that gave such a raw edge to attacks on Thomas Jefferson for allegedly siring children with his black slave Sally Hemings. This is Prof. Lemire’s first subject, and she argues that the controversy over these accusations, which reached its height during the fall of 1802 and spring of 1803, was the first widespread public discussion in America about miscegenation.

Even before these accusations, Jefferson’s political enemies were attacking him for the race-mixing potential of the all-men-are-created-equal passage from the Declaration. In July 1802, a Federalist weekly called the Port Folio, which would later have a field day with the Hemings story, published a poem put into the mouth of a fictional Jefferson slave named Quashee. It clearly suggests the subversive potential of “equality:”

Our massa Jeffeson he say,

Dat all mans free alike are born:

Den tell me, why should Quashee stay,

To tend de cow and hoe de corn?

Huzza for massa Jeffeson

And why should one hab de white wife,

And me hab only Quangeroo?

Me no see reason for me life!

No. Quashee hab de white wife too.

Huzza for massa Jeffeson.

In September of that year, a discontented office-seeker, James Callender, set off the Hemings scandal when he wrote in the Richmond Recorder: “By the wench Sally our president has had several children” (he later claimed the total was five). That same month, he described the national implications of rutting in the slave quarters:

[I]f eighty thousand white men in Virginia followed Jefferson’s example, you would have FOUR HUNDRED THOUSAND MULATTOES in addition to the present swarm. The country would no longer be habitable, till after a civil war, and a series of massacres. (Emphasis in the original.)

Back at the Port Folio, poetasters made merry with the story. The weekly published no fewer than ten verse attacks on Jefferson, some of them viciously clever. Jefferson himself had written about the odor of blacks — “[they] secrete less by the kidnies [sic], and more by the glands of the skin, which gives them a strong and disagreeable odor” — and several of the poems worked this into the attack. One purports to be the president’s own words:

When press’d by loads of state affairs

I seek to sport and dally,

The sweetest solace of my cares

Is in the lap of Sally . . .

She’s black you tell me — grant she be —

Must colour always tally?

Black is love’s proper hue for me –

And white’s the hue for Sally . . .

What though she by the glands secretes;

Must I stand shil-I shall-I?

Tuck’d up between a pair of sheets

There’s no perfume like Sally . . .

You call her slave — and pray were slaves

Made only for the galley?

Try for yourselves, ye witless knaves —

Take each to bed your Sally . . .

In another poem, Jefferson turns into a black man, the better to romp with Sally.

. . . And straight, by transformation strange,

From white to black his features change! . . .

His jaw protrudes, his lip expands,

Pah! He secretes by all the glands:

His legs inflect: his stature shrinks,

And from his skin all Congo stinks:

Behold him now, by Cupid sped,

In darkness sneak to Sally’s bed:

With philosophic nose inquire,

How rank the sable race perspire,

In foul pollution steep his life,

Insult the ashes of his wife:

All the paternal duties smother,

Give his white girls a yellow brother:

Mid loud hosannas of his knaves,

From his own loins raise a herd of slaves . . .

Another is entitled “A Philosophic Love Song to Sally,” and includes the following lines:

If down her neck no ringlets flow,

A fleece adorns her head —

If on her lips no rubies glow,

Their thickness serves instead.

Thick pouting lips! How sweet their grace!

When passion fired to kiss them!

Wide spreading over half the face,

Impossible to miss them.

The Port Folio even published a poem now thought to have been written by John Quincy Adams, which takes the form of advice to Jefferson from his friend Thomas Paine:

. . . Dear Thomas, deem it no disgrace

With slaves to mend thy breed,

Nor let the wench’s smutty face

Deter thee from the deed . . .

All the poems dwell on Hemmings’ blackness, and reflect Northern disgust at the idea of a white man embracing her. The outcry even prompted satirical prints of Jefferson as “a philosophic cock,” strutting the walk with a black hen in the background.

Jefferson Memorial (Credit Image: © Image Source/ZUMAPRESS.com)

Prof. Lemire suddenly leaves Jefferson, however, for a rambling commentary on James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, published in 1826. Her analysis consists of such things as counting the number of times the hero Hawk-eye says “I am a genuine white” or “a man without a cross [no cross-breeding]” — he reportedly does this 19 times — and arrives at the unsurprising conclusion that Cooper disapproved of interracial sex.

