You Can’t Say That Here!

F. Roger Devlin, American Renaissance, January 17, 2014

Subscribe to future audio versions of AmRen articles here.

Greg Lukianoff, Unlearning Liberty: Campus Censorship and the End of American Debate, Encounter Books, 2013, 294 pp., $25.99.

In 1998, Prof. Alan Charles Kors and lawyer Harvey A. Silvergate published an exposé of violations of free speech on college campuses. The Shadow University was a best seller, and readers responded with so many horror stories and pleas for help that the authors established the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) in order to protect free speech.

In 2001, Greg Lukianoff was appointed the organization’s director of legal and public advocacy, and he became the president in 2006. Unlearning Liberty is his account of 11 years with FIRE, during which he reviewed thousands of cases of campus censorship and represented hundreds of students and faculty.

A uniquely Western achievement

Mr. Lukianoff points out that what he calls the “system of free speech, public disclosure, and active debate” is not universal, but a historical achievement specific to Western civilization. It is the fruit of many centuries, and is still vulnerable. Free speech rests on two principles:

First, no one gets the final say; we all must accept that no argument is ever really over, as it can always be challenged if not disproved down the line. Second, no one gets special, unchallengeable claims of “personal authority.” No one individual is immune to the criticism of others and none can claim to be above intellectual reproach. No one is omniscient or infallible, so we are all forced to defend our arguments with logic, evidence, and persuasion.

Mr. Lukianoff reports that today’s students often do not understand the importance of this system. They are more likely to think that people should be muzzled if that is what it takes for groups from different backgrounds to get along. One 2004 survey of high school students reported that they were “far more likely than adults to think that citizens should not be allowed to express unpopular opinions, and that the government should have a role in approving newspaper stories.”

University speech codes have been struck down nearly every time they have been challenged in court — more than two dozen times since 1989 — and this has created a false impression that the issue has been resolved. However, new speech codes spring up faster than old ones are struck down — often on the same campuses.

FIRE reports that 62 percent of American institutions of higher learning have at least one policy that “clearly and substantially” restricts freedom of speech. In most other schools the situation is ambiguous. Only 3.7 percent clearly protect freedom of speech. Many speech codes contain vague prohibitions against “incivility,” “disrespect,” or “offending” or “embarrassing” anyone.

Colleges often use a very loose interpretation of the legal concept of “harassment” as a way to control speech. As Mr. Lukianoff points out, the Supreme Court has limited “harassment” to only to cases in which:

unwelcome discriminatory behavior, directed at a person because of his or her race or gender, is ‘so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive, and so undermines and detracts from the victims’ educational experience, that the victim-students are effectively denied equal access to an institution’s resources and opportunities.’

Universities, however, consider trivial things to be “harassment:” “stereotypic generalizations,” “words that interfere with another person’s comfort,” “expressions deemed inappropriate,” “jokes that demean a victim’s culture or history,” “inappropriate gender-based activities, comments or gestures,” and “use of generic masculine terms to refer to people of both sexes.”

This last category means that to say, “Every student should park his car in lot B” could be harassment. If policies like this were enforced, nearly all students would be guilty every day. Of course, the policies are not enforced consistently, and as Mr. Lukianoff points out, the students most likely to be charged are those who criticize or joke about the administration: “As any First Amendment lawyer knows, the first thing to go is any speech that criticizes or annoys those who decide which speech is free.” When a member of the student government at Michigan State University sent out e-mail criticizing decisions by the administration, the school punished her, declaring that “the University’s e-mail services are not intended as a forum for the expression of personal opinions.” Of course it was for expressing personal opinions; just ones that did not criticize the university.

St. Augustine’s College in Raleigh, NC, was hit by a tornado in April, 2011. Two days later it announced that classes would resume the next day. Many students complained since they were still without power. When the administration announced a public meeting to discuss the matter, a senior posted a comment on the college’s Facebook page urging students to come with “supporting documents to back up your arguments.” He was handed a letter barring him from his graduation ceremony because all students “are responsible for protecting the reputation of the college.”

Many cases of censorship are ideological. The Tufts University campus newspaper published an ad paid for by a student who thought the school’s “Islamic Awareness Week” painted too rosy a picture of Islam. The ad quoted verses from the Koran such as: “Therefore strike off their [unbelievers’] heads and strike off every fingertip of them.” It mentioned the punishment by death of homosexuals in some Muslim countries, and quoted an Islamic theologian’s opinion that “marriage is a form of slavery; the woman is the man’s slave and her duty therefore is absolute obedience.” Another student filed a harassment complaint, and Tufts “made free speech history by being the first institution in the United States to find someone guilty of harassment for stating verifiable facts directed at no one in particular.”

Administrations invent rules so they can go after student groups they don’t like. One Florida community college stopped a Christian group from screening The Passion of the Christ on the grounds that the film was “controversial” and “R-rated.” It soon came to light that the college had sponsored an R-rated movie just the previous year, and was hosting a production of Fucking for Jesus, described as “a piece about masturbating to an image of the Christian messiah.”

