A Ruthless Mexican Drug Lord’s Empire is Devastating Families With Its Grip on Small-Town USA

Beth Warren, Louisville Courier Journal, November 25, 2019

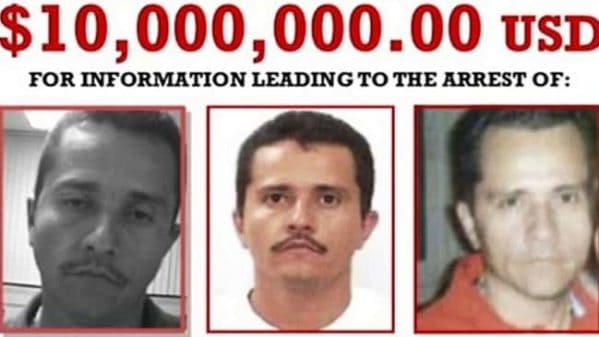

Nemesio Oseguera-Cervantes, AKA, “El Mencho”

Somewhere deep in Mexico’s remote wilderness, the world’s most dangerous and wanted drug lord is hiding. If someone you love dies from an overdose tonight, he may very well be to blame.

He’s called “El Mencho.”

And though few Americans know his name, authorities promise they soon will.

Rubén “Nemesio” Oseguera Cervantes is the leader of Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación, better known as CJNG. With a $10 million reward on his head, he’s on the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s Most Wanted list.

El Mencho’s powerful international syndicate is flooding the U.S. with thousands of kilos of methamphetamines, heroin, cocaine and fentanyl every year — despite being targeted repeatedly by undercover stings, busts and lengthy investigations.

The unending stream of narcotics has contributed to this country’s unprecedented addiction crisis, devastating families and killing more than 300,000 people since 2013.

CJNG’s rapid rise heralds the latest chapter in a generations-old drug war in which Mexican cartels are battling to supply Americans’ insatiable demand for narcotics.

A nine-month Courier Journal investigation reveals how CJNG’s reach has spread across the U.S. in the past five years, overwhelming cities and small towns with massive amounts of drugs.

The investigation documented CJNG operations in at least 35 states and Puerto Rico, a sticky web that has snared struggling business owners, thousands of drug users and Mexican immigrants terrified to challenge cartel orders.

It also identified at least two dozen “cells,” which the DEA defines as places where cartel members set up shop to do business and live in the communities.

The unparalleled speed of CJNG’s growth coast to coast in less than a decade has made the cartel a “clear, present and growing danger,” says Uttam Dhillon, DEA’s acting administrator.

The billion-dollar criminal organization has a large and disciplined army, control of extensive drug routes throughout the U.S., sophisticated money-laundering techniques and an elaborate digital terror campaign, federal drug agents say.

Its extreme savagery in Mexico includes beheadings, public hangings, acid baths, even cannibalism. The cartel circulates these images of torture and execution on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and other social media sites to spread fear and intimidation.

In Mexico, El Mencho is a household name.

But in America, few know who he is or why his rise to power matters.

Brenda and Karl Cooley of Louisville certainly didn’t know his name when their son Adam overdosed on fentanyl in March 2017. Adam died midsentence while writing a thank-you note to a friend on the eve of entering a rehab facility.

Who was to blame? his anguished parents asked.

“They’re killing the next generation, and one of them was my son,” Brenda Cooley said.

Courier Journal reporters pieced together CJNG’s network, from the suburbs of Seattle, the beaches of Mississippi and South Carolina, California’s coastline, the mountains of Virginia, small farming towns in Iowa and Nebraska, and across the Bluegrass State, including in Louisville, Lexington and Paducah.

A cartel member even worked at Kentucky’s famed Calumet Farm, home to eight Kentucky Derby and three Triple Crown winners.

Ciro Macias Martinez led a double life, working as a horse groomer by day and overseeing the flow of $30 million worth of drugs into Kentucky by night before being imprisoned in 2018 for meth trafficking and money laundering, federal records show.

El Mencho’s drug empire “is putting poison on the streets of the U.S.,” said Chris Evans, who runs the DEA’s day-to-day global operations.

CJNG has skirted Mexican and U.S. inspections at legal border crossings by hiding drugs in semitrailers hauling tomatoes, avocados and other produce, dumping at least 5 tons of cocaine and 5 tons of meth into this country every month, according to DEA estimates.

It shows no signs of slowing down.

{snip}

While officials can’t say how much of the U.S. drug trade comes from CJNG, they predict the powerful organization is poised to supplant the more well-known and established Sinaloa Cartel as the world’s most powerful drug trafficking organization.

CJNG’s increased distribution of fentanyl across the country has helped the synthetic opioid unseat heroin as the nation’s No. 1 killer.

