The George Kennan Diaries

Jon Harrison Sims, American Renaissance, June 16, 2014

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

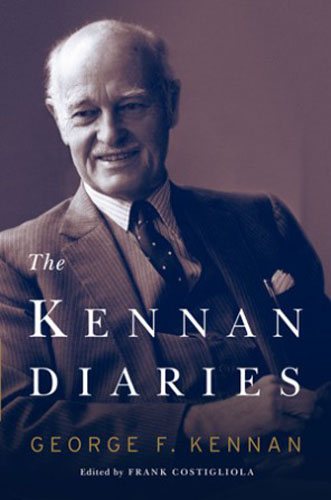

The Kennan Diaries, Frank Costigliola (ed.), W.W. Norton, 2014, 712 pp., $39.95.

The recent publication of a one-volume selection from the extensive diaries of the late George Kennan–he died in 2005 at the age of 102–has elicited cries of “racism” and “bigotry” from mainstream reviewers. They were shocked to discover that Kennan had long opposed large-scale, non-white immigration into the United States, and did not believe that racial and cultural diversity was a good thing.

If any of these reviewers had bothered to read his books, they would have known this long ago, and if they had the slightest awareness of how Americans who live outside the capitals of entertainment, finance, and politics think, they would have known that his views are widely shared. Furthermore, those who have read his memoirs and essays know that if his advice had been followed the US would not now be a declining imperial power, nor would its demographic profile increasingly resemble that of Latin America.

George Frost Kennan was the wisest of the American leaders who formulated the post World War II foreign and defense policies. A native Midwesterner of Scots and Scots-Irish heritage, he was educated at Princeton University in the early 1920s. He entered the Foreign Service after graduation and was posted to embassies and consulates in Switzerland, Germany, and the Baltic states before being sent to Berlin in 1929 for intensive training in Russian. By the time he was appointed diplomatic secretary in Moscow in 1933, he was also fluent in French and German. Although he would serve in other capitals–Prague, Berlin, Lisbon–his special area of expertise would always be Russia.

Kennan was a brilliant strategic thinker who never forgot that his duty as a diplomat and foreign policy adviser was to represent the interests of the United States. Yet he was far from being an insular American. His long service in Europe and his historical and literary interests gave him a deep and abiding love for what he called “the Northern Atlantic world” that stretched from the American Midwest across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe. This was the heart of the West, the homeland of the white race to which he belonged by birth and to which he always remained loyal.

Thus his American patriotism was always part of a broader conception of the unity of Europeans, whom he always considered to be “his people.” He called the two world wars tragic mistakes, opposed a vindictive policy toward Germany after 1945, and as early as the mid-1950s supported a policy of détente with the Soviet Union. He considered Russia to be, for the most part, a Western country, and he foresaw that communism would not last. He fully agreed with his friend, the historian John Lukacs, who wrote in 1961 that “the most important fact in the second half of the century may be that, after all, the Russians are white.”

Father of containment

It was while serving in Moscow from 1944–46 as the chief counselor to the US ambassador that George Kennan wrote the now famous “Long Telegram” of February 1946. The war in Europe had ended only nine months before, and most people still believed Russo-American cooperation would continue. Not Kennan. In the telegram, he warned the Truman administration that its wartime ally was a potential adversary bent on expanding its sphere of control. As a result, the US government should use military, political, and economic pressure to contain Soviet power and influence. His telegram appears to have been read by everyone, including the Secretary of State, who promptly brought him back to Washington to make him head of a newly created advisory body within the State Department, the Policy and Planning Staff, which he lead from 1947–49.

These were the years when the foundations were laid for the postwar strategy of the United States toward the Soviet Union–the policy known as containment. However, already by the late 1940s, Kennan worried that his superiors were exaggerating Soviet military capabilities and aggressive intentions, and were treating every part of the world as if it were of equal strategic importance. He opposed military intervention in Vietnam, for example, because he did not think Southeast Asia was important enough to justify a war to prevent the unification of Vietnam under a Marxist-nationalist government. He was right.

Strategic critic of American foreign policy

When the new Republican administration of Eisenhower came in, Kennan resigned from the State Department, and through the 1980s was attached to Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study. He wrote award-winning books on diplomatic history, and US foreign and defense policy. Republicans accused him of being soft on communism and an advocate of appeasement. In 1957, in a series of lectures broadcast on the BBC, Kennan called for rapprochement with the Soviet Union because, in the wake of Stalin’s death, he thought the new Soviet leaders might be willing to negotiate an end to the Cold War. He proposed that the US offer to withdraw its troops from West Germany if the Soviets withdrew theirs from East Germany. Germany would then be reunified but as a neutral country belonging neither to NATO nor the Warsaw Pact. American and British leaders rejected the idea as unrealistic and dangerous–but was it?

There is evidence that Soviet leaders after Stalin no longer believed in world revolution and were more concerned with maintaining power internally. Nikita Khrushchev visited Paris in March 1960 and met Charles de Gaulle. At one point, in a reference to the problems the Soviets were having with their internal Asiatic populations and with the Chinese, he moved close to de Gaulle and said confidentially, “We are white, you French and us.” De Gaulle’s reply has not been recorded.