Students and faculty can be punished merely for referring to guns or violence, on the grounds that such talk is a “threat.” One student who gave a class presentation on the benefits of concealed-carry laws was reported to the police by his professor.

One popular technique for squelching speech is to designate an area on campus as the “free speech zone.” Such zones are often obscure corners of the campus. At Texas Tech, which has 28,000 students, the “free speech zone” is a tiny gazebo. A waggish mathematician computed that if all students wanted to use the gazebo at the same time, they would have to be crushed down to the density of Uranium 238.

Many universities inculcate students with propaganda about race and sex during orientation. In some cases, freshmen march through something called the “Tunnel of Oppression.” They walk through the rooms of a house where they watch live dramatizations of such themes as: “religious parents hate their gay children,” “Muslims will find no friends on a predominantly white campus,” and “white people believe all black women are ‘welfare mommas.’ ” One witness said freshmen come out with “hopelessness and shame” on their faces — no doubt exactly what the Tunnel of Oppression is designed to achieve.

The best known student “orientation” of this type was the University of Delaware’s mandatory Residence Life Program. It was called “treatment,” and included the following goal:

Each student will recognize that systematic oppression exists in our society . . . will recognize the benefits of dismantling systems of oppression . . . [and] will learn the skills necessary to become a change agent for social justice.

Freshmen were also asked highly personal questions, such as whether they could be friends with a homosexual, a black or a Middle Easterner, or whom they would be willing to date. The indoctrination was carried out by upperclassmen called Resident Assistants (RAs), who were put through intensive screening and training during the summer. Mr. Lukianoff writes that any qualms about the program were “met with hostility, intimidation and outright threats.”

RAs also got “confrontation training” in case they got resistance from freshmen, but they seldom had to use it. Investigators found only one clear case of a student who had resisted the “treatment.” When asked about her experience of oppression, she joked that people threw rocks at her because of her taste in opera. When her RA asked her, “When did you discover your sexual identity?” she replied, “That is none of your damned business.” The RA filed an “incident report” against her.

Mr. Lukianoff reports that RAs got other unusual training:

If an RA heard students discussing politics or religion (and some other topics), the RA would intervene and take control. The RA would give each student the chance to state his or her opinion and then tell the students to disperse. There was to be no questioning, no back and forth, no exchange, no probing, no explanations. RAs said they had been trained to quash such discussions as being uncivil.

When FIRE publicly criticized Delaware’s Residence Life Program in the fall of 2007, the university president suspended it, but Katherine Kerr and Jim Tweedy, who designed it, still work for the university. Dr. Kerr, who is still Executive Director of Residence Life & Housing, has tried to start it up again many times.

The American College Personnel Association (ACPA) gave the Residence Life Program an award, and has continued to hold it up as a model since it was suspended. Dr. Kerr later became president of the ACPA.

A few months after the program was suspended, the ACPA held a confidential meeting that was reported by a sensible infiltrator. A former program administrator lit a large candle “to represent the knowledge and responsibility that we have as student affairs and residence life professionals.” Next to it she placed several smaller candles to represent the students to whom “we pass on that light.” Mr. Lukianoff reports what happened next:

Suddenly, she blew out the large candle. She dramatically looked at the audience and said that in the fall 2007, ‘Our light went out,’ and it was ‘hate, fear, ignorance and stupidity’ that caused it to go out. ‘With this conference, we relight the candle . . . and hate, fear, ignorance and stupidity will not snuff it out [again].’ She relit the candle and continued in this vein, concluding, ‘Journey with me towards our revolution of the future.’

Students accused of violating vague behavior codes are often denied due process. College judicial procedures have been around for a long time, but were mainly about cheating on exams or plagiarizing papers. They have grown steadily in power and scope, and can now punish students for things many people consider normal. And on many campuses, open procedures and clear rules are considered an obstacle to the pursuit of justice.

Mr. Lukianoff writes about a presentation describing Michigan State University’s Student Accountability in Community (SAC) program at a national conference in 2002:

Before the session started, the presenters placed a graph on the whiteboard. At the bottom was listed ‘practical jokes’ and at the top was ‘assault’ and ‘rape.’ I thought to myself, ‘Please tell me they aren’t going to say that people who commit rape often start with practical jokes, so we should sentence practical jokers to “accountability training” as early as possible.’ Lo and behold, that was pretty much what they said.

Examples of offences for which a student might be sentenced included “a girl slamming a door after a fight with her boyfriend” or “a student being rude to a dormitory receptionist.” As punishment, students paid $50 for four discipline sessions. They also filled out a questionnaire about their offense — often several times, until they got the “correct” answers.

