The Zebra Killings

F. Roger Devlin, American Renaissance, January 8, 2020

Editor’s Note: This 9,000-word account is the best summary you will find anywhere of a largely forgotten series of grisly black-on-white murders.

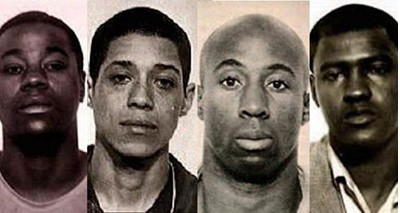

They will never be as celebrated as Emmitt Till, but 15 white San Franciscans were killed because of their race over a terrifying six-month period in the early 1970s. The killings, which became known as the Zebra murders, were carried out by a group of at least four black men associated with the Nation of Islam.

On the evening of October 20, 1973, 30-year-old Richard Hague and his 28-year-old wife Quita, were strolling down Telegraph Hill, barely a block from home, when a white van pulled up beside them. Three black men emerged; one pointed a gun at them and ordered them to get in the van. Quita ran off, but the men grabbed Richard. Thinking their intent was merely robbery, and that they would be let him go if they cooperated, she went back. The blacks threw them to the floor of the van and tied their hands behind them. Richard thought the men might be raping Quita and tried to look up; they beat him unconscious with a wrench.

Arriving at a suitably deserted spot, the men dragged Quita and the unconscious Richard out of the van. They then set upon Quita with a machete. One of the investigating officers recalls:

I’d been in the department ten years. Knifings, shooting, beatings, strangulations — pretty much any way you can kill as person, I’d seen it done. But I’d never seen anything like the wounds that cut through that young woman. They took your breath away. . . .

There was no sexual assault. Her husband’s wallet was stolen, but there was almost no money in it. Even if robbery had been the motive and the killers were just trying to silence them, they could have used their gun. But they didn’t. Which meant they didn’t just want to kill them. They wanted to mutilate them. . . .

The wounds were across her face, shoulders, chest and torso. That meant the killers attacked her while she was on her back. There was tearing in most of the cuts, which meant she was struggling, trying to twist away from the blade as it came down toward her. [pp. 3–17. See end of article for explanation of sources.]

The killers were content to slash at Richard’s face and neck a few times and leave him for dead. He survived, but needed more than 200 stitches and many surgeries.

Ten days later, Frances Rose, 28, was driving to class at the University of California Extension Campus when a black man flagged her down. He got in the unlocked passenger door and unloaded four .22 caliber bullets into her, killing her instantly.

The killer headed down Laguna St. and turned onto Haight St. This time there were witnesses, and a description was radioed out to police. A patrol car cruising down Haight St. spotted a match. Patting the man down, they found his revolver and arrested him.

The man’s name was Jesse Lee Cooks, a criminal with convictions for major felonies and a history of violence when committing crimes. He had been paroled from San Quentin the previous June after serving a seven-and-a-half-year sentence for bank robbery. According to a fellow prisoner who had known him, Cooks liked to talk about violent daydreams, e.g.: “What I plan to do someday is raid a white orphanage and take all the little white kids by their feet and swing them like a baseball bat and smash their brains out against the wall.” [Howard pp. 30] On another occasion, he had said:

I’d like to raid one of those hospitals where old white people live. You know, man, one of those places where they just sit around all day slobbering all over theyselves. Man, I’d like to just go through a place like that an off them all, every one of the old motherfuckers. Use a blade and really hack them up. [Howard pp. 30–31]

According to this witness, his fantasies always involved attacking people too weak to fight back.

San Francisco was probably lucky that police captured this psychopath early on. Cooks had raped a local woman just the previous week, but police did not learn for a long time that he had been the main instigator of the attack on the Hagues. He was off the streets, but his associates would continue to terrorize the city for several more months.

Four weeks passed. On the morning of Sunday, November 25, Sammy Erekat, age 53, was opening “Erekat’s” — the family grocery he had owned and operated for 13 years. A black man entered and drew a gun, ordering him to the lavatory in the back of the store. He then tied Erekat’s hands behind his back with a necktie and shot him in the back of the head. Before leaving, the man cleaned out the safe and the cash register, netting $1,300. Because Erekat’s hands were tied, investigators suspected that robbery had not been the primary motive. Witnesses also reported a black man standing near the front door of the grocery at the time, apparently acting as a lookout. Two experienced investigators, John Fotinos and Gus Coreris, took on the case.

Erekat was not, strictly speaking, white: “Sammy,” the name by which his neighbors knew him, stood for Saleem, and he was a first-generation immigrant from Jordan. But to his killers, he was white enough. Well-known and popular in his neighborhood, Erekat’s funeral attracted 250 mourners and the cortege was 85 cars long. The Arab Independent Grocers Association put up a reward of $5,000 for information leading to the arrest of the killers.

Sixteen days later, witnesses saw either one or two black men approach 26-year-old heroin addict Paul Dancik at a public telephone in the Fillmore District and shoot him dead at point-blank range; no altercation, no robbery. The crime lab made a significant discovery: The .32-caliber bullets that killed Dancik were fired from the same gun used on Saleem Erekat. Criminals seldom re-use guns, preferring to dispose of them as incriminating evidence.

Two days later, killers struck again — twice. Art Agnos, 35, had been involved in local politics for ten years. After dusk on December 13, he was leaving a meeting when some women stopped to speak with him. He heard two loud bangs which he thought were firecrackers and felt what seemed to be someone bumping into him from behind. The women ran away terrified. He started after them, telling them it was only firecrackers. They shouted back that he had been shot. Agnos then turned around and saw a black man staring at him from only 15 feet away. The man pivoted and ran. Only then did Agnos feel the pain and dampness from the blood soaking through his shirt. He got immediate help and survived. Fifteen years later, he served a term as mayor of San Francisco.

