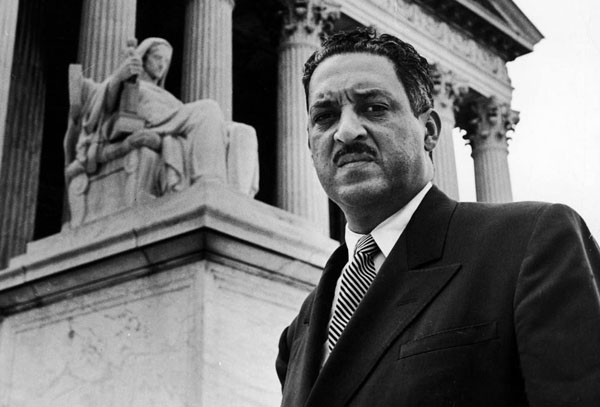

“A Race Man,” First and Last

Raymond Wolters, American Renaissance, November 27, 2015

Will Haygood, Showdown: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court Nomination that Changed America, Alfred A. Knopf, 2015, 404 pp., $32.50.

Showdown is an interesting biographical study of Thurgood Marshall. Its special emphasis is on the summer of 1967, when the United States Senate approved President Lyndon B. Johnson’s nomination of Marshall as Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. The black author, Will Haygood, knows how to tell a good story. One of his previous books, The Butler: A Witness to History, was translated into a dozen languages and was the basis for an award-winning motion picture, The Butler. But Mr. Haygood’s unusual method of presentation, which he calls “nonlinear narrative,” is not a success. He uses this method to construct a questionable narrative that converts the story of Marshall’s confirmation into a diatribe against Southerners and strict constructionists.

Mr. Haygood begins with a lively account of Marshall’s life before his appointment to the high court. He adds little to what earlier biographers have written, but this sets the stage for what will come. Marshall was born in Baltimore in 1908, the second son of a lower-middle-class family. His mother was a stay-at-home mom, and his father worked for a while as a waiter on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and later as a steward at the exclusive Gibson Island Club. As a teenager, Marshall attended the Colored High and Training School in Baltimore, where he eschewed sports and instead became one of the school’s star debaters.

At age 17, he enrolled at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, where all the students were black and all the professors were white. At that time whites had the Ivy League, and blacks had their own “Black Ivy League,” of Fisk, Howard, and Lincoln. Lincoln was known as “the Black Princeton.” At Lincoln, Marshall joined the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity for social life, and he became friendly with a fellow freshman, Langston Hughes.

As in high school, Marshall gained campus-wide recognition as a member of Lincoln’s nationally-known debate team. In 1927, Marshall and his teammates were applauded for their performance against a team from Penn State in a debate on the value of the National Prohibition Act, better known as the Volstead Act. The following year, Marshall’s team traveled to Harvard, where they debated the question: “Resolved: That Further Intermixture of Races in the United States is Desirable.” The Ku Klux Klan was opposed to debating this question, and bricks were thrown through the window of the Liberal Club, where the debate took place. As was the general practice, the teams had to draw straws to decide whether they would support or oppose the resolution. As it happened, Marshall and his teammates were given the task of arguing against race mixing.

Shortly after he graduated from Lincoln in 1929, the 21-year-old Marshall married Vivian “Buster” Burrey, a black University of Pennsylvania student who came from a family of means. Then, in 1930, Marshall entered Howard University Law School, where a new dean, Charles Hamilton Houston, placed special emphasis on training black lawyers to work for the rights and interests of blacks. This, Marshall decided, “was what I wanted to do for as long as I lived.” Under Houston’s tutelage, Marshall became what blacks of the 1930s admiringly called “a race man:” a black man whose major work was to advance the interests of his race.

In 1934, one year after graduating from Howard, Marshall went to work for the NAACP. One of his first assignments was to travel through the South gathering information on “separate but equal” public schools. Thanks to his modest NAACP salary he was also able to offer free legal services for blacks. Marshall often stayed with his black clients, “and he often asked the male members of those households if they had their shotguns ready for protection.” In Columbia, South Carolina, Marshall barely escaped being lynched. In Gadsden County, Florida, a home where Marshall had stayed was dynamited, and the homeowners, Harry and Henriette Moore, were killed.

Marshall showed extraordinary bravery as he roamed through the South arguing for black clients. He also amassed an impressive number of landmark victories in the Supreme Court. In 1944, there was Smith v. Allwright, in which Marshall persuaded the Court to outlaw the all-white Democratic primary in Texas. In Shelly v. Kramer (1948), the Court ruled it was illegal to bar blacks and other minorities from purchasing property, even if there was a restrictive covenant in a homeowners’ deed. In 1950, in Sweatt v. Painter, Marshall won an order requiring the University of Texas to admit a black it had previously barred from its law school.