Considerably more interesting is Prof. Lemire’s account of anti-miscegenation activity in the North during the 1820s and 1830s. She reminds us that the easiest way to stir up opposition to abolitionists was to claim they promoted black-white marriage. Only a few avowed this publicly and many repeatedly expressed their disapproval of miscegenation, but to no avail. For many opponents, the mere fact that abolitionist meetings had mixed audiences of blacks and whites was sufficiently disgusting to make any charge believable. Only those abolitionists who firmly and publicly linked their proposals to colonization outside the United States were safe from the charge that what they really wanted was race-mixing, or amalgamation. Prof. Lemire reports that there were 165 anti-abolition riots in the North during the decade of the 1820s alone, most prompted by allegations that abolitionists were promoting inter-racial marriage.

The 1830s saw serious disturbances as well. Beginning on July 4, 1834, New York City suffered 11 days of anti-abolitionist rioting, and levels of violence not seen again until the anti-draft riots of 1863. Independence Day had traditionally been celebrated with speeches and fund raising by colonization societies, and there was some provocation in choosing it as the day for the American Anti-Slavery Society to read its Declaration of Sentiments to an audience that press accounts called “obnoxiously mixed.” Rioters broke up the meeting and attacked stores and homes owned by known abolitionists. At first, not even the militia could control the mobs, and quiet returned only after the American Anti-Slavery Society issued a statement, the first item of which was: “We entirely disclaim any desire to promote or encourage intermarriages between white and colored persons.”

Philadelphia saw a serious riot a few years later. Abolitionists had had trouble renting space to hold meetings, so in 1838 they built their own building, which they called the Pennsylvania Hall for Free Discussion. It was the biggest, most expensive structure in the city, and even before it was completed, one local paper called it the “Temple of Amalgamation,” and another “a stately edifice, sacred to the cause of amalgamation.”

Dedication ceremonies were to last three days, and to include leading abolitionists. On the evening of the second day, the well-known Angelina Grimké addressed the audience. People threw bricks through the windows and attacked several blacks as they left the building, but did not riot.

Angelina Grimké

On the third day, May 17, several thousand angry Philadelphians — many of high social standing — gathered outside the hall. The mayor was summoned, and is reported to have said: “We never call out the military here! We do not need such measures. Indeed, I would, fellow citizens, look upon you as my police! I look upon you as my police, and I trust you will abide by the laws and keep order. I now bid you farewell for the night.” After he left, the mob promptly burned the hall to the ground. Firemen arrived, but only to make sure the blaze did not spread to other buildings. After destroying the hall, the mob went to the part of town where abolitionists lived, and burned down the Friends Shelter for Colored Orphans and attacked a black church.

A police commission that investigated the riot concluded:

It can be no surprise . . . that the mass of the community, without distinction of political or religious opinions, could ill brook the erection of an edifice in this city for the encouragement of practices believed by many to be subversive of the established order of society, and even viewed by some as repugnant . . .

Prof. Lemire notes that less than a year before, a Pennsylvania constitutional convention had voted to keep the vote in the hands of white men only, arguing that “to incorporate them [blacks] with ourselves in the exercise of the right of franchise, is a violation of the law of nature, and would lead to an amalgamation in the exercise thereof.” Pennsylvania was thoroughly hostile to any measure that might lead to social or sexual relations between blacks and whites, and abolitionists often found that the only way to avoid violence was constantly to assert their opposition to miscegenation.

Prof. Lemire cites another example of white racial feeling of the period: a novel published in 1835 by Jerome Holgate (1812–1893) called A Sojourn in the City of Amalgamation in the Year of Our Lord 19 — . It is set in the future in a time when whites think it their duty to marry blacks in order to combat race prejudice. In the novel no white ever marries a black for love — that would be impossible — but out of political conviction. One of the characters even drugs his daughter and forces her to marry a black while she is unconscious.

The novel makes much of body odor. In the City of Amalgamation, all whites carry machines that neutralize the smell of blacks. If the machines break down, whites start vomiting. Many whites valiantly train themselves to endure the smell of blacks by sleeping with platters of excrement next to their beds. Prof. Lemire does not tell us how widely-read this novel was, but it was written by a Northerner for a Northern audience.

It was common in the 19th century to publish humorous prints, often with political messages. Anti-abolition and anti-amalgamation prints were common, and many referred to smells. Prof. Lemire reproduces one in which a black hypnotist called Professor Pompey sits on the lap of a white woman with his hand on her breast. She is only partially under his spell and says, “Oh, I seem to be carried away into a dark wood where I inhale a perfume much like that of a skunk.” Another black standing nearby says, “Take care dar ‘fessor Pompey! I hab some notion arter dat young white Lady, myself.”

By the end of the 1830s, prints of interracial couples flirting and kissing were a common form of anti-abolition propaganda designed to stir up disgust for racial mixing. Even children’s books sometimes conveyed this message, as in the print reproduced on the previous page from the Boys Book of Fun.

