The Great Replacement: Richmond

Gregory Hood, American Renaissance, July 31, 2020

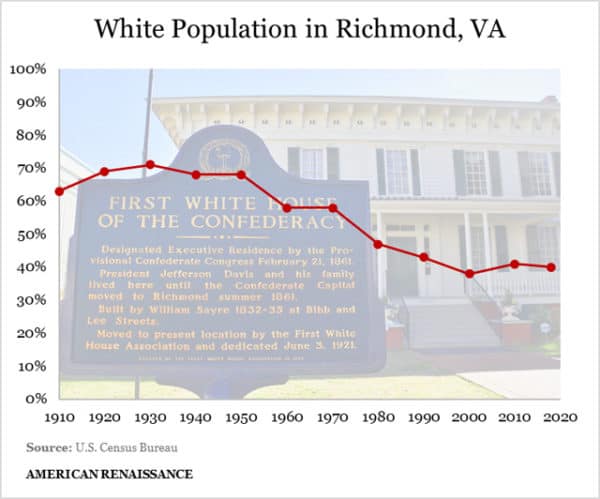

This is the fifth in a series about the continuing disappearance of whites from American cities (see our earlier entries for Birmingham, Washington, D.C., New York City, and Chicago). Many people still pretend that The Great Replacement is a myth or a conspiracy theory, but the graphs that accompany each article in this series prove them wrong. Every city has a different story but all have seen a dramatic replacement of whites by minorities.

Until very recently, most Northern cities enjoyed overwhelming white majorities. Southern cities haven’t been so lucky because most blacks stayed in the region until the Great Migration. However, Richmond was a white-majority city until desegregation. Today, blacks and deracinated whites in the city are destroying monuments to Southern resistance, finally consolidating their cultural as well as political conquest of the former Confederate capital.

Retreating Confederates and advancing Yankees destroyed much of Richmond during the Civil War, but residents rebuilt quickly. The Robert E. Lee statue on Monument Avenue was unveiled in 1890, and Stonewall Jackson’s in 1919. Douglas Southall Freeman, whose biographies of George Washington and Robert E. Lee and whose study of the Confederate high command in Lee’s Lieutenants made him perhaps the best known historian in America, took over the Richmond News Leader in 1915 and was editor for decades.

The Gen. Robert E. Lee Monument in Richmond, Virginia. (Credit Image: © Chuck Myers / MCT / ZUMAPRESS.com)

In 1922, Richmond was also the birthplace of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America, which successfully lobbied for Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924, banning interracial marriage. However, Richmond was also a Mecca for black political organizations, hosting the 30th anniversary convention of the NAACP. During World Wars I and II, the Civil War era Camp Lee was used to mobilize American soldiers. In 2015, the Army said it had kept the name in a spirit of “reconciliation, not division.”

Richmond was more than two-thirds white before the Supreme Court ordered school desegregation in 1954. Virginia responded with a “massive resistance” campaign, closing local schools rather than desegregate them. Virginia’s Harry Byrd promoted “massive resistance” because he thought the Commonwealth could rally the rest of the South: “If we can organize the Southern states for massive resistance to this order [of the Supreme Court], I think that in time the rest of the country will realize that racial integration is not going to be accepted in the South.” Conservative columnist James Kilpatrick developed the doctrine of “interposition” to justify white resistance, arguing that state sovereignty meant the Commonwealth could ignore the Supreme Court ruling. In his review of George Lewis’s Massive Resistance: The White Response to the Civil Rights Movement, Morris V. de Camp writes that efforts to stop desegregation ultimately failed, so “whites pretended to support the package of The Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr. . . . while they fled its effects.” This is especially true of Richmond’s public schools.

Robert Pratt writes in A Promise Unfilled: School Desegregation in Richmond, Virginia 1956-1986 that aggressive federal courts were able to reduce “massive resistance” to “shambles” by 1959. Richmond’s white parents changed tactics; they put their children in private schools. “Richmond’s schools, 57 percent white in 1954, were more than 86 percent black by 1986,” wrote Professor Pratt. He added that some “black pioneers” at white schools didn’t perform well because, as he claims, white teachers were sometimes “condescending,” and blacks had “lowered self-esteem.” This raises the question of why desegregation was a good idea.

There was white flight both from the schools and the city. Richmond went from 68 percent white in 1950 to a white minority by 1980. In 1970, still-white Richmond annexed part of mostly white Chesterfield county to stave off a black majority, but this backfired. First, whites in Chesterfield didn’t want to be lumped in with Richmond and its black population. Second, the federal courts ruled that Richmond’s “at-large” election system was now illegitimate because the annexation was for racial reasons. In City of Richmond v. United States (1975), the Supreme Court said Richmond had to adopt a “ward” voting system to give blacks political power.

Whites began moving out of the expanded city and blacks moved in. In 1977, Mayor Henry L. Marsh III became Richmond’s first black mayor, chosen by the city council after blacks won a majority on the council. White leaders worried that blacks would do something to Monument Avenue; they have now been vindicated.

Once Richmond became majority-black, many blacks wanted a mayor directly elected by voters, but they feared rich whites might out-organize them in an “at-large” system. Thus, Richmond developed a compromise that requires a mayor to win most of the votes in a majority of city council districts. “The compromise was meant to prevent the election of a Mayor who did not have explicit support by those in districts where Black voters resided,” explained an article from William & Mary Law School. Once again, the system deliberately protected black power at whites’ expense.

Whites continued to move away, and blacks began to exercise power. In 1996, the city council approved putting up a statue of black tennis player Arthur Ashe on Monument Avenue, an idea proposed by City Councilman Henry “Chuck” Richardson, who was reportedly inspired by scenes of people tearing down Communist monuments in Eastern Europe. Not long after, a jury convicted Mr. Richardson of distributing heroin, but the idea did not die.

Current Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney, a black man, said monuments that honor Confederate heroes “exemplify hate, division, and oppression.” However, he also said the reason they are being removed “is because of public safety first.” This is a tacit admission that the city can’t maintain order. The statues are coming down, but rioters haven’t stopped. There was brisk action last weekend with fires, graffiti, and broken windows. Some police reportedly blamed “white supremacists” for the riots, but one well-known antifa propagandist is among the arrested. The weekend before, there were five shootings, including a three-year-old and a seven-year-old in seven hours. Just a few days ago, five people were shot and one killed outside a McDonald’s. “Why are we so mad at the white folks when we don’t even care about ourselves?” asked the victim’s mother.

My view is that blacks have chosen racial triumph over whites rather than protecting themselves. As they shoot each other and destroy their neighborhoods, they have turned the former Confederate capital into just another majority-black city. They may not be able to build, but they can destroy what whites built, and that seems to be enough for them.

The ghostly hologram of George Floyd projected over the statue of Robert E. Lee shows that the Lost Cause is truly lost, and that the Christian South has been conquered. However, it also vindicates those who fought and died for the Confederacy. Robert E. Lee’s statue still stands, but not for long. If his spirit could still see Richmond today, I can only imagine he would regret surrendering, no matter how hopeless things looked in 1865.

Amazing hologram of George Floyd in Richmond. You can hear the Floyd Family speaking in the background. #richmond #GeorgeFloyd pic.twitter.com/0uFK7ePsAc

— pace (@ReggiePace) July 28, 2020