In 1954 Marshall won his most consequential case, Brown v. Topeka Board of Education, in which he persuaded the Supreme Court to rule that public schools must admit students on a racially nondiscriminatory basis. Altogether, Marshall appeared 34 times as an advocate before the Supreme Court, and he won 29 of his cases. It is hard to dispute Mr. Haygood’s conclusion: “There was not another lawyer in America whose constitutional victories could match Thurgood Marshall’s . . . .” “No [other] Justice had come to the high court with the background he possessed in traveling the land and fighting from courthouse to courthouse . . . He was a colossal figure in American jurisprudence.”

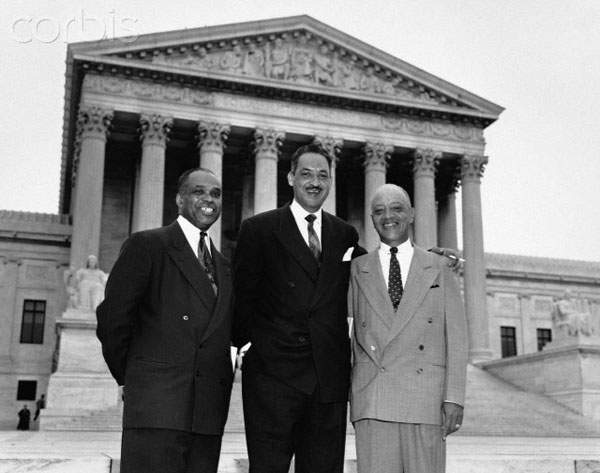

George Hayes, Thurgood Marshall, and James Nabrit, Jr. after their victory in Brown v. Board of Education.

Nevertheless, most Southern senators thought Marshall was a poor choice for appointment to the high court. They said Marshall’s disposition was suitable for an advocate but not for a magistrate. They also criticized Marshall’s legal philosophy, which Mr. Haygood summarizes as a “decades-long [and often-expressed] belief that the Constitution was a living document.”

North Carolina’s Senator Sam Ervin maintained that Marshall was “by practice and philosophy a legal and judicial activist.” Ervin further predicted that if Marshall were appointed to the Supreme Court he would join other activist justices in rendering decisions which would “substantially impair, if not destroy, the right of Americans for years to come to have the Government of the United States and the several states conducted in accordance with the Constitution.” Ervin professed that he had “no prejudice in my mind or heart against any man because of his race.” Ervin recognized, however, that in opposing Marshall’s nomination, he was laying himself “open to the easy, but false, charge that I am a racist . . . .“

Showdown is testimony to the truth of Ervin’s observation. Mr. Haygood searched for evidence of Ervin’s racism, but the most damning thing he could find was Ervin’s signature on the Southern Manifesto of 1954: a document that said the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board was “unwarranted” and that urged resistance to “forced integration by any lawful means.” Since this did not prove that Ervin was a racist, Mr. Haygood deployed his peculiar method, “nonlinear narrative.” In doing so, Mr. Haygood describes several instances that had little to do with Marshall but which Mr. Haygood offers as evidence that Southern opposition to Marshall’s elevation to the Supreme Court grew out of deep-seated racial bigotry.

Thus, Mr. Haygood devotes several pages in one chapter to the 1934 lynching of Claude Neale, a Florida laborer who (perhaps under duress) confessed to the rape and murder of a 19-year-old white girl. Another chapter tells of the 1904 lynching of Luther Holbert, a plantation worker who fled after killing the uncle of Mississippi Senator John Eastland. Senator Eastland’s father tracked Holbert down, tied him to a tree, and set the tree on fire. Mr. Haygood also devotes an entire chapter to Southern white opposition to the 1916 appointment of a Jew, Louis Brandeis, to the U. S. Supreme Court; and several pages to the 1915 lynching of another Jew, Leo Frank, who had been in prison after being convicted of the murder of a 13-year-old white girl. Another chapter condemns President Theodore Roosevelt for not considering the provocations that black soldiers had experienced in an incident in which they fired some 200 rounds in Brownsville, Texas, in 1906 (but killed only a white bartender and wounded one white police officer). Mr. Haygood also criticizes President Woodrow Wilson for similarly making light of provocations that, in 1917, prompted 120 black soldiers to stage a mutiny and shoot up Houston, Texas, in a spree that claimed the lives of 15 whites, two of whom were soldiers.

For Mr. Haygood, these and several other “nonlinear narratives” are not digressions by a garrulous raconteur. They are presented as the key to understanding why most Southern Senators opposed Thurgood Marshall’s appointment to the Supreme Court. According to Mr. Haygood, “No one in the hearing room” believed South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond “for a minute when he started talking about states’ rights and how he was trying to stop the encroachment of federal power. They thought it pure racist code.”

