Do Whites Need an Ethnostate?

Thomas Jackson, American Renaissance, October 1994

The Racial Compact, Richard McCulloch, Towncourt Enterprises 1994, 135 pp.

Seldom are the long-term prospects for the white race considered honestly and dispassionately. To do so requires keenness of vision and a willingness to pursue ideas even to their most unpleasant conclusions. In The Racial Compact, Richard McCulloch calmly describes the choices we face: establish a new, moral form of racial consciousness or become extinct.

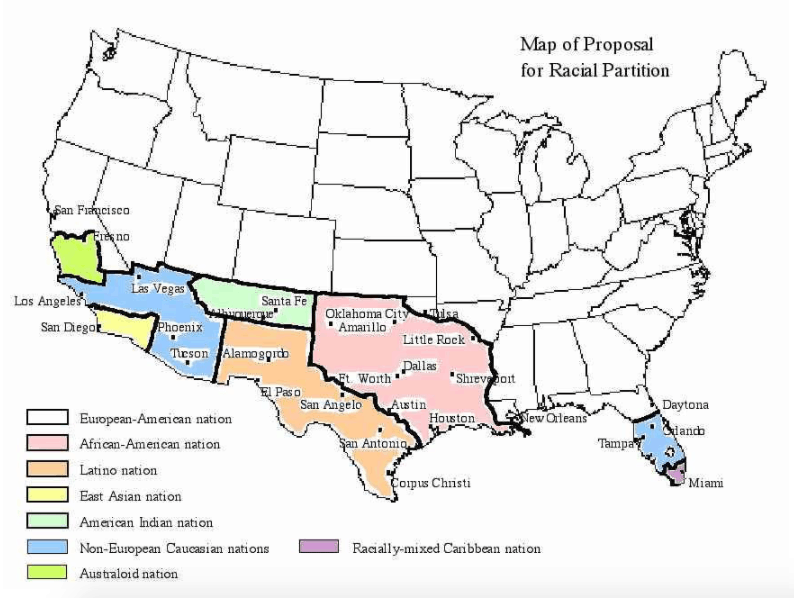

Richard McCulloch’s proposed racial partition of the United States. From his book, “The Racial Compact.”

To begin with, Mr. McCulloch reminds us that reproductive isolation was the single necessary condition for the development of racial diversity. It was only because they lived in separate, isolated groups that humans diverged into races and sub-races. If these groups had remained separated, they would have evolved into different species, but this process was arrested by migration and intermixture.

The last century or so has brought an unprecedented rise in intermixture, thanks to advances in transportation. The end of geographic separation has created multi-racial societies that are now celebrated, at least in formerly-white countries, as good and inevitable.

As Mr. McCulloch points out, even though multi-racialism is touted as an affirmation of diversity, it destroys racial diversity, and does so in two ways. One is interbreeding. Most people choose mates of the same race, but those who do not will have children who have lost the unique features of their parents’ races.

If it were widely practiced, interbreeding could obliterate racial distinctions in just a few generations. The most vulnerable races are those whose traits — like the fair hair and light eyes of whites — are genetically recessive. Consistent interbreeding could eventually produce a nearly uniform mass of humanity.

At the same time, even if there were no interbreeding, multi-racialism would eventually abolish diversity through simple displacement. Mr. McCulloch reminds us of Gause’s Law of Exclusion, according to which different groups of animals that have the same physical requirements cannot coexist for any length of time in the same habitat. “All but one,” explains Mr. McCulloch, “eventually become extinct.”

There is no doubt as to which race, under present multi-racial circumstances, would become extinct. Whites (or “the Nordish,” as Mr. McCulloch calls them, to distinguish northern Europeans from Turks, Arabs, and others who are often called “white”) are already only a ten percent minority of the world population and account for only five percent of the world’s births. Even in their traditional European homeland they are being displaced by migrants from less successful societies. Mr. McCulloch draws the only possible conclusion:

If their commitment to multiracialism . . . remains unchanged, and recent demographic trends in immigration, differential birthrates and racial intermixture continue, one can project that by the year 2100 the remnants of the native Nordish populations of northwest Europe will be too small to constitute a viable continuation of their previous existence. They will be effectively extinct.

In North America, where intermixture and displacement are further advanced than in Europe, effective extinction could come even sooner.

What has put these gruesome trends in motion, and what can be done about them? Clearly, the multi-racialism that portends extinction for whites has been permitted and even encouraged by them. Mr. McCulloch quotes a statement made by the Dutch Minister of Education and Science in 1989:

I think that the Dutch will in the long run disappear. The [immigrant] ethnic groups’ population growth is much faster [%-2]than that of the Dutch . . . [%0] . The white race will in the long term become extinct. I don’t regard this as positive or negative. Apparently we are happy with this development.

