Prisoner of Democracy

John Tyndall, American Renaissance, April 1993

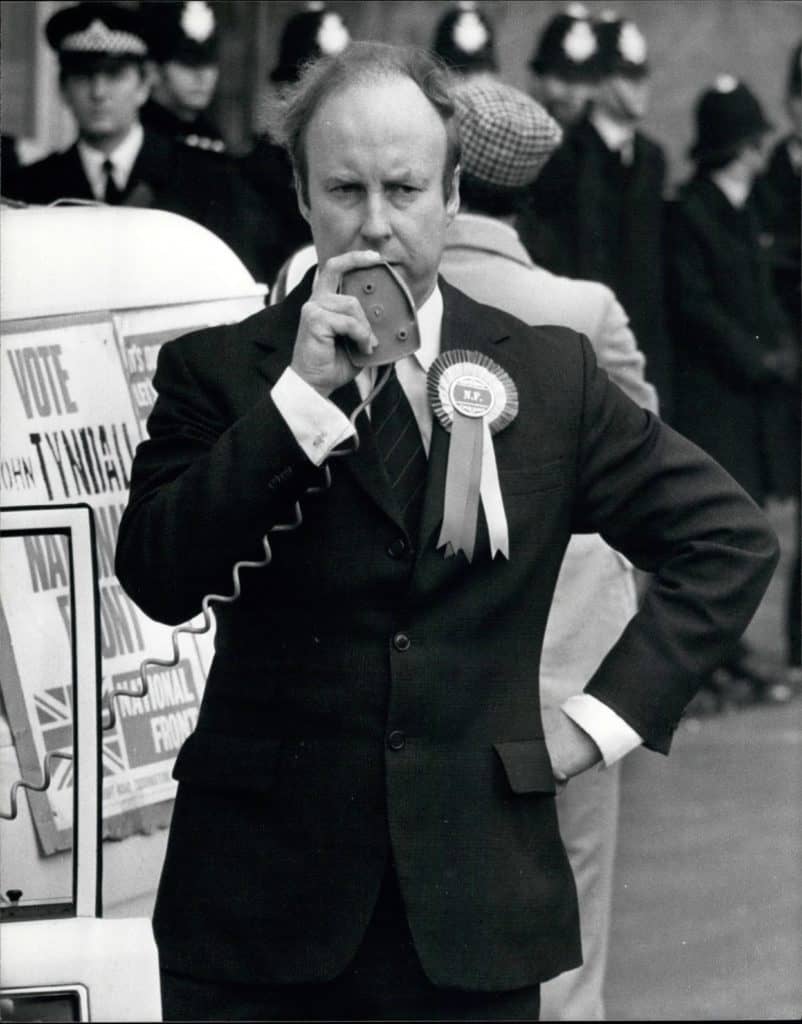

Pro-white author and activist John Tyndall. (Credit Image: © Keystone Press Agency/Keystone USA via ZUMAPRESS.com)

It is my understanding that Americans are currently being softened up for the introduction of so-called “hate laws” — legislation similar to that existing in Canada and most Western European countries, which makes it illegal to say, write, publish or distribute anything which could be construed as stirring up “racial hatred” against an ethnic group. I have actually served a term of imprisonment in Britain under such a law, and Americans may find my experiences instructive.

British legislation is currently codified within the Public Order Act, of which Part III deals with “racial hatred.” At one time the prosecution in a case of this kind had to prove that a defendant intended to stir up hatred. Intent is difficult to prove, so the law was broadened to make conviction possible without proof of intent, providing it could be shown that racial hatred resulted from what was said or written. This too was difficult to prove, so the law was further extended to include the concept of “likelihood.” Even if intent cannot be proven, and even if no hatred can be shown to have been stirred up, the mere likelihood that hatred might result is sufficient for conviction.