Students were handed a list of varieties of “violence,” and had to decide which they were guilty of. These included “putting someone down,” “using white privilege,” “any action that is perceived as having [not ‘that has’] racial meaning,” and even “using others to relay messages.” The student then had to acknowledge “full responsibility.”

The federal government makes things worse. In April 2011, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights decreed that all colleges that receive federal money — virtually all of them — must now rule on accusations of “harassment” according to the “preponderance of the evidence” standard. This is the lowest judicial standard, equivalent to “50 percent probability of guilt plus a feather.” The reason for this change was that student judicial procedures covering harassment could include the serious crime of sexual assault. However, the usual principle in law is that standards of evidence must be higher the more serious the offence: “clear and convincing evidence” (75-80 percent confidence) or “beyond a reasonable doubt” (99 percent confidence). The Obama administration is telling schools: “since sexual assault is such a serious crime, you must be more reckless about whom you find guilty.” And as Mr. Lukianoff points out, students can be found guilty of “harassment” because of trivial acts.

The same new DOE regulations require schools that allow appeals of convictions also to allow accusers to appeal a “not guilty” verdict. This, of course, is double jeopardy, prohibited under the Fifth Amendment.

Campus discipline can run parallel with court proceedings — and reach different results. In 2005, Charles Plinton, a graduate student at the University of Akron, was accused by another student of dealing drugs. The case against him was weak, and a criminal jury took only 40 minutes to find him innocent.

A campus judiciary proceeding, after the jury trial, using the “preponderance of evidence” standard, voted to suspend him. He could not afford a lawyer to fight the charges, and killed himself later that year.

“Discrimination” has been redefined to stop students from forming groups around shared beliefs. The original targets were Evangelical Christian groups, which were forced to accept non-Christian members, but this means any group is vulnerable to subversion by opponents who join because they want to harm or destroy it. Yet in June 2010, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that universities may enforce this novel concept of “discrimination” against any student group.

More administrators

One of the consequences of intrusions into free speech has been the dramatic expansion of the administrative class:

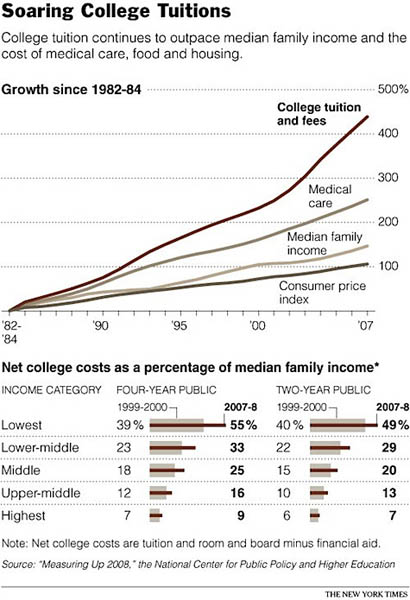

Between 1975 and 2005, the number of colleges, professors, students, and BA degrees granted all increased in the neighborhood of 50 percent. [But] during the same time period the number of administrators increased by 85 percent, and the number of administrative staffers employed by America’s schools increased by a whopping 240 percent.

In 2005, an important milestone was reached: The number of full-time administrators outstripped the number of faculty. The trend has accelerated. Many administrators have minimal qualifications and even less general culture, but have increasingly been usurping powers that belonged to the faculty.

Administrators are paid well, and their salaries have helped drive rises in tuition. Between 1981 and 2011, tuition at private colleges tripled (adjusting for inflation), while tuition at public universities quadrupled. In 2010, student loans overtook credit cards as the largest category of personal debt. Many economists think the half-trillion-dollar-a-year higher education industry is coming to resemble a financial bubble.

Fewer opinions

Mr. Lukianoff notes that for more than 10 years, sociologists have reported that students hesitate to express opinions. Unlearning Liberty suggests why. The author explains that students themselves have no idea they have the right to express unpopular views, and that in the “overwhelming majority of cases” other students don’t care when speech is squelched.

Students have heard of free speech, but may misinterpret the concept. Students who muzzle others sometimes say they were just exercising their own constitutionally protected freedom of speech!

The disappearance of debate affects the intellectual climate. Without free speech and discussion, students have only prejudices, clung to emotionally but never examined. Few people can defend their positions, so when they are attacked, their only response is anger and hostility.

A student described another consequence: “It’s as though there’s no distinction between the person and the argument, as though to criticize an argument would be injurious to the person.”

Robert Frost famously defined education as “the ability to listen to almost anything without losing your temper or your self-confidence.” In this sense, education has virtually disappeared from American campuses.

American citizens — so long as they are not on college campuses — enjoy greater freedom of speech than the citizens of any other Western country, but failing to exercise this freedom is the first step toward losing it. The author quotes Judge Learned Hand:

A popular belief in the importance of the values inherent in the U.S. Constitution may be more important than the Constitution itself. If citizens are promised certain rights by law but nobody knows they have them — or enough people believe they shouldn’t have them — the law ends up mattering little.