The Plan of San Diego

Sinclair Jenkins, American Renaissance, October 31, 2019

San Diego, Texas, is a tiny, nondescript town in the deep south of Texas. As of the US census of 2010, fewer than 5,000 people lived there. Unsurprisingly, most of them speak Spanish and have deep roots in Mexico. The Texas borderlands have been this way since the Texas Revolution, and thanks to mass immigration from Mexico and Central America, Texas and the rest of the Southwest move closer towards the Hispanic orbit every day.

Despite the hopes and dreams of Catholics, a more Hispanicized America means more Santa Muerte cultists, more Santeria practitioners, and more drug-addled gangsters with avowed appreciation for Satan. Even church-going Hispanics are more likely to believe in Liberation theology, which combines socialism with anti-white vitriol.

Back in 1915, the United States got a glimpse of its future. On January 6, 1915, a manifesto was drawn up in San Diego (then having a population of 2,500 people, 75-percent of whom were Hispanic [1]). Later dubbed the Plan of San Diego, the Spanish-language document called for a race war against Anglo Texans:

On the 20th day of February, 1915, at two o’clock in the morning, we will arise in arms against the Government and Country of the United States of North America, ONE AS ALL AND AS ONE, proclaiming the liberty of individuals of the black race and its independence of Yankee tyranny which has held us in iniquitous slavery since remote times… [2].

Despite the invocation of “the black race,” the purpose of the Plan of San Diego was to turn southern Texas into an independent republic controlled by Hispanics. Under the banner of “Equality and Independence” and led by the so-called “Liberating Army For Races and Peoples,” the rebels, who took the name of Seditionistas, hoped that by shedding enough Yankee blood, the Hispanic republic would gain independence and rejoin Mexico. Thus, the stain of the American victory of 1846-1848 would be wiped clean and “North American imperialism,” which had taken Mexican territory “in a most perfidious manner” would be defeated [3].

The plan also called for an independent republic in the Southwest for blacks. The Apaches would also get Anglo land, while the Japanese were to join in the Hispanic and black war against Anglo whites. In general, the Plan of San Diego, which was signed by Mexican nationals and US citizens of Mexican ethnicity, called for an ethnic cleansing of English-speaking whites in Texas and the Southwest, and wanted Hispanic, black, Indian, and Japanese (but not Chinese) to do the killing. The plan prompted years of anti-white violence and codified a brand of Hispanic chauvinism that continues to this day.

Tensions between Anglos and Tejanos (Hispanics living in Texas) were long simmering by the winter of 1915. According to Benjamin Heber Johnson in Revolution in Texas, “The United States’ conquest of the Mexican north was a traumatic event for the conquered, often bringing dramatic, wrenching changes” [4]. The main change was demographic: an unending influx of whites. The one exception was New Mexico, which managed to cling to its Spanish Creole character well into the 20th century. (These days, even though New Mexico was once home to conquistadors and their offspring, a majority of phenotypically white New Mexicans identify as Hispanic rather than white.)

In Texas, the Anglo takeover began in the 1830s. At the Alamo, English-speaking Texans (called “Texians”) were joined in their fight for Texas independence by U.S. citizens from the South and frontier states such as Kentucky and Tennessee, and by immigrants from Denmark and Great Britain [6]. Tejanos also fought at the Alamo and for Texas independence, but the revolution turned into a race war once General Antonio Lopez of Santa Ana — Mexico’s version of Napoleon Bonaparte — made it his mission to “rid Texas of its Anglo-Celtic colonists” [7].

“The Fall of the Alamo” (ca. 1903) by Robert Jenkins Onderdonk.