During a 1979 summit meeting with newly elected British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Chairman Leonid Brezhnev, Thatcher said she saw no reason why their two countries could not have better relations. Mr. Brezhnev agreed, but went further: “Madame, there is only one important question facing us, and that is the question whether the white race will survive.” Mrs. Thatcher was so taken aback that she immediately left the room. Kennan would not have been shocked, as he was increasingly making the same point to whoever would listen: The greatest dangers the West faced were accidental nuclear war and overpopulation by Third-World immigration.

Kennan is known as a realist who did not believe in idealistic schemes to make the world a better place. He believed that the sole purpose of foreign policy was to promote the interests of the American nation. It was not to wage crusades abroad, to feed the hungry, heal the sick, build bridges and roads–much less to welcome the world’s misery and ethnic chaos to our shores. He consistently opposed foreign aid. It would be far better, he argued, simply to let young nations work things out for themselves.

As he wrote in his diary:

The maw into which our favors and concessions and acts of generosity are entering is bottomless. These people can consume an infinite number of our kindnesses just as they can consume infinite quantities of our material goods, and when all is said and done, there will be no more to show for the one than for the other. On the contrary, favors and kindnesses will be normally hailed as evidence of our weakness, our dependence, and our ignominy, and exploited as proof of the cleverness of those who succeeded in extorting all this beneficence out of the silly Americans. The main psychological effect of our pressing various forms of aid on individual governments will be . . . to convince the peoples generally in that part of the world that in addition to being white and imperialist we are stupid, uncertain, weak, and obviously on the skids of history, and that they are more important than anyone ever told them they were.

Africans, he wrote in 1967, “took our aid as a sign of weakness and assumed that it was given for ulterior motives, out of fear that they lean toward the Russians or the Chinese.”

Nor was Kennan under any illusions about South Africa. When Nelson Mandela was released, he wrote:

I know nothing about Mr. Mandela, other than he has been imprisoned for a very long time and resolutely refused to abandon the use of violence to obtain for his movement the power he would it to have. I know of no pearls of wisdom that have fallen from his lips, or of any other evidences of great nobility or high statesmanlike qualities on his part. That he is better off, from everyone’s standpoint, outside of prison than in it I have no doubt. That he will be brought to Washington, permitted to address the Congress, and given an ovation by people who know nothing about him but want to curry political favor with black voters, is obvious and of little importance, just another manifestation of American domestic political posturing . . . .

Kennan did not expect much from black rule:

I have no confidence in the prospects for anything like a mingling of the races in South Africa, nor can I permit myself to hope that the whites will be permitted to retain very much of the quality of their own lives, or indeed of the vitality of the economy, in a country dominated, on the principle of one-man, one-vote, by a large African majority. I would expect to see within five or ten years’ time only desperate attempts at emigration on the parts of the whites, and strident appeals for American help from an African regime unable to feed its own people from the resources of a ruined economy.

As early as 1952, Kennan understood something that baffled his colleagues: the intense anti-American sentiment in Asia. American policy-makers thought the solution was trade and assistance, but Kennan disagreed. Nothing can be done, he wrote, because “what is eating at the hearts of so many of our Asian friends is really the question of status, aggravated by a burning sense of inferiority and jealousy of us for our riches and for the relative security of our position.” He understood that for Asians, to express gratitude would be to acknowledge inferiority.

In the Middle East, Kennan wanted the West to maintain control of strategic points and resources, such as the Suez Canal and the Arabian oil fields:

The Western world has no need to be apologetic about the minimum facilities and privileges it requires in the Middle East. Most of these have already been in existence for long periods of time, and there has grown up around them a right of usage.

It was Western capital and technology that had built the Suez Canal, discovered oil, and developed the means to extract it. What right did the Egyptians, the Saudis, or the Iranians have to claim the fruits of Western science and organization simply because they happened to live nearby? All his life Mr. Kennan would recur to the folly of “tolerating the nationalization of the oil fields, giving the status of sovereignty to the various sheikdoms, and then permitting ourselves and our allies to become dependent on their oil.”

In 1956, the new president-dictator of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser, announced the nationalization of the Suez Canal. The British and French governments decided to recapture the canal and overthrow Nasser. They developed a brilliant plan and enlisted Israeli support. Soon after the operation began, however, the Eisenhower administration forced the French and British to pull back.

Kennan was appalled, but not surprised: “This I thought it likely we would do, since no one in authority in Washington cared anything about those [French and British] interests, or realized that they were ours as well.” American leaders seemed to think it was more important to appease Third-World opinion than to stand by their European allies:

The Arabs are smiling at us and we are permitted to bask, briefly, in what seems to be what the American political mentality has always yearned for: the approval and admiration and gratitude of the little nations for our support to them in the face of the greedy depredations of the great imperialist powers.

Kennan assumed, correctly, that gratitude would not last long.