The Courier Journal could not say with certainty who supplied the drugs that killed Adam Cooley. But federal agents say CJNG was Kentucky’s main supplier of fentanyl at the time of his death.

Throughout 2019, reporters analyzed thousands of court records of more than 100 criminal drug cases around the country and talked to more than 150 federal drug agents, police officers, defense attorneys and prosecutors.

{snip}

The investigation documented how in each new community, CJNG uses local traffickers who can blend in to sell their drugs, with no regard for their race or ethnicity.

“If it’s coming from a cartel, they could have sold a pound to Asians, black guys, outlaw motorcycle gangs, white trash,” said Lt. Jeremy Williams, of the Ashe County Sheriff’s Office in North Carolina. His testimony helped convict a trafficker connected to CJNG in 2014.

{snip}

El Mencho and his cartel, with more than 5,000 members worldwide, have a clear-cut objective:

“They want to control the entire drug market,” said Matthew Donahue, who oversees foreign operations for the DEA.

“If that takes them killing other cartels or killing innocent people, they will do it.”

{snip}

The Courier Journal’s investigation documented cells where CJNG members moved in, settling into a luxury condo near downtown Nashville’s honky-tonk district; an upscale Hollywood high-rise apartment near Sunset Boulevard; and sidewalk-lined suburbs in Cairo, Illinois; Johnson City, Tennessee; and Kansas City, Missouri.

CJNG even established a cell in south-central Virginia, buying or renting a cluster of modest homes in Axton — an unincorporated community of roughly 6,500.

In Mexico, a DEA investigator said he was stunned when he learned CJNG cells were popping up in communities as small as Axton.

“What are they doing way out in the middle of nowhere?” he asked his team.

Hearing more details, the investigator, who asked not to be identified to protect his work, acknowledged to The Courier Journal: “It’s a great strategy.”

{snip}

Smaller towns. Smaller police forces. More unchecked opportunities.

“Big cities have big police departments and DEA, FBI and (Homeland Security Investigations) and an ability to look at intelligence and focus on their cells and contacts,” said the DEA’s Donahue.

“But it’s a little different when you go to Boise, Idaho, and other small towns where they don’t have the resources to really focus on an international cartel.”

{snip}

In mid-October, 13 Mexican police officers were killed in an ambush in El Mencho’s home state of Michoacán in western Mexico. Attackers in armored vehicles opened fire with high-caliber weapons, gunning down officers driving five SUVs.

CJNG took credit on social media for the massacre.

{snip}

For 53-year-old El Mencho, success did not come early. He dropped out of sixth grade to help his family pick avocados.

The teenager sneaked into the U.S. and tried to build a customer base as a street-level dealer. But he kept getting caught.

As a young adult, he and his older brother, Abraham Oseguera Cervantes, sold heroin to two undercover police officers at a San Francisco bar in 1992 and were sent to federal prison on drug trafficking charges.

El Mencho was deported in 1997 and then traveled to Tijuana. There, he built a thriving drug trafficking business, but the city’s dominant cartel ordered him to leave when leaders became threatened by his success.

He briefly worked as a police officer in Tomatlán, a small town in Jalisco, learning the inner workings of law enforcement, said DEA Special Agent Kyle Mori, who is heading the U.S. criminal investigation against El Mencho from Los Angeles.

El Mencho eventually joined the Milenio Cartel, gaining a reputation as a cunning sicario, or hitman, and then a boss of hitmen in Guadalajara, Jalisco’s capital city.

Passed over for promotion, El Mencho teamed with his in-laws who ran an affiliated cartel and forged his own criminal organization in early 2011 — CJNG.

He quickly amassed a private army, with CJNG members recruiting or kidnapping hundreds of men in their 20s and boys as young as 12. The DEA’s Donahue said many were taken to remote paramilitary camps where they were trained as assassins.

Those who tried to run were tortured, killed and sometimes cannibalized by fellow recruits in what U.S. federal agents describe as a disturbing rite of passage.

His followers have spread to nearly all of Mexico’s 32 states, including the cities of Guadalajara and Tijuana, both crucial to moving drugs into the U.S.

{snip}

In 2015, El Mencho flexed that power to strike back at law enforcement who tried to stop him.

Tipped off that a police caravan was on its way to grab El Mencho, CJNG hitmen hid along the route in April 2015 and ambushed four police vehicles. Cartel members fired hundreds of rounds and hurled grenades and jugs of gasoline.

Fifteen officers died.

A month later, Mexican authorities learned of El Mencho’s new hiding spot and organized a secret mission to capture him.

Federal police officer Ivan Morales, his partner and soldiers with the Mexican national defense climbed aboard helicopters and headed toward a CJNG compound in the Jalisco mountains.

As they hovered over a cartel convoy, CJNG members fired Russian-made rocket-propelled grenade launchers, shooting down Morales’ helicopter into a cluster of trees.

