Reckoning Without Race

Raymond Wolters, American Renaissance, May 18, 2018

Gene Dattel, Reckoning with Race: America’s Failure, Encounter Books, 2017, 352 pp., $27.99.

Gene Dattel is a white man who was born and reared in a majority-black cotton county in Mississippi. He attended Yale University and Vanderbilt School of Law, and then worked for 20 years at Solomon Brothers and Morgan Stanley.

Mr. Dattel’s first book, The Sun That Never Rose (1994), described Japan’s structural economic problems at a time when many analysts thought the Japanese economy was an unstoppable juggernaut. In his most recent book, Reckoning with Race: America’s Failure (2017), Mr. Dattel attributes America’s current racial problems to the disproportionate failure of blacks to assimilate the mores and standards of American whites. Rather than place most of the blame on blacks, however, Mr. Dattel maintains that whites are primarily responsible for this failure.

As a boy growing up in the Mississippi Delta, young Mr. Dattel noted that a disproportionate number of blacks worked in the cotton fields, while most whites had other work. More recently, racial separation has continued, with most blacks living in predominantly black areas and most whites living among whites. According to Mr. Dattel, this separation explains black failure to assimilate mainstream American values. He is especially worried by black deviation from mainstream values with respect to marriage and the family.

This emphasis on the importance of integration was presaged as far back as 1954 when Harvard psychologist Gordon W. Allport published an influential book, The Nature of Prejudice. Allport held that members of different races would become friendly and assimilate if they mingled, but he warned that mingling must be between groups of “equal status.” Allport predicted that race relations would deteriorate if — as Mr. Dattel recommends — middle- and upper-class whites were forced to accept large numbers of lower-class blacks in their schools and places of business.

In 1964, another professor, James S. Coleman, then at Johns Hopkins University, produced an especially influential report, “Equality of Educational Opportunity.” He noted that black students who attended predominantly white schools got better grades than blacks who attended mostly-black schools. Coleman went on to become one of the most influential advocates of court-ordered busing for racial balance. Like Mr. Dattel today, Coleman thought racial mingling was the best way to teach mainstream values to blacks.

Later, however, Coleman came to believe that busing-for-racial-balance was wrong. He acknowledged that his earlier report had failed to recognize that the higher-scoring black youngsters who had attended predominantly white schools in the 1950s and 1960s were not representative; they were either the children of well-to-do blacks who lived in predominantly white neighborhoods or highly motivated students who volunteered to take long bus rides to get to a better school.

In the mid-1970s, Coleman withdrew his earlier support for court-ordered busing. He said that once black enrollment reached a “tipping point,” many whites would leave integrated schools. Speaking informally to a news reporter, Coleman said the departures stemmed from “the degree of disorder and the degree to which schools . . . have failed to control lower-class black children.” It was “quite understandable,” he said, for middle-class families “not to want to send their children to schools where 90 percent of the time is spent not on instruction but on discipline.” Mr. Dattel does not mention the work of Professors Allport and Coleman. He simply repeats his main theme: that massive integration is the best way to ensure that blacks adopt mainstream values.

Mr. Dattel knows a great deal about the history of race relations and the American economy. He argues that slavery was on the road to extinction when George Washington was inaugurated in 1789. There were only 700,000 slaves in the United States, and most were producing tobacco, indigo, sugar, and rice — crops that had a dark future because of competition from the Caribbean. But when Eli Whitney invented (or perfected) the cotton gin, English textile mills developed an insatiable appetite for American cotton. Consequently, by the time Abraham Lincoln was elected President in 1860, the number of black slaves had increased to more than four million. Cotton accounted for 60 percent of all American exports, and continued to reign as the single most valuable export until 1937.

(Credit Image: © Peggy Peattie/ZUMAPRESS.com)

In addition to fostering the growth of slavery and the economy, the cultivation of cotton also fostered racial separation. In many counties, most blacks hoed and picked cotton, while most whites had other jobs. After Emancipation, this separation became a formal system of segregation that, according to Mr. Dattel, prevented blacks from assimilating mainstream white culture.

Mr. Dattel notes that some blacks and many well-intentioned whites believed the freed former slaves should be resettled elsewhere. This was the goal of the American Colonization Society, whose members constituted a who’s who of antebellum America: James Madison, James Monroe, Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Andrew Jackson, and many more. Their purpose was to establish a home for freed slaves in Liberia.

During the Civil War, many influential abolitionists and anti-slavery leaders favored colonization. One was Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Another was President Lincoln, who asked an African American delegation, in 1862, “Why should the people of your race be colonized?” He answered his own question: “You and we are different races. . . . You suffer very greatly by living among us while we suffer from your presence.” Lincoln told another group of emancipated blacks, “There is an unwillingness on the part of our people, harsh as it may be, for you free colored people to remain with us.”