It was on this basis that I was charged in 1986, with having “conspired . . . to publish divers items of written matter which were threatening, abusive or insulting in cases where . . . hatred was likely to be stirred up against racial groups . . .” I am editor of Spearhead, which is published by the British National Party, and it was mainly in that capacity that I was said to have offended. John Morse, editor of British Nationalist, was charged with the same crime, and we undertook a joint defense.

Naturally we asked for information on the specific passages that were considered to have landed us on the wrong side of the law but we never received this information. It became obvious that the prosecution’s strategy was to produce in evidence as much material dealing with racial matters as the jury could be expected to digest, and hope that the general impact would shock the latter into finding against us.

Even after we had been found guilty, we were never told which actual words were considered by the jury to have been unlawful and which were not, and we have had to surmise, in the light of the emphasis that the prosecution placed on each piece of evidence, which were the ones that were our undoing. My own feeling is that it was not so much one specific reference that tipped the scales but the cumulative effect of all the material.

Nevertheless, we consider that one of the major causes of our being found guilty was an editorial in the May 1985 issue of British Nationalist dealing with the South African situation. In this article certain races were referred to in terms of superiority and inferiority. In the witness box we were asked what we meant by “superior” and “inferior” and we replied that we were referring to the accomplishments of the respective races throughout the world, and in particular Africa, and the criteria we had in mind were the particular arts and capabilities required for the construction of our own civilization. We were not attempting to establish any absolute and all-embracing standard of what was superior and what was inferior. This explanation apparently did not suffice.

One article from Spearhead that may be considered a possible cause of conviction was one that appeared in the August 1984 issue. This was in fact a reprint from an American publication, which affirmed the belief that there existed a global race war and that in that war there could be no neutrals. Today it would probably not be overstepping the bounds of “legality” to use the expression “race war,” or indeed to admit that such a thing is in progress. What would, on the other hand, not be prudent would be to suggest: (1) that the race war is the responsibility of any specific racial group; and (2) that in such a war whites should take up a position of defense of their own side. Another item in Spearhead that is likely to have contributed to my conviction was a different article published in the same August 1984 issue. It contained decidedly unfavorable references to the standards of morality achieved by certain racial groups. Clearly, such outright condemnation of the morality of any identified racial group must now be regarded as “dangerous.”

In our defense we offered ample evidence that words which could be classified as “threatening, abusive, or insulting” had been repeatedly used against whites in this country, but this was not considered relevant. The jury found us guilty.

The Jury

During the week of the trial, Mr. Morse and I made a close study of the jury and of its reactions to the court proceedings. We had eliminated all non-whites from the panel by exercising the right of objection (though this is no longer possible because of changes in the law). Our assessment was that the jurors were mostly a timid-looking bunch likely to go whatever way a strong argument took them.

We did not know who the foreman was until the moment of the verdict, when he identified himself. He looked like a small-time trade union official and a possible Labour Party activist, and his personality appeared just a shade stronger than those of the others. We guessed that it was his hectoring of his fellow jury members that probably swayed them into deciding against us.

Undoubtedly, however, the judge in his summing up address to the jury played a part too. His tone clearly indicated that in his opinion we had crossed the line between mere expression of views about race and the voicing of hatred — or at least the encouragement of hatred — and had thus broken the law. His imposition of a sentence of one year’s imprisonment — later reduced on appeal to six months — confirmed this, for he could have given us a considerably lighter penalty.

On reflection, my reckoning is that the jurors most certainly did not go over every piece of evidence with a fine-toothed comb and interpret it with legalistic precision. It is much more likely that they concluded: “Well, it seems that the judge thinks these two are dangerous characters who must be given a lesson — and who are we to disagree with him?”

On the other hand, the jurors did not reach their verdict all that quickly. My guess is that this was primarily because they could not at first agree and it took some time to convince the waverers. Whatever the reasoning, two British subjects, on trial in their own country, under prosecution by a department of their own government, were sent to prison for six months for expressing their opinions.