So long as Europeans controlled Suez and the oil fields, they could leave the natives to their bloody ethnic and sectarian feuds. “Let us not deceive ourselves into believing that the fanatical local chauvinisms represent a force that can be made friendly or dependable from our point of view,” he wrote. On the contrary, “these chauvinistic movements, permeated as they are by violence and immaturity, will breed bloodshed, horror, hatred and political oppression worse than anything we see today.”

Americans still think they can tame “fanatical local chauvinisms” in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Syria; instead, we have only stoked raging anti-Americanism.

Immigration

The same desire to win the hearts and minds of brown people was behind the overthrow of our immigration laws in 1965. American leaders believed that restrictions on non-European immigration offended non-whites, and harmed American chances of gaining Cold War allies among the newly independent countries.

Kennan’s diaries do not include any reference to the law, and indeed few Americans seem to have noticed that Congress had changed immigration in a fundamental way. The first reference to the effect of this legislation I can find in Kennan’s published writing is from his 1968 essay, “America after Vietnam,” in which he warned of the long-term effects of “the immigration of great masses of people reared in quite different climates of political and ethical principle.” The first reference in the diary is from 1978, during a visit to Southern California, in which he expressed regret that “people of British origin . . . are not only a dwindling but a disintegrating minority.”

Kennan saw the false promise of “multi-culturalism” before the term was even invented:

The Latin, Levantine, African, and Oriental elements that now make up so large a part of this population: they too are destined, for the most part, to lose their character, their traditions, their unique coloration, and to melt into a vast polyglot mass, devoid of all three things: a sea of helpless, colorless humanity, as barren of originality as it is of nationality, as uninteresting as it is unoriginal.

During a 1974 visit to Norway, his wife’s homeland, Kennan noticed a white woman with an Oriental child. He assumed the child’s presence was due “to the sentimentality of some Norwegian missionary.” He was charmed by the little girl, but saw what she portended:

How great is the prodigality of the Orient, which could produce and cast off no end of these exquisite, intelligent little creatures without even feeling the loss, the prodigality . . . which, in its pitiless vitality, will no doubt someday engulf and enslave whatever may, by that time, be left of us inane, pampered westerners.

Kennan clearly believed in inherited racial characteristics. He deplored “the great American delusion” that “the traditions and habits, the capacities for self-restraint, and self-discipline and tolerance that have developed historically, in close association with the Christian faith, in and around the shores of the North Sea” were “readily communicable to those who did not inherit them.”

At least in his diaries, Kennan was a frank eugenicist:

Nothing good can come out of modern civilization, in the broad sense. We have only a group of more or less inferior races, incapable of coping adequately with the environment which technical progress has created. . . . This situation is essentially a biological one. No amount of education and discipline can effectively improve conditions as long as we allow the unfit to breed copiously and to preserve their young. Yet there is no political faction in the world which has any thought of approaching the problem from the biological angle. Consequently there is really nothing positive to be expected from any political movement now in existence. There is nothing which any of them can do except to give the present generation of inferior beings a training and discipline which will in no way alter their offspring . . . . These political factions may profoundly influence environment; they will not alter heredity!

Already by the 1960s, Kennan had become a strong environmentalist, and worried about population pressure. In 1982, he wrote:

Our country is of course some 200 percent overpopulated but we have at least stabilized our own birthrate, and could perhaps face the future with confidence if we were the only ones concerned. It is the others–the Mediterraneans, the Muslims, the Latinos, the various non-WASPs of the Third and not-quite Third Worlds–who are destroying civilization with their proliferation, our civilization as well as theirs.

Immigration had another strategic consequence, namely, the creation of new domestic pressure groups for intervening abroad in places of no strategic importance. In 1988, Kennan listed the three factors that had distorted American diplomacy since WWII: “a Manichean view” of the world, “a militarized view of . . . external relationships,” and putting “foreign policies so extensively at the service and prejudices of ethnic minorities.” He believed that American postwar policy in the Middle East and Africa, in particular, had been largely formulated to appeal to, or at least not offend, black and Jewish voters.

As early as 1984, Kennan wrote in his diary that “immigration for permanent residence [should] be effectively terminated,” and border controls “greatly strengthened.” He called for an immigration moratorium in his 1993 volume of essays, Around the Cragged Hill. The book was a New York Times’ bestseller for three weeks, but was largely ignored by the establishment. Kennan complained in his diary that while Washington continued to honor him with awards, policy-makers never listened to him.

Kennan’s last public statement on the subject was during an interview with the New Yorker magazine in 2000: “I think the country is coming apart, partly because of its susceptibility to immigration.” It turned out that America’s greatest enemy in the 20th century was not fascism or communism, liberalism or socialism, but its own addled and corrupt rulers.

These diaries are an intimate glimpse into the mind of a deeply intelligent and thoughtful man. This review has concentrated on Kennan’s observations on racial and national questions, but his writing is full of insights into culture, history, and human nature. His prose is always masterful and clear. To read Kennan is to find oneself brooding on how vastly superior he was in every way to the sycophants and self promoters who rule us today. He was perhaps the last of a WASP aristocracy of the spirit that once guided our country.