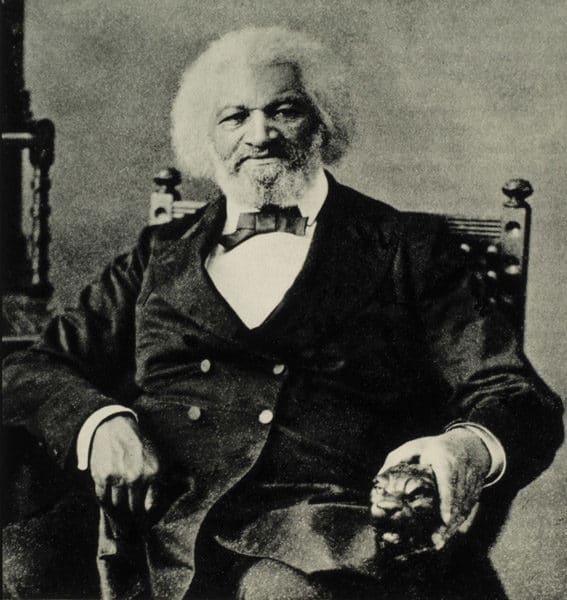

Mr. Dattel notes that after the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of the Civil War, many prominent Americans continued to explore the possibility of black emigration. In 1871, for example, General Benjamin Wade, an abolitionist Republican, traveled to Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) with America’s most prominent black, Frederick Douglass to explore the possibility of annexing Santo Domingo as a home for freed slaves. The negotiations failed, however, in large part because black workers were needed in the South to satisfy the demand for cotton.

Frederick Douglass (Credit Image: © Glasshouse/ZUMAPRESS.com)

Mr. Dattel also notes that the vast majority of blacks stayed in the South until white workers leaving for military service during the First World War caused labor shortages in the North. Northern employers then encouraged blacks to fill the vacancies, and about one million Southern black workers moved to the North — a phenomenon that often is called “The Great Migration.” The same pattern recurred, in even greater numbers, during and after the Second World War. Then, during the second half of the twentieth century, Mr. Dattell writes, “the full implementation of farm machinery and chemicals finally displaced the blacks in the cotton fields.”

Most Northern whites accepted blacks at work but opposed social mixing. They steered blacks into black neighborhoods, and, as a great deal of research on “white flight” has shown, they fled from communities and schools that accommodated more than a small minority of blacks.

This white flight bothers Mr. Dattel. He criticizes “unenlightened” whites for their “all-consuming fear” of racial integration. He pays no heed to evidence that white fear was not irrational; that it was a reaction to a pattern of decline and decay that accompanied integration again and again.

Like most historians, social scientists, public leaders, and mainstream journalists, Mr. Dattel adheres to the Standard Social Science Model. He believes that “history” and “culture” account for any disparities in the way different groups behave. Nowadays, as University of Iowa historian Marshall Poe has noted, DNA researchers are “talking about intelligence, temperament, and a host of other traits.” They are saying that “the races . . . are differently abled in ways that really matter.” But Mr. Dattel sticks to the dogma that history and culture alone are responsible for group differences in behavior.

Mr. Dattel, however, does not give blacks a free pass. He thinks that in modern America blacks themselves are responsible, in large part, for their plight. He believes civil rights legislation has removed the major external barriers to upward mobility. He notes that educators and employers have gone beyond “non-discrimination” and have established thinly disguised racial preferences that are intended primarily to benefit blacks. He notes that America has declared war on “microaggressions” that allegedly have so traumatized blacks that they have not been able to take advantage of their opportunities. He dismisses the impact of “systemic racism,” “implicit bias,” and “stereotype threat,” and opposes yet more assistance in the form of a New Marshall Plan or expensive “school reform.” Instead, Mr. Dattel reports that “trillions of dollars” have already been wasted in a futile effort to assuage various “grievances” and close the racial gap in test scores. Instead, Mr. Dattel recommends massive integration as the sine qua non for spreading mainstream American values into the black community.

Mr. Dattel also argues that it is time for “a serious effort to change the elements of black culture.” Blacks should work to solve a “fundamental problem” that the black sociologist E. Franklin Frazier wrote about for decades: “the inability of the black male to enter the economic mainstream, which in turn prevented his ability to be a father and husband, which in turn prevented a stable family structure.” Mr. Dattel believes that thorough racial integration will solve all these problems.

Mr. Dattell writes clearly and has an appealing presentation. But there is unconscious irony in the title of his book, Reckoning with Race. Mr. Dattel does not reckon with race. He does not even consider the possibility that Mother Nature, not racial segregation, causes racial differences in behavior, success, and failure.