The Legacy of Pim Fortuyn

Eric Rembrandt, American Renaissance, September 19, 2014

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

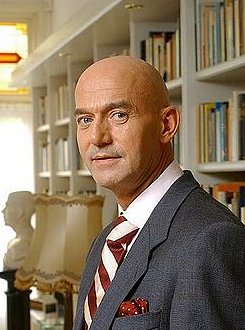

Pim Fortuyn (Credit Image: Roy Beusker / Wikimedia)

It is five minutes to midnight, not just in the Netherlands but in Europe. I stand with this country, which has been built up in six centuries. There is a goddamned fifth column in this country that wants to take us into the abyss. I tell them [foreigners], you can stay here, but you adapt. When I visit their neighborhoods they tell me Allah is great, that I am a dirty pig and the leader of the Christian Democrats is a Christian dog. The people are fed up with the soft approach of the ruling parties, which is the reason I have won many seats during the elections. Fine, then I will be murdered. But the problem will remain. — Pim Foruyn

It has now been 12 years since the assassination of Pim Fortuyn, the flamboyant Dutch politician who was one of the first to break the taboo and call attention to the deadly threat of Muslim immigration. He was one of very few critics of mass immigration who was able to reach a broad audience, and the success of his movement broke down barriers that have never been fully rebuilt.

Fortuyn was born in 1948. In 1981 he received a doctorate in sociology at the University of Groningen, and for a time taught Marxist sociology at the same university. In 1990, Fortuyn moved to Rotterdam, where he taught at Erasmus University. Although he was, himself, a leftist, he began to notice that the political landscape and media were completely dominated by what he called “the left-wing church.” He also saw first-hand the failures of multiculturalism in Rotterdam, which received large numbers of immigrants during the 1960s and 1970s, most of them Muslim.

In 1997, he wrote a book, Against the Islamization of our Culture, which shocked the country and established him as a prominent critic of immigration policy. He began to appear on Dutch television and in the newspaper, where he relentlessly criticizing the government and Islam. He was soon notorious for saying he wanted a “cold war” with Islam, which he called “an extraordinary threat” and “a hostile religion.”

When he was invited on talk shows, he was often treated like a lunatic, and was usually outnumbered by hostile opponents. However, Fortuyn, who was openly homosexual, had a suave debating style that often routed his opponents.

In one television debate, he flaunted his homosexuality at a Muslim cleric. When the imam responded with furious anti-homosexual invective, Fortuyn calmly explained to viewers that this is the kind of Trojan horse for intolerance the Dutch were letting into their country in the name of multiculturalism.

In 2001, the increasingly visible Fortuyn was put at the head of the new Livable Netherlands party’s list of candidates, and was largely responsible for the party’s success in the Rotterdam city elections. In February 2002, he gave an interview to a Dutch newspaper, Volkskrant, in which he said that Islam was “a backward culture,” and that if it were legally possible he would close Holland’s borders to Muslims. He said Muslims had no understanding democracy or of the rights of women, homosexuals, or minorities, and that in sufficient numbers they would try to impose Sharia law on Holland. He added that it might be necessary to repeal anti-racism laws in order to protect freedom of speech.

This was too much for Livable Netherlands, and he was forced out of the party the day after the interview appeared. By then Fortuyn had bigger plans, and had his eye on the Dutch national elections. His criticism of traditional parties, immigration, multiculturalism, and Islam had attracted a large new group of voters, and with the help of several property magnates, he founded the Lijst Pim Fortuyn (LPF).

The LPF quickly started polling at rates better than any other party. It attracted voters from the entire political spectrum, but especially from the Left. The same year, 2002, Fortuyn published another influential book, The Wreckage of Eight Purple Years. This was a powerful and well-received critique of the “purple” (conservative, liberal, and social democrat) governments that had been in power for almost a decade. If there had been an election when Fortuyn was at the peak of his popularity, he might well have become prime minister.

The establishment realized Fortuyn was a threat, and began a program of demonization. He had been called “right wing” and “racist,” but he always rejected these labels. He insisted–sincerely, it appears–that he did not object to Muslims because of their race but because they were incapable of appreciating modernity, which Fortuyn defined in terms of the achievements of the Left. For this reason, he rejected any comparison to Jean-Marie Le Pen in France or Jörg Haider in Austria, figures he considered genuinely “right wing.” After the establishment of the LPF and its meteoric rise in popularity, the media and politicians–Dutch and foreign alike–went further, and started calling him the new Hitler or Mussolini.

Fortuyn started getting death threats, and at the time of the publication of his 2002 book, he was hit with a pie filled with feces and urine. He requested security guards, but the Dutch authorities refused to protect him. In 2005, it was revealed that instead of protecting him, the Dutch secret services were spying on him. They tapped his phone and even followed him into gay clubs. Leaked documents also showed they were investigating other members of the LPF.

The LPF continued to build a platform, with immigration control as its central plank. Fortuyn also argued that asylum seekers and war refugees should find shelter in their own part of their world rather than in the West. Although it is not well known outside of Holland, the LPF had a comprehensive platform that made many enemies, including:

- The Political Elite. Fortuyn blamed the “purple” government or “the left-wing church” for the failing multicultural state, a weak police force, and a mediocre health care system.