After the Texian victory and the incorporation of the Republic of Texas into the United States, the formerly Mexican province assimilated into the culture of the American South. Texas later gave the Confederate Army some of its best fighting men, including the Texas 4th Infantry, which fought under John Bell Hood. South Texas, however, especially the border region of the Nueces Strip (between the Rio Grande and the Nueces River), retained its Mexican character. In this region, which included the tiny village of San Diego, Tejano cattle barons used an Old World-style patronage system that included Anglo machine politicians who relied on Hispanic votes. Often well-to-do Anglo and Tejano families intermarried, and many Anglo settlers converted to Roman Catholicism. [8]

Things began to change after the railroads opened south Texas to more immigrants. Within a few years, the Nueces Strip was home to thousands of English-speaking farmers, laborers, and boomtown types. These new arrivals “were generally blind to differences among the ethnic Mexican population,” and many saw Spanish-speakers as nothing more than a source of cheap labor [9]. Such economic and cultural displacement led to bad blood, but economics alone cannot explain the antipathy towards Anglos found in the Plan of San Diego. The seventh point in the manifesto demanded that “Every North American over sixteen years of age shall be put to death” [10]. What was driving the signers of the Plan of San Diego towards ethnic cleansing?

One cannot understand the Plan of San Diego without recognizing that it was part of the wider Mexican Revolution. The spark of the revolution was a different plan, written in 1910. The liberal Francisco Madero had been a candidate in the 1910 elections against General Porfirio Diaz, the conservative strongman who had controlled Mexico since 1884, but Diaz arrested Madero and held him during the election. Madero then escaped and wrote the Plan of San Luis Potosi, which called for annulment of the election and a military uprising against Madero. Men such as Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa answered the call, ambushing and terrorizing the federal army, while Emiliano Zapata took aim at the rural politicians, or caciques, in the south. Within a year, Ciudad Juarez was in rebel hands and Madero was declared Mexico’s new president.

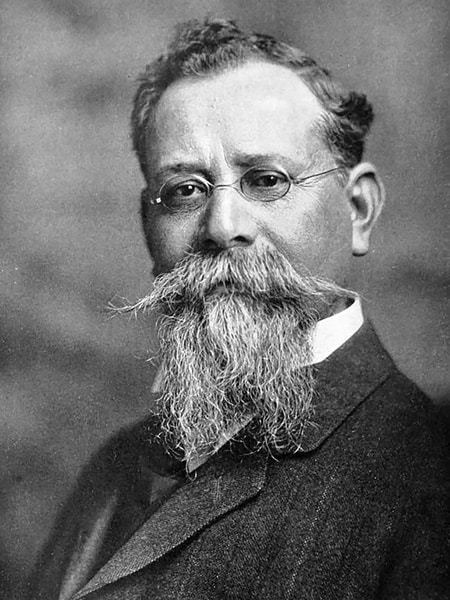

The revolution then turned against itself. Zapata broke from Madero because he would not grant land to Indians, and Orozco and Villa turned against Madero for not reforming Mexico fast enough. The revolution of 1910 fractured into multiple civil wars, with army officers and bandit leaders carving up fiefdoms throughout the country. In February 1913, army general and warlord of Mexico City, Victoriano Huerta, was installed as president following a backroom deal that included Madero and US Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson. Huerta had Madero executed, which kept the revolution going. Yet another plan, the Plan of Guadalupe called for Huerta’s ouster, but his replacement with Venustiano Carranza only led to more chaos.

Throughout this period of anarchy, Mexican fighters and refugees crossed the American border with ease. South Texas became a den of spies, with pro-Villa and pro-Carranza forces freely carrying out assassinations. The plan of San Diego was signed by both Huerta and Carranza supporters [11]. Historians Charles H. Harris III and Louis R. Sadler have uncovered proof that the plan was an “instrument of Mexican government policy” written by Carranza’s government [12].

Pancho Villa

The Plan of San Diego was linked to the effort by the Germans to build an alliance with Mexico in the event that the United States entered the First World War against Germany. In return for attacking the United States, Germany would help Mexico take back Texas, Arizona and New Mexico, which it had lost in the Mexican-American War. This proposal, outlined in the notorious 1917 Zimmermann Telegram, included the race war that was part of the Plan of San Diego.