{snip}

Just hours after the crash, the cartel carried out coordinated attacks in 39 cities, blowing up banks, gas stations and setting cars and semis on fire on major highways to slow down police reinforcements.

“When they shot the helicopter out of the sky is when everyone respected CJNG as a powerhouse cartel and a rival of Sinaloa,” Donahue said.

{snip}

Adults and children are forced to work in CJNG’s crude meth super labs — vats on patches of dirt hidden in the jungle. Entire families who resist have been slaughtered, Donahue said.

The cartel also recruits spies in the Mexican government and police to keep its leaders out of jail and avoid drug busts. Those who refuse bribes are threatened or killed.

A veteran Jalisco police officer, who asked not to be identified for his safety, said CJNG has officials on its payroll at the local, state and federal levels. The information leaks make catching El Mencho extremely difficult, he said.

He shares intel with the DEA, but not his own people.

{snip}

“The threat of Mexican cartel violence and the drugs they bring into our nation can’t be overstated,” said Russell Coleman, the top federal prosecutor for the Western District of Kentucky. His office has prosecuted Sinaloa and CJNG members.

Yet, no sooner had authorities busted Kentucky’s CJNG ring than the cartel replaced Macias, sending in another team. It hauled in more than 3 kilos of fentanyl, the synthetic opioid so potent that an amount as small as Abraham Lincoln’s cheek on a penny can be fatal.

{snip}

Pointing to more than 70,000 Americans who overdosed and died in 2017, Coleman said, “We’re fighting a war for our families, and (the cartels) are winning.”

{snip}

In a Chicago money-laundering case, a Guadalajara businessman working with CJNG urged an informant to settle his drug debt quickly, describing how cartel members settled another man’s debt: “They chopped off his fingers.”

And federal prosecutors alleged in court that convicted drug trafficker Jesus Enrique Palomera, the leader of a cartel cell in Tacoma, Washington, ordered the kidnapping and murder of a man whose fingers and toes were chopped off — a common method of torture in Mexico.

{snip}

Beginning in 2015, the U.S. Treasury Department designated El Mencho a “kingpin,” along with his brother-in-law, Abigail González Valencia, leader of the Los Cuinis cartel.

That designation allowed the department to levy sanctions against Mexican businesses linked to the cartels, including a sushi restaurant, a tequila business, shopping centers, a medical clinic, two newspapers and famed Hotelito Desconocido, visited by Hollywood stars.

The strategy: Make it illegal for any U.S. citizen or company to spend money at a cartel-affiliated business. It also forbids any U.S. bank to approve loans or credit card transactions for those CJNG-backed enterprises.

{snip}

Mexican marines almost captured El Mencho in October 2018. They stormed a hideout west of Guadalajara, but the cartel leader climbed into a vehicle and was rushed to safety.

After his escape, the U.S. took its manhunt public.

On Oct. 16, 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions, standing next to a large “Wanted” poster of El Mencho, announced a $10 million reward for his capture and unveiled detailed indictments against him and CJNG.

Treasury Department officials stood with Sessions and announced more sanctions on businesses linked to CJNG and its affiliate, Los Cuinis. More than 60 were targeted, including a biotech consulting company, a bakery and hillside vacation cabins.

“We consider this cartel to be one of the five most dangerous transnational criminal organizations on the face of the Earth, and it is doing unimaginable damage to the people of this nation,” Sessions said.

{snip}

On the run and out of sight, El Mencho is described by some veteran agents as a ghost. From the shadows, he continues to lead CJNG with ruthless authority.

{snip}

Even if U.S. and Mexican investigators can track El Mencho’s location, capturing him won’t be easy.

Agents say he typically travels in a convoy, surrounding himself with dozens of well-trained mercenaries armed with military-grade weapons that can tear through tanks, even aircraft.

{snip}

Moreover, the U.S. lacks the authority to make arrests in foreign countries, said Evans, a senior DEA official.

“If an agent saw him, we couldn’t say, ‘Hey, we’re gonna grab El Mencho right now, take him and put him into custody.’ We’re guests in their country.”

But DEA agents across the border are sharing intelligence and working with their Mexican counterparts to devise ways to dismantle CJNG and arrest its leaders.

They’re also working to train Mexican police to improve the country’s “solve rate” for kidnappings and murders, which is less than 5%. Many are committed by cartels.

{snip}

The U.S government has crippled dozens of businesses that supported CJNG and sent El Mencho’s son and chief financial backer to prison, along with members of his inner circle.

Still, El Mencho’s empire is growing.

“It was almost unbelievable, the things we were hearing, the amount of drugs,” said Benjamin Taylor, who oversees investigations for Homeland Security in Gulfport, Mississippi.

{snip}

Make no mistake, Taylor said. CJNG is “among us.”

“That’s kind of hard to believe, but it’s true.”