- Muslims. All Muslim organizations hate him.

- The Dutch royal family. Fortuyn criticized Queen Beatrice for interfering too much in government matters, and complained that Crown Prince William Alexander was old fashioned and too strongly influenced by the military.

- The uniformed services. He thought the police were ineffective, and he wanted to cut military spending and radically reorganize the armed forces. He opposed Dutch participation in development of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, which he thought was a huge waste of money.

- The European Union. The EU was not as powerful as it is today, but Fortuyn already recognized its love of wielding power that was accountable to no one. As he said, “The elite of the European Union does not like democracy, in fact this meritocratic-bureaucrat clique is not being controlled by anyone, and they intend to keep it that way.”

Of course, Fortuyn had many friends who shared his beliefs. One was Theo van Gogh, a film-maker and columnist, and great-grand nephew of the painter. Van Gogh frequently criticized Dutch multicultural society, and was best known for his short film Submission, about the abuse of women in Islamic society. Van Gogh and Fortuyn sometimes appeared on television together; no one knew that both would soon be dead.

The early part of 2002 was a chaotic time for Fortuyn. His party had been founded only in February, but had to prepare for general elections in May. As the LPF polling numbers climbed, the demonization campaign went into high gear, and Dutch Public Television was especially strident in denouncing the party. Just two months before he was assassinated, Fortuyn denounced the hysteria that had been built up against him:

If something happens to me, the purple politicians are also responsible. They cannot just tell you they have not wanted an attack. No. They have created the climate, and this has to stop.

On May 6, 2002–just 11 days before the election–Fortuyn gave a radio interview in the city of Hilversum, in which he discussed polls that suggested he might be forming the next government. When he left the studio, a man approached him in the parking lot and shot him in the head, chest and neck. Fortuyn died soon after. The murderer, Volkert van der Graaf, explained at trial that the rise of Fortuyn was like the rise of Nazism in the 1930s. He said he had murdered Fortuyn to stop him from exploiting Muslims as “scapegoats,” and for targeting “the weak members of society.” Van der Graaf was sentenced to 18 years in prison, but received a conditional release in May of this year, after serving two-third of his sentence.

The Netherlands was shocked by the assassination, which was the first political murder in its democratic history. Riots broke out in The Hague, near the national parliament, but the elections went ahead as planned. The LPF polled as the second largest party, with 17 percent of the vote. Many potential LPF voters had switched to the Christian Democrats (who never participated in the demonization of Fortuyn), because they felt that the party had no value without its leader–and they were proven right. It took just two years of infighting, financial mismanagement, and lackluster leaders to drive the party to just 1 percent support, and it disintegrated soon thereafter.

In November 2004, Fortuyn’s ally Theo van Gogh was butchered on the streets of Amsterdam. Mohammed Bouyeri, a Dutch-Moroccan Muslim, shot him eight times and slit his throat. Mr. Bouyeri then drove a dagger into van Gogh’s chest with a note that threatened one of his film collaborators with death. Mr. Bouyeri was sentenced to life in prison.

The Dutch politician who now most closely resembles Fortuyn is Geert Wilders, whose Party for Freedom is now the fourth-largest party in parliament. He has famously said that the Koran “incites hatred and killing and therefore has no place in our legal order.” He believes there should be no more Muslim immigration, and that all Muslims in Holland should be paid to go home. If Muslim immigration continues, he says, “We are heading for the end of European and Dutch civilization.”

Although Fortuyn is dead and his party disintegrated, many of his former supporters now vote for Mr. Wilders. Fortuyn was the first Dutchman to give voters a real alternative to the traditional parties and to give voice to that large part of the population that realizes immigration threatens our culture. Fortuyn broke the taboo on frank talk about immigration, an achievement he paid for with his life.

Pim Fortuyn also shows the role just one man can play in history. He started a movement single-handedly. The almost immediate self-destruction of that movement after his assassination shows how essential he was. This always seems to be the case with movements that depart from convention. Traditional parties of the center-right or center-left can plod along with virtually anyone in charge, but a party with a fresh perspective needs extraordinary and charismatic leaders.

Racially aware critics complain that Fortuyn never opposed immigration on the basis of race. Conservatives complain that he opposed immigration for the wrong reasons, namely, that Third-Worlders do not adapt to the features of Western societies that conservatives most dislike: feminism, homosexual marriage, and other forms of egalitarianism.

These critics do not realize that in the late 1990s and even today, it is impossible to win broad support in Holland by criticizing immigration from the Right, and certainly not from a racial perspective. Such views can be too easily caricatured as Nazi or white supremacist, and are confined to the fringe. Pim Fortuyn, with his PhD, his expensive suits, his urbane manner, and his open homosexuality, could attack the horrible consequences of immigration without terrifying Dutch voters. The enormous response he received shows just how much the Dutch resent the transformation of their country, and how willing they are to act on that resentment if they can do so in a way that does not seriously threaten their respectability.

The success of Nigel Farage in Britain and the rise of Marine Le Pen in France–after she purged the National Front of “extremists”–are further proof of the deep yearning Europeans have for leaders who promise to protect and restore their nations. Someday, open racial appeals will take their legitimate place in the formation of public policy, but that day has not yet come.

This video and this one are rare examples of Fortuyn debates that have been given English subtitles.