Mr. Haygood to the contrary notwithstanding, Southerners and other strict constructionist Senators–especially Sam Ervin and Strom Thurmond–raised several points that deserved respectful consideration. Ervin, for example, questioned Marshall’s temperament. He conceded that Marshall was one of the nation’s leading advocates; that Marshall had a distinguished career; and that Marshall had ably pleaded the cases and the cause of his clients and his people. But Ervin doubted that Marshall had a judicial disposition. According to Ervin, “in passing upon the qualifications of an appointee to the Supreme Court, it is not only important for a Senator to determine whether the nominee has sufficient knowledge of the law or sufficient legal experience, but also to determine whether he is able and willing to exercise that judicial self-restraint which is implicit in the judicial process.” Quoting Daniel Webster, Ervin declared: “It is hardly too strong to say that the Constitution was made to guard the people against the dangers of good intentions. There are men in all ages who mean to govern well, but they mean to govern. They promise to be good masters, but they mean to be masters.” According to Ervin, the Justices of the Supreme Court should “place themselves as nearly as possible in the position of the men who framed [the Constitution].” Their role was “simply to ascertain and give effect to the intent of the framers . . . .” For Ervin, the greatest judicial virtue was “the virtue of self-restraint.”

Marshall, on the other hand, had repeatedly said the Constitution should be interpreted as “a living document,” and he did not back away from this point of view during his confirmation hearing, in which he said the nation’s charter should be interpreted in the light of current problems. Like a predecessor-Justice, Robert Jackson, Marshall believed the Constitution contained “majestic generalities” that should be construed in the light of current needs. Like his soon-to-be fellow justice, William Brennan, Marshall thought the genius of the Constitution rested “not in any static meaning it might have had in a world that is dead and gone, but in the adaptability of its great principles to cope with current problems . . . .”

Marshall’s critics, on the other hand, rejected the idea that justices could change the interpretation of a Constitutional provision and give it another meaning. According to Ervin, that theory did not mean that the Constitution was “living” but rather that it was “dead.” Americans were being ruled by “the personal notions of the temporary occupants of the Supreme Court.”

Marshall’s partisans prevailed. In 1967 the Senate confirmed his appointment to the Supreme Court. The vote was 9-6 in the Judiciary Committee and 69-11 (with 20 abstentions) in the full Senate.

Mr. Haygood misses the mark when he dismisses strict construction as “pure racist code.” He is also mistaken when he fails to recognize that, all along, Marshall had been a race man, committed to advancing the interests of blacks. In the 1950s, in testimony before the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board, Marshall and his chief assistant, Robert Carter, had said it was their “dedicated belief” that the Constitution was “color-blind.” They said they were “not asking for affirmative relief. . . . The only thing that we ask for is that the state-imposed racial segregation be taken off, and to leave the county school board . . . to assign children on any reasonable basis they want to assign them on. . . . What we want from this Court is the striking down of race . . . . [D]o not put in race or color as a factor.”

But times change. Affirmative action for blacks came into fashion in the 1970s, and whites began to insist that the Constitution was “color blind” and that students should be admitted to selective programs on the basis of personal qualities, not race. When the issue came before the Supreme Court, however, Marshall favored discrimination to promote the interests of blacks.

One of the first Supreme Court cases on this question involved Marco DeFunis, a white applicant who filed an appeal after he learned that the law school at the University of Washington admitted black students whose qualifications were inferior to those of white applicants who were denied admission. When the justices of the Supreme Court discussed the case, it was clear that Thurgood Marshall no longer believed the Constitution was “color blind.” He was no longer opposed to preferring some students for racial reasons. “Why the turnaround?” asked Justice William O. Douglas. Marshall gave a straightforward answer: “You [white] guys have been practicing discrimination for years. Now it’s our turn.”

Haygood does not discuss Marshall’s record as a Supreme Court Justice. After the DeFunis case, however, Marshall consistently plumped for affirmative action to help blacks. His greatest triumph came in Griggs v. Duke Power Company (1971) and other cases, in which he persuaded the Court to interpret laws against “discrimination” as laws that forbade any policy, test, or standard that affected blacks adversely. Thanks to Marshall, “no discrimination” came to mean “no disparate impact.” On the surface this seems inconsistent with Marshall’s plea in Brown v. Board–“What we want from this Court is the striking down of race . . . . [D]o not put in race or color as a factor.” But to say that Marshall was inconsistent is to misunderstand him. He was “a race man.” He was consistently for his race, first and last.