Art Agnos

The same night, 31-year-old Marietta DiGirolamo was out looking for her boyfriend. As she strolled down Divisadero St., a black stranger shoved her into the doorway of a barbershop. Indignant, she shouted: “What do you think you’re doing?” He then fired three bullets into her and ran. A witness called an ambulance, but she was pronounced dead at the hospital. Her boyfriend, a black cocaine dealer, was briefly suspected, but he had a solid alibi and was clearly distraught over her death. Indeed, through his professional channels he offered a private reward for information on the killer. The reward was calculated to appeal to the ghetto-dwellers he thought most likely to know something: three ounces of pure cocaine, plus $5,000.

The city’s crime lab soon confirmed that the gun used on Agnos and DiGirolamo was the one used on Saleem Erekat and Paul Dancik. (The attacks on the Hagues and Frances Rose were not known to be related.) Investigators began referring to “the thirty-two-caliber killer.” Witness reports all pointed to one or more young black men as the perpetrators, and emphasized the unprovoked and seemingly random nature of the shootings. The police were beginning to suspect a racial motive.

There were a number of radical groups besides the Nation of Islam (NOI) in the Bay Area at this time, including what was left of the Black Panther Party and such offshoots as the Black Guerrilla Family and the Black Liberation Army. A new arrival was the mixed-race Symbionese Liberation Army, which catapulted to fame after it kidnapped Patty Hearst in 1974. Investigator John Fotinos suspected NOI from the beginning because witnesses reported that the killers were clean cut and neatly dressed.

Another week passed. On the evening of December 20, 81-year-old Ilario Bertuccio was walking home from his job at the local 7-Up bottling plant. A black man approached from the other direction, fired four bullets into him and ran to a waiting getaway car. Bertuccio died almost instantly.

Across town that same evening, 20-year-old college student Teri DeMartini was driving home from a Christmas party. As she neared her home on Central Ave., she passed a double-parked car with a black man at the wheel. Struggling to park her car in a tight spot, she noticed another black man approach the driver of the double-parked car. As she got out, she saw that the same man now approaching her, his hand in his pocket. Without warning, he pulled out a gun and fired four shots, of which three struck her. She survived, but was paralyzed.

By now, no one was surprised when .32 caliber shell casings were recovered at both scenes, nor that the shooters were black and the victims white. The next day, the San Francisco Police Department assigned its two black homicide detectives, Rotea Gilford and Prentice Sanders, to the case full time, assisting chief investigators Fotinos and Coreris.

There were racial tensions within the SFPD itself. Both Gilford and Sanders were in an organization called Officers for Justice that was suing the department for discrimination, making them unpopular with top brass and many white colleagues. But policing is a line of work where race matters, and the men had an intimate knowledge of blacks in San Francisco.

Two days later, December 22, killers struck again. Nineteen-year-old Neil Moynihan was carrying a teddy bear he had just bought as a Christmas present for his younger sister when he was gunned down by a stranger. Witnesses were unsure of the killer’s race, but one claimed to be certain the man was black because he “ran black.”

Six minutes later and practically just around the block, 50-year-old Mildred Hosler had finished work and was heading for the bus. A man ran toward her from across the street and fired five bullets into her upper body at nearly point-blank range. She and Moynihan both died at the scene.

Witnesses to the .32-caliber-killings described more than one automobile type as the getaway car, or simply as being in the vicinity of the crimes, but the one most frequently mentioned was a light-colored, four-door Dodge Dart. Driving in their squad cars near the Moynihan and Hosler crime scenes several hours later, Gilford and Sanders spotted a car matching the description and followed it. The driver led the detectives on a merry chase through a neighborhood of winding alleyways and finally shook them. Whoever the driver was, he seemed to know the neighborhood even better than the police did.

The detectives then spent several hours asking around the area. This was mostly fruitless, but Sanders noticed a two-story warehouse that housed a moving and storage company called Black Self-Help. It belonged to the NOI. He recalls:

I’d driven by there countless times, so it wasn’t like I’d never seen it before. But that night it stood out to me. I noted the building. Noted that it was in the vicinity of the shootings and that its backside faced the alleys where we had lost the other car. [98–99]

Just two days later, on the morning of Christmas Eve, a bag containing a mutilated corpse was discovered on the beach in San Francisco’s Sunset District. It was thought to be a young man between the ages of 20 and 30, but it was castrated, and the head, hands, and feet were hacked off. The legs were trussed up and held against the chest with wire. With grim humor, the SFPD cops nicknamed their discovery “the Christmas Turkey.” Investigators could not identify the victim because he had no fingers and no teeth. To this day, he is “unidentified body #169.”

The Sunset District (Credit Image: Robert Ashworth via Wikimedia)

There were no bullet wounds, nor anything else to connect the case with the .32-caliber-killings, but it reminded investigators of something else. Black detective Prentice Sanders recalls: “Those of us who saw Quita Hague couldn’t look at this body without making a connection. It wasn’t just the kinds of wounds. It was the violence of them.” [101]

That evening, Gilford and Sanders were once again cruising the streets where Neil Moynihan and Mildred Hosler had died when they suddenly spotted the Dodge Dart. They followed it, and this time the car slowed down and stopped.

The driver was a tallish, thin, fair-skinned black man about 20 years old. He identified himself as Larry Green, living on Grove Street in the Filmore District, and employed at Black Self-Help, which meant he belonged to NOI. He made a mocking show of politeness, ending every sentence with “sir:” “yes, sir” and “no, sir” and “absolutely not, sir.” Both detectives got a strong sense that the man was guilty of something. Sanders remembers: “It was his look, his manner, everything. It was in the air. You could smell it.” [105]

In the passenger seat sat a slightly older, darker-skinned and more muscular man. Sanders recalls: “I told him to put his hands up on the dashboard where I could see them. But he never turned to look at me. Just kept staring straight ahead, a look of outrage on his face. Like he’d take me apart if he could.” [103] For NOI, black cops were the lowest of the low — traitors working for the white man.