Newspapers of the period reflected the same views. In a July 7, 1843 account of a mixed-race abolitionist meeting, the New York Times wrote, “There was a full and fragrant congregation . . .” Of the same meeting, the Morning Courier and New-York Inquirer reported that a hymn “was chaunted with great fervour as well as fragrancy by the Mesdames of the ladies of colours.” In an editorial the same year, the New-York Commercial Advertiser made a more general statement: “[The Creator] endowed his creatures with the faculty of TASTE, accompanying it with entire freedom of choice, thereby forming a perpetual and insurmountable barrier to the execrable amalgamation.” (Emphasis in original.)

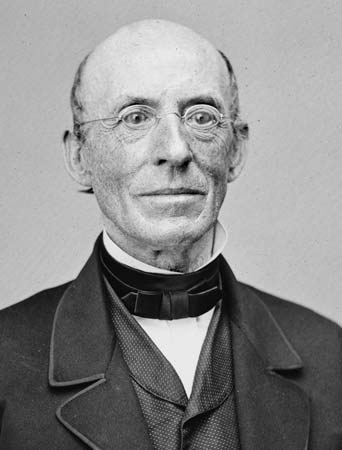

Prof. Lemire points out that this was nevertheless a period during which there was considerable agitation to overturn the 1705 Massachusetts law banning inter-racial marriage. On Jan. 1, 1831, in the inaugural issue of the Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison made the first public call to abolish the ban. Proponents of colonization promptly accused Garrison of wanting to marry a black, though no abolitionist is known to have done so before the Civil War.

William Lloyd Garrison, editor of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator.

Prof. Lemire notes that the Massachusetts movement against the ban was libertarian rather than pro-black; its proponents made no secret of their distaste for miscegenation, but believed people had a right to make bad choices. John P. Bigelow, the primary lobbyist, called marriage to a black “the gratification of a depraved taste,” and the official text accompanying the new 1843 law stated, “It is cruel, unjust and improper to . . . punish that as a high crime, which is at most evidence of vicious feeling, bad taste, and personal degradation.” Prof. Lemire writes that it was possible to change the law, only because even proponents of the change believed good taste would keep the races apart. This conviction arose, in part, because abolitionists had been forced so frequently to forswear “amalgamation” that by the 1840s the public began to believe them.

Later, a few abolitionists did openly promote miscegenation. In 1863, Louisa May Alcott, best known for her children’s book Little Women, published a short story called “M.L.” in the anti-slavery magazine, Commonwealth, in which a white woman marries a black man. Some of the force of her story is lost, however, in that the “black” is the son of a quadroon and passes for white. The heroine learns of his Negro ancestry only after falling in love with him. Some abolitionists did go considerably further, however. In the same year, abolitionist Wendell Phillips wrote of “that sublime mingling of races which is God’s own method of civilizing and elevating the world.”

Ironically, the most widely read pro-race-mixing document of the period was an anti-miscegenist hoax! Late in 1863, two Democrats who opposed Lincoln’s reelection published a 72-page pamphlet called Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races, Applied to the American White Man and Negro. The two anonymous authors were New York City journalists pretending to be Republican supporters of the president. Lincoln had just issued the Emancipation Proclamation, and they wanted to promote the idea that Republican and abolitionist policies led directly to race mixing, for which they proposed the term “miscegenation.” They argued that amalgamation was an inappropriate, metallurgical term, whereas a new coinage from the Latin (miscere — to mix, and genus — race) “would express the idea with which we are dealing.”

The pamphlet had chapter titles like “The Blending of Diverse Bloods Essential to American Progress,” and insisted that “[a]ll that is needed to make us the finest race on earth is to engraft upon our stock the negro element which providence has placed by our side on this continent.” In “Miscegenation in the Presidential Contest,” they proclaimed that a vote for Lincoln was a vote for miscegenation. “When the President proclaimed Emancipation he proclaimed also the mingling of the races,” argued the pamphlet. “The one follows the other as surely as noonday follows sunrise.” For those with reservations about this happy consummation the authors provided a chapter called “Miscegenetic Ideal of Beauty in Women,” in which they argued that ideals of beauty were arbitrary and that fair-minded whites should find blacks beautiful.

The pamphlet was wildly popular among Democrats, who trumpeted it as a revelation of what the dastardly Republicans really wanted. The new word caught on immediately, and Democrats were soon referring to Lincoln’s proclamation as the “Miscegenation Proclamation.”