I should point out, though, that in Britain, just as in the United States, there are areas of the country where the local population consists of plenty of robust-minded folk who will not easily be swayed by glib “liberal” rhetoric. In the county of Kent, in a town about forty miles from London, a colleague of mine was acquitted on a race charge when a jury refused to be intimidated by the prosecution’s arguments. The same thing happened to another defendant I know of in the North East of England. Our trial took place, however, in Inner London and the result was different: a weak jury deferred both to the judge and to the jury foreman, whatever the individual jurors’ innermost feelings may have been.

Behind Bars

After sentencing we were assigned to Wormwood Scrubs Prison. Upon arrival we put in an application to go on what is known as “Rule 43,” which provides for the segregation of prisoners from the rest of the inmates. [This is what is called “protective custody” in the United States.] The reason for our application was that at the time of our imprisonment, about one fifth of Britain’s prison population was black, and in areas of high immigrant concentration like London the proportion was higher still. In an exercise yard that we could see from our cell we once counted over 60 blacks out of a total of about 180 prisoners.

Racial conflict has become a major problem in British prisons. Blacks have the advantage due to their tendency to stick together and hunt in packs, while whites do not show the same solidarity. We also learned that it is common for blacks facing punishment for offenses against prison officers to claim that the officers made “racist” remarks. Mr. Morse and I could see that the same defense might be offered by a black who was caught assaulting us, and by “going on Rule 43” we could avoid trouble of this kind.

Rule 43 has an adverse side, however. A fairly large proportion of our neighbors consisted, as one prison officer warned us it would, of the absolute scum of the earth. Prisoners who have to apply for protection in jail are, very largely, child molesters and child murderers (often the same people), rapists and informants. The company we had to keep was far from pleasant and we had as little contact as possible.

When a man goes to jail he can either regard his sentence as a slice taken out of his life or as a part of his life during which he can do things he might not otherwise be able to do for lack of time. For several years I had been planning to write a book, and had made a modest start a month or two before I was sentenced. I resolved immediately that I would get as much of the book done as possible, and in the event I almost completed it.

Mr. Morse and I also embarked on a program of exercise, and we discovered how a bit of improvisation can turn a prison cell into a gymnasium. For example, one can load all the furniture in the room — in our case, two tables and two chairs — onto one of the beds. Then gripping the bottom crossbar at the end of the bed, one can curl the bed to shoulder height.

Soon after we arrived we had a visit from the Padre. On learning what we were in for, he set himself the task of saving our souls — which meant converting us to internationalism, liberalism, multi-racialism, and world peace. From the start he could see that we were difficult pupils but he seemed to want to persevere. At first we did not mind his coming because it made a bit of a change to talk to someone else. However, after several conversations we got tired of his silly slush and decided we would have to discourage him. He soon concluded that Tyndall and Morse were hopeless cases who seemed to get worse rather than better as a result of his lectures; we were then able to get on with more useful things.

I should add that throughout our time in jail we were treated extremely well. The average prison officer is representative of the best qualities in the British race. Our jailers knew why we were there and their behavior toward us indicated that they respected us and what we stood for. Some professed open sympathy while the others simply indicated by the way they spoke to us that they did not regard us as common criminals. One of the prison staff summed it up shortly before our time for release: “You two are only in here for saying what three quarters of the country is thinking!”

What Can One Safely Say?

Since my release from prison I have had reason to reflect on what one can and cannot say in this country, and I personally do not believe “race-hate” laws in Britain to be anything like as much of a handicap to free discussion as some of my friends and political allies believe them to be. In a way, they can even be looked at as something of an advantage inasmuch as they impose a certain discipline in the use of language which is desirable in any case. I have, for example, read some American publications in which the writers, because they are free of legal restraints, express themselves in terms that are so crude and offensive that they are likely to alienate a great many would-be readers and appeal only to the mentally maladjusted.