Gilford asked Green if he could take a look in the trunk. Sanders recalls:

Green didn’t know what to say at first. He’d been putting on this show of cooperating, but you could see him tense up when we asked for something real. Finally, he agreed. We were hoping to find physical evidence — a gun, bullets, a wig — anything that might give us a reason to bring him in. But we got nothing. All there was in that trunk were stacks of [NOI newspaper] Muhammed Speaks. [105]

With no grounds to detain the men, they reluctantly let them go. Sanders remembers seeing Green smile, pleased with himself, as he got back into the Dodge. Back at the station, Gilford and Sanders ran a search on Larry Green; he had no criminal record.

The detectives’ hunch had been correct, though: Green and his passenger were involved in the murders of the previous two months. More than four months and 10 more shootings would pass before they could be brought to justice.

* * *

Larry Craig Green was born in Berkeley, California, in 1953. His father had a good job with the University of California system, the family was intact, and both Larry and his sisters did well in school. He went on to study at two community colleges while working various jobs. It is unclear how he discovered NOI, but once he did, he dropped out of college, quit his job at a white-owned company, began attending services at San Francisco’s Temple No. 26, and went to work for Black Self-Help Moving and Storage.

This company gave jobs to young black men who were either members of NOI or thinking of joining. Many such men were recently released convicts and practically unemployable anywhere else. Black Self-Help undoubtedly served a useful function by offering them a chance to rebuild their lives. But there was another aspect: The owner often invited speakers to talks to employees, and frequently stirred up hatred against whites. One speaker, for example, discussed the Watts riots of 1965 and showed a film of blacks being beaten by police and National Guardsmen. Speakers studied the audience reactions and gauged the effectiveness of their propaganda.

NOI gave its followers a catechism of 14 lessons to study and memorize. Particularly noteworthy is the 10th lesson, which speaks of the Muslim’s duty to “murder the devil:”

Muhammad learned that he could not reform the devils, so they had to be murdered. All Muslims will murder the devil because they know he is a snake and also if he be allowed to live, he would sting someone else. Each Muslim is required to bring four devils. [107]

Since NOI referred to whites as “devils,” it seemed to some of the simple souls at Black Self-Help that killing white people was a religious duty.

That was where Larry Green spent his days. Young as he was, he became a kind of mentor to some of the older ex-cons, most of whom had had childhoods far more difficult than his. Whatever they had done, he viewed them as “brothers.” He would lend them his car, find them a place to stay, and even invite some over for dinner at his parents’ house in Berkeley.

One of the men Green met at Black Self-Help was violent repeat felon Jesse Lee Cooks, whom we have already encountered. Another was Anthony Harris, who had also been in and out of prison for most of his adult life. As a young man, Harris had married a white woman, fathered two children by her, and abandoned her. From 1971–73, he was in San Quentin on a charge of burglary. During this time, he joined NOI and met Jesse Lee Cooks. He was released on parole just a few weeks after Cooks, in August 1973.

Harris married a woman from Temple No. 26 but found a new girlfriend in less than a month. Through this woman, Larry Green met and married a young woman who belonged to NOI; Harris served as witness.

The man detectives Gilford and Sanders had seen in Larry Green’s passenger seat during that Christmas Eve traffic stop was J. C. Simon from Opelousas, Louisiana. A book on the murders describes him:

Since before moving out west, Simon had lived a gypsylike life, dropping out of college, roaming around Texas, marrying, fathering a child, then abandoning both wife and child to come to California. In San Francisco he had married another woman, then left her and got involved with someone else. Throughout all the changes there was one constant: a bitter dissatisfaction with life that fueled the transformations and often came out as a rage-filled, controlling anger. [114]

J. C. Simon was now in his late twenties. He was not an ex-con; his criminal record was limited to a plea of no contest for possession of a stolen gun some years earlier for which he had served no time. Like Larry Green, Simon had worked his way up to a supervisory position at Black Self-Help. Both men had the keys to the place; either could open up in the morning or close at night. They shared an apartment about midway between Temple No. 26 and their workplace.

In November, following the arrest of psychopath Jesse Lee Cooks, another San Quentin parolee found his way to Black Self-Help. Manuel Moore had attended California public schools as far as the 10th grade without ever learning to read or write: He could only sign his name and recognize a few words. He began stealing at the age of 13.

Before his seventeenth birthday, he was arrested twice for violation of juvenile curfew, and investigated for six burglaries and one car theft. After that it was anything and everything: suspicions of robbery, battery, burglary, forcible rape, possession of alcohol by a minor, failure to appear on traffic citations, receiving stolen property, possession of marijuana, violation of probation, drunk driving . . . . [Howard 99]

Following several shorter prison terms, Moore served two years and three months in San Quentin for second-degree burglary. Upon parole, he managed to stay out of trouble for 13 months. Then he returned for a year as a parole violator. It was during that year he joined the prison’s NOI congregation, where he met Anthony Harris. Upon release in November 1973, Moore showed up at Black Self-Help. By December, he was taking part in the killings.

* * *

Following the events of Christmas Eve, 1973 — the discovery of unidentified body #169 and Gilford and Sander’s inconclusive traffic stop of Larry Green — the killings let up for more than five weeks. This was no doubt partly related to heavy snowfall and the worst cold wave in 20 years. By that time, San Francisco was on edge, and not just the white population. Prentice Sanders recalls:

People in the Filmore [a heavily black neighborhood] were as scared as anyone. Part of the reason was the fear of a white backlash. They knew that if anybody went looking for revenge, they wouldn’t waste time trying to find out who it was who did the shooting. They’d just head to the ghetto and wreak the same kind of havoc that was coming their way. [101]

Indeed, the killers may have meant to provoke retaliation.