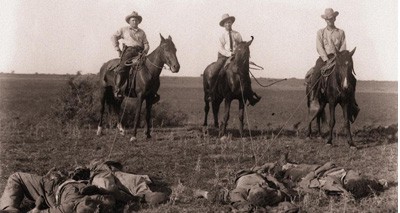

The plan, written two years earlier, lit the anti-white powder keg of Mexican animosity, even without German support. Beginning in the summer of 1915, Mexican rebels and bandits began crossing into the lower Rio Grande valley, where they carried out thefts, kidnappings, and murders [15]. Sedicionistas “launched some 30 raids against ranches, railroads, telegraph lines and other targets in the border region, killing nearly two dozen US citizens” [16]. In one incident, raiders kidnapped, tortured and decapitated a US soldier before displaying his head on a pole overlooking the border [17]. In January 1916, Villa and his men captured a train near Chihuahua City. Onboard were 18 American miners returning to Mexico to work in American-owned mines. Villa and his men ordered the Mexican passengers off the train and then then murdered 17 of the Americans [18].

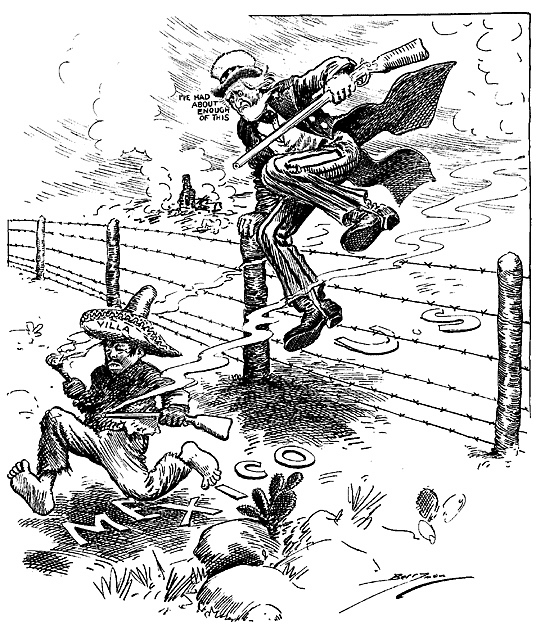

President Woodrow Wilson then sent half of the US Army to the US-Mexican border in November 1915 [19], but raids continued. On March 9, 1916, Pancho Villa and approximately 500 mounted men stormed into Columbus, New Mexico with shouts of “Muerte a los gringos!” For two to three hours they set fire to buildings, attacked civilians and members of the 13th US Cavalry at Camp Furlong. Although caught off guard by the raid, the Americans fought back bravely. When Villa’s men entered the camp kitchen, cooks attacked them with shotguns, boiling water, and axes. Across town, a barefoot lieutenant roused his men and their French-made Benet-Mercie machine guns and shot at every sombrero they could see [21]. The death toll was 10 American civilians, eight American soldiers, and about 80 of Villa’s men.

The Columbus raid angered Americans. President Wilson sent 140,000 National Guard soldiers to secure the border, and General John “Blackjack” Pershing led what was called the Punitive Expedition across the border, deep into northern Mexico. Pershing, with the help of Carranza’s army, managed to kill 400 of Villa’s men in three months [22]. The Army failed to capture Villa, but it cleared northern Mexico of his followers.

“I’ve Had About Enough of This” (1916) by Clifford K. Berryman.

The border was still volatile. On the first day of 1918, in Nogales, Arizona, an American soldier shot a Mexican who was illegally crossing into the United States. There followed a series of tit-for-tat shootings, until Mexican soldiers and armed civilians attacked the border on August 27. It appears to have been a planned assault supported by machine gun nests and snipers in the Sonoran hills [23]. Later dubbed the Battle of Ambos Nogales, five US soldiers and one American civilian were killed; 30 Mexican soldiers died, though casualty counts vary according to different sources. The battle ended at 7:45 p.m., when American soldiers and civilian auxiliaries saw a white flag fluttering in the Sonoran hills. Both sides agreed to build a border fence to help control the situation.

Much of this bloodshed was the direct result of the Plan of San Diego and the machinations of the Mexican government. It was Carranza’s government, specifically Emiliano Nafarrate, the army officer in charge of keeping the peace on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande between Brownsville and Laredo, Texas, who “permitted Plan [of San Diego] activities within his area and actively sponsored them” [24]. This mixture of revolutionary activity and racial grievance prompted a brutal response from Anglo Texans and the Texas Rangers. “Extralegal executions became so common,” Johnson notes, “that a San Antonio reporter observed that the ‘finding of dead bodies of Mexicans . . . has reached a point where it creates little to no interest’” [25]. This Anglo violence forced many Tejano’s to drop their Mexican identity in favor of a Mexican-American one.