In its discussion of the pamphlet, the New York Times took deep offense at the idea that whites should be encouraged to find blacks beautiful. It complained that in the midst of a “gigantic war,” people should not be writing “all about the possibility of the whites of this continent losing their admiration for their own women, repudiating the standard of beauty furnished them by natural instinct, and intermarrying with Negroes.” The Times went on to print a satirical story about whites reduced to going through neighborhoods with tracts and plaster casts, trying to demonstrate the superior beauty of whites in order to keep them from marrying blacks.

Abolitionists were taken in by the hoax just like everyone else, and some of the wilder ones applauded it wholeheartedly. Angelina Grimké wrote to the authors telling them that she and her sister Sarah were “wholly at one” with the arguments in the pamphlet. However, she raised a question of tactics: “[W]ill not the subject of amalgamation so detestable to many minds, if now so prominently advocated, have a tendency to retard the preparatory work of justice and equality which is so silently, but surely, opening the way for a full recognition of fraternity and miscegenation?” Miscegenation was great stuff, but talking about it openly might scare people.

Parker Pillsbury, editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard (official journal of the American Anti-Slavery Society) wrote to the authors that their pamphlet had “cheered and gladdened a winter morning.” His paper printed a glowing review of the book, agreeing with the authors that “there will be progressive intermingling and that the nation will be benefited by it.”

A number of political cartoons appeared, capitalizing on the popularity of Miscegenation. One, printed in 1864, was called “Miscegenation or the Millennium of Abolitionism.” In it, a black woman named Dinah Arabella Aranintha Squash is being presented to Abraham Lincoln who replies, “I shall be proud to number among my intimate friends any member of the Squash family, especially the little Squashes.” Since Miss Squash, in her words, likes to “gallevant ‘round wid the white gemmen” and enjoys “de hebenly Miscegenation times,” the little Squashes are likely to be mulattos. In the same cartoon, a black man pleads to a white woman: “Lubly Julia Anna, name de day when Brodder Beecher [Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, former editor of the abolitionist Independent] shall make us one.” She replies, “Oh! You dear creatures. I am so agitated! Go and ask Pa.” Another print called The Miscegenation Ball depicts black and white couples dancing together and sitting on couches groping each other.

Shortly after Lincoln won reelection, the authors of the pamphlet laid open claim to it, and their triumph inspired imitators. Democrats circulated a “Black Republican Prayer,” in which a Negro asks God to make “the blessings of Emancipation extend throughout our unhappy lands and the illustrious sweet-scented Sambo nestle in the bosom of every Abolition woman . . . Amen.”

Another Democrat posing as a Republican wrote the 1864 pamphlet reproduced on the previous page. Of the illustration on the cover, “L. Seaman” wrote:

“The different shades of complexion of the two contrast . . . beautifully and lend . . . enchantment to the scene . . . [T]he sweet, delicate little Roman nose of the one does not detract from the beauty of the broad, flat nose, with expanded nostrils, of the other — while the intellectual, bold majestic forehead of the one forms an unique though beautiful contrast to the round, flat head, resembling a huge gutter mop, of the other.” Probably even Angelina Grimké would have realized this was satire.

Prof. Lemire ends her book with the obligatory assertion that race is a mirage: “The idea that there is a special kind of sex that is ‘inter-racial’ is just as much a racist social fiction as the idea there is something namable as ‘miscegenation.’” But what power this “social fiction” seems to have!

Prof. Lemire does not appear to think it necessary ever to explain to readers why it was wrong for generations of Americans to oppose miscegenation. No doubt, in her circle, it is impossible even to imagine anything so retrograde. Fortunately, healthy preferences persist despite race-mixing propaganda. As recently as 1991, 66 percent of whites were prepared to tell a pollster they would disapprove if a close relative married a black. Probably even more would disapprove, but were afraid to say so.

Interesting and heretical sentiments come to light in the privacy of the voting booth. Like many states, South Carolina and Alabama wrote prohibitions of miscegenation into their constitutions. After the Supreme Court decision of 1967, these bans were unenforceable, but the language remained. In 1988 and 2000 respectively, voters in the two states went to the polls, in accordance with the procedures required to amend the state constitutions. Substantial minorities in both states voted to keep the ban: 38 percent in South Carolina and 41 percent in Alabama. Five of 47 South Carolina counties voted to keep the ban, as did no fewer than 23 of 67 counties in Alabama. There was no racial breakdown of the vote, but it may be that close to half the white electorate may have opposed rescinding the ban. As it so often does, published opinion and “respectable” discourse completely ignore the convictions of many millions of Americans.

It was, of course, opposition to miscegenation that was at the heart of centuries of law, custom, and sentiment that kept the races apart. The races cannot now avoid contact, but where it matters most, whites have not entirely forsaken the wisdom of their ancestors.