Since resuming editorship of Spearhead I have found that one has a fairly wide area of freedom to expound on racial differences, provided that one emphasizes that one is referring to just that: differences, and not questions of superiority or inferiority. This may require an approach that is distasteful to one’s sense of honesty, but if it is a question of keeping out of jail one simply has to suppress certain emotions. In any case, I have discovered that an emphasis on differences provides an extra layer of armor-plating against the law. By talking about differences one can speak with comparative openness against the cultural standards and living habits of other races while not risking prosecution.

Even in the case of descriptions of superiority and inferiority, one can get away with these providing they are used in a certain context. As the law in Britain currently stands, I am fairly confident that I would not be prosecuted for writing that the academic performance of West Indian children is inferior to that of white children, for the fact is so obvious and widely recognized — even by liberals — that to convict someone in court for saying so would reduce the law to absurdity. For the same reasons it would be pretty safe to say that the athletic performance of young blacks is, in certain fields, superior to that of young whites.

It is another matter, however, to take things further and say that such superior and inferior performances are the consequence of inherent genetic factors. Here one would probably be on thin ice speaking of white intellectual superiority though probably not when speaking of black athletic superiority.

The judge at our trial exhibited the typical do-gooder liberal attitudes in this respect. He could not possibly gainsay, and therefore condemn someone for saying, that blacks perform intellectually at a lower level than whites. At the same time his emotions could not bear the thought that this state of affairs was unchangeable and not capable of remedy by education and social engineering. The first thought was just about acceptable to him; the second was not. It is essential to the liberal’s faith in his ability to guide people forward that he have the capacity to lift up the low by civic action, whatever their depressed condition. Offend that faith, and you make the liberal very angry! Once again, it is my opinion that in Britain we still retain considerable freedom to express ourselves on matters of race, but we need to be careful when venturing into fields of genetics and heredity.

Advice for Americans

Should Americans eventually have to face “hate” laws similar to ours, they should bear in mind that they will have been introduced not for the high-sounding purpose of “stopping hatred” but to gag certain people. In other words, their object is to shut you up, but with the humbug that is characteristic of legislators in all “democracies,” they prefer to do this while maintaining the pretense that your right to express your opinions still remains inviolate. Theoretically, all opinions can still be expressed and it is only the stirring up of hatred that is off limits. Decisions to prosecute can therefore be expected to be based not on any genuine concern for the public interest but on the basis of whether the authorities think that, on the evidence of what you have said, they have enough to “hang” you.

It is good to recall that part of the policy of gagging “racists” consists of intimidating people with the threat of the law rather than actually enforcing it. In other words, the purpose of legislation on “racism” will largely have been accomplished if people are induced to believe, albeit mistakenly, that they are not allowed to say anything about race and racial differences, and that they must speak of other races only in flattering terms. A great many people in Britain have been frightened by the existing race laws into thinking just this, with the result that they do not exercise their still-existing rights to speak on racial matters.

I have one further consideration. There may be some in the United States who will be inclined to take the view, “Publish and be damned!” with the idea of courting prosecution, conviction and thereby martyrdom. That would, of course, be up to Americans to decide — with a careful eye to probable political effects in a country where the history of free speech may be different from that of Britain.

I can say only that in this country martyrdom achieves very little. The whole concept of calculated martyrdom rests on the supposition that masses of people are going to be made aware of it, and that they are going to be so outraged that it will be worth the sacrifice involved. Our case here in 1986 was given only the tiniest coverage by the media, and the national climate at the time was one of such apathy that it is doubtful that the matter would have aroused much emotion even had many people known about it.

I certainly hope that Americans will not permit themselves to be gagged by means of “hate” laws and that it will continue to be possible to discuss not only the genetic basis of racial differences but any other matter that a free people should wish to investigate. Nevertheless, in closing, I would repeat the view that “hate” laws need not curtail debate to an intolerable degree and that they can even serve the useful function of deterring the publication of crude, offensive materials that only hurt our cause.