The West and What Comes After

Ross Douthat, New York Times, July 8, 2017

While Donald Trump was giving a speech in Poland last week depicting a West whose values, heritage and freedoms are threatened by the weakening of borders and a loss of confidence within, I was reading about the last days when European empires ruled the globe.

Those years, the years of decolonization that followed World War II, are the subject of a book by the anthropologist and historian Gary Wilder, “Freedom Time: Negritude, Decolonization and the Future of the World.” Wilder follows two black intellectuals and politicians, Aimé Césaire of Martinique and Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal.

Léopold Sédar Senghor

{snip}

They were Western-educated Francophones who read deeply in the European canon, who believed in the “miracle of Greek civilization.”

{snip}

At the same time, they argued for their own race’s civilizational genius, for a negritude that turned a derogatory label into a celebration of African cultural distinctiveness.

And finally they believed that part of the West’s tradition, the universalist ideals they associated with French republicanism and Marxism, could be used to create a political canopy — a transnational union — beneath which humanity could be (to quote Césaire) “more than ever united and diverse, multiple and harmonious.”

{snip}

Yesterday’s African nationalists argued, reasonably, that you cannot develop an African civilization if your center of political authority is still in Europe.

Today’s Western nationalists argue, also plausibly, that many European distinctives are unlikely to survive if nation-states are weak, mass immigration constant, Christianity and Judaism replaced by indifferentism and Islam.

{snip}

It’s a view I endorse. But in the European case I don’t necessarily believe that it will prevail.

{snip}

Nor do I have much confidence that the present burst of European nationalism is more than a spasm, a reflex — not when religious practice is so weak, patriotism so attenuated, the continent’s birthrate so staggeringly low.

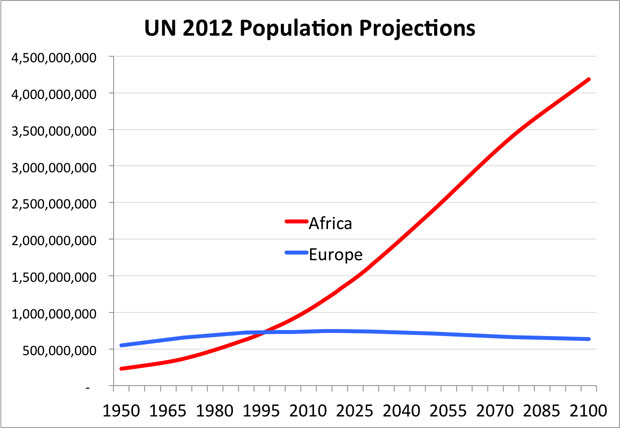

What’s more, I can read the population projections for Europe versus the Middle East and Africa, which make ideas like “managed migration” and “careful cultural exchange” seem like pretty conceits that 21st-century realities will eventually explode.

Which brings me back to Césaire and Senghor, men who loved their African heritage and yet also knew European civilization better than most educated Europeans do today. Their fantasy of a post-imperial union between north and south, white and black, was in their times just that.

But as a striking sort of African-European hybrid, as prophets of a world where the colonized and the colonizers had no choice but to find a way to live together, the West’s future may belong to them in some altogether unexpected way.