Mexican president Venustiano Carranza ca. 1915.

An uneasy truce held until the 1960s. Mexican radicals then began eschewing all things American in favor of Mexican nationalism and “brown pride.” The theory of Aztlan, which is central to movements such as La Raza, seeks to resurrect the mythical Aztec homeland by returning the American Southwest to Mexico. The Plan of San Diego is one of the founding documents of Aztlan thinking, as Mexican radicals living in the US see mass immigration and demographic displacement as a version of the warfare called for by the 1915 manifesto. One of the first casualties of this racial Reconquista could be Texas, which, according to most data, is poised to vote Democrat by as early as 2020.

This is the thinking behind the Plan of Santa Barbara, drafted in 1969, as the founding document of MEChA or the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (Chicano Student Movement of Aztlan), which works for the liberation of “la Raza” or the Hispanic race. The irredentist fight continues. Lately — and comically — the movement has voted to change its name and remove the words Chicano and Aztlán because of worries that they are homophobic, anti-indigenous, and anti-black. The idea of restoring Aztlán has always been explicitly anti-white, but that is obviously nothing to apologize for.

Mexico has never been a genuinely friendly country. If the United States is to assert its sovereignty there must be deportations and repatriations. Our government must investigate Mexican meddling in American politics. Despite what we hear about Russia and Ukraine, Mexico, Qatar, Israel, and China are the biggest corruptors of American politics.

Mexico and the United States were both founded by European Christians as lands for themselves and their progeny. Liberalism, false egalitarianism, and racial grievance mongering have obscured this fact. To stop the Plan of San Diego from becoming anything more than a piece of history, nationalists and patriots in both countries must resurrect and defend their European inheritance — one born from the swords of Castilian conquistadors and the other from the blood and toil of frontiersmen drawn from the British Isles and the cold forests of Northern Europe.

* * *

References:

[1]: Charles H. Harris III and Louis R. Sadler, The Plan of San Diego: Tejano Rebellion, Mexican Intrigue (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2013): 1.

[2]: Harris and Sadler, The Plan of San Diego, 2.

[3]: Ibid.

[4]: Benjamin Heber Johnson, Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and Its Bloody Suppression Turned Mexicans into Americans (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003): 10.

[5]: Ibid.

[6]: Stephen L. Hardin, Texian Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revolution, 1835-1836 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996): 152.

[7]: Ibid.

[8]: Johnson, Revolution in Texas, 15.

[9]: Johnson, Revolution in Texas, 39.

[10]: Harris and Sadler, The Plan of San Diego, 3.

[11]: Rolando Hinojosa Smith, “River of Blood,” Texas Monthly, 1 Jan. 1986.

[12]: Harris and Sadler, The Plan of San Diego, x, 13.

[15]: James A. Sandos, “Pancho Villa and American Security: Woodrow Wilson’s Mexican Diplomacy Reconsidered,” Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Nov. 1981): 295.

[16]: P.G. Smith, “Divided Against Itself,” Military History, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Nov. 2019): 35-36.

[17]: Ibid.

[18]: Ibid.

[19]: Sandos, “Pancho Villa and American Security,” 295.

[20]: Sandos, “Pancho Villa and American Security,” 296.

[21]: Thomas Boghardt, “Chasing Ghosts in Mexico: The Columbus Raid of 1916 and the Politicization of U.S. Intelligence during World War I,” Army History, No. 89 (Fall 2013): 7.

[22]: Sandos, “Pancho Villa and American Security,” 303.

[23]: Smith, “Divided Against Itself,” 37.

[24]: Sandos, “Pancho Villa and American Security,” 297.

[25]: Johnson, Revolution in Texas, 3.

[26]: J.H. Elliott, Imperial Spain, 1469-1716 (London: Penguin, 2002): 63.