Gilford and Sanders’ connections among blacks were not paying dividends: “When stuff goes down in the ghetto, you hear things,” recalls Sanders; “This time, we didn’t.” [102] The silence was especially surprising in view of what Gilford and Sanders called the “ghetto reward” put up by Marietta DiGirolamo’s boyfriend. Sanders explains:

The street price for a gram of coke was about fifty bucks back then. This was pure, so you could step on it [i.e., dilute it] five or six times, easy, before it hit the streets. That meant each ounce was worth from five to eight thousand dollars. You add cash to that and he was putting up between twenty-five and thirty thousand dollars for information. That was serious money. Hell, I only made about sixteen a year before overtime, and I had to pay taxes. He was offering what amounted to a fortune in the ghetto. Gil and I figured something had to come from that. It was too much money for people to walk away from. Someone had to snitch. [79]

Yet no one did. This reinforced suspicions that the murders were the work of a disciplined group.

A police shooting on January 25 was the spark for more killings. An officer stopped an NOI member driving a van. There was an argument, three more blacks got out of the van, a scuffle broke out, and police shot one of the blacks in the spine, paralyzing him for life.

Word spread quickly within Bay Area NOI congregations. Minister John Muhammad of San Francisco’s Temple No. 26 announced a public meeting for Sunday, January 27. Well over 2,000 people showed up, more than half of whom were not NOI members. Also in the audience were Larry Green, Anthony Harris, J. C. Simon and Manuel Moore. That evening, the four met along with four other unidentified men at Simon’s apartment. Among the proposals for avenging the paralyzed man were dynamiting a school bus full of white children and shooting at an airliner with a high-powered rifle as it took off. According to Anthony Harris, he objected that such actions might kill Muslims or blacks as well as whites. Simon flew into a rage, complaining that Harris was critical of every plan for dealing with the “blue-eyed devils,” and ordering him out of the apartment.

But then Simon softened, saying that he understood it took time for someone to be ready to kill. No sane person would want to make killing a habit. But this was something they had to do because whites were evil, and getting even with them was necessary not only as revenge for Larry Crosby but because of generations of wickedness. His anger spent, Simon told Harris he was sure that when Harris was ready to get even with whites, he would rise to the challenge, adding that they would never force him to do something against his will. Then Harris claimed that he left the meeting while the others continued talking. [130]

The following afternoon, January 28, J. C. Simon and Manuel Moore are known to have driven to the East Bay, possibly to confer with members of Oakland’s NOI Temple, where the paralyzed man was affiliated. They drove back to San Francisco around 4:30 PM and went to Black Self-Help just as Anthony Harris was preparing to leave in search of Larry Green. An occasional drug user, Harris had taken a couple “reds” (barbiturate Seconal) and was feeling woozy. Simon offered him a ride. The car was a black Cadillac that belonged to the owner of Black Self-Help. Along with Larry Green’s Dodge Dart, this was the principal car used by the killers.

The trio set off, with Simon driving, Moore in the passenger seat, and Harris in the rear. First they headed to Temple No. 26’s Fruit of Islam house, a residence for young men where Simon believed Harris might be able to find Larry Green. While Harris went inside, Simon walked back to Geary Boulevard where he shot 32-year-old Tana Smith dead as she waited at a bus stop.

Not finding Larry Green, Harris popped two more “reds” and went back to the car, where Simon offered him another ride. The Cadillac headed south. About six blocks from where he had shot Tana Smith, Simon spotted 69-year-old pensioner Vincent Wollin walking home. He shot him dead, and drove off again.

Heading east into a run-down area south of Market Street, Simon found a third victim standing across from a gas station: 84-year-old John Bambic. Simon stopped the car, ran across the street, and shot Bambic twice in the back. Although one of the bullets pierced his heart, he somehow managed to turn around and grab on to his assailant. After a few moments of struggle, he dropped to the pavement, dead.

The car headed south to a mixed-race neighborhood around Silver Ave. A laundromat stood at the corner of Brussels St. Several customers were present, but only one was white: 45-year-old Jane Holly. This time Manuel Moore was the trigger man, bursting in to shoot Holly in the back, then leaving without a word. Witnesses saw him run around the corner to the waiting Cadillac. Anthony Harris, in the back seat and still high on drugs, remembered the car going airborne as it sped away, slamming his head against the roof.

Just a mile and a half away, 23-year-old Roxanne MacMillian was moving her belongings into a new apartment on Edinburgh Street when an approaching black man said “Hi.” She said “Hi” back and started up the stairs. Two bullets struck her from behind, leaving her paralyzed. She was the fifth victim of the evening, and the only one to survive.

As news of the killings spread, terror gripped the city. City buses filled to overflowing with people headed home, then turned eerily empty. SFPD investigators had no time to study one crime scene before word of a new shooting came in. “It felt like the gates of hell had opened,” recalls Prentice Sanders. [146] Yet he knew there was no chance of catching the killers that night: from Edinburgh St., they could easily reach Highway 101 and head anywhere.

There was one more incident later that night, across the bay in Emoryville. It was one o’clock in the morning of January 29, several hours after the last shooting in San Francisco, and 26-year-old Thomas Bates was hitch-hiking beside an on-ramp leading to the Bay Bridge. Bates saw two black men pull up in a dark Cadillac; one rolled down a window and fired three shots at him before the car disappeared across the bridge. As previously noted, Simon and Moore were known to have been in the East Bay area the previous afternoon, so it is likely they were responsible for this shooting as well. Thomas Bates made it to a nearby Holiday Inn and survived.