This statement is unusual only because a government official has logically (and cheerfully) described the long-term consequences of current policies. Most proponents of multi-racialism would never admit that government policies will lead whites to extinction; most would probably not admit it to themselves.

For those who do see the future clearly, and who do not cheerfully accept the prospect of extinction, Mr. McCulloch proposes only one solution: peaceful separation. Reproductive isolation was what gave rise to different races, and only reproductive isolation can preserve them. In order to restore the conditions for their survival, whites must repatriate recent, non-white immigrants from Europe and divide North America along racial lines.

Of course, to most Americans, this is a shocking proposal. It does not matter that Mr. McCulloch’s logic is airtight; racial separation is, to them, unthinkable. Why, though, do the majority of whites submit to policies that can only lead to their own disappearance? Why is the only guarantee against extinction unthinkable?

Intellectual Straight Jacket

Some of Mr. McCulloch’s most interesting observations are about the intellectual straight jacket that prevents whites from acting in their own interests. A large part of the problem is the widely accepted view that racial consciousness, at least among whites, can only be an expression of hatred and the desire for domination. Mr. McCulloch calls this kind of racial consciousness — of which there has been plenty — “immoral racism.” In its place, he proposes “moral racism,” which is not just an expression of love for one’s own race but a recognition of the rights of all races. It is on the basis of moral racism that he proposes what he calls The Racial Compact, that is, the mutual recognition of the rights of races and acceptance of the peaceful separation this would require.

For moral racism to win broad support, it must not depend on ideas of racial inferiority or superiority but on recognition of the importance of preserving all races. Racists will always be loyal to their own races, but this should never prevent them from securing the same racial rights for others that they demand for themselves.

Mr. McCulloch points out that most people have never heard of moral racism and this is a great obstacle to its acceptance. The idea that races could separate, wish each other well, and pursue their unique destinies is one that is never publicly articulated. However, if the white race is to have a future — and in the very long term, if any race is to have a future — some form of racial compact must be established. Steeped as they are in the idea that expressions of racial pride are immoral, most people have no concept of an ethic of racial preservation and mutual respect.

Mr. McCulloch draws a parallel between racial rights and individual rights. Everyone knows that there are good and bad kinds of individualism. The bad kind is non-reciprocal and exploitative, but that does not mean all affirmations of the individual are exploitative. The same is true for race. Expressions of racial consciousness can be spiteful and even murderous. Most whites have been trapped into thinking that this must always be so, and Mr. McCulloch argues that this is because it so often has been so. No peoples have ever achieved peaceful racial separation under conditions of mutual respect and fairness, so it is not surprising that scarcely anyone thinks of it as a solution to racial problems.

Another reason many people are unwilling to exert themselves to avoid extinction — even if they understand that this is where multi-racialism leads — is that they do not care. Mr. McCulloch calls this “nihilism by default.” “[A] simple lack of interest, care and concern, often not consciously intended” he writes, “is by far the most common form [of anti-racial thinking], and also the most insidious.”

Part of the problem is that today’s popular culture emphasizes the individual and the present while ignoring the future and the group. Many white Americans are dimly aware that current policies are reducing their race to a minority and that this is likely to be awful. That, however, will be a problem for other generations. The present is tolerable, so why worry?

Mr. McCulloch also points out that economics leaves no room for race. It is more efficient to treat all people as interchangeable parts in the world economy. Since the preservation of races has no monetary value, cheap foreign workers are a costless boost to the New-World-Order GNP.

Whites v. Spotted Owls

Here Mr. McCulloch draws an arresting parallel between racial preservation and environmentalism. At one time people treated the environment as if it were costless and expendable. Now, powerful movements have sprung up to save the habitats of every possible obscure fish or bird, even if humans must pay a high price to do so. Human races, particularly the white race, are like the environment. If we proceed heedlessly, if we are oblivious to their fates, they will be destroyed. Only the most unbalanced mind can work fanatically to save the spotted owl but be oblivious to the possible disappearance of whites.

For whites themselves, their own preservation is the most natural, normal, and healthy goal they could have. Human races are not merely interesting biological phenomena, though they certainly deserve as much protection on those grounds as the snail darter; they are the bearers of magnificent cultures and traditions that cannot survive without the people who created them. Individual lives are short, but the race and culture are potentially immortal. The death of a race is an infinitely, immeasurably greater loss than the death of any individual.

Mr. McCulloch is surely right to argue that in a time when racism is so widely condemned, the only racism that can win enough advocates to bring about the establishment of The Racial Compact is a new racism, free of the taint of hatred and exploitation. Whites have been so terrorized by a one-sided, closed-minded depiction of racism that most are prepared to let their people and culture disappear rather than be guilty of it.

In Mr. McCulloch’s view, promoting a new and moral racism is the most urgent task facing white civilization. This book is an important contribution to that task.