The next morning’s headline screamed “S.F. KILLING SPREE. TWO-HOUR DEATH DRIVE.” The mayor of San Francisco held a press conference to announce plans for a massive manhunt. It would be code-named “Zebra” because the Z channel on police radios was being dedicated to it. The SFPD issued an unprecedented warning to all city residents to stay off the streets at night. Oddly, it denied there was any evidence a radical group might be responsible for the crimes. However, police put Temple No. 26 under round-the-clock surveillance with a powerful camera atop the nearby Miyako Hotel. It was the same type of camera the CIA used in spy planes, but it never caught anything that would have provided grounds for a search warrant.

San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen received an anonymous phone call: “You read the paper, right? Five white men dead, right? Tonight, we’re going out and getting us ten black men. Two for one is about right, don’tcha think?” [148] The man then hung up.

Meanwhile, the Zebra killers (as they were now known) quietly went back to work at Black Self-Help Moving and Storage.

You see the same pattern with a lot of terrorist groups [notes Prentice Sanders]. There’ll be a surge in violence that creates a wave of fear in the public and makes the police step up their investigation. So the terrorists shut down for a while. Eventually they come back with another surge, and when they do the wave of fear that follows grows exponentially. [162]

Anthony Harris, however, left Black Self-Help and moved across the Bay to Oakland. He later claimed this was because he had been unnerved by the January 28 killings and feared that his own life was in danger. The owner of Black Self-Help disputes this, saying he fired Harris. Whatever the reason, Harris had no further contact with J. C. Simon or Manuel Moore. He continued to communicate intermittently with Larry Green.

A .32 caliber pistol was used for the shootings of January 28, but not the same one as in the previous murders. There were many witnesses this time, but their testimony yielded little except vague physical descriptions of the killers. Zebra investigators put in hours of overtime, but had little to show for it. For the whole of February and March the trail went cold.

* * *

On April 1, 19-year-old Thomas Rainwater and 21-year-old Linda Story, cadets at the Salvation Army School for Officer Training in San Francisco, were strolling down Geary Boulevard. As the couple approached the corner of Webster St., a man emerged and walked past them. Then he stopped, drew a gun and fired two bullets into Rainwater’s back at nearly point-blank range. Pivoting toward Linda Story, who was already running, he fired three more times, hitting her twice. She survived; Rainwater died.

There were plenty of witnesses, as well as two plainclothes officers just across the street. A patrol car was cruising only a block away, and if the killer had fled in the opposite direction, he would have run right into it. As it happened, he ran into a nearby apartment complex and disappeared, leaving no trace but the usual .32 caliber shell casings. Within minutes, 50 police officers were swarming the neighborhood, but found nothing. Those who suspected NOI involvement noted that Temple No. 26 was just a block from away.

In the nights that followed, the SFPD quietly instituted a “Zebra Patrol” of dozens of unmarked cars. The hope was that one such car might be present the next time the killers struck. The Department’s lead investigator admitted publicly that the police felt “helpless.”

Thirteen days later, on Easter Sunday, April 14, 1974, 18-year-old Ward Anderson and 15-year-old Terry White were waiting for a bus on the corner of Hayes and Filmore. A black man turned the corner onto Fillmore, walking rapidly. Ward Anderson asked him for a cigarette. The man grunted and continued walking. Then, suddenly, he turned around and fired two bullets at Anderson.

Terry White turned at the sound of the shots. The man approached him and fired three more times. From the sound, Terry thought it was just an air gun. The man then ran down the block to Grove St. and disappeared. Ward Anderson cried out that he had been shot. Terry doubted this, but decided to run for help just in case. Soon he felt blood dripping from his own arm and side. He sank down in the street as onlookers began arriving. Paramedics appeared and both men survived.

Two days later, 23-year-old Nelson Shields was helping a friend pick up a rug in the city’s Ingleside neighborhood around 9:30 PM. As he arranged the contents of his station wagon to make room for the rug, three shots struck him from behind. Nelson Shields was the fifteenth “Zebra” fatality. Once again, investigators found the usual .32 shell casings and heard the usual vague descriptions of black men running from the scene.

The horror and fear provoked by serial murders such as Zebra is cumulative, and it was now reaching a crisis. The day after the Shields murder, Mayor Joseph Alioto met with SFPD leaders and made clear to them he no longer cared about constitutional niceties. In effect, he ordered them to do whatever it took to stop the killers. The next day, April 18, the SFPD announced “extreme measures.”

Joe Alioto (Credit Image: Gary Stevens via Wikimedia)

Effective immediately, all available officers were to patrol the streets at night in what would be one of the broadest dragnet operations in United States history. They had authorization to stop, question and search any black male who matched witness descriptions of the Zebra killers. The difficulty was that the descriptions fit nearly half the black men in San Francisco: 20 to 30 years old, or perhaps older, between five-nine and six feet, slender to medium build, light or dark, perhaps a thin mustache, or perhaps not so thin, or perhaps no mustache at all. Men not found to be suspicious were to be issued “Zebra cards,” IDs attesting that they had already been stopped. If stopped by police again, they could display the card and be waved on.

A majority of the San Francisco’s whites supported the “Zebra sweeps,” as they were called, but they proved intensely unpopular with blacks, including detectives Gilford and Sanders. Sanders recalls:

Gil tried to tell them that it would have the opposite effect from what they wanted. The odds of catching anybody would be slim to none. But it was a sure bet they would piss off the black community and alienate the very people we were trying to get to help us. And that was the best-case scenario. The worst case would be if something happened and some innocent guy got hurt by an overzealous cop. Then there was no telling where it would end. [204]

But the top brass was firm: The sweeps began on the evening of April 18, with over 100 black men stopped and searched.

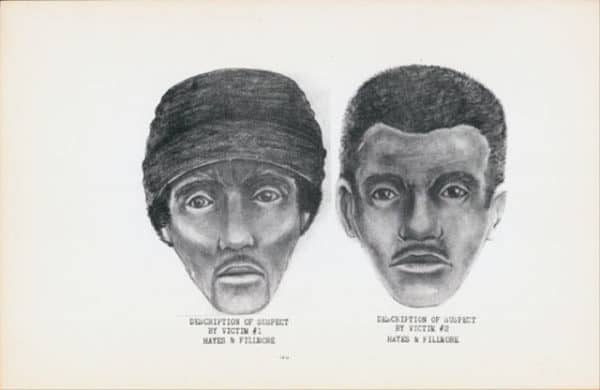

Meanwhile, Chief Investigators John Fotinos and Gus Coreris decided to work with the SFPD’s sketch artist. Normally, witnesses describe suspects directly to sketch artists. But while scores of witnesses had seen one or more of the killers, none had a clear enough recollection to feel comfortable with a sketch made from memory. Moreover, using a sketch was risky: if someone who looked nothing like the sketch was arrested, a clever defense attorney could turn it into exculpatory evidence. But after six months of dead ends, Fotinos and Coreris decided to take a chance on combining several witness descriptions themselves. The sketch appeared in both the Chronicle and the Examiner on April 18, the same day the sweeps began, and was soon visible all over the city:

Storeowners taped copies cut from newspapers onto storefront windows, and supermarkets posted them on neighborhood bulletin boards. Businessmen carried them in coat pockets to check passersby. No matter where you looked, there they were. [205]

Sketches of the murderers.

On April 19, the city announced a $30,000 “Zebra Reward” for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the killers. The announcement appeared in a brief article at the foot of the San Francisco Chronicle’s front page. That night, the sweeps were expanded to cover a wider area, and over two hundred officers were involved. The chief of police had assured the public that officers were interested only in information related to the Zebra killings, and that lesser offenses would be ignored, but Prentice Sanders remembers that this was not how things worked: “Instead of just stopping people and questioning them, they were spread-eagling them against walls and busting them for anything they found: a joint, a penknife that was too long, even unpaid traffic tickets.” [209]

Among the men stopped on that second night was a lawyer named Joseph B. Williams, who had argued many cases for the NAACP. At 62, he was more than 30 years older than the age range for the sweeps. He decided to bring a federal lawsuit against Mayor Alioto, the SFPD and the city. Hearings began almost immediately.

The ACLU, the NAACP, and the Sun-Reporter — San Francisco’s largest black newspaper — all joined in criticizing the sweeps. Alioto tried to diffuse the situation by meeting with the few prominent blacks he could find willing to support his strategy, but other blacks called them traitors and “trained seals.”

By April 21, the fourth night, as many as 350 officers were on the streets, including volunteers from other agencies and 150 reserve officers with limited training. Some detainees began retaliating. In the most serious incident, a black man walking down Haight Street was ordered to stop by a plainclothes officer. When he did not stop, the officer ran after him shouting “Stop, Police!” The man took out a pistol and fired. Several cops returned fire, hitting him six times. Amazingly, the man survived. Later on, he told Gilford and Sanders that “he took the gun because with all the talk about Zebra, he was scared of reprisals, and since the cops were in plain clothes he didn’t know whether they were really cops or just guys out to get him.” [214]

Protestors began to follow [Mayor] Alioto around, hounding him with placards that accused him of leading a race war. When that Monday [April 22] after a series of meetings on Zebra, Alioto left for a waiting limousine, protestors surrounded him, refusing to let him pass. Some shouted at him. Others spat. Then one man began beating Alioto on the head with the sign he was holding, until the mayor’s aides stepped in, helping Alioto push through the crowd to his car. One he was inside, the protestors surrounded the limousine, pounding on it as the mayor’s driver sped away. [215]

Radical organizations tried to exploit the situation. The Black Liberation Army sent out a communiqué calling for the creation of a “People’s Army” consisting of groups like themselves, the Symbionese Liberation Army, the Weather Underground, and whoever was behind Zebra.

Meanwhile, Joseph B. William’s lawsuit was making progress. When the SFPD’s chief investigator was called upon to testify, he acknowledged that the Zebra sweeps — which he had publicly supported — had failed to accomplish anything. He called them “ineffective and unproductive,” later repeating the admission to journalists. Judge Alfonso J. Zirpoli was preparing to declare the sweeps a violation of the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition against “unfair searches and seizures.”

Across the Bay in Oakland where he had moved, Anthony Harris was not earning enough to support his girlfriend and their new baby. Like everyone else in the Bay Area, he began seeing the police sketch of the Zebra suspect, and he was convinced it looked like him. The resemblance may have been accidental: Fotinos and Coreris amalgamated verbal descriptions from a number of witnesses, more of which probably referred to Larry Green, J. C. Simon and Manuel Moore than to Harris. But there was a resemblance, and Harris was afraid he wouldn’t be able to go out on the street much longer without others noticing it.

He also spotted the notice of the $30,000 “Zebra Reward” for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the killers. Maybe he could keep himself out of trouble and solve his financial difficulties at the same time.

Torn between hope and fear, he mulled the situation for a few days as Alioto’s Zebra sweeps roiled San Francisco. Finally, on Monday, April 22, at 4:30 in the afternoon, Anthony Harris picked up the telephone and dialed the San Francisco City Government.

* * *

The authorities had appealed to the public for tips, and during the period of the Zebra sweeps they got an avalanche. Virtually all were worthless, but all had to be followed up. So when the phone rang in Room 450 of the Hall of Justice, it did not provoke excitement. What’s more, unlike most callers, Harris refused to give the information he claimed to have over the telephone; he insisted officers come to see him in Oakland. The duty was given to a couple of burglary inspectors, who drove off thinking they were probably on a fool’s errand.

When Klotz and Brosch met Harris on the Oakland Parkway, where he said he would be, he was wearing a black tuxedo, tennis shoes, and a fezlike hat and acting paranoid, going on about how dangerous the guys behind Zebra were. Klotz suspected he was, in his words, a “sack of nuts.” [222]

Harris told the inspectors about meeting the killers in San Quentin, that they were all Muslim and worked at Black Self-Help Moving and Storage, which Brosch was familiar with from having recovered stolen property there. Harris was afraid they were being watched, so the inspectors took him back to the Hall of Justice to continue the interview. Not long afterwards, Gilford and Sanders arrived, and Klotz and Brosch broke off the interview to share information with them.

Both immediately recognized one of the names Harris had mentioned: Larry Green. “The moment we heard Green’s name, a kind of electric shock went through Gil and me,” Sanders recalls. “It was like all the tumblers in a lock coming together again. Harris talked about the Hagues being attacked, about Erekat, about Dancik, the five-in-one night — all of it.” [223]

Gilford called in the rest of the Zebra squad, and chief investigators Fotinos and Coreris continued the interview into the evening. What most impressed investigators was Harris’s knowledge of an incident the night before the attack on the Hagues. Jesse Cooks, Larry Green and Harris had tried to kidnap two girls and a boy in the Ingleside neighborhood. One of them pulled a gun and motioned the children towards the van, but the boy yelled, “Cops!” It distracted the would-be kidnappers long enough for the children to run away. As Sanders recalls:

Nothing about the kids in Ingleside had been printed yet in the press. The only way for Harris to know about it was to have heard it from one of the killers, or to have been there himself. That was the detail that made everyone certain he was the real deal. [225]

Harris also knew about the attacks on Saleem Erekat and Paul Dancik, but he did not know details about the shootings of December 20 (Ilario Bertuccio, Theresa DeMartini) or December 22 (Neil Moynihan, Mildred Hosler). He did explain, though, that in late December, Larry Green had asked him to help dispose of a bag that he realized from its look and smell contained a corpse: “unidentified body No. 169.” The two men took it from the Black Self-Help warehouse, carried it to Green’s van, and drove out and dumped it on Ocean Beach.

Harris claimed that there was a secretive society within the NOI called the “Death Angels.” To become a member, one had to kill either nine white men, five white women, or four white children. Membership was confirmed by presentation of lapel pins. He said Jesse Cooks was a high-ranking member of the Death Angels and that the other men involved in Zebra were primarily motivated by a desire to join. He claimed there were scores of Death Angels in other groups across the country.

These lurid claims feature prominently in popular accounts of the Zebra murders, including Clark Howard’s Zebra (1979), but there is no evidence other than Harris’s claims that there were ever any “Death Angels.” No membership pin has ever turned up, nor has any supposed member ever talked about the group as part of a plea deal. Prentice Sanders recalls: “I spent another twenty years in homicide after Zebra and about thirty more years overall on the force, and I never once heard anyone mention the group again. Not once.”

There are other grounds for treating some of Harris’s claims with caution. When he began talking to police, he did not yet have immunity from prosecution, and was trying to minimize his own guilt. By his own admission, he was at least an accessory to the attack on the Hagues. His fiancée of that time testified that he came home that night covered in blood and said he had been “out killing devils.”

In his initial statements, Harris claimed he stayed outside the store during the robbery and murder of Saleem Erekat. Later, at the trial, it emerged that he left a bloody palmprint inside the store. He explained that he had lied earlier because he was afraid his parole would be revoked.

Police ended the interview around ten o’clock and drove Harris back to Oakland. Later that night, Harris called Fotinos and Coreris, saying he had talked to Green who claimed to know about his cooperation with the police and said there was a contract on his life. Fotinos and Coreris drove back to Oakland, picked up Harris and his family, and took them to a Holliday Inn in San Francisco.

Harris’s statement was not enough to justify arrests. As an accomplice to some of the killings, all his claims had to be corroborated by another source to have the weight of proof in court. Accordingly, on April 24, two days after the first interview, police started round-the-clock surveillance on all the men Harris had named, bugging Black Self-Help. Investigators heard nothing directly incriminating, but soon learned the slang Green, Simon and Moore used to discuss their crimes: Going “rolling” meant driving around looking for victims to attack, while to “sting” meant to carry out an attack.

On April 25, bowing to mounting public and legal pressure, Mayor Joseph Alioto ended the Zebra sweeps after seven days. Alioto does not seem to have known of Harris’s statement, so he did not realize how close police were to solving the case.

Harris wandered off more than once over the days and weeks that followed, eluding his guards and disappearing sometimes for days at a time before calling in and again asking for protection. On one occasion, he visited Larry Green’s family in Berkeley, hoping they might be able to talk their son into confessing. Harris’s girlfriend told another woman where they were staying, and word quickly got out. NOI members showed up in the lobby of the Holiday Inn, and police had to move the family again.

On April 27, when Klotz and Brosch went to pick up Harris after one of his escapades, he said he would not cooperate further unless he could talk to the mayor, who was in Southern California that day. Gus Coreris called Alioto and told him about Harris. The mayor returned to San Francisco that night, and met with Anthony Harris at 3:30 AM, April 28. Harris told him his story and asked for immunity. Alioto had one reservation:

Being an accessory to murder is one thing; being a murderer is another. He would not grant immunity to anyone who had actually killed someone. Harris, as he had insisted all long, assured Alioto that he had not. With that, the deal was done. Immunity was his, and the reward would be as well, if his evidence led to a conviction. [233]

Later that day, an officer visited Richard Hague. He was in the hospital, preparing for yet another surgery for his wounds of six months earlier. Shown pictures of a dozen or so black men, he unhesitatingly picked out three: “Him, him, and him.” The pictures were of Jesse Cooks, Larry Green and Anthony Harris.

Mayor Alioto was elated and wanted to call a press conference. Investigators argued against it: They were still seeking corroboration on at least six other men Harris had named, including J. C. Simon and Manuel Moore. This is a common problem in serial crimes: Investigators want to postpone arrests until they have more evidence against suspects. However, the surveillance team was picking up more talk about “rolling,” and no one wanted to wait until more innocents were killed.

Alioto called a press conference the next morning, April 29. He told reporters everything he thought he knew about Zebra, and a great deal else besides. The mayor claimed that more than 80 killings all over California since 1971 might all be linked to Zebra and NOI. Much of this was pure speculation and remains controversial to this day.

The police on the case were frustrated by Alioto’s announcement. As Sanders recalls:

The guys on surveillance felt sure we could have had the goods on everyone Harris named if they were given more time. The Zebra squad was part of the group that kept tabs on the building where Larry Green and J. C. Simon lived during those final days, and Gil and I felt the same way. It didn’t seem to matter to them that Harris had gone to the cops. But when Alioto went public, everything changed. There was a price to be paid by going public that soon. [236]

For two days, controversy over the mayor’s claims raged as the Zebra task force prepared for a massive operation in the early hours of May 1. As Sanders remembers the events:

It felt like the night before D-Day. There were seven suspects, and they were spread out all the way down to San Jose. Plus we had Black Self-Help to go into, secure, and try to collect whatever evidence we could. We had to do it fast, to make sure no one got wind of what was going down and took off on the run. On top of everything else, Harris had said that there was no way these guys would be taken alive. [237—238]

In the event, the raids went smoothly, with none of the suspects resisting arrest. Surviving Zebra victims positively identified three of the seven men: Larry Green, J. C. Simon and Manuel Moore. This was crucial because the police had enough corroborating evidence (from Richard Hague) to justify arresting only one new suspect: Larry Green.

The other four whom Harris claimed were part of the conspiracy had to be released. It is possible they were guilty of something, but the SFPD continued surveillance for several months and never heard another word about “rolling” or “stings.” None of the four men released was ever charged with any crime related to Zebra, and once Green, Simon and Moore were off the streets, the killings stopped.

At nine o’clock that same evening, however, there was a grim postscript to the Zebra murders. A young black man named Theodore Gooden was driving east through the city’s Broadway Tunnel; next to him sat army medic James Cook, also black. Two white men in a pickup pulled up alongside them on the right. The man in the pickup’s passenger seat leaned across the driver and fired a gun three times into Gooden’s car, killing Cook and striking Gooden in the hand. The driver of the pickup then sped off into the night.

The killers were never caught, so there can be no direct proof, but this could have been the long-feared retaliation for the Zebra murders. Ironically, the Zebra killers had already been in custody for over 12 hours. This final shooting supports Mayor Alioto’s decision not to wait any longer before ordering arrests.

* * *

Larry Green, J. C. Simon, Manuel Moore and the already incarcerated Jesse Lee Cooks were soon indicted on a slew of charges relating to the 15 fatal and seven non-fatal victims of the Zebra attacks. The trial got underway in March 1975 and lasted for over a year, producing a transcript of more than 40,000 pages. Anthony Harris kept disappearing:

He disappeared so often that eventually he had to be kept in protective custody so rigorous it was prisonlike. One particularly unnerving pretrial twist for the prosecution came when he wrote a letter recanting all the claims he had made about Zebra and mailed it to everyone from President Ford to Minister John Muhammad of Temple No. 26. Harris subsequently recanted his recantation, claiming the reason he had written the letter was that he had not yet been given an attorney to represent him. Once his complaint was addressed, Harris reaffirmed his original statements, and the prosecution was able to resume building its case. [252]

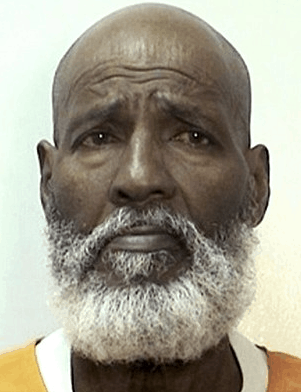

J. C. Simons’s behavior led some to wonder about his sanity. Under cross-examination he claimed to have travelled from Texas to California by riding a snake halfway and a tornado the rest. Asked about a binder he had when he was arrested, containing NOI Lesson No. 10 on “killing devils,” he claimed that Allah had handed it to him at a public park in San Francisco.

In March 1976, a jury found the defendants guilty on all counts. All the men received multiple life sentences and none has ever been paroled. J. C. Simon died in 2015, aged 69. Manuel Moore died in 2017, aged 75. Jesse Cooks and Larry Green are still serving their sentences. Anthony Harris received his promised $30,000 reward after the convictions, and may have been given a new identity to protect him. Once again, however, he disappeared, and his later fate is unknown.

J. C. Simon, age 69, shortly before his death.

Investigating Officer Prentice Earl Sanders went on to serve a term as police chief of San Francisco. In 2011, his memoirs of the killings (written in collaboration with Bennett Cohen) were published as The Zebra Murders: A Season of Killing, Racial Madness, and Civil Rights. All page references in this article are to that book unless specifically identified as from Clark Howard’s older and better-known work, Zebra: The True Account of the 179 Days of Terror in San Francisco (1979).

The Zebra victims never became the object of a cult, as many blacks — some not even “victims” in any ordinary sense — have become. But the increasing confidence with which whites are publicly vilified may hint of future horrors that could resemble what San Francisco went through in 1973–74. Once people have been demonized, the idea of “killing devils